[box type=”bio”] What to Learn from this Article?[/box]

Thoracic spondylodiscitis has a low incidence in the developed world and may pose a diagnostic challenge when atypical symptoms such as chest pain predominate on presentation.

Case Report | Volume 7 | Issue 4 | JOCR July – August 2017 | Page 51-53| Rahul Pankhania, Ashish Narang, Rohi Shah, Shyamsundar Srinivasan. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.848

Authors: Rahul Pankhania[1], Ashish Narang[1], Rohi Shah[1], Shyamsundar Srinivasan[1]

[1] Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Kettering General Hospital, Kettering NN16 8UZ, United Kingdom.

Address of Correspondence

Dr. Rahul Pankhania,

Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Kettering General Hospital, Rothwell Road, Kettering NN16 8UZ, United Kingdom.

E-mail: rahul.pankhania@nhs.net

Abstract

Introduction: The diagnosis of thoracic spondylodiscitis is challenging, given that it is a rare entity in itself and when unusual symptoms such as central chest pain predominate on presentation, it may pose a serious diagnostic challenge.

Case Report: A 54-year-old patient presented to accident and emergency with central chest pain and elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein [CRP]: 21 mg/L). Following exclusion of life-threatening cardiac causes, he was discharged home with analgesia and no formal diagnosis. Over the course of the subsequent 6 weeks, he presented to his general practitioner on two different dates with worsening chest pain alongside a new symptom of back pain and progressively rising inflammatory markers. At 6 weeks, he presented back to the emergency department with clinical signs of sepsis, mid-thoracic tenderness with weakness and altered sensation to his legs. The CRP was raised at 297 mg/L. In view of these symptoms, a contrast magnetic resonance imaging scan was performed which revealed destruction of the sixth and seventh disc space with high signal intensity on T2 and short tau inversion recovery images in T6 and T7. Blood cultures were shown to have grown Staphylococcus aureus, and the patient was subsequently treated with combined intravenous antibiotics (flucloxacillin) and oral antibiotics (rifampicin) for 15 weeks resulting in complete resolution of his symptoms.

Conclusion: Our case report highlights the need for a high index of suspicion of spondylodiscitis in patients presenting with central chest pain, unresolving back pain and elevated inflammatory markers especially in the absence of any other formal diagnosis.

Keywords: Central chest pain, thoracic spondylodiscitis, T6-7 nerve root compression.

Introduction

In the UK, 5% of visits to the emergency department are due to chest pain, of which up to 40% require hospital admission for further investigations and management [1]. There are a vast array of illnesses that can present with chest pain however, the majority of these cases are non-cardiac including gastrointestinal, musculoskeletal, psychological, malignant, and pulmonary diseases [2, 3]. In an acute setting, life-threatening causes of cardiac chest pain should always be investigated as a priority. Occasionally no underlying cause is elicited [4], and other potentially rare causes of chest pain should be considered. Thoracic spondylodiscitis has a low incidence and does not usually present with chest pain, which makes it difficult to diagnose and result in substantial consequences if missed. We describe a case report of a 54-year-old patient presenting with central chest pain and a subsequent delayed diagnosis of thoracic spondylodiscitis.

Case Report

A 54-year-old previous fit and well male patient was brought to the emergency department with a 2-h history of central chest pain. He was immediately transferred to the coronary care unit and had a series of investigations including routine blood tests with cardiac enzymes and serial cardiac enzymes. Blood tests on admission revealed a normal full blood count, renal function and normal cardiac markers (troponin T: <10 ng/L) on initial and on 12-h repeat blood test. The C-reactive protein (CRP) was noted to be mildly elevated at 21 mg/L. The patient’s pain eased with analgesics, and he was subsequently discharged home with no formal diagnosis. Over the next few days, the patient continued to experience intermittent episodes of chest and back pain with radiation of symptoms to his shoulder and arms. He visited his local general practice doctor on two separate occasions at 3 days and 3 weeks following his initial admission. Cardiac causes of chest pain were once again excluded, however, a gradual rise in his CRP was noted of 52 mg/L at 3 days and 68 mg/L at 3 weeks. A chest X-ray was done at 3 weeks and reported normal.

Nearly, 6 weeks following his initial presentation, he presented back to the emergency department with clinical signs of sepsis including pyrexia with a temperature of 38.4°C, tachycardia (heart rate: 109 bpm) and now with severe back pain and worsening central chest pain. On examination, the patient was unable to stand up straight due to the severity of his back pain. He had a diffuse spinal tenderness with localized tenderness in the mid-thoracic level as well as the upper lumbar spine. Lower limb examination revealed weakness in his right hip secondary to pain inhibition with nondermatomal altered sensation to his right leg. He had a positive straight leg raise at 30° on right side. Both knee and ankle reflexes were normal bilaterally with no evidence of clonus and Babinski reflex was normal. Per-rectal examination revealed normal perianal sensation with a normal resting anal tone. Blood markers revealed a CRP of 297 mg/L and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) of 77 mm/h. The white cell count was noted to be 7.9 × 103/µL with a neutrophil count of 5.1 × 103/µL. A full septic screen was performed including blood and urine cultures, and the patient was started on broad spectrum antibiotics – tazocin (piperacillin and tazobactam) to treat for sepsis of unknown origin. Plain X-rays of the chest, hips and spine were also conducted revealing no gross abnormality.

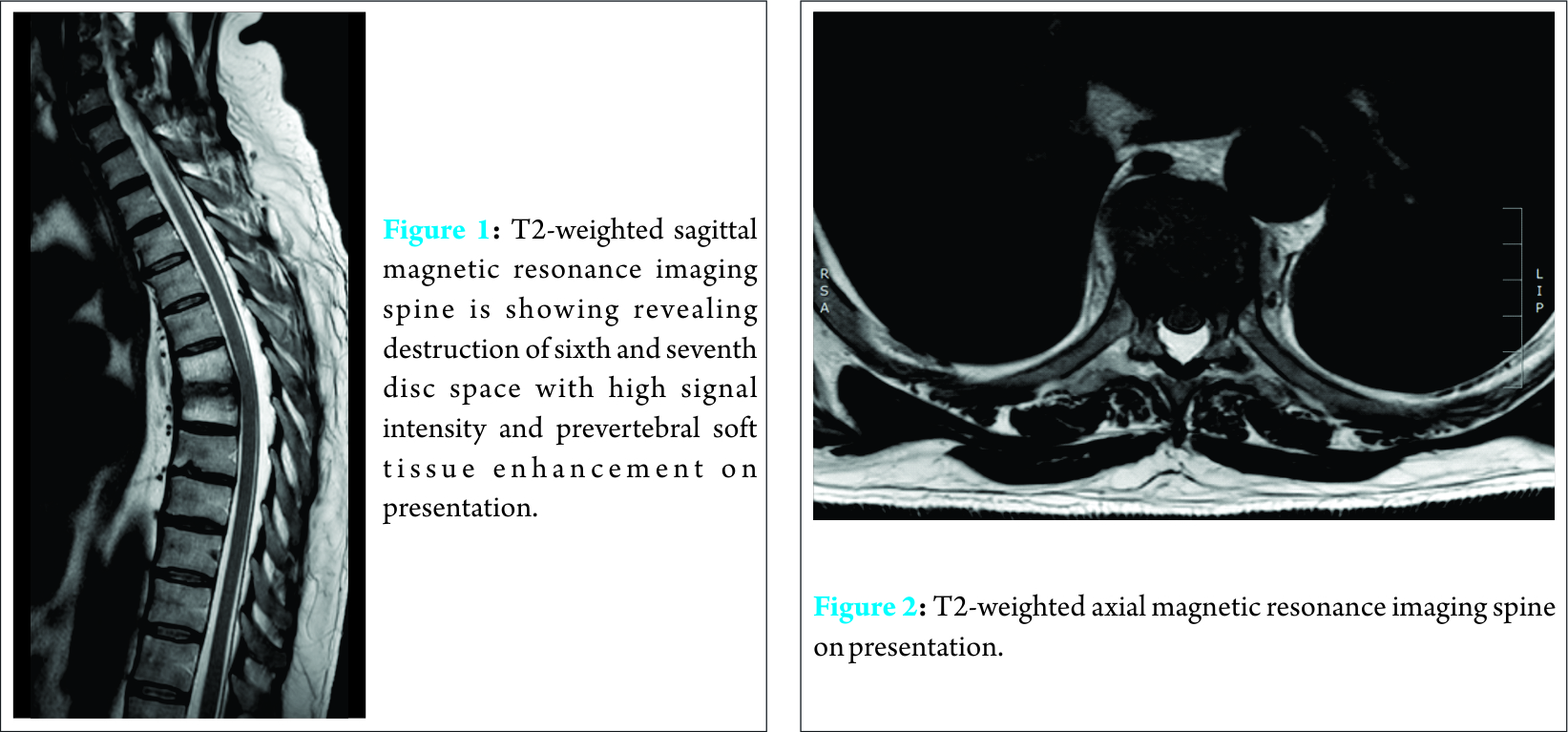

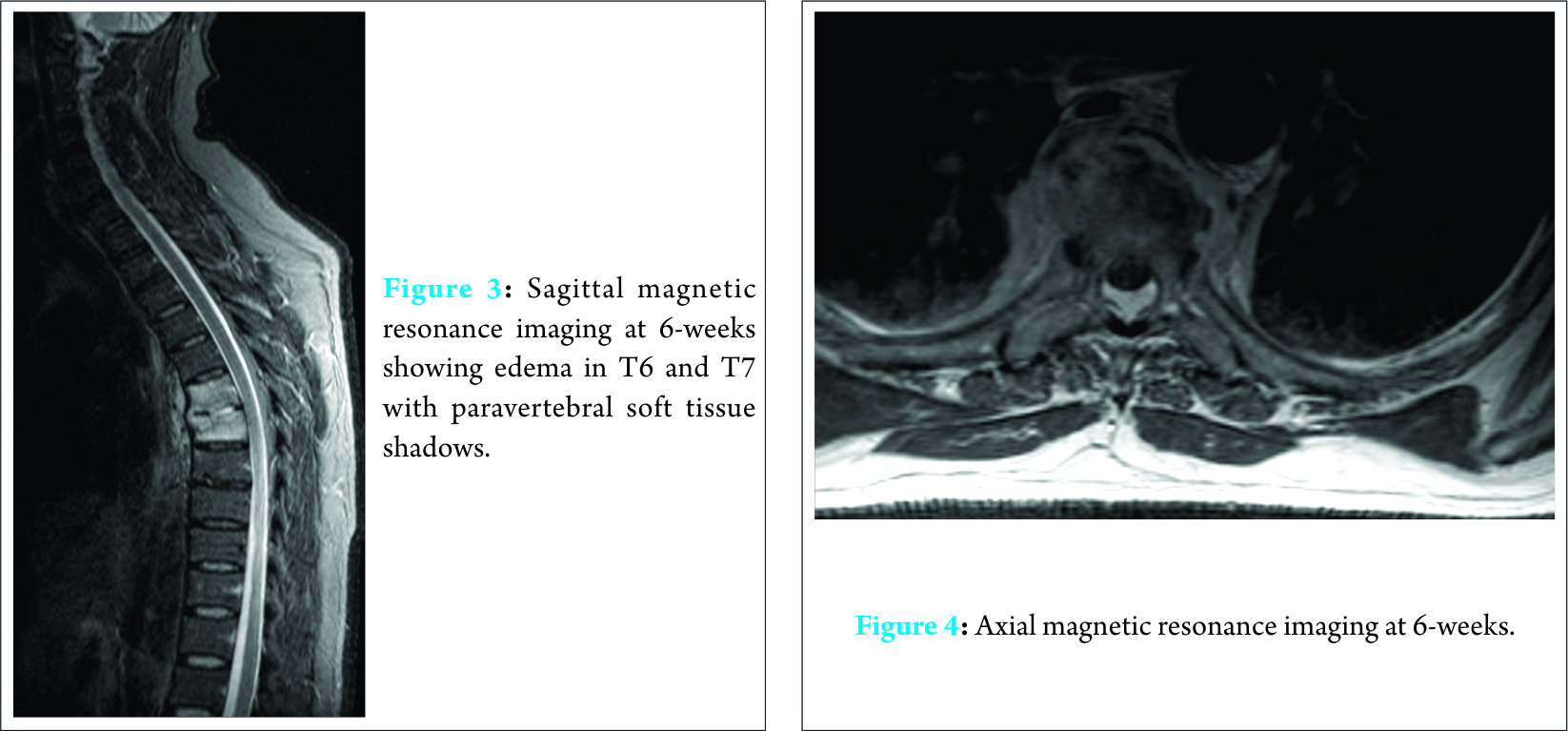

In view of the now localized thoracic spinal tenderness, a contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the whole spine was arranged. This revealed destruction of the sixth and seventh disc space with high signal intensity on T2 and short tau inversion recovery images in T6 and T7. There was a prevertebral soft tissue enhancement anterior to these vertebrae but no cord compression (Fig. 1 and 2). There was an annular tear at the L4/5 disc, which may have accounted for the lumbar pain. A computed tomography thorax, abdomen and pelvis did not reveal any other septic foci. Blood cultures grew Staphylococcus aureus. The patient was immediately commenced on an appropriate antibiotic regime (intravenous flucloxacillin and oral rifampicin) following advice from the microbiology team. He responded well to the treatment with improvement his thoracic spinal pain and complete resolution of the weakness and altered sensation to his right leg. Within 5 days of commencing the antibiotic regime, his CRP dropped to 36 mg/L. A 6-week repeat contrast MRI at 6 weeks still showed edema in T6 and T7 with paravertebral soft tissue shadows (Fig. 3 and 4). After 15 weeks of treatment, his pain had completely resolved, and his CRP and ESR levels were within normal limits. His antibiotic regime was subsequently stopped, and the patient continued to be symptom-free at 5 months from his initial presentation.

Discussion

Pyogenic infection of the intervertebral discs and adjacent vertebrae often referred to as spondylodiscitis or vertebral osteomyelitis is relatively rare accounting for up to 2-7% of all skeletal infection [5, 6, 7]. Spondylodiscitis is most prevalent in adults over 50 years of age, with a male to female ratio of 5:1. Incidence increases with age for each successive decade of life. The lumbar spine is most commonly affected (58%) followed by the cervical spine (30%) and the thoracic spine (11%) [8]. Hematogenous spread is the most common cause of pyogenic spondylodiscitis usually from the genitourinary tract, respiratory tract or other soft tissues causing a bacteremia. However, is it is often difficult to find a primary site of infection, with up to 37% of cases not having a determinate source [9]. Understanding the vascular supply for the spine explains the mechanism behind the spread of infection. In adults, the intervertebral discs are avascular, and end arteries are created due to involution of the intraosseous anastomoses. Bacteremia from another site can cause small septic emboli to lodge in the end arterioles and proliferate, causing bone infarction and osteomyelitis. Rupturing of the emboli causes infection to spread through the end plate and into the disc itself [10]. This can extend from the vertebral bodies to the epidural space creating an epidural abscess. The spread of infection is a good determinant in assessing the origin of the infection [9, 10]. Post-operative and iatrogenic spondylodiscitis have direct involvement of the disc space usually due to direct inoculation, while spontaneous spondylodiscitis originates in the vertebral body and then spreads to the disc space. MRI scanning remains the preferred imaging modality with a high sensitivity and specificity [11, 12]. Microbiological cultures are essential in the diagnosis to target treatment. Blood tests typically give a picture of elevated ESR and CRP in 90% of pyogenic spondylodiscitis [13]. The most common causative organism of spondylodiscitis in the western world is the Staphylococcus species (S. aureus) 50-65%, followed by Streptococcus, Enterococcus, Pseudomonas, and Escherichia coli species [14]. Identifying the causative organism through culture although necessary is a time intensive process, during which neuropathy could already have progressed. This emphasizes the need for a comprehensive history and thorough examination to delineate a cause and identify predisposing factors (e.g., immunosuppression, diabetes, substance misuse, long-term steroid use, and travel to high-risk destinations). The presentation of spondylodiscitis is non-specific, making treatment and diagnosis even more difficult to determine. Medical management may be considered when there is minimal bone destruction present, clinical symptoms are mild, and there is no neurological deficit or when the risks of surgical intervention outweigh the benefit [15]. Antimicrobial treatment should not be started until a specific pathogen is identified unless a patient is neutropenic or in severe sepsis. In this case, the patient should be started on empirical broad-spectrum antibiotics, based on what organism is most likely. If initial culturing is negative, a percutaneous biopsy of the affected discs should be obtained and blood cultures routinely taken. Once a specific pathogen has been identified, antibiotics specific to the pathogen should be administered parent rally. There is no specific guidance on the duration of treatment, however, studies have shown a higher relapse rate when treatment was stopped earlier than 4 weeks [16, 17]. Emergency surgical intervention in patients is advocated when sepsis or neurological deficits occur. Other indications for surgery include debridement and removal of the septic tissue, collection of specimens for microbial cultures, decompression of the spinal canal, stabilization and realignment of the infected segment and spinal fusion. Our patient presented with isolated central chest pain marginally elevated inflammatory markers and no signs of systemic sepsis, an atypical first presentation with no formal diagnosis obtained. This gradually progressed to back pain and localized tenderness with progression of the infection leading to readmission with severe sepsis. We suspect that the symptom of central chest pain was caused by nerve root compression at T6-T7 level, which improved with subsequent treatment.

Conclusion

The diagnosis of thoracic spondylodiscitis is challenging given that it is a relatively rare entity in itself, and when unusual symptoms such as central chest pain predominate on presentation, it may pose a complex diagnostic challenge. This case report highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for discitis in patients presenting with chest pain, back pain, and rising inflammatory markers, especially in the absence of any other formal diagnosis.

Clinical Message

Although an unusual presentation, thoracic spondylodiscitis may present with central chest pain due to irritation/compression of the thoracic nerve root. The most common causative organism of spondylodiscitis in the western world is the Staphylococcus species – S. aureus (50-65%). Treatment in the form of medical management may be considered when there is minimal bone destruction present, clinical symptoms are mild or when the risks of surgical intervention outweigh the benefit. Surgical intervention is recommended in septic patients or patients with neurological deficits. This may include removal of septic tissue, a collection of specimens for microbial cultures, decompression of the spinal canal, spinal fusion and stabilization, and realignment of the infected segment.

References

1. Ruigómez A, Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Jones R. Chest pain in general practice: Incidence, comorbidity and mortality. Fam Pract 2006;23(2):167-174.1. Ruigómez A, Rodríguez LA, Wallander MA, Johansson S, Jones R. Chest pain in general practice: Incidence, comorbidity and mortality. Fam Pract 2006;23(2):167-174.

2. Wong WM, Lam KF, Cheng C, Hui WM, Xia HH, Lai KC, et al. Population based study of non-cardiac chest pain in southern Chinese: Prevalence, psychosocial factors and health care utilization. World J Gastroenterol 2004;10:707-712.

3. Eslick GD, Jones MP, Talley NJ. Non-cardiac chest pain: Prevalence, risk factors, impact and consulting – A population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2003;17(9):1115-1124.

4. Ockene IS, Shay MJ, Alpert JS, Weiner BH, Dalen JE. Unexplained chest pain in patients with normal coronary arteriograms: A follow-up study of functional status. N Engl J Med 1980;303(22):1249-1252.

5. Digby JM, Kersley JB. Pyogenic non-tuberculous spinal infection: An analysis of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1979;61(1):47-55.

6. Krogsgaard MR, Wagn P, Bengtsson J. Epidemiology of acute vertebral osteomyelitis in Denmark: 137 cases in Denmark 1978-1982, compared to cases reported to the national patient register 1991-1993. Acta Orthop Scand 1998;69(5):513-517.

7. Beronius M, Bergman B, Andersson R. Vertebral osteomyelitis in Goteborg, Sweden: A retrospective study of patients during 1990-1995. Scand J Infect Dis 2001;33(7):527-532.

8. Mylona E, Samarkos M, Kakalou E, Fanourgiakis P, Skoutelis A. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: A systematic review of clinical characteristics. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2009;39(1):10-17.

9. Lestini WF, Bell GR. Spinal infections: Patient evaluation. Semin Spine Surg 1991;2:244-256.

10. Govender S. Spinal infections. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87(11):1454-1458.

11. Carragee EJ. The clinical use of magnetic resonance imaging in pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22(7):780-785.

12. Dunbar JA, Sandoe JA, Rao AS, Crimmins DW, Baig W, Rankine JJ. The MRI appearances of early vertebral osteomyelitis and discitis. Clin Radiol 2010;65(12):974-981.

13. Nather A, David V, Hee HT, Thambiah J. Pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis: A review of 14 cases. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2005;13(13):240-244.

14. Hadjipavlou AG, Mader JT, Necessary JT, Muffoletto AJ. Hematogenous pyogenic spinal infections and their surgical management. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25(13):1668-1679.

15. Sobottke R, Seifert H, Fätkenheuer G, Schmidt M, Gossmann A, Eysel P. Current diagnosis and treatment of spondylodiscitis. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2008;105(10):181-187.

16. Nolla JM, Ariza J, Gómez-Vaquero C, Fiter J, Bermejo J, Valverde J, et al. Spontaneous pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis in nondrug users. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002;31(4):271-278.

17. Osenbach RK, Hitchon PW, Menezes AH. Diagnosis and management of pyogenic vertebral osteomyelitis in adults. Surg Neurol 1990;33(4):266-275.

|

|

|

|

| Dr. Rahul Pankhania | Dr. Ashish Narang | Dr. Rohi Shah | Dr. Shyamsundar Srinivasan |

| How to Cite This Article: Pankhania R, Narang A, Shah R, Srinivasan S. Central Chest Pain – An Atypical First Presentation. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2017 Jul-Aug;7(4):51-53 |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com