This short case series evaluated the outcomes of four patients who had giant cell tumors surrounding their knees treated with intralesional curettage, phenol application, and sandwich technique reconstruction at our institution.

Dr. Kevin Jose, Department of Orthopaedics, St. John’s Medical College Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. Email: kevinjosek1995@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumors (GCT) are benign yet locally aggressive neoplasms. The primary objectives of treatment are to entirely eliminate the tumor, rebuild the defect, and restore limb functionality. Numerous surgical treatment options have been proposed, ranging from more drastic interventions, such as en bloc excision, to less invasive techniques such as curettage or curettage combined with bone grafting. Limited research addresses the functional outcomes following treatment for giant cell tumors, despite the abundance of publications focusing on cure rates, recurrence, and other surgical considerations of the condition.

Case Report: Three Individuals aged 20–40 are typically the ones affected with GCT. Patients typically exhibit pain during rest or sleep, and in certain instances, may also experience pathologic fractures. All patients were clinically evaluated, plain X-ray of the knee, chest X-ray, computed tomography , and magnetic resonance imaging were taken before the procedure. In all patients a pre-operative, a biopsy was performed to determine the tumor’s histological grade and to confirm the diagnosis.

Conclusion: The sandwich technique is an appropriate reconstructive procedure for GCT around the knee joint, involving the use of polymethylmethacrylate to occupy the residual cavity post-curettage, the placement of a structural allograft in the subchondral region, and the application of a gel form in the intervening space. It also has less complications, favorable survival rates, and positive functional outcomes. This approach preserves the advantages of cementing, mitigates potential complications, and restores the subchondral bone stock. None of our patients experienced any collapse of the joint, recurrences, immunological complications. All of them also had good functional status of the limb after 1 year. Thus, knee based on our good findings, we advocate this technique for joint salvage in GCTs around the knee.

Keywords: Sandwich technique, giant cell tumor, functional outcome.

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) constitute 5% of primary bone tumors and are classified as benign although they are locally aggressive neoplasms [1]. The proximal tibia and distal femur are the most often affected areas, followed by the distal radius [2]. The closeness of these epi-metaphyseal lesions to articular surfaces poses therapeutic problems. Individuals between 20 and 40 years are often affected [3,4]. Patients typically first present with pain during rest or sleep, and in some instances, experience pathologic fractures, especially in weight-bearing bones [5]. The GCT treatment primarily focuses on complete tumor eradication, defect reconstruction, and restoration of limb function [6]. A variety of surgical modalities have been suggested, from radical procedures such as en bloc excision to less invasive techniques, including curettage and curettage supplemented with bone grafting or bone cementing [3,7]. Intralesional curettage is often employed alongside adjuncts such as liquid nitrogen, phenol, and hydrogen peroxide, referred to as extended curettage, to enhance the kill zone and mitigate recurrence rates [3]. This short case series evaluated the outcomes of three patients who had GCTs surrounding their knees treated with intralesional curettage, phenol application, and sandwich technique reconstruction at our institution.

This is a short case series of 3 patients aged 27–30 (mean, 28) years underwent intralesional curettage, use of phenol, and reconstruction using the sandwich technique for GCT in our institute. Institutional ethical clearance was obtained. The objective of our case series was to evaluate prospectively the functional outcome, recurrence rates, complications, and metastasis of patients treated with the sandwich technique for GCT around the knee. Before surgery, patients were clinically evaluated; plain X-ray of the knee [Fig. 1], chest X-ray, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging were taken.[Fig. 2] In every instance, a biopsy was performed to validate the diagnosis.

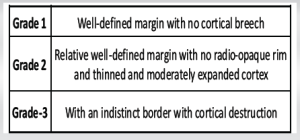

Subjects with degenerative joint changes, pathological fractures, and roentgenograms demonstrating the loss of more than two-thirds of the cortex in a single view substantial subchondral bone stock (>5 mm) following extensive curettage were excluded from this case series. The radiographic characteristics were taken into consideration and were classified based on the classification given by Campanacci et al. [10].

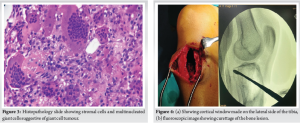

In all 3 cases, pre-operative biopsy was utilized to establish the diagnosis for each patient, and intraoperatively acquired samples were dispatched for histological examination, which verified the diagnosis of GCT.[Fig. 3]

The patient was positioned supine under spinal anesthesia. The surgical site was painted and draped. The Incision was made in such a way that included the biopsy scar. A substantial cortical window was made, facilitating sufficient exposure, and curettage was performed until normal bone was visualized.[Fig. 4]

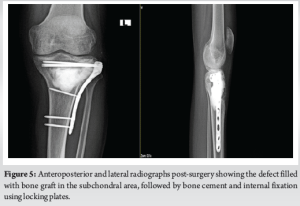

The cavity formed was further enlarged using a high-speed burr, ensuring the surrounding tissue remained uncontaminated. Sufficient samples were collected for histopathological analysis. Pulsatile lavage was given, facilitating the exposure of raw cancellous bone. Subsequently, phenol was instilled; as an adjunct, the remaining cavity was filled with bone cement, pieces of iliac crest graft were then placed in the subchondral region, followed by the application of a gel foam (a biodegradable, non-toxic gel made from human fibrinogen and thrombin) layer beneath them; the bone was then stabilized by internal fixation [Fig. 5] with a proximal tibia locking plate. A drain was inserted and the wound was sutured.

Post-operative protocol

All patients were immobilized using above-knee plaster of Paris slabs.

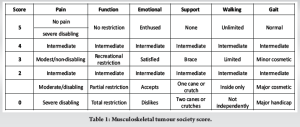

From post-operative day 1, patients were initiated on non-weight-bearing ambulation. Quadriceps strengthening and knee range of motion exercises were commenced 2 weeks later. One-month post-surgery, partial weight-bearing was initiated. Patients were advised to full weight-bearing walking after 3 months. Patients underwent clinical and radiological follow-up for a minimum of 6 months to assess functional outcomes, identify any local surgical complications, and lung metastases. The musculoskeletal tumor society (MSTS) score was used to assess the functional outcome (MSTS) (Table 1)., which includes a subjective clinical evaluation in addition to six parameters: Function, pain, emotional acceptance, walking capacity, usage of walking aids, and gait.

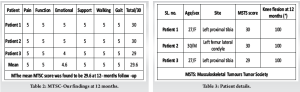

Out of three patients, two patients had lesions in the proximal tibia and one patient had a lesion in the distal femur. Table 2,3]. None of the patients experienced malignant changes.

The mean MSTS score was 29.6. [Table 2]

The mean age of our patients was 28, which is consistent with previous studies [1]. The patients’ ultimate functional results were not significantly impacted by factors such as age, gender, or tumor grade. Increased lysis measuring more than 5 mm at the bone-cement contact or the lack of a sclerotic rim at the interface were considered indicators of tumor recurrence [10]. None of the patients exhibited any recurrence within 6 months; however, an extended follow-up will be essential to accurately assess the recurrence rate. A series of studies by Banerjee et al. on 12 patients with GCT of the distal femur treated with the sandwich technique showed outstanding results, with a mean MSTS score of 26, which is similar to our case series [8].[11] We performed intralesional curettage on all our patients and utilized phenol as an adjunct, which acts by protein coagulation, necrosis, and DNA damage. Studies suggest that recurrences are most probable within the initial 2 years following curettage and can be mitigated with the use of adjuncts (extended curettage) [6]. The biological barrier of periosteum on the posterior aspect keeps bone cement and bone grafts from escaping the hollow. Furthermore, it also inhibits the leakage of phenol, which could result in neurovascular damage [9]. Therefore, during curettage, pre-cautions were implemented to prevent the rupture of the cortex and periosteum in the posterior region [6]. The cavity was filled with poly methyl methacrylate (PMMA) to diminish the recurrence rate, as evidenced by a meta-analysis of six studies including over a thousand patients treated with thorough curettage and filling the formed cavity using allogeneic graft or PMMA [1]. Studies indicate that the recurrence rate of cavities filled with cement is <25%, whereas the recurrence rate of cavities filled with other materials is >50% [8]. The reason being heat generated during the formation of PMMA causes thermal necrosis of the tumor, and the monomer that is formed induces hypoxic tumor necrosis. It also has an ability to show lysis in the bone cement interface in radiographs, facilitating the early detection of recurrence [3]. In sandwich technique we added iliac crest bone graft below the subchondral layer to increase bone stock and an additional layer of gel foam beneath it, following the study of Radev et al. [1] which recommended a minimum of 2–4 mm subchondral bone to protect articular cartilage from degenerative changes due to PMMA’s cytotoxic and exothermic effects [1,3,8]. Since we have used iliac crest autograft, which has got good osteogenic, osteoinductive, and osteoconductive properties, good acceptability of the autograft was observed with a minimal risk of immunological complications. We also employed fixation in every instance, using locking plates and cortico-cancellous screws to stabilize the bone graft and bone cement and lessen the likelihood of collapse. This also promoted early mobilization and improved range of motion [4]. Our own set of constraints included the tiny population cohort of only 3 patients, as well as the absence of a control group. Furthermore, there were differences in the tumor mass’s position and volume. The treatment plan was the same for each patient, though. Finally, our follow-up period was 1 year, which is rather short. Despite the fact that studies have demonstrated that the majority of local recurrences happen before 2 years, certain instances of GCT recurrences have been documented after this time [8]. Degenerative changes in the joints could also take longer to manifest [8] to definitively identify tumor recurrence and evaluate joint failure, we want to monitor these patients for an extended period of time. Even though the outcomes after intermediate follow-up has shown promise. Long-term follow-up is necessary.

Even though there exist many studies that describe the cure rate, recurrence, and other surgical factors, there are a few that address the functional results following GCT treatment using various techniques. This short case series suggests that the sandwich technique following an extended curettage results in satisfactory knee function with few complications and may withstand without articular collapse or fractures, thus can be safely used in selected cases.

In the Sandwich technique, the benefits of cementing are utilized, possible complications are minimized, and subchondral bone is restored. We advocate the sandwich method for joint salvage in GCTs around the knee based on our good findings.

References

- 1.ElDesouqi AA, Ragab RK, Ghoneim AS, Sabaa BM, Rafalla AA. Treatment of giant cell tumor of bone using bone grafting and cementation with versus without gel foam. Alex J Med 2022;58:78-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Ambulgekar RK, Thakkar R, Berlia R, Kothari P, Shrivastava A, Ponde S. Management of a rare recurrence of distal tibial giant cell tumour by sandwich technique. J Evid Based Med Healthc 201;3:650-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Clarke D, Nepaul D, Chindepalli H, Lawson K. The sandwich technique in the management of a peri-articular giant cell tumour of the knee. West Indian Med J 2018;67:148-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Sau DS, Basak DA. Clinical outcome of sandwich technique along with locking plate augmentation in giant cell tumoraround knee. IOSR J Dent Med Sci 2017;16:100-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Aledanni S, Alshahwani ZW, Hussein HR. Functional outcomes of sandwich reconstruction technique for giant cell tumor around the knee joint. Rawal Med J 2020;45:637-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Bharwani N, Singh N, Agarwal S, Jain H, Raichandani K, Saxena M. Functional Outcome of Extended Curettage and Reconstruction for Giant Cell Tumor Around Knee PG Resident 2 Assistant Professor 3 PG Resident 4 Associate professor 5 Senior Professor 6 PG Resident. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Singaravadivelu V, Kavinkumar V. Giant cell tumour around knee managed by curettage and zoledronic acid with structural support by fibula cortical struts. Malays Orthop J 2020;14:42-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Kundu ZS, Gogna P, Singla R, Sangwan SS, Kamboj P, Goyal S. Joint salvage using sandwich technique for giant cell tumors around knee. J Knee Surg 2015;28:157-64. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Saibaba B, Chouhan DK, Kumar V, Dhillon MS, Rajoli SR. Curettage and reconstruction by the sandwich technique for giant cell tumours around the knee. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2014;22:351-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Campanacci M, Capanna R, Fabbri N, Bettelli G. Curettage of giant cell tumor of bone. Reconstruction with subchondral grafts and cement. Chir Organi Mov 1990;751 Suppl:212-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Pettersson H, Rydholm A, Persson B. Early radiologic detection of local recurrence after curettage and acrylic cementation of giant cell tumours. Eur J Radiol 1986;6:1-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Banerjee S, Sabui KK, Chatterjee R, Das AK, Mondal J, Pal DK.Sandwich reconstruction technique for subchondral giant cell tumors around the knee. Curr Orthop Pract 2012;23(5):459–466. [Google Scholar | PubMed]