In complex knee instability cases related to proximal fibula loss a non-anatomic tibial-based posterolateral corner reconstruction should be considered to restore knee stability.

Dr. Vítor Hugo Teixeira Pinheiro, Coimbra Local Health Unit, Coimbra, Portugal. E-mail: pinheiro.vhugo@gmail.com

Introduction: Fibular- and tibiofibular-based reconstructions are the gold standard treatment for posterolateral corner (PLC) injuries of the knee. This is the first report describing a wholly tibial-based PLC reconstruction.

Case Report: A 50-year-old female presented with knee instability following proximal fibular resection for a benign tumor, associated with chronic anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) deficiency from a previous injury. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed fibular collateral ligament (FCL) and distal biceps femoris complete detachment. ACL reconstruction was combined with revision PLC reconstruction, placing the distal grafts, due to lack of fibula, both into the tibia. At 24-month follow-up, the patient reported excellent clinical outcomes.

Conclusion: In cases related to proximal fibula deficiency from resection or congenital causes, a wholly tibial-based PLC reconstruction can effectively restore stability.

Keywords: Proximal fibular resection, knee instability, posterolateral corner reconstruction.

The proximal fibula serves as the insertion point for important stabilizers of the posterolateral corner (PLC), namely, the fibular collateral ligament (FCL), popliteofibular ligament (PFL), fabellofibular ligament, and biceps femoris [1,2]. Therefore, its resection results in an inevitable loss of knee stability, and despite evidence that reattachment of the FCL and biceps femoris to the tibial side of the superior tibio-fibular joint (STFJ) improves functional outcomes [3-5], the rate of symptomatic knee instability after proximal fibula resection is 3.9–16.7% [4-6]. While the long-term effects of proximal fibula resection on knee stability and the development of osteoarthritis have never been reported, varus laxity itself, even when asymptomatic may lead to the development of osteoarthritis [7]. Recent improvement in understanding of the PLC anatomy and its functional interaction with the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) [2, 8-10] has resulted in good outcomes following surgical treatment of combined ACL and PLC injuries [11] Fibular [12,13] and tibiofibular based [8] reconstructions provide effective treatment for PLC injuries, with both having comparable clinical outcomes and restoration of varus and rotational stability [14]. A rare case of knee instability following proximal fibula resection with concomitant ACL deficiency, treated with ACL reconstruction and tibial-based revision PLC reconstruction is presented.

Presentation and diagnosis

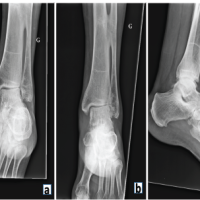

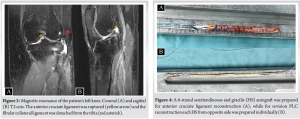

A 50-year-old female nurse presented with left knee instability. Two years prior, she suffered an ACL rupture at work, leading to discovery of an asymptomatic fibular head enchondroma which was confirmed by biopsy. However, as the enchondroma presented with endosteal scalloping, chondrosarcoma could not be excluded, and she underwent proximal fibular resection with FCL and biceps femoris repair with a suture anchor. Two-year post-surgery, she reported gross left knee instability with giving-way episodes, which occurred daily, even with walking. On physical examination, the affected knee had 20° excess hyperextension compared to the contralateral knee, 3+ anterior drawer, negative posterior drawer test, 3+ Lachman, and a 3+ pivot shift. In addition, dial test was symmetric at 30 and 90° flexion (the popliteus tendon was intact, and it is presumed that due to scarring the popliteofibular ligament had function), and 3+ instability to varus stress at 20° flexion and in full extension. This was confirmed with fluoroscopic varus stress views (Fig. 1). Neurovascular examination demonstrated no abnormalities. The affected extremity mechanical alignment was 3.5° varus compared to 1.5° varus on the unaffected limb on full-length standing anteroposterior radiograph. The mechanical lateral distal femoral angle of 88.8° was within normal limits as was the mechanical medial proximal tibial angle of 86.1°. Joint line convergence angle was 2.6°, suggesting that knee joint laxity was partly the cause of varus deformity (Fig. 2). ACL rupture and complete distal detachment of FCL and biceps femoris were confirmed by magnetic resonance imaging. There were no other concurrent ligamentous, meniscal, or chondral lesions (Fig. 3). Left knee ACL reconstruction using ipsilateral semitendinosus and gracilis hamstring (HS) autograft combined with revision PLC reconstruction using contralateral HS autograft was planned. In the absence of the proximal fibula, Pache’s technique was modified to fix both limbs of the graft onto the proximal tibia [15]. It was decided not to undertake an osteotomy as the deformity was <5°, there was no thrust on gait, and in conversation with the patient, she wished to avoid an osteotomy.

Treatment

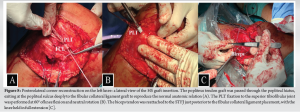

The patient was placed in the supine position, and her knees examined under general anesthesia. A pneumatic tourniquet was applied to each thigh, and standard prepping and draping was carried out. Bilateral semitendinosus and gracilis autografts were harvested. A 6-strand HS graft was prepared for ACL reconstruction (Fig. 4a), while for revision PLC reconstruction, each HS tendon was prepared with non-absorbable whipstitch sutures (Fig .4b). A diagnostic knee arthroscopy was carried out with no other concurrent chondral or meniscal lesions identified. Subsequently, a single anteromedial bundle ACL reconstruction was undertaken with femoral fixation using a fixed-loop device and tibial fixation with an interference screw. Then, a curvilinear lateral skin incision was performed, passing over the lateral epicondyle and Gerdy´s tubercle (Fig. 5a), keeping a skin bridge more than 6 cm from the prior incision. The common peroneal nerve (CPN) was identified, dissected free (Fig. 5b) and protected throughout. The FCL and biceps tendon were found to each have avulsed from the tibia, and a non-absorbable suture was applied to each stump. (Fig. 5c). On the femur, FCL and popliteus tendon (PLT) graft tunnels were drilled as described by Pache et al. (Fig. 6a) [15]. Similarly, for the PLT tibial insertion site preparation, the guide pin was drilled from the tibial “flat spot”, distally and medial to Gerdy’s tubercle, toward the popliteus musculotendinous junction posteriorly (Fig. 6b). In the absence of the fibula head, the distal FCL tunnel was placed at the tibial side of the STFJ (Fig. 7a). At the point of maximum FCL tension in full extension, with slack in flexion (determined by placing a suture across femoral and tibial guide pins and moving the knee through range of motion whilst maintaining neutral axial rotation), a guide pin was placed and drilled from lateral to medial, parallel to the joint line in the coronal plane, 8 mm posterior to the anterior limit, and 25 mm distal to the superior limit of the STFJ, respectively (Fig. 7b). FCL and popliteus tendon (PLT) grafts were fixed on the femur with interference screws. The FCL graft was passed lateral to medial through the tibial tunnel and fixed with the knee at 30° knee flexion in neutral rotation. The PLT graft was passed in a posteroinferior direction through the popliteal hiatus (Fig. 8a) and thence anteriorly through its tibial tunnel and fixed at 60°knee flexion and neutral rotation (Fig. 8b). Finally, both native stumps were reattached to the STFJ with anchors: the native FCL just proximal to the FCL placement at 30° of knee flexion; and the biceps tendon just posterior to the FCL placement, with the knee in full extension (Fig. 8c). The knee was then put through full range of motion and ligament stability confirmed.

A drain was placed in the lateral wound and removed next day. The wounds were closed in layers, and a compressive dressing was applied. Postoperatively, the knee was placed in a hinged knee brace for 6 weeks, locked at 10° flexion for 2 weeks, and flexion was limited to 90° for 2 weeks. Thereafter, the getting the knee straight was prioritized but no hyperextension was encouraged. The brace was removed for icing, exercises, and comfort at rest. The patient was toe-touch weight-bearing for the first 2 weeks, followed by partial weightbearing (50% body weight) for 2 weeks, and thence full weightbearing. At 6 weeks, the patient transitioned out of the brace and rehabilitation was a standard post-ACL reconstruction regime focusing on restoring strength of the limb and ‘core’, range of motion, and proprioception.

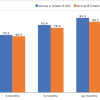

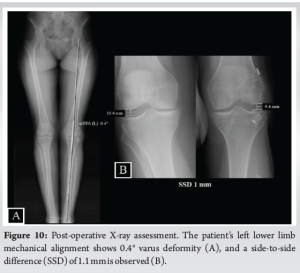

At 24-month follow-up, the operated knee ROM was −5°–130°, with the contralateral knee having −5–135° (Fig. 9). The knee had normal clinical testing for ACL and PLC as well as for the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). However, a side-to-side difference of 1 mm was noted on varus stress X-rays at 20° flexion, but there was symmetry at 0°. The patient was able to return to work as a nurse and to a higher level of sports activity, regularly attending the gym, running on the treadmill and cycling. Tegner, Lysholm, and IKDC subjective scores were 4, 100, and 88.5%, respectively.

This case report’s most important finding is that symptomatic knee instability after proximal fibula resection may be effectively treated by a non-anatomic tibial-based PLC reconstruction. Instability following proximal fibula resection is reported as occurring in 3.9% to 16.7% of cases [4,5,6]; however very few authors have described its treatment in this scenario. In a study of proximal fibular tumours, Bickels et al. [3] reported that 4.2% (1/24) patients had symptomatic knee instability after proximal fibula resection with combined FCL and biceps femoris repair, severe enough to require wearing a knee brace. In a similar population, Arikan et al. [4] and Zhao et al. [5] reported 16.7% (1/6) and 11.1% (2/18) of permanent symptomatic knee instability requiring knee bracing, respectively. All four of the symptomatic patients from these reports underwent wide extra-compartmental proximal fibula Malawer type II resection, which compared to the marginal Malawer type I resection [16] had a higher risk of lateral knee instability [3-5]. This may be related to shorter FCL and biceps femoris remnant stumps, and less viable adjacent soft tissue making repair difficult and healing less likely. In contrast, the patient in the present report developed persistent knee instability after Malawer type I resection combined with FCL and biceps femoris repair. This may be explained by the concomitant ACL deficiency which also likely contributed to this patient’s symptomatic instability [8-10]. Fibular [12,13] and tibiofibular based [8] reconstructions are the gold standard surgical treatment for PLC injuries, with comparable clinical outcomes and being equally effective in restoring varus and rotational stability [14]. In the case presented, as the fibular head was absent, no contemporary PLC techniques were feasible. Therefore, the technique described by Pache et al. was modified to fix both limbs of the PLC graft on to the proximal tibia [15]. The distal FCL placement was directed at the tibial side of the STFJ. Based on anatomical and biomechanical studies [2,8], the distal FCL graft attachment site was found to be at the point of maximum FCL tension in full extension, with slackening in flexion, and found to be 8 mm posterior to the anterior limit and 25 mm distal to the superior limit of the STFJ, respectively. The authors acknowledge this is a non-anatomic PLC reconstruction technique which has not been validated from a biomechanical or clinical point of view, but felt it provided the best biomechanical approach considering the anatomic limitations present. Arguably with the lack of a positive dial test and therefore function from the popliteus complex, the popliteus component of the reconstruction may not have been necessary, but it was decided to include this not to risk inadequate reconstruction. Despite these concerns, at 24 months follow-up, the patient reported no subjective knee instability, had almost symmetrical knee ROM and practically symmetric varus stability as confirmed by stress radiographs. She was also able to return to work and sports activities without restrictions or bracing.

This case highlights the good outcome possible from the non-anatomic PLC tibial-based reconstruction presented. Indeed, this is the first case report describing a tibial-based PLC reconstruction. In complex knee instability cases related to proximal fibula loss from trauma, tumors, or harvesting, when standard techniques are not possible, this non-anatomic tibial-based PLC reconstruction should be considered to restore knee stability.

A PLC repair performed during proximal fibular resection may have a higher risk of major clinical failure if there is a pre-existing ACL deficiency. In this case, ACL reconstruction and tibial-based revision PLC reconstruction should be considered to restore knee stability.

References

- 1.Brinkman JM, Schwering PJ, Blankevoort L, Kooloos JG, Luites J, Wymenga AB. The insertion geometry of the posterolateral corner of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:1364-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.LaPrade RF, Ly TV, Wentorf FA, Engebretsen L. The posterolateral attachments of the knee: A qualitative and quantitative morphologic analysis of the fibular collateral ligament, popliteus tendon, popliteofibular ligament, and lateral gastrocnemius tendon. Am J Sports Med 2003;31:854-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Bickels J, Kollender Y, Pritsch T, Meller I, Malawer MM. Knee stability after resection of the proximal fibula. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;454:198-201. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Arikan Y, Misir A, Gur V, Kizkapan TB, Dincel YM, Akman YE. Clinical and radiologic outcomes following resection of primary proximal fibula tumors: Proximal fibula resection outcomes. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019;27:2309499019837411. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Zhao SC, Zhang CQ, Zhang CL. Reconstruction of lateral knee joint stability following resection of proximal fibula tumors. Exp Ther Med 2014;7:405-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Ben Amotz O, Ramirez R, Husain T, Lehrman C, Teotia S, Sammer DM. Complications related to harvest of the proximal end of the fibula: A systematic review. Microsurgery 2014;34:666-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Kannus P. Nonoperative treatment of grade II and III sprains of the lateral ligament compartment of the knee. Am J Sports Med 1989;17:83-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.LaPrade RF, Johansen S, Wentorf FA, Engebretsen L, Esterberg JL, Tso A. An analysis of an anatomical posterolateral knee reconstruction: An in vitro biomechanical study and development of a surgical technique. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1405-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.LaPrade RF, Resig S, Wentorf F, Lewis JL. The effects of grade III posterolateral knee complex injuries on anterior cruciate ligament graft force. A biomechanical analysis. Am J Sports Med 1999;27:469-75. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Sugita T, Amis AA. Anatomic and biomechanical study of the lateral collateral and popliteofibular ligaments. Am J Sports Med 2001;29:466-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Bonanzinga T, Zaffagnini S, Grassi A, Marcheggiani Muccioli GM, Neri MP, Marcacci M. Management of combined anterior cruciate ligament-posterolateral corner tears: A systematic review. Am J Sports Med 2014;42:1496-503. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Fanelli GC, Larson RV. Practical management of posterolateral instability of the knee. Arthroscopy 2002;18:1-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Arciero RA. Anatomic posterolateral corner knee reconstruction. Arthroscopy 2005;21:1147. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Boksh K, Ghosh A, Narayan P, Divall P, Aujla R. Fibular-versus tibiofibular-based reconstruction of the posterolateral corner of the knee: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 2023;2023:3635465221138548. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Pache S, Sienra M, Larroque D, Talamás R, Aman ZS, Vilensky E, et al. Anatomic posterolateral corner reconstruction using semitendinosus and gracilis autografts: Surgical technique. Arthrosc Tech 2021;10:e487-97. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Malawer MM. Surgical management of aggressive and malignant tumors of the proximal fibula. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1984;186:172-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]