Lateral femoral condyle osteonecrosis of the knee, a rare condition more commonly seen in the elderly and rarely in the young, requires thorough pre-operative clinical and radiological evaluation, consideration of the patient’s age and expectations, and intraoperative correlation to determine the optimal management approach, with total knee arthroplasty being the only viable option in advanced cases with extensive involvement.

Dr. Adarsh Krishna K Bhat, Department of Orthopaedics, Orthopaedics and Joint Replacement Surgery, Apollo Hospitals, Bannerghatta Road, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: adarshbhat118@gmail.com

Introduction: Femoral condyle osteonecrosis of the knee leading to osteoarthritis is a rare entity, which is noticed more commonly in elderly women. Usually, the medial condyle is involved; lateral condyle involvement is extremely rare. Cases like these with occurrence in young individuals are even more rare and need thorough pre-operative evaluation, patient counseling, and intraoperative correlation for proper line of management. Based on the size and stage of the lesion, treatment options vary from medical management to biological therapies to arthroplasty in advanced cases.

Case Report: A 17-year-old male with a body mass index of 29.6 presented to our outpatient clinic with complaints of pain over the left knee, difficulty in walking, squatting, and sitting cross-legged. He was examined clinically, radiologically, and intraoperatively based on the findings and was diagnosed with osteonecrosis of the lateral femoral condyle femur extending into the trochlea with arthritic changes. After detailed discussion and counseling with the patient and relatives, keeping in mind the patient’s demand and expectations, he underwent robotic-assisted total knee arthroplasty (TKA).

Discussion: Knee osteonecrosis is a debilitating, progressive degenerative disease characterized by subchondral bone ischemia. It can lead to localized necrosis, tissue death, and progressive joint destruction. For this reason, it is essential to diagnose and treat this disease early to avoid subchondral collapse, chondral damage, and end-stage osteoarthritis, where the only management option is TKA.

Conclusion: Osteonecrosis of the knee in young patients, particularly when there is extensive articular involvement and associated osteoarthritic changes, is quite challenging to treat. Although joint preservation is typically preferred in younger individuals, TKA may be the only viable option in advanced stages to restore function and quality of life. Robotic-assisted TKA allows for precise implant positioning and optimal alignment and thus enhances the functional outcome. Individualized treatment planning, thorough pre-operative evaluation, and comprehensive patient counseling are essential to achieving successful outcomes in such rare and complex cases.

Keywords: Lateral femoral osteonecrosis, robotic total knee replacement, osteoarthritis.

Osteonecrosis is a devastating disease that can lead to end-stage arthritis of various joints, including the knee [1]. There are three categories of osteonecrosis that affect the knee: Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee, secondary, and post-arthroscopic [2]. Regardless of osteonecrosis categories, the treatment of this disease aims to halt further progression or delay the onset of end-stage arthritis of the knee. However, once substantial joint surface collapse has occurred or there are signs of degenerative arthritis, joint arthroplasty is the most appropriate treatment option. At present, the non-operative treatment options consist of observation, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, protected weight bearing, and analgesia as needed [3]. Operative interventions include joint-preserving surgery, unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA), or total knee arthroplasty (TKA), depending on the extent and type of disease. Joint preserving procedures (i.e., arthroscopy, core decompression [3], osteochondral autograft, and bone grafting, mosaicplasty, novel stem cell therapy, matrix induced autologous chondrocyte implantation) are usually attempted in pre-collapse and some post-collapse lesions, when the articular cartilage is generally intact with only the underlying subchondral bone being affected [4]. Conversely, after severe subchondral collapse has occurred, procedures that attempt to salvage the joint are rarely successful, and joint arthroplasty is necessary to relieve pain [5].

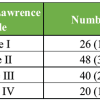

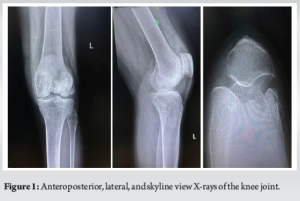

A 17-year-old male with a body mass index of 29.6 presented to our department with complaints of pain over the left knee, difficulty in walking, climbing stairs, squatting, and sitting cross-legged. Detailed history revealed that the patient was diagnosed with ankylosing spondylitis and was prescribed oral steroids for a long duration. He is also diagnosed with clinical depression secondary to the knee disease affliction, and is undergoing pharmacotherapy for the same. He started experiencing pain, locking of the knee in flexion, and difficulty in day-to-day activities, for which he consulted several doctors and was managed conservatively for the same. Despite the ongoing treatments, the patient was not relieved of his symptoms and came to our center for further management. Physical examination revealed lateral joint line tenderness, restricted and painful range of motion with flexion up to 100°. Pre-operative recorded Oxford Knee Score (OKS) was 16, Knee Society Scoring (KSS-K) system of 47, and KSS-F (Functional) of 45. There was no evidence of laxity or instability. On radiological examination, the left knee anteroposterior (AP), lateral, and skyline X-ray (Fig. 1) revealed femoral lateral condyle and trochlea articular surface irregularities with sclerotic changes, subchondral collapse, reduced joint space, and the presence of a loose body in the lateral femoral gutter. Cystic lesions were also noted in the medial femoral condyle with marginal osteophytes. Secondary osteoarthritic changes were noted predominantly in the lateral compartment. The standing X-ray scanogram revealed a valgus alignment of the limb (Fig. 2).

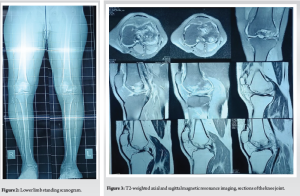

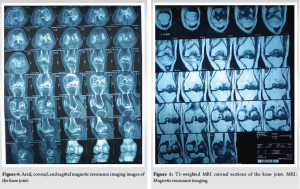

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan of the knee (Figs. 3, 4, 5) was done which revealed large serpiginous areas of lowsignal intensity on T1W images with double line sign and rim sign on T2W images involving whole of lateral femoral condyle and trochlear surface, subchondral bone collapse and bone marrow edema in lateral femoral condyle, trochlear surface and also part of the medial femoral condyle. Mild joint effusion, along with osteoarthritic changes, was noted.

Considering the findings present in the MRI and X-rays, which revealed involvement of the trochlear surface and medial compartment which was although minimal, the option of performing UKA (unicondylar knee arthroplasty) on the lateral condyle seemed questionable. Hence, after thorough discussion with the patient, and keeping in mind the patient’s demands and expectations, TKA with robotic assistance was planned and executed. 3D computed tomography (CT) of the knee with the limb obtained as per Cuvis Robotic system guidelines, and planning for the TKA was done using Cuvis J planner software. The CT scan confirmed and correlated well with the findings of the MRI and X-rays.

Surgical steps

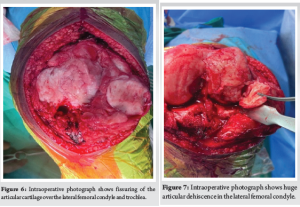

A midline incision using the conventional medial parapatellar approach to the knee was made. Intraoperative examination revealed fissuring and loss of articular cartilage with alteration in the morphology of both medial and lateral femoral condyles (Fig. 6). Large articular cartilage dehiscence with defect noted in the lateral femoral condyle (Fig. 7). A loose bodymeasuring around 5 × 3 cm was retrieved from the lateral femoral gutter. Intraoperative tissue samples were sent for histopathological examination, which later confirmed the diagnosis of chronic synovitis with bone osteonecrosis. Femoral and tibial marker pin inserted and bony registration done. Gap balancing using a robotic-assisted system (CUVIS® Robotic Joint System) was done. The cuts were performed according to the gap-balancing principles to attain perfect mechanical alignment and balance mediolateral gaps in all ranges of movements from full extension to full flexion, which were assessed in real-time by the robot. The trial prosthesis was inserted, and kinematics were tested, including patellofemoral joint tracking. The final implantation was done using cemented femoral components of size H, tibial components of size 5, and a fixed bearing tibial insert of 9 mm thickness (Maxx Freedom TKA System, Meril®, IN). The mediolateral and AP stability, along with patella tracking, were ascertained during trial and after final implantation. No major complications, such as infection, wound breakdown, deep venous thrombosis, or vascular injury, occurred. The post-operative radiograph revealed a well-aligned and well-fixed prosthesis (Fig. 8). The patient was made to walk comfortably on the same day and was very satisfied with the final outcome. At the latest 3rd-month follow-up, the radiographs showed a well-fixed prosthesis (Fig. 9). The patient had a stable knee with a good range of motion of 0–110° (Fig. 10) with OKS of 42, KSS-K score of 88, and KSS-F score of 90, which had improved significantly compared to the pre-operative recorded score.

There are several options in the treatment of symptomatic valgus knee deformity, such as arthroscopic debridement, osteotomy (femoral and tibial side), UKA, and TKA. In determining the operative method, the patient’s age, the desired level of physical activity, the cause of symptoms, and the degree of the deformity should be considered [6]. For patients <60 years old with high physical demands, osteotomy is recommended rather than arthroplasty. The main osteo-cartilaginous lesion occurs on the femoral side in lateral gonarthrosis. When the osteotomy is performed on the tibial side in primary lateral gonarthrosis, unacceptable joint obliquity may occur after surgery. The result is unsatisfactory and unpredictable. To prevent the post-operative obliquity of the joint, femoral supracondylar osteotomy is preferable than on the tibial side. Some surgeons reported that the operative technique is difficult; however, post-operative rehabilitation is difficult [7,8]. Complications, including delayed union or non-union of the osteotomy and severe joint stiffness requiring manipulation after femoral osteotomy, are reported. With artificial joint replacement, the patient can walk a few days after surgery and start rapid rehabilitation. Complete pain relief may be obtained. There are several potential advantages in UKA compared with TKA, including more normal gait patterns, better range of motion, less soft-tissue dissection, less bleeding associated with lower complication rates, and preservation of bone stock and the cruciate ligament [9,10]. Candidates for UKA must have ligamentous stability, especially the anterior cruciate ligament. The valgus deformity must be passively correctable before surgery because it is difficult to correct valgus with UKA. When the patient does not have a lean physique and has moderate-to-severe symptoms resulting from the patellofemoral joint, TKA should be selected rather than UKA. When the valgus knee is overcorrected to varus by UKA, the medial compartment has higher mechanical stress and deteriorates after surgery. The ideal post-operative alignment in lateral compartment arthroplasty is slight valgus. In such a situation, deterioration of the medial compartment may occur. A surgeon may select TKA instead of UKA because the medial and patellofemoral compartments gradually deteriorate. Cameron et al. [11] reported that 9 of 20 lateral compartment arthroplasties ended with poor results. These authors speculated that the reason for the unsatisfactory results was osteopenia of the lateral tibia plateau and difficulty in correcting the valgus malalignment. Uncorrectable valgus is considered to be a contraindication for UKA; however. Scott and Santore [12] did not find that UKA in the lateral compartment is as successful as in the medial compartment. In their series of 100 consecutive cases, 88 were medial and 12 were lateral. One of the medial replacements (1.1%) and two of the lateral replacements (17%) failed. Active robotic assistive techniques for TKA differ from traditional and computer-assisted navigated techniques in many ways. No extra- or intramedullary guides, no cutting blocks, and no oscillating jigs are needed. Another benefit of the robotic technique might be the accurate planning of the milling track and the type of cutting used. This should result in a reduced risk for injury of ligaments, vessels, and nerves, which are undoubtedly endangered by manually directed oscillating saws. The osseous insertion of the posterior cruciate ligament, for instance, can always be preserved. Implants fit better because the milled surfaces are always precisely flat; a matter of particular importance when cementless systems are used. Finally, the amount of removed bony substance can be minimized, which could facilitate later revision surgery. However, in this particular patient, the robotic UKA plan was deferred in view of the extensive involvement of the later condyle and trochlear surface. Although for a young age patient, joint preservation surgery or a UKA would be an ideal mode of management, in cases with extensive articular cartilage damage with secondary osteoarthritic changes, TKA may be the ultimate and final option to improve the patient’s quality of life. A clear advantage of robot-assisted TKA seems to be the ability to execute a highly precise pre-operative plan based on CT scans and intraoperatively achieve balanced flexion-extension medio-lateral gaps [13]. Due to better alignment of the prosthetic components and improved bone-implant fit, implant loosening is anticipated to be diminished. Limitations of the report are the unavailability of the details of earlier medical treatment history related to ankylosing spondylitis and the lack of long-term follow-up results of the patient. This is a unique, rare, and single case report, and the findings cannot be generalized to the broader population. Alternate joint preservation procedures, which must be the first line of management at such a young age, could not be opted for considering the patient’s condition and his expectations.

Knee osteonecrosis is a debilitating, progressive degenerative disease characterized by subchondral bone ischemia. It can lead to localized necrosis, tissue death, and progressive joint destruction. For this reason, it is essential to diagnose and treat this disease early to avoid subchondral collapse, chondral damage, and end-stage osteoarthritis, where the only solution is TKA. Secondary osteonecrosis of the knee is a rare disease and, unlike the spontaneous one, involves patients younger than 50 years. It presents a particular set of pathological, clinical, imaging, and progression features. The management of secondary osteonecrosis is determined by the stage of the disorder, the clinical manifestation, the size and location of the lesions, whether the involvement is unilateral or bilateral, the patient’s age, level of activity, general health, and life expectancy. A complete clinical and radiological examination is indispensable during the pre-operative period. Proper patient education and counseling regarding the chances of infection due to long operating hours, vascular injury, multiple revision surgeries in the future, considering the young age, and information about post-operative rehabilitation protocols are of paramount importance.

Lateral femoral condyle osteonecrosis with osteoarthritic changes is quite challenging to treat, especially when the lesion involved is large and in young patients. Although TKA is not advisable at a young age, where joint preservation procedures should be the first choice, this may be the only treatment modality in severe cases that can improve a patient’s overall well-being in a short period of time. A detailed discussion with the patient, proper consent, and documentation explaining the possibility of multiple revision surgeries in the future and the complications associated with it, is indispensable before going ahead with the procedure in such a case.

References

- 1.Ahlbäck S, Bauer GC, Bohne WH. Spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Arthritis Rheum 1968;11:705-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Mont MA, Baumgarten KM, Rifai A, Bluemke DA, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Atraumatic osteonecrosis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000;82:1279-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Woehnl A, Naziri Q, Costa C, Johnson AJ, Mont MA. Osteonecrosis of the knee. Orthop Knowl Online J 2012;10(5) [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Duany NG, Zywiel MG, McGrath MS, Siddiqui JA, Jones LC, Bonutti PM, et al. Joint-preserving surgical treatment of spontaneous osteonecrosis of the knee. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2010;130:11-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Bonutti PM, Seyler TM, Delanois RE, McMahon M, McCarthy JC, Mont MA. Osteonecrosis of the knee after laser or radiofrequency-assisted arthroscopy: Treatment with minimally invasive knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88 Suppl 3:69-75. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Murray PB, Rand JA. Symptomatic valgus knee: The surgical options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1993;1:1-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Cameron HU, Botsford DJ, Park YS. Prognostic factors in the outcome of supracondylar femoral osteotomy for lateral compartment osteoarthritis of the knee. Can J Surg 1997;40:114-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Johnson EW Jr., Bodell LS. Corrective supracondylar osteotomy for painful genu valgum. Mayo Clin Proc 1981;56:87-92. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Grelsamer RP. Unicompartmental osteoarthrosis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:278-92. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Kozinn SC, Scott R. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1989;71:145-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Cameron HU, Hunter GA, Welsh RP, Bailey WH. Unicompartmental knee replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981;160:109-13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Scott RD, Santore RF. Unicondylar unicompartmental replacement for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:536-44. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Rajashekhar KT, Bhat AK, Biradar N, Patil AR, Mangsuli K, Patil A. Gap balancing technique with functional alignment in total knee arthroplasty using the cuvis joint robotic system: Surgical technique and functional outcome. Cureus 2025;17:e78914. [Google Scholar | PubMed]