High clinical and radiological suspicion with detailed evaluation is necessary to diagnose ischial tuberosity tuberculosis.

Dr. Sagar Saxena, Department of Orthopaedics, Guru Gobind Singh Government Hospital, Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi, Raghubir Nagar, New Delhi - 110 027, India. E-mail: drsagar.saxena@gmail.com

Introduction: Ischium is one of the rare sites to be involved by mycobacterium tuberculosis. The incidence is generally not more than 0.2% in any of the large series. We report an unusual case of extrapulmonary tuberculosis of the ischial tuberosity presenting with chronic gluteal pain of 6 months duration.

Case Report: A 35-year-old male patient presented with chronic dull aching gluteal pain of 6 months duration, for which lifestyle modifications and rest were advised initially. Antituberculosis chemotherapy was administered (for a period of 1 year) following histopathological confirmation of tuberculosis. At 1 year post antitubercular therapy, the patient had no pain and was symptom free. Furthermore, radiographs showed healed right ischial tuberosity osteomyelitis.

Conclusion: Tuberculosis involving the ischial tuberosity is rare. The early diagnosis is mandatory for good results, and with a worldwide resurgence of the disease, a high index of suspicion is necessary. Prompt diagnosis and treatment resulted in a good clinical outcome in this patient.

Keywords: Ischial tuberosity, tuberculosis, antitubercular chemotherapy.

Musculoskeletal tuberculosis constitutes 1–5% of all tuberculosis cases [1]. Although tuberculosis is a rare infection in the developed world, in the developing world, it is still prevalent. There has been an increased incidence of osteoarticular tuberculosis in association with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) with multiple site involvement. The lack of awareness of the potential extrapulmonary involvement of tuberculosis leads to delay in diagnosis and treatment. Antituberculous drugs should be started after histopathological confirmation and continued for 12–18 months, due to poor drug penetration into osseous and fibrous tissues. We report a case of an unusual location of tuberculosis involving the ischial tuberosity that presented with chronic gluteal pain.

A 35-year-old male presented at our outpatient department with the right buttock pain. He had a dull aching pain in the right buttock for the past 6 months which had increased in intensity over the previous 2 months. The pain had worsened while sitting, especially on a hard surface and was not associated with swelling. Since 6 months, he had been taking oral analgesics to control the pain and was partially relieved. He complained of low-grade fever on and off with insignificant loss of weight and normal appetite but had disturbed sleep. He had no previous history of contact with tuberculosis in or outside the family. A physical examination conducted at presentation revealed skin over the right buttock was non-inflamed and tender on deep palpation, but there was no sinus. Range of motion of the right hip was painful in flexion beyond 70° and terminal internal rotation. No inguinal lymphadenopathy was detected. Sacroiliac joints, lumbosacral spine, and knees were within normal limits.

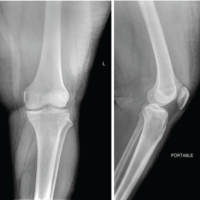

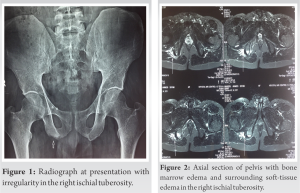

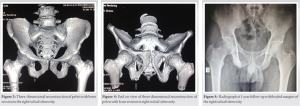

Laboratory investigations revealed hemoglobin of 9.2 g/dl, total leucocyte count of 10,800/mm3 with lymphocytes predominance, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) were 62 mm/hour Westergren, and C-reactive proteins (CRP) levels were 2.6 mg/dl (both elevated). Mantoux test had an induration of 24 mm, and the chest radiograph was clear. A plain radiograph of the pelvis revealed an osteolytic lesion over the right ischial tuberosity clearly distinguishable from the opposite side (Fig. 1). However, computed tomography (CT) (Fig. 2, 3, 4) imaging showed irregularity and destruction of the right ischial tuberosity with associated soft-tissue thickening and fat stranding. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed involvement of the right ischial tuberosity with changes in signal intensity without any collection.

Diagnostic confirmation was done by histopathological examination of the tissue obtained by CT-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology from the lesion which showed epithelioid granuloma. However, mycobacteria could not be cultured.

The patient was started on a 12-months course of a four-drug antitubercular chemotherapy regimen which included 2 months of intensive phase and 10 months of continuation phase, comprising Isoniazid (5 mg/kg), Rifampicin(10 mg/kg), Pyrazinamide (25 mg/kg), and Ethambutol (15 mg/kg), along with rest and lifestyle modifications. During the course of treatment, range of motion of the right hip became pain free in both full flexion and terminal internal rotation. At the time of last follow-up, the patient had no pain on sitting and had returned to his normal activities. Plain radiograph revealed consolidation of the osteolytic lesion of the right ischial tuberosity (Fig. 5), and laboratory parameters (ESR and CRP) were also normalized.

Tuberculous infection of the ischium is a rare condition. Magnusson (1938) in an article, in which he estimated the incidence of ischial tuberosity tuberculosis to be 0–2% of all cases of bone tuberculosis [2]. Osteoarticular tuberculosis presenting at unusual sites like the ischium may be even more difficult to diagnose and can present to the hospital very late [3]. This can lead to increasing damage even to the extent that acetabulum can get involved theoretically risking the hip joint [4]. Mode of spread of osteoarticular tuberculosis is generally hematogenous from a primary site.

Between the years 1901 and 1935, only seven cases were reported in the literature (all in French) and in 1936 Kaplan described the first case in English literature [2]. In 1973, Bhattacharyya reported three cases of ischial tuberosity tuberculosis and all cases were treated by thorough curettage and antituberculosis treatment (with good clinical outcome) [5]. Silva (1980) showed only one case of ischial tuberosity tuberculosis out of 219 cases of osteoarticular tuberculosis [6]. In 1985, Samar et al. reported paratracheal lymphadenopathy with ischial tuberculosis in a 6-year-old boy [7]. In 2010, Krishnan et al. reported a case of ischial tuberosity tuberculosis presented with chronic gluteal abscess treated with incision and drainage, curettage, and antitubercular chemotherapy (with good clinical outcome) [3]. More recently, in 2016, Dhillon et al. reported a case of bilateral ischial tuberculosis treated with antitubercular chemotherapy for 18 months with good clinical outcome [4].

The most common mode of presentation of ischial tuberculosis is pain with multiple sinuses or fistulas [8]. Ischium does not form part of any joint, but as it bears weight while sitting, it is prone to direct pressure causing pain. Therefore once involved, pathology is detected at the earliest [4]. Our patient was not able to sit due to pain.

At the early stage of infection before the formation of a cold abscess or sinuses, the disease can be suspected only by MRI or CT scan [9]. Polymerase chain reaction is a highly sensitive modality of detecting mycobacterial infections but with care, the test sample is representative of the lesion and should be adequately collected and processed [4]. Minimally invasive procedures such as CT-guided aspirations prove to be very handy, whenever clinical and radiological suspicion exists apart from laboratory tests which only play a supportive role. In the past few years, there has been an increased incidence of osteoarticular tuberculosis in association with Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome in developing countries [3]. HIV is the leading risk factor for reactivation of latent disease [10]. Our case was investigated for HIV and was non-reactive. The treatment of osteoarticular tuberculosis is primarily medical [11]. Surgical treatment is reserved for cases, where diagnosis is in doubt, inadequate results of therapy, presence of large abscesses, and recrudescent disease in spite of treatment [12]. Kwon et al. reported a case of ischial tuberculosis that recurred after 8 years which was initially treated with surgery. The lesion settled only after a combined antitubercular therapy, along with surgical debridement [13].

Ischium is one of the rare sites to be involved by mycobacterium tuberculosis. Awareness of the disease, clinical, and radiological suspicion helps detect cases on presentation even without classical findings. Hence, early diagnosis and treatment is the key to optimum functional outcome.

Diagnosing tuberculosis of ischial tuberosity can be challenging. Although rare, a high index of suspicion is necessary to diagnose the pathology in this unusual location. A detailed evaluation is essential.

References

- 1.Weir MR, Thornton GF. Extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Experience of a community hospital and review of the literature. Am J Med 1985;79:467-78. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Tupman GS. A case of tuberculosis of the ischium. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1953;35-B:590-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Krishnan H, Park KS, Cho YJ. Ischial tuberosity tuberculosis: An unusual location and presented as chronic gluteal abscess. Malays Orthop J 2010;4:42-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Dhillon MS, Dhatt SS. Bilateral ischial tuberculosis. J Postgrad Med Educ Res 2016;50:197-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Bhattacharyya AN. Tuberculosis of the ischium: A report of three cases. Aust N Z J Surg 1973;42:389-91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Silva JF. A review of patients with skeletal tuberculosis treated at the university hospital, Kuala Lumpur. Int Orthop 1980;4:79-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Samar G, Eghrari M, Saebi E. Tuberculosis of the ischium. Indian J Pediatr 1985;52:321-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Milch H. Injuries and Surgical Diseases of the Ischium. New York: Hoeber-Harper Book; 1958. p. 104-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Tuli S. Tuberculosis of the Skeletal System. 4th ed. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical; 2010. p. 172-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Kox LF, van Leeuwen J, Knijper S, Jansen HM, Kolk AH. PCR assay based on DNA coding for 16S rRNA for detection and identification of mycobacteria in clinical samples. J Clin Microbiol 1995;33:3225-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Watts HG, Lifeso RM. Tuberculosis of bones and joints. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:288-98. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Dhillon MS, Gupta R, Rao KS, Nagi ON. Bilateral sternoclavicular joint tuberculosis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2000;120:363-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Kwon SE JI, Kim DH. Tuberculosis infection of the ischial tuberosity and that recurred after 8 years-a case report. J Korean Hip Soc 2011;23:79-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]