Mild ankle pain and swelling cases should be evaluated properly with high degree of suspicion for early detection of the tumor and curettage with bone cementing gives good functional outcome leading to preservation of ankle and subtalar joints.

Dr. Rajesh Rana, Department of Orthopaedics, Institute of Medical Sciences SUM Hospital and Medical College, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: rajesh.rana66@gmail.com

Introduction: A giant cell tumor (GCT) is a benign tumor of bones which commonly arises from epiphysis of long bones. The tumor is locally aggressive and rarely metastasizes to the lungs. GCT of small bones of the foot and ankle is very rare. The GCT of the talus is very rare, and only a few case reports and series are described in the literature. In general, the GCT is monostotic, and few incidences of multicentricity have been described in the foot and ankle bones literature. Here are the findings of our case GCT of talus and reviews of earlier literature.

Case Report:We present a case of a GCT of the talus in a 22-year-old female. Patient presented with pain in ankle with mild swelling and tenderness at ankle. Radiograph and Computer tomography scan conformed an eccentric osteolytic lesion on anterolateral part of talus body. Magnetic resonance imaging showed no extra osseous extension or articular surface breach. Biopsy conformed the lesion to be giant cell tumor. The tumor was reated with curettage and bone cement filling.

Conclusion: Giant cell tumor of talus is extremely rare and presentation of these tumor may change. Curettage and bone cementing are an effective method of treatment. It gives early weight bearing and rehabilitation.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, talus, osteolytic lesion, curettage, Giant cell tumor of small bones.

A giant cell tumor (GCT) is a benign bone tumor that most commonly arises from long bones’ epiphysis. GCT from the ankle and foot is very rare, with an incidence of around 1–2% [1]. Only a few case reports and series exist in the literature on foot and ankle GCTs. Some reports say, it occurs in the younger age group and is multicentric [2]. The generalized consensus regarding foot and ankle GCT is still to be concluded because of the tumour’s rarity. Here, we present a case of a GCT arising from talus in a 22-year-old female patient.

A 22-year female came to the hospital with a chief complaint of pain in her left ankle for the last 6 months. The pain was of insidious onset and non-radiating localized type and was aggravated with activities. The pain persisted throughout the day. The patient had complained of mild swelling at the ankle. There was no history of trauma, fever, weight loss, or similar episode in the past. The family and personal history were normal. Systemic and general examinations were within normal limits and ruled out any other place occurrence.

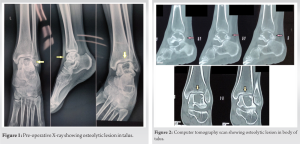

On examination of the ankle, the joint had mild swelling and joint line mild tenderness was there. The range of movements was terminally restricted. There was no visible sinus, venous engorgement, or skin changes. All the blood parameters were within normal limits. The ankle radiograph was taken with AP, lateral, and Mortis views. The radiograph showed an eccentric osteolytic lesion in the talus (Fig. 1). The lesion was on the anterolateral aspect of the talar body. There was no cortical breach, and ankle, and subtalar joint spaces were well maintained. Computer tomography scan of the ankle also confirmed there was no cortical breach (Fig. 2).  There was thinned cortex and osteolytic lesion in the anterolateral aspect of the talar body. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ankle was done. MRI showed an expansile destructive lesion in the talus body with a sclerotic margin and multiple locules (Fig. 3). The lesion showed small solid enhancing areas with the hemorrhagic fluid component. There was no cortical break or intra-articular extension. There was no peritalar soft-tissue extension. The MRI had a suggestive diagnosis of a GCT with secondary ABC. The routine blood investigations were within normal limits, including hemogram, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Chest radiograph ruled out pulmonary metastasis. The tumour was a campanaci Grade 1 type with a well-marginated border and intact cortex.

There was thinned cortex and osteolytic lesion in the anterolateral aspect of the talar body. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the ankle was done. MRI showed an expansile destructive lesion in the talus body with a sclerotic margin and multiple locules (Fig. 3). The lesion showed small solid enhancing areas with the hemorrhagic fluid component. There was no cortical break or intra-articular extension. There was no peritalar soft-tissue extension. The MRI had a suggestive diagnosis of a GCT with secondary ABC. The routine blood investigations were within normal limits, including hemogram, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein. Chest radiograph ruled out pulmonary metastasis. The tumour was a campanaci Grade 1 type with a well-marginated border and intact cortex.

The patient went fluoroscopy-guided core needle biopsy through the anterolateral side of the talus. Histopathological examination showed multinucleated giant cells in the background of mononuclear stromal cells. Biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of a GCT. Curettage and bone cementing were planned through an anterolateral approach as the lesion was on the anterolateral part of the body of the talus. The incision was on the anterolateral aspect of the ankle and foot extending from the talus toward the fourth metatarsal. On deepening the incision extensor digitorum brevis muscle is exposed. The muscle was split to access the anterolateral part of the body and the neck of the talus. A large window was made on the cortex of talus anterolaterally.

The tumor tissue was curated out from the lesion. Then high-speed burr was used to enlarge the cavity and remove the rest of the tumor tissues from the corners (Fig. 4). Curettage was done till normal bone was visible with punctate bleeding. We washed the cavity with a copious amount of normal saline to remove all the tumor debris. We washed again with hydrogen peroxide saline solution. The walls were spray cauterized to kill all the residual tumor cells. We cleaned all the corners and crevices with the above three steps: Curettage, burring, and electrocauterization. All the corners were checked for residual tissue and fluoroscopy was used to confirm all locations – the void formed after the curettage was filled with Polymethyl methacrylate bone cement (Fig. 5). The wound was closed in layers and a slab was given below the knee. The patient was kept non-weight bearing for 21 days and weight-bearing was allowed. The patient was kept non-weight bearing for 21 days and weight-bearing was allowed. For the first 3 months, the patient was followed up monthly and then at quarterly intervals for 1 year. For the next year, she was followed up every 6 months. There was no clinical and radiological evidence of recurrence.

A GCT is a common benign and locally aggressive tumor of bone but sometimes, it metastases to the lungs [3]. Only a few cases have been reported in the literature on GCT in the talus. Around 28 cases have been reported in the talus till now. Hence, GCT of the talus is an extremely rare condition.

GCT is a eccentrically expanding locally aggressive benign tumor. Most of the case reports showed osteolytic lesions of the talus with preserved ankle and subtalar joints [4]. Few cases showed effusion in the joints. In our case, we found a similar finding of no intra-articular breach and joint spaces were well maintained.

The standard modality treatment of such contained type GCT s is curettage and filling the defect with bone cement or bone grafts [5]. The entire cavity is scooped out in curettage and washed with a copious amount of normal saline. Then, high-speed burr is used to remove all the bone tumor cells and enlarge the cavity uniformly. In extended curettage, chemicals such as phenol, liquid nitrogen, or radiofrequency are used after curettage [6]. In our case, we did curettage and filled with PMMA bone cement. Bone cement gives immediate structural support and allows early weight bearing [7]. The heat produced while the setting of cement helps in killing the residual tumor cells by themotoxic effect [8]. Bone cement filling helps to detect any recurrence early [9]. In the case of filling with bone grafts, weight bearing is delayed and recurrence cannot be detected early. Cement has some adverse effects such as thermal necrosis and long-term degenerative changes in the adjacent joint [10]. If extensive involvement of the talus occurs, than partial or complete talectomies are the options. After resection, tibiotalar or tibial calcaneal fusions are the preferred modalities of treatment [11]. Giant cell tumor is a benign condition with favorable prognosis but in 5% of cases, it metastasizes to lungs [12]. Fortunately, in our case, there was no metastasis. GCT is a locally aggressive tumor and up to 20% chance of recurrence is there [13]. When surgery cannot be done than radiotherapy and denosumab treatment are given [14]. Radiation increases risk of malignant transformation in GCT [15].

The GCT arising from talus usually presents with pain and swelling at ankle area. We had also similar presentation for our case. Sometimes, GCT can present as pathological fracture. Plane radiograph helps in early detection of such lesions. GCT talus sometimes presents as multicentric lesion such as other small bone GCT [2]. Other area of body should be carefully screened to rule out multicentricity.

Prognosis after intralesional curratage is good. The patient has to be followed up to detect any recurrence or metastasis of lungs. The radiograph of the local site and lungs is taken at regular interval till 2 years. In our case, we did not find any recurrence or metastasis on 2 years of follow-up. The patient has well maintained joint space and no pain.

The high degree of suspicion of mild ankle pain cases can lead to early diagnosis of rare GCT of talus. Routine imaging such as radiograph, MRI, and biopsy helps in conformation of the diagnosis. Curettage and bone cement give good functional outcome.

GCT of talus is extremely rare. Mild ankle pain and swelling cases should be evaluated properly for early detection of the tumor. Early intervention with curettage and bone cementing gives good functional outcome. It helps in preservation of both ankle and subtalar joint.

References

- 1.Rhee JH, Lewis RB, Murphey MD. Primary osseous tumors of the foot and ankle. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2008;16:71-91. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dhillon M, Prasad AP, Virk M, Aggarwal S. Multicentric giant cell tumor involving the same foot: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:154-7. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murshed KA, Elsayed AM, Szabados L, Rashid S, Ammar A. Locally aggressive giant cell tumor of bone with pulmonary distant metastasis and extrapulmonary seeding in pregnancy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 2020;4:e19.00161. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Galvan D, Mullins C, Dudrey E, Kafchinski L, Laks S. Giant cell tumor of the talus: A case report. Radiol Case Rep 2020;15:825-31. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Puri A, Agarwal M. Treatment of giant cell tumor of bone: Current concepts. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:101. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang Y, Tian Q, Wu C, Li H, Li J, Feng Y. Management of the cavity after removal of giant cell tumor of the bone. Front Surg 2021;8:626272. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pulatkan A, Uçan V, Tokdemir S, Elmali N, Gürkan V. Use of cement combined grafting in upper and lower extremity benign bone tumors. Jt Dis Relat Surg 2020;31:335-40. [Google Scholar]

- 8.He H, Zeng H, Luo W, Liu Y, Zhang C, Liu Q. Surgical treatment options for giant cell tumors of bone around the knee joint: Extended curettage or segmental resection? Front Oncol 2019;9:946. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu X, Xu M, Xu S, Su Q. Clinical outcomes of giant cell tumor of bone treated with bone cement filling and internal fixation, and oral bisphosphonates. Oncol Lett 2013;5:447-51. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mavrogenis AF, Igoumenou VG, Megaloikonomos PD, Panagopoulos GN, Papagelopoulos PJ, Soucacos PN. Giant cell tumor of bone revisited. SICOT J 2017;3:54. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar BU, Sharma PR, Ram GS, Kumar PV. Aggressive giant cell tumour of talus with pulmonary metastasis-a rare presentation. J Clin Diagn Res 2014;8:LD01-3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hosseinzadeh S, De Jesus O. Giant Cell Tumor. Diagnosis Musculoskelet Tumors Tumor-like Cond Clin Radiol Histol Correl-Rizzoli Case Arch; 2022. p. 101-5. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559229. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palmerini E, Picci P, Reichardt P, Downey G. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone: A review of the literature. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2019;18:1533033819840000. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu SF, Adams B, Yu XC, Xu M. Denosumab and giant cell tumour of bone-a review and future management considerations. Curr Oncol 2013;20:e442-7. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Movahedinia S, Shooshtarizadeh T, Mostafavi H. Secondary malignant transformation of giant cell tumor of bone: Is it a fate? Iran J Pathol 2019;14:165-74. [Google Scholar]