Surgical decision making and outcome.

Dr. S Ahilan, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai-600116, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: ahilans15@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumour or osteoclastoma is benign, locally aggressive tumor with bone destruction and with malignant potential. It accounts for 5% of all primary bone tumor and occurs in skeletally mature individuals in the age group of 30 to 45 with peak incidence in the 3rd decade. GCT is more common in females. It is usually a solitary lesion and typically involves epiphysio-metaphyseal region. Common sites involved are Distal end of Femur, proximal end of Tibia, distal end of Radius, upper end of Humerus, lower end of Tibia and other sites are hand,spine and Pelvis.

Case Report: A 44 year old male presented with the complaints of pain and swelling over the right wrist for the past 3 months. He was diagnosed as bony giant cell tumor of right distal radius for which right distal radius wide excision was done. Ipsilateral proximal fibular autograft of appropriate length was used to reconstruct the defect. The graft united well with reasonable preservation of range of motion of wrist.

Conclusion: Giant cell tumor of distal radius can be managed by wide excision + reconstruction with proximal fibular autograft instead of arthrodesis. Reasonable range of wrist movements can be preserved.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, excisional biopsy, proximal fibular graft, good functional outcome, Asian dynamic compression plate.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is a benign but locally aggressive lesion consisting of osteoclast-like giant cells, fibroblast-like stromal cells, and blood vessels. Patients with GCTs are usually between 30 and 45 years of age with a female predominance. Most GCTs occur after physeal closure in the involved bone. They can cause pain, swelling, and pathologic fracture, and aggressive lesions cause extensive destruction of normal tissue. They occur in the epiphysis of long bone and extend into the metaphysis. GCTs abut the subchondral surface of the adjacent joint. Common sites include the tibial plateau, femoral condyle, distal radius, and humeral head. Plain radiographs demonstrate lucent, eccentric, expansile lesions with thin or fractured the overlying cortex. Rarely, GCTs appear in multiple sites or produce benign lung metastases. When possible, GCTs are treated with thorough intralesional curettage using a high-speed burr followed by cementation or bone grafting. Frequently, adjuvants such as phenol, cryotherapy, or argon beam coagulation are used to extend the zone of treatment. There is a 10–20% risk of local recurrence. In aggressive lesions with extensive bone destruction, resection of the tumor with adjacent joint is necessary followed by reconstruction using either bone graft or metal prosthesis [1].

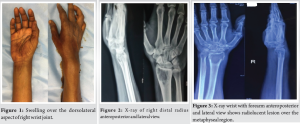

A 44-year-old male presented with complaints of right wrist pain and swelling (Fig. 1) for the past 3 months. He was apparently normal before 3 months. After he developed pain over the right lower forearm which was insidious in onset, non-progressive in nature, dull aching type, non-radiating, aggravated by movements and work relieved by medications. There was no past, family history of note and he was taking no regular medications. On examination of right wrist, diffuse swelling was present just proximal to wrist crease. Tenderness and bony thickening were present over the distal radius.

X-ray of right wrist taken at the time of onset of symptoms – 3 months before presentation (Fig. 2) showed solitary, radiolucent, eccentric lesion over epiphysis and metaphyseal region of right distal radius with narrow zone of transition, with thin cortex. Distal radiocarpal articular surface was maintained. X-ray taken at the time of presentation (Fig. 3) showed the same findings but with additional break in the cortex over medial and lateral aspect of distal radius.

Magnetic resonance imaging of right wrist joint (Fig. 4) shows diffuse aggressive expansile heterogenous lytic lesion with articular extension in the distal end of radius of length 3.8 cm involving the epiphyseal and meta-diaphyseal region with narrow zone of transition with cortical breach in the anterior and posterior aspect of lesion with extraosseous anterior and posterior projections. Initially, core needle biopsy of right distal radius lesion at its proximal margin from the dorsal side was done and diagnosis of GCT of right distal radius was confirmed. After that the patient was planned for definitive management.

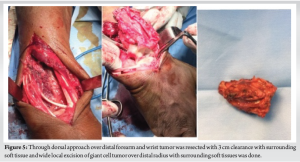

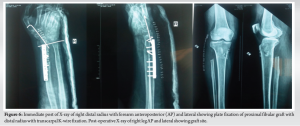

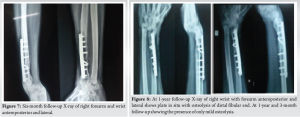

Longitudinal wide excision of right distal radius GCT was planned in view of cortical breach and soft tissue extension. Under general anesthesia, in supine position, incision was made over the dorsal aspect of wrist and forearm. The tumor capsule was identified. Under image intensifier guidance, distal radius was osteotomized. 6.5 cms proximal to distal radius articular surface to give 3 cm of tumor clearance. Using bone holder, the tumor segment with segment of 3 cm of normal bone given for clearance was lifted up (Fig. 5). Care was taken to dissect around the tumor without breaching the tumor. The ligaments of radiocarpal and radioulnar joint were divided and the tumor was delivered out/excised. Proximal fibular autograft including the fibular head was harvested from the ipsilateral right side through the posterolateral approach after isolating the common peroneal nerve. The length of the autograft harvested was around 7 cms. The distal end of this graft was stabilized to the radius with a 3.5 mm Asian dynamic compression plate and screws. Hence, the fibular head resembled and replaced the distal radius. The fibular head was stabilized with two 2 mm Kirschner wires – one fixing it to the carpus and another to the distal ulna (Fig. 6). The patient was maintained on an above elbow slab for 3 weeks and below elbow slab for further 3 weeks. The K-wires and splintage were removed after 6 weeks after which gradual mobilization of wrist and forearm was allowed. The patient was followed up at 3 months, 4 months, 6 months (Fig. 7), and 1 year (Fig. 8) and yearly once after, fibular graft was well united even at 6-month follow-up.

At 2 year and 8 months of follow-up, the patient had (Fig. 9) wrist palmar flexion of 30°, pronation of 70°, supination of 20°, dorsiflexion is NIL. The fibular graft was shorter in comparison to the length of ulna. Probably, if we had taken a longer fibular graft, range of movements may have been better as ulno-carpal impingement could have been avoided. X-ray showed that the fibular graft had well incorporated (Fig. 10).

GCT is a benign aggressive bone tumor of obscure origin presenting in 3rd and 4th decade of life and carries a definite female preponderance [2]. GCTs comprise about 4–5% of primary bone tumors and about 20% of benign bone lesions. After distal femur and proximal tibia, distal radius happens to be the most common site of occurrence for GCT. This site has a further distinction of having more aggressive behavior of GCT with higher chances of recurrences and malignant transformation [3]. The distal radius plays a significant role in the radiocarpal articulation and hence in the function of the hand. It is a challenging factor in the reconstruction of the defect caused by excision of the distal radius tumors. The complexity of the treatment of GCT’s of lower end radius is because of two factors – one is the anatomy and the other is achieving an acceptable functional outcome with clearance of the disease. Various treatment modalities such as extended curettage with or without reconstruction using autogenic/allogenic bone grafts or polymethyl-methacrylate, resection and reconstruction with vascularized or non-vascularized proximal fibula, resection with partial wrist arthrodesis using a strut bone graft, and resection and complete wrist arthrodesis using an intervening strut bone graft are advocated in literature [4].

A lower rate of recurrence has been noted after resection of the distal part of the radius in compared with curettage, especially when the tumor has the cortex or when there has been rapid enlargement of the lesion or a local recurrence. After resection, the defect has been reconstructed as an arthroplasty or an arthrodesis involving use of either vascularized or non-vascularized bone grafts from the tibia, the proximal part of the fibula, the iliac crest, or the distal part of ulna [5]. Although there are advantages to the use of vascularized bone grafts, non-vascularized bone graft was successfully employed in our patient. The advantages of vascularized graft may be less important in the distal radius, due to its relatively short length of resection and graft. Resection with wrist reconstruction by using autogenous proximal fibular grafting without fusion enables the patient to achieve some function at the wrist as compared to fusion. Wide local excision of tumor and reconstruction with ipsilateral proximal fibular autograft allows preservation of movements of the wrist. Patients can return to useful employment despite their functional limitations [6]. Hence, the study used wide excision and autogenous fibular graft as the treatment of choice. There are no signs of recurrence of the tumor till 3 years of follow-up. At 1 year of follow–up, some degree of osteolysis of fibular head was seen which is commonly noted in both free and vascularized proximal fibula autograft. This may be due to loss of vascularity of the fibular head. Our fibular graft was slightly short. The distal end of ulna was impinging on carpus because of which movements were probably restricted. Probably, if we had harvested a longer graft, range of movements of wrist may have been better.

Wide local excision of GCT of distal radius and reconstruction with ipsilateral proximal fibular autograft had found to be effective method of treatment. After a recovery period, patients may achieve a considerably good range of motion and function of the wrist joint with relatively less complications.

This case explains proper diagnosis, pre-operative planning, and meticulous surgical dissection will give good clinical outcome to patient.

References

- 1.Weinstein SL, Buckwalter JA. Turek’s Orthopaedics: Principles and their Application. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Saini R, Bali K, Bachhal V, Mootha AK, Dhillon MS, Gill SS. En bloc excision and autogenous fibular reconstruction for aggressive giant cell tumor of distal radius: A report of 12 cases and review of literature. J Orthop Surg Res 2011;6:14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Mavrogenis AF, Igoumenou VG, Megaloikonomos PD, Panagopoulos GN, Papagelopoulos PJ, Soucacos PN. Giant cell tumor of bone revisited. SICOT J 2017;3:54. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Panchwagh Y, Puri A, Agarwal M, Anchan C, Shah M. Giant cell tumor - distal end radius: Do we know the answer? Indian J Orthop 2007;41:139-45. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Saikia KC, Borgohain M, Bhuyan SK, Goswami S, Bora A, Ahmed F. Resection-reconstruction arthroplasty for giant cell tumor of distal radius. Indian J Orthop 2010;44:327-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Yang YF, Wang JW, Huang P, Xu ZH. Distal radius reconstruction with vascularized proximal fibular autograft after en-bloc resection of recurrent giant cell tumor. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:346. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Agrawal AC, Garg AK, Choudhary R, Verma S, Dash RN. Giant cell tumor of the distal radius: Wide resection, ulna translocation with wrist arthrodesis. Cureus 2021;13:e15034. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Liu YP, Li KH, Sun BH. Which treatment is the best for giant cell tumors of the distal radius? A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:2886-94. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Szendröi M. Giant-cell tumour of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2004;86:5-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;286:241-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]