Simultaneous bilateral THA is an effective and a safe procedure with fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, and more economical, making it favourable for younger, healthier population despite higher transfusion rate.

Dr. Darshan Thippewamy, Department of Orthopaedics, Vydehi Institute of Medical Sciences and Research Centre, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: darshantswamy@gmail.com

Introduction: Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective orthopedic surgery. Patients who go through the surgery experience better functioning and overall satisfaction with their lives. Other medical ailments like rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, developmental dysplasia, and avascular femoral head necrosis require both hips to undergo THA. Retrospective studies suggest simultaneous bilateral THA (sim-BTHA) utilizes fewer hospital resources, brings about a shorter length of stay, as well as fewer complications compared to traditional methods, but does seem to have a higher requirement for blood transfusions. Despite the improvements to this procedure, comprehensive comparisons regarding single-institute approaches are sparse, creating an area of need focused on analysing complications, transfusion rates, and overall hospital length stays.

Aims and Objectives: This study works to evaluate both sim-BTHA and staged bilateral THA (staged-BTHA) with particular concentration on: (1) The variations in complication rates postoperatively, (2) The variations in blood transfusion amounts required postoperatively, (3) The duration of hospital stay in proportional to the surgery.

Materials and Methods: This study is a prospective cohort study that runs from January 2016 to June 2024 with a target sample size of 89 patients (44 sim-BTHA, 45 staged-BTHA). Patients were divided on the basis of age, gender, diagnosis, and other clinical parameters like ASA grade, comorbidities, hemoglobin, and bone stock, with lower-age, healthier patients in sim-BTHA group. All groups underwent a standard posterolateral approach as well as uniform perioperative protocols. Details including complications, transfusions, and length of stay were retrieved from the medical records and post-operative follow-up period of 3 months.

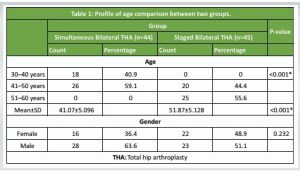

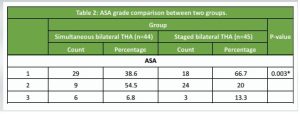

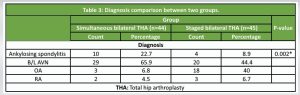

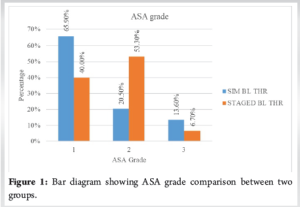

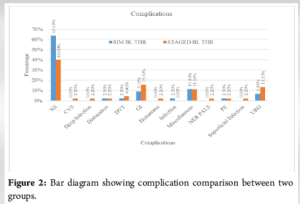

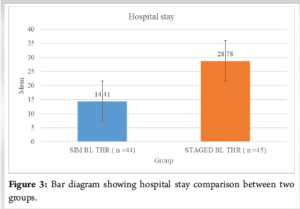

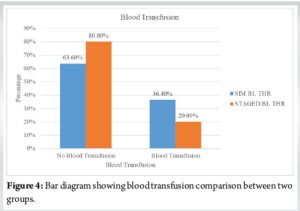

Results: Rates of complications were similar (36.3% sim-BTHA vs. 60% staged-BTHA, P = 0.588). Sim-BTHA was associated with lower medical complications (Gastrointestinal: 9.1% vs. 15.6%). Compared surgical complications were similar; however, deep infections and hematomas occurred only in staged-BTHA (2.2% each). Higher transfusions were seen in sim-BTHA (36.3% vs. 20%, P = 0.086). There was a significant difference in hospital stays with sim-BTHA having shorter stays than staged BTHA (14.4 vs. 28.8 days, P < 0.001). Patients with Sim-BTHA were younger (P < 0.001), had a lesser ASA score (ASA grade 1: 65.9% vs. 40%, P = 0.003), and more diagnosed cases of ankylosing spondylitis (P = 0.002).

Conclusion: For younger and fitter patients, Sim-BTHA appears to be safe, with greater complications seen in staged BTHA, increased transfusion needs, and shorter hospital stays. This supports increased usage in ideal candidates.

Keywords: Simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasty, staged bilateral total hip arthroplasty, bilateral total hip arthroplasty, hip replacement.

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) is an effective orthopedic surgery. Patients who go through the surgery experience better functioning and overall satisfaction with their lives. Other medical ailments like rheumatoid arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, developmental dysplasia, and avascular femoral head necrosis require both hips to undergo THA [1]. Siraj et al. mention that patients with unilateral THA might have to undergo the other knee replacement surgery in <10-year time [2]. Simultaneous bilateral THA (sim-BTHA), the first of which was performed by Charnley in 1971, has received a lot of attention from research communities[3]. Stavrakis et al. introduced sim-BTHA, pointing out the complications to be much less than those found in unilateral THA, suggesting a much safer alternative [4]. The positive outcomes of using sim-BTHA have been presented in various studies [5-7]. Rasouli et al. pointed out that while sim-BTHA poses a greater risk of systemic complications than unilateral THA, it is safer than staged procedures when performed in one hospitalization, particularly for younger, healthier males [8]. Parvizi et al. [9] and Yoshi et al. [10] note that sim-BTHA results in lower costs, lower number of complications, and better recovery outcomes after surgery for both sides of the hip osteoarthritis. Aghayev et al. reported that sam-BTHA, compared to staged bilateral THA (staged-BTHA) had less systemic complications [11], which Parvizi et al. found no significant difference [12]. Ritter and Stringer [13] and Berend et al. [14] highlight the benefits of sim-BTHA, claiming reduced length of hospital and enhanced patient recovery post-surgery. In the sim-BTHA surgeries performed in the lateral decubitus position, transfusions and complications were noted to increase by Berend et al. [14]. Afsar et al. in [15] and a meta-analysis in [16] confirm increased total blood loss and shorter hospital stays. Bhan, in his randomized study, noted that while the control group had longer hospital stays, they required fewer transfusions, whereas the sim-BTHA group had streamlined discharge processes amid increased transfusions [17]. Multidisciplinary approaches, including changes in surgical techniques and postoperative management, have enhanced the results of sim-BTHA.

Our hypothesis states that “patients undergoing sim-BTHA versus staged-BTHA will have differing rates of postoperative complications, postoperative blood transfusion requirement, and lengths of hospital stays.

Patient data

To examine the rates of postoperative complications, postoperative blood transfusion rates, and length of hospital stay between patients undergoing sim-BTHA and staged-BTHA, our study is a prospective cohort study. Among the suggested inclusion criteria are:

- Patients who underwent bilateral primary THA in the period extending from January 2016 to June 2024

- Sim-BTHA

- Staged-BTHA

- Length of hospital stay, post-operative problems, and requirement of blood transfusion for the patients in the above-listed categories.

The proposed exclusion criteria include:

- Patients with existing knee osteoarthritis

- Individuals who had blood coagulation issues or anemia prior to surgery

- Patients with existing bone tumors

- Patients with existing spine disorders.

Out of 89 patients, 44 of them underwent sim-BTHA and 45 of them undergoing staged-BTHA. Informed consent was taken from each patient and their kin. Ethical committee clearance was obtained from the ethics committee of our institution.

Surgery process and post-operative management

The surgery was done according to the standard posterolateral approach [18].

Perioperative management protocol

We allotted the patients into two categories as to whether sim-BTHA or staged-BTHA based on a detailed assessment and discussion about the following parameters related to the patient.

- Age

- Gender

- Diagnosis

- ASA grade

- Presence of comorbidities

- Blood Hb levels

- Presence of viable bone stock.

And the accurate requirement of the type of surgery and taking into consideration the above-mentioned parameters. Young patients with adequate blood hemoglobin and presence of viable bone stock with improved ASA scores were grouped into sim-BTHA group, while the others were grouped into staged-BTHA group. Each patient was admitted to the hospital well prior to the surgery, and detailed pre-anaesthetic evaluation was done and clearance for the proposed surgery was obtained before the surgery. Adequate blood and blood products were arranged. In the operating room, once the anaesthesia was given, the patient was catheterised using a Foley’s in a sterile fashion. Patients in both groups shared a similar mobilization protocol, with both of them being mobilized from postoperative day 2.

Data collection and follow-up

We evaluated the inpatient and outpatient medical records of all the patients to collect data and obtain knowledge about the patient’s preoperative status. We collected pre-, intra-, and post-operative data from all patients’ medical records as well as outpatient notes, focusing on post-operative issues, blood transfusion volumes, and length of hospital stay. Pre-operative information included the age, sex, and diagnosis of each patient. Patients were asked to revisit the hospital 3 months following discharge and evaluated. Those who failed to return were contacted through phone and email, and discussed and assessed for the occurrence of any complications (Table 1).

Complications

For the purpose of research and review, we divided the postoperative complications into 2 groups, namely medical and surgical complications.

- Medical complications:

There are cardiovascular, neurological, digestive, pulmonary, urologic, and other problems.

- Surgical complications:

Hematoma, hip dislocation, nerve palsy, deep periprosthetic joint infection, and superficial wound infection.

The occurrences of complications are direct toward negative outcomes and are hindrances to the safety of the procedure.

For further detailing of our study and better understanding, we define “medical complications” into the following systems–

- Cardiovascular system- Myocardial infarction, frequent angina, cardiac arrhythmia

- Respiratory system- Persistent cough, brief hypoxia, infection, exacerbation of persistent pulmonary obstructive disorder

- Gastrointestinal (GI) system- Stress ulcers, peptic ulcers, GI irritation, post-operative nausea, vomiting, constipation

- Urology- urinary retention, urinary tract infections

- Pulmonary embolism

- Deep vein thrombosis.

Any other disturbances not included above to be included under the miscellaneous category.

Statistical analysis [19-21]

Data was entered into a Microsoft Excel data sheet and was analyzed using Statistical Packages for the Social Sciences 22 version software and Epi-info version 7.2.1 (CDC Atlanta) software. Categorical data was represented in the form of frequencies and proportions. Chi-square test was used as a test of significance for qualitative data. Continuous data was represented as mean and standard deviation. Normality of the continuous data was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and the Shapiro–Wilk test. Independent t-test was used as test of significance to identify the mean difference between two quantitative variables. Mann–Whitney U-test was used for non-parametric data between two groups.

Graphical representation of data

MS Excel and MS Word were used to obtain various types of graphs, such as bar diagram.

P-value (Probability that the result is true) of <0.05 was considered as statistically significant after assuming all the rules of statistical tests.

Statistical software

MS Excel, SPSS version 22 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Somers NY, USA) was used to analyze data.

- Profile of age comparison between two groups (Table 2)

- ASA grade comparison between two groups (Table 3 and Fig. 1)

- Diagnosis comparison between two groups (Table 4)

- Complication comparison between two groups (Table 5 and Fig. 2)

- Hospital stay comparison between two groups (Table 6 and Fig. 3)

- Blood transfusion comparison between two groups (Table 7 Fig. 4).

Medical complications

Medical complications

We found that none of the patients in the sim-BTHA group experienced any postoperative cardiovascular problems, but one patient (2.2%) in the staged-BTHA group did. We discovered that none of the patients in either group experienced pulmonary problems following the operation. We discovered that there were around 4 patients (9.1%) in the sim-BTHA group who developed GI problems, while 7 (15.6%) of them developed such complications in the staged-BTHA group. We also discovered that 3 patients (6.8%) in the sim-BTHA group had urological problems post-surgery, while 6 patients (13.3) in the staged-BTHA group had such problems post-procedure. Another finding was that 1 patient (2.3% in the simultaneous group and 2.2% in staged group) in each group developed pulmonary thromboembolism post-procedure. 1 patient (2.3%) in the sim-BTHA group had deep vein thrombosis, whereas 2 patients (4.4%) in the staged-BTHA group developed deep vein thrombosis. We found out that there were another 4 patients (9.1%) in the sim-BTHA group who had miscellaneous complications, whereas there were around 5 (11.3) of them in the staged-BTHA group who had those complications.

Surgical complications

We discovered that one patient (2.3% in the simultaneous group and 2.2% in the staged group) in both the groups had an occurrence of superficial infection, while only in the staged-BTHA group we got to see a patient with deep infection (2.2%). For postoperative dislocation, the circumstances were the same in either group of 1 per each group (2.2%). We found out that no patient in the sim-BTHA group had any occurrence of deep infection or hematoma or nerve palsy, whereas 1 patient (2.2%) had each of these complications in the staged-BTHA.

Length of hospital stay

When it comes to the length of hospital stay in terms of the number of days in the hospital, we discovered that the staged-BTHA group had a greater average of around 29 days, while the sim-BTHA group had a lesser average of around 14 days.

Post-operative blood transfusion

Through our study, we established that there were 16 patients in the sim-BTHA group who had the requirement of post-operative blood transfusion, whereas there were 9 of them in the staged-BTHA group who had such a requirement.

Thorough analysis of all the possible risks and complications that differ between sim-BTHA and staged-BTHA starts with the process of choosing the patients and assigning them to the two groups named in the study. In our study, there are two age groups that we have considered. The simultaneous group has a greater number of younger individuals, while the staged group had considerable number with older ages. Based on our analysis we have found out that the existing difference among the age groups between the two groups in the question is statistically significant (P < 0.001) thus signifying that most patients in the staged-BTHA group were older than the sim-BTHA group as established by Partridge et al. in his study conducted on 2507 individuals who underwent Sim-BTHAs stated that patients were significantly younger and more likely to be male, and had a significantly shorter overall hospital stay [22]. Another observation is the presence of a greater number of males in the simultaneous group (63.6%) than in the staged group (51.1%). On the contrary, the staged group had a greater number of females (48.9%) compared to the simultaneous group (36.4%). However, our data portrays that the difference in the gender distribution between the two groups is not statistically significant (P = 0.232). An important factor to note here is the presence of variation in the diagnosis between the two groups. The simultaneous group has a predominance of ankylosing spondylitis (22.7%), which is more often seen in a younger population as compared to the staged that has a predominance of osteoarthritis (40%) which is a feature of older population. As per our reports, we found out that this difference in the diagnosis distribution is statistically significant (P = 0.002) thereby throwing light on the existence of variation in the underlying conditions leading to the surgery between the two groups. Inoue et al. suggest that the simultaneous bilateral direct anterior approach -THA appears to be a reasonable and safe form of treatment for patients with bilateral symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hip thus throwing light on the statement that the diagnosis plays an important role [23]. The simultaneous group (65.9%) has a greater number of patients with ASA grade 1 while compared to the staged group (40%) that denotes the fact that the individuals in the simultaneous group are more healthy individuals as compared to the other group in question. This difference in the ASA grades between the two groups was statistically significant (P = 0.003), stressing that population of simultaneous group was healthier than the staged group. In a study conducted by Kirschbaum et al., it was found out that patients in the sim-BTHA group were younger and had lower ASA scores than the staged group. However there were no significant differences found concerning the complication rate or early inpatient rehabilitation, concluding that simultaneous bilateral hip arthroplasty in patients with symptomatic bilateral hip osteoarthritis is as safe and successful as a staged procedure if performed by a high-volume surgeon [24]. In extension to the above-mentioned facts, the population in the simultaneous group has individuals with lesser rate of comorbidities and better blood hemoglobin status as compared to their counterparts in the staged group. Also, we have assigned patients into the two groups based on their bone stock viability as well, with the healthier patients with respect to bone stock being assigned in the simultaneous group and the rest into staged group. These are the prevalent differences present between the two groups to be kept in mind on a preoperative level before proceeding with the discussion about post-operative complications [25]. In simultaneous group, we encountered that 16 patients out of the 44 developed certain post-operative complications that amounts to 36.3% of the total population. Whereas in the staged group, there were 27 patients out of 45 who developed post-operative complications, that corresponds to 60% of the total population. The increase in the complication rate among the patients of the staged group points towards that most patients in the staged group were either old or comorbid or the ones with certain health conditions which caused them complications in the post-operative period. However, according to our reports, the existing overall difference in complication rates between the two groups is not statistically significant (P = 0.588). Rezzadeh et al. established that the rate of major complications or death after sim-BTHA was no higher than the projected staged-BTHA rate, thus concluding that sim-BTHA appears safe in patients medically fit to tolerate longer uninterrupted surgery and appears to shorten operative time and hospital stay relative to staged-BTHA [26]. When we talk about the patients who underwent blood transfusion in the either group, we come to know that there were 16 patients out of 44 in the simultaneous group whereas there were 9 patients out of 45 in the staged group who underwent blood transfusion post-procedure. We can appreciate the difference in the blood transfusion rates as it is around 36.3% in the simultaneous group, whereas it is around 20% in the staged group. Although the simultaneous group had a higher rate of blood transfusions, an important factor to note here is that this existing difference is not statistically significant (P = 0.086). This is mostly because sim-BTHA involves incorporation of two separate procedures to one and therefore causing a noticeable amount of blood loss resulting in a sharp drop in post-operative hemoglobin thus leading to the requirement of blood transfusion post procedure while in the staged group, the final blood loss post procedure was not as much as in the simultaneous group thus leading to a lesser number of patients requiring blood transfusion after the procedure. In a study by Koutserimpas et al. it is stated that the blood loss was higher in the sim-BTHA group, but there was no significant difference in transfusion rates, and concluded by establishing that sim-BTHA seems to be a safe procedure, with no risk of increased early postoperative complications when compared to the staged procedure with similar functional outcomes [27]. The total length of hospital stays when measured in the number of days we learn that for simultaneous group, since the two procedures are clubbed into one and done in one setting, the duration of hospital stay remains less as compared to the staged group because it involves hospitalization twice and therefore the total duration of the hospital stay becomes almost twice that for simultaneous group. Therefore, in reality, taking into consideration the extra days a patient stays in the hospital due to unexpected post-operative complications across the two groups, the average number of days spent in the hospital comes up to around 14.4 in simultaneous group, whereas it is around 28.8 in the staged group. This difference is statistically important (P < 0.001), indicating that sim-BTHA group had a shorter recovery period in the hospital compared to the staged-BTHA group. To substantiate on this we have found evidence from a retrospective cohort study by Agarwal et al. where in 48 patients underwent sim-BTHA and 56 patients underwent staged-BTHA. The hospital stay was 5.6 days in sim-BTHA and 9.0 days in staged-BTHA, thus concluding that sim-BTHA is a safe procedure. The definite benefits are short hospital stay, lower cost, and early rehabilitation [28]. In summary, the study shows significant differences between the two groups in terms of age distribution, ASA grade, diagnosis, and hospital stay duration, with Group A generally having younger, more healthy patients, shorter hospital stays, and requiring more frequent blood transfusions. However, there was no significant difference in gender distribution, complication rates, or blood transfusion rates [29]. One major limitation to our study was that we have generalized the procedure of THR and we have not differentiated into whether the procedure was cemented or uncemented. Owing to the fact that each one of them has different complications to themselves, we have not considered the division into cemented and uncemented procedures while defining complications. Other than this, the sample size we have taken into account maybe small and could have included many more patients in the trial. Furthermore,, patients in the simultaneous group were younger, and compared to the staged group, many of them in the simultaneous group were men, which could amount to being a confounding factor. Additional research is required to confirm our findings.

In particular, for younger and healthier patients, our comparison of sim-BTHA and staged-BTHA demonstrates that the former is a safe and successful operation. There is no statistically significant difference in the overall complication rates between the two groups, even though staged-BTHA had a higher incidence of some specific complications, such as hematomas and deep infections (36.3% for sim-BTHA versus 60% for staged-BTHA with P = 0.588). It’s interesting to note that sim-BTHA was linked to shorter hospital stays (14.4 days versus 28.8 days with P < 0.001), indicating that it works well to reduce recovery times and the need for medical resources. However, Sim-BTHA showed that more frequent blood transfusions were required (36.3% vs. 20% with P = 0.086), mainly due to the total blood loss caused by the two operations performed at the same time. It appears that careful patient selection is required to get the greatest results because most of the patients in the sim-BTHA group were younger, had lower ASA grades, and had minimal comorbidities. The higher occurrence of diagnoses such as osteoarthritis in the staged-BTHA cohort and ankylosing spondylitis in this group indicated age-related differences in the underlying diseases. Despite having a larger transfusion demand, sim-BTHA is an excellent option for people who require it because it provides clear and noticeable advantages, such shorter hospital stays and comparable safety profiles. These findings support the use of sim-BTHA in clinical practice for carefully chosen patients and demonstrate its benefits in terms of resource management and recovery efficiency. Future research with larger sample numbers and longer follow-ups may be able to validate these results and examine the effects of surgical techniques, such as cemented versus uncemented operations. When considering patient convenience, safety, and efficacy, sim-BTHA is a prudent choice for bilateral hip replacements.

We have to incorporate the practice of sim-BTHA in increasing numbers, considering the fact that it is a safe procedure with fewer medical and surgical complications with a shorter hospital stay period.

References

- 1.Guo SJ, Shao HY, Huang Y, Yang DJ, Zheng HL, Zhou YX. Retrospective cohort study comparing complications, readmission, transfusion, and length of stay of patients undergoing simultaneous and staged bilateral total hip arthroplasty. Orthop Surg 2020;12:233-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Harris WH. The first 50 years of total hip arthroplasty: Lessons learned. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:28-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Sayeed SA, Johnson AJ, Jaffe DE, Mont MA. Incidence of contralateral THA after index THA for osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:535-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Stavrakis AI, SooHoo NF, Lieberman JR. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty has similar complication rates to unilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:1211-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Jaffe WL, Charnley J. Bilateral charnley low-friction arthroplasty as a single operative procedure. A report of fifty cases. Bull Hosp Joint Dis 1971;32:198-214. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Kim YH. Bilateral cemented and cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2002;17:434-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Schäfer M, Elke R, Young JR, Gancs P, Kindler CH. Safety of one-stage bilateral hip and knee arthroplasties under regional anesthesia and routine anesthetic monitoring. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:1134-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Rasouli MR, Maltenfort MG, Ross D, Hozack WJ, Memtsoudis SG, Parvizi J. Perioperative morbidity and mortality following bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:142-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Parvizi J, Tarity TD, Sheikh E, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: One-stage versus two-stage procedures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;453:137-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Yoshii T, Jinno T, Morita S, Koga D, Matsubara M, Okawa A, et al. Postoperative hip motion and functional recovery after simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasty for bilateral osteoarthritis. J Orthop Sci 2009;14:161-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Aghayev E, Beck A, Staub LP, Dietrich D, Melloh M, Orljanski W, et al. Simultaneous bilateral hip replacement reveals superior outcome and fewer complications than two-stage procedures: A prospective study including 1819 patients and 5801 follow-ups from a total joint replacement registry. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:245. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Parvizi J, Pour AE, Peak EL, Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH. One-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty compared with unilateral total hip arthroplasty: A prospective study. J Arthroplasty 2006;21:26-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Ritter MA, Stringer EA. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: A single procedure. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1980;149:185-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr., Adams JB. Simultaneous vs. Staged cementless bilateral total hip arthroplasty: Perioperative risk comparison. J Arthroplasty 2007;22:111-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Tsiridis E, Pavlou G, Charity J, Tsiridis E, Gie G, West R. The safety and efficacy of bilateral simultaneous total hip replacement: An analysis of 2063 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:1005-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Shao H, Chen CL, Maltenfort MG, Restrepo C, Rothman RH, Chen AF. Bilateral total hip arthroplasty: 1- stage or 2-stage? A meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:689-95. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Bhan S, Pankaj A, Malhotra R. One- or two-stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty: A prospective, randomised, controlled study in an Asian population. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:298-303. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Canale ST, Beaty JH. Total knee arthroplasty. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, editors. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 14th ed. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2021. p. 207-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Yan F, Robert M, Li Y. Statistical methods and common problems in medical or biomedical science research. Int J Physiol Pathophysiol Pharmacol 2017;9:157-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Panos GD, Boeckler FM. Statistical analysis in clinical and experimental medical research: Simplified guidance for authors and reviewers. Drug Des Devel Ther 2023;17:1959-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Dakhale GN, Hiware SK, Shinde AT, Mahatme MS. Basic biostatistics for post-graduate students. Indian J Pharmacol 2012;44:435-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Partridge TC, Charity JA, Sandiford NA, Baker PN, Reed MR, Jameson SS. Simultaneous or staged bilateral total hip arthroplasty? An analysis of complications in 14,460 patients using national data. J Arthroplasty 2019;35:166-71. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Inoue D, Grace TR, Restrepo C, Hozack WJ. Outcomes of simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasty for 256 selected patients in a single surgeon’s practice. Bone Joint J 2021;103-B:116-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Kirschbaum S, Hube R, Perka C, Ley C, Rosaria S, Najfeld M. Bilateral simultaneous hip arthroplasty shows comparable early outcome and complication rate as staged bilateral hip arthroplasty for patients scored ASA 1-3 if performed by a high-volume surgeon. Int Orthop 2023;47:2571-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Loth FL, Giesinger JM, Giesinger K, MacDonald DJ, Simpson AH, Howie CR, et al. Impact of comorbidities on outcome after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:2755-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Rezzadeh K, Nigh E, Debbi E, Rajaee S, Paiement J. A NSQIP analysis of complications after simultaneous bilateral total hip arthroplasty. J Hip Surg 2023;7:72-80. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 27.Koutserimpas C, Rob E, Servien E, Lustig S, Batailler C. Similar complications and outcomes with simultaneous versus staged bilateral total hip arthroplasty with the direct anterior approach: A comparative study. SICOT J 2024;10:31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 28.Comparison between Single Stage and Two Stage Bilateral Total Hip Replacementour Results and Review of Literature. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica; 2016. Available from: https://www.actaorthopaedica.be/archive/volume-82/issue-3/original-studies/comparison-between-single-stage-and-two-stage-bilateral-total-hip-replacementour-results-and-review [Last accessed on 2025 Feb 07]. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 29.Panchal S, Jogani AD, Mohanty SS, Rathod T, Kamble P, Keny SA. Is bilateral sequential total hip replacement as safe an option as staged replacement? A matched pair analysis of 108 cases at a tertiary care centre. Indian J Orthop 2021;55:1250-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]