Various treatment modalities of clavicle fracture has been described and the treatment outcome of each modality along with its pro’s and con’s are described in this study.

Dr. Ganesh MT, Department of Orthopaedics, Sree Balaji Medical College and Hospital, BIHER, Chromepet, Chennai - 600044, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: dr.ganesh@yahoo.com

Introduction: Clavicle fractures account for a significant proportion of shoulder girdle injuries, with varying treatment modalities employed, ranging from conservative management to surgical intervention. This study aims to evaluate the outcomes of clavicle fractures treated conservatively versus those treated with open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF).

Materials and Methods: A retrospective analysis was conducted on 94 patients with clavicle fractures treated between 2019 and 2023. Patients were categorized into two groups: those receiving conservative treatment (n = 52) and those undergoing surgical intervention (n = 42), which included intramedullary fixation using titanium elastic nail system (TENS) and plate and screw fixation. Clinical and radiological data were collected, and outcomes were assessed based on union rates, complications, and functional recovery.

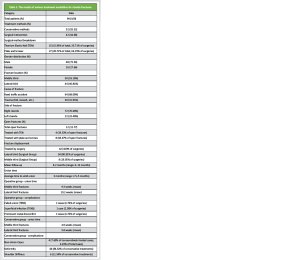

Results: The average time to solid union was 3 months, with conservative treatment yielding a mean of 4.9 weeks for middle-third fractures and 5.8 weeks for lateral-third fractures. The surgical group showed slightly longer healing times (mean 9.3 weeks for middle-third fractures and 10.2 weeks for lateral-third fractures) but achieved higher union rates, with only 2 cases (4.76%) of non-union in the TENS group. In contrast, the conservative group had a non-union rate of 7.69%, predominantly in lateral-third fractures. Malunion occurred in 85% of conservatively treated cases, yet functional impairments were minimal. Surgical intervention resulted in no reported deformities or significant functional deficits.

Conclusions: While conservative treatment is effective for non-displaced fractures, surgical intervention offers significant advantages for displaced fractures, particularly in achieving higher union rates and better functional outcomes. This study reinforces the importance of personalized treatment strategies, emphasizing surgical management in cases of displacement or comminution to minimize complications and improve patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Clavicle fractures, conservative treatment, open reduction internal fixation, intramedullary fixation, plate and screw fixation, titanium elastic nails.

Fractures of the clavicle comprise 44% of all shoulder girdle injuries [1]. They are more common in young men and account for 5–10% of all fractures [2]. The mechanism of injury is either a fall onto an outstretched hand, a fall onto the point of the shoulder, or a direct blow to the shoulder [3]. There are various methods of treating clavicle fractures. Essentially, all the authors who have written on the treatment of clavicle fractures have recommended a conservative approach. Conservative methods described since 1920 include plaster spica casts, strapping, slings, Parham support, Bohler’s brace, Velpeau wrap, and even neglect occasionally. Most fractures unite successfully with one of these treatment methods. However, open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) are required in selected cases. These include: (1) neurovascular compromise due to posterior displacement and impingement of the bone fragments on the brachial plexus, subclavian vessels, and even the common carotid artery; (2) fracture of the distal third of the clavicle with disruption of the coracoclavicular ligament; (3) severe angulation, displacement, skin tenting or comminution of a fracture in the middle third of the clavicle; (4) the patient’s inability to tolerate prolonged immobilization (required by closed treatment) due to Parkinson’s disease, a seizure disorder, or other neuromuscular disease; (5) symptomatic non-union following treatment by closed methods [4]. The implants used for internal fixation of clavicle fractures include circlage sutures, intramedullary devices [5-8] (Steinmann pins, Hagie pins, K wires, Knowles pins, rush nails, titanium elastic nails), and plate and screws [9-11] (reconstruction plate, dynamic compression plate, semitubular plate, and anatomical locking plates). This retrospective study was performed to assess the outcome of clavicle fractures treated by various modalities, both conservative and surgical.

This retrospective study examined 94 cases of clavicle fractures treated between 2019 and 2023 using either conservative methods or surgical intervention, specifically ORIF with plate and screws or titanium elastic nail. Ethical clearance was obtained prior to the study. Medical records, including follow-up details and radiographs, were reviewed for all patients, who were treated as outpatients or inpatients. Relevant data such as age, gender, mechanism of injury, associated injuries, and x-ray findings were meticulously recorded. Follow-up X-rays were taken at 6 weeks, 3 months, and 6 months post-treatment, ensuring that all patients were monitored until clinical and radiological union was achieved. Out of the 94 patients, 52 (55.32%) received conservative treatment. These patients typically presented with closed fractures that were minimally displaced or non-displaced, exhibited no significant comminution, had normal skin condition, and showed no signs of neurovascular compromise. In contrast, 42 patients (44.68%) underwent surgical intervention due to indications for ORIF. Surgical candidates were identified based on factors such as neurovascular compromise from posterior displacement, fracture of the lateral third with ligament disruption, severe displacement with skin tenting in the middle third fractures, inability to tolerate prolonged immobilization due to neurological conditions, and symptomatic non-union following conservative treatment. Among the patients who underwent surgery, 15 (15.96%) were treated with ORIF using a titanium elastic intramedullary nail system (TENS), while 27 (28.72%) received ORIF with a 3.5 mm reconstruction or anatomical locking plate and screws. This study underscores the importance of tailoring treatment strategies based on the specific characteristics of clavicle fractures and the patients’ individual needs.

Procedure

Conservative methods

At first, a closed reduction is attempted. The patient was seated on a stool, and the surgeon stood behind. To reduce the clavicular fracture, the surgeon places his knee between the scapulae and with his both hands the outer edges of the shoulder were held securely and were pulled upward, outward, and backward. Then, the fracture was manipulated into place. In patients with multiple injuries, reduction was done in the supine position. After reduction, strapping was done, and a commercially available clavicle brace was applied. Additional support was given for the arm in all the cases using an arm sling pouch. The patients were assessed clinically and radiologically for evidence of union at 3 weeks, 6 weeks, and 3 months. The patients were allowed for gentle isometric and mobilization exercises after 3weeks but lifting of heavy weights and overhead abduction were delayed up to 3 months.

Operative treatment

The operative treatment for clavicle fractures advocated in our study group was intramedullary fixation using TENS and plate and screw fixation (3.5 mm reconstruction plate or 3.5 mm anatomical clavicle locking plate). The surgery was done under general anesthesia or regional anesthesia (interscalene block) with the patient in supine position with the head turned to the opposite side and a sandbag being placed between the two scapulae. The extremity and the shoulder were draped free so that the entire extent of the clavicle could be exposed.

Intramedullary fixation

No formal incision is required for a closed technique of clavicle fixation with TENS. However, a small skin incision (about 1–2 cm) may be made over the lateral entry point to facilitate nail insertion. The entry point is approximately 1–2 cm medial to the acromioclavicular joint, along the posterio-superior aspect of the clavicle. Use fluoroscopy to confirm the entry point and the trajectory. Utilize a cannulated drill to create a pathway into the medullary canal of the clavicle. Select an appropriate size titanium elastic nail, typically ranging from 2.5 mm to 3.5 mm in diameter. Insert the TEN into the drilled pathway, ensuring that it passes through the fracture site. The nail should extend out the opposite end of the clavicle (approximately 1–2 cm beyond the fracture site) for adequate stabilization. Achieve fracture reduction by applying gentle traction to the arm while simultaneously pushing the nail to align the fracture fragments. Confirm adequate reduction and alignment using fluoroscopy. Once proper alignment is confirmed, the nail can be cut to length, and any protruding ends can be bent back into the clavicle to minimize irritation. Small incision made for entry was closed with skin stapler or Ethilon 3-0. For cases of TENS which required open reduction, a linear incision was placed directly over the fracture site, and dissection was carried down to the bone. Then, with minimal periosteal stripping, the fracture fragments were mobilized. A 2.5 mm k-wire was then drilled into the distal fragment from the fracture site and out through the posterior border of this fragment and the subcutaneous tissue and skin on the posterior aspect of the shoulder. Then, it is removed, and a 2.5 mm titanium elastic nail is introduced into the distal fragment through the fracture site, exiting from the lateral end. It is then backed out through the lateral fragment. The fracture fragments were then reduced and held temporarily by pointed reduction clamps, and the nail is advanced to the proximal fragment across the fracture site. Any loose fragments present were repositioned in their place and secured with encirclage wires if needed. The periosteum and muscles were closed in one layer as a sleeve over the fragments. The wound is then closed in layers.

Plate and screw fixation

The fracture site was exposed as described above. The fracture was reduced using pointed reduction forceps. Then a 3.5 mm reconstruction plate is contoured to the shape of the clavicle (not required if anatomical locking plate is used) and placed over the superior/anterior surface of the clavicle and held temporarily with a cocker forceps or bone clamps in such a way that at least three holes were present on either side of the fracture. Then, drill holes were made using 2.5 mm drill bit, tapped using 3.5 mm tap and 3.5 mm cortical screws were driven to hold both cortices. Any loose fragments present were repositioned in its place and secured with encirclage wires or interfragmentary screw if needed (Fig. 1). A periosteal elevator was placed posterio-inferiorly to prevent penetration of the drill into deeper structures. The muscle and subcutaneous tissue were sutured over a suction drain. Skin closed with Ethilon no.3-0.

Aftercare

The drain is removed after 48 h. post-operative antibiotics were continued for 2–3 days. Arm sling pouch was used for immobilization of the arm till suture removal in case of fixation with plate and screw and for about a month in cases treated with titanium elastic nail. The patients were allowed for gentle isometric and mobilization exercises after 3 weeks but lifting of heavy weights and overhead abduction were delayed up to 3 months after surgery.

52 (55.32%) out of 94 patients were treated by conservative methods, and 42 (44.68%) were treated by surgical intervention. In that 15 (15.96%) patients were treated by ORIF or closed reduction and internal fixation with titanium elastic intramedullary nail. Notably, 2 cases of fractures treated with TENS required open reduction due to inadequate alignment and difficult closed reduction (Fig. 1). 27(28.72%) cases were treated by ORIF with 3.5 mm plate and screws. The mean follow-up was 8.2 months, ranging from 6 to 13 months. One of our cases of clavicle fracture operated by closed TENS, showed good fracture healing at 6 months (Fig. 2).

The age of the patients ranged from 21 years to 55 years, with a mean of 32.1 years. 68 were male patients and 26 were female patients, showing male preponderance. 50 patients had fracture in the middle one-third, and 44 patients had lateral third fractures. 64 had sustained the fracture following a road traffic accident, and the remaining 30 due to trauma (fall on outstretched hand, assault, direct fall over the shoulder). 72 patients had a fracture of right clavicle, and the remaining 22 had fracture on the left side. 12 patients had open fracture (in the form puncture wound created by sharp spike from fracture end) and were treated by operative methods, 4 cases by titanium elastic intramedullary nail and 8 cases by reconstruction plate and screws. Skin tenting was present in 22 cases and was treated by operative intervention. All 42 patients treated by surgical intervention had displacement of fracture fragments, and shortening of clavicle length of more than 2 cm. Out of 42 patients treated by surgery, 34 (80%) had lateral one-third fractures and 8 had middle third fractures. The clinical criteria of union were lack of tenderness to palpation at the fracture site, no pain at the fracture site, and a full range of motion of the shoulder. The roentgenographic criterion of healing was obliteration of the fracture site by callus, with trabeculae crossing the fracture gap. Based on these criteria, the average time to solid union was 3 months, the range being 2.5–5 months.

Operative group

It took a mean of 9.3 weeks for union with middle third fractures and a mean of 10.2 weeks for fractures of the lateral third treated by operative intervention. The duration of immobilization of the arm was till suture removal (1–2 weeks) in case of fixation with plate and screw and for about a month (3–4 weeks) in cases treated with titanium elastic nail. 2 cases treated by open reduction failed to unite. Both the cases were operated with titanium elastic intramedullary nail. All the fractures treated with plate and screws united in our series. None of the patients treated by operative intervention developed shoulder stiffness. The displacement was corrected, and the clavicular length was maintained, and deformity was not seen in any of these patients. No patients complained of a painful/unsightly scar in our series.Superficial infection was seen in one case operated on with titanium elastic intramedullary nail. One case had outer migration of the nail within 2 weeks following surgery. Two patients operated with plate and screws had prominent metal (plate and screw) causing discomfort, and they underwent removal of implant 1 year following the fixation. Furthermore, one case of recon plating, it was noted that implant breakage at 3-month follow-up X-ray but as healing was good, it was managed without any intervention.

Conservative group

It took a mean of 4.9 weeks for union with middle third fractures and mean of 5.8 weeks for fractures of the lateral third treated by conservative methods (Fig. 3). The duration of immobilization ranged from 4–8 weeks (Mean – 5 weeks) till clinical union.

Non-union was seen in 4(7%) cases, 1 in middle third fracture and 3 in lateral third fractures. In the one case of non-union middle third fracture, the end result was satisfactory as he had no symptoms and had a good range of movements. In the other three case of non-union lateral third fracture, one had a good range of movements and there was no limitation of function, the other two required operative intervention as they had symptomatic non-union. Most of the cases treated by conservative methods were united with a deformity (44 cases – 85%). However, there was no limitation of function attributable to the malunion in these patients.

6 patients treated by conservative methods developed shoulder stiffness after immobilization for 6–8 weeks. 4 of these were lateral third fractures, and 2 were middle third fractures. All cases recovered from shoulder stiffness with good physiotherapy, 12 weeks from the date of fracture.

This study compared the outcomes of conservative versus surgical treatment for clavicle fractures, analyzing 94 patients with midshaft and lateral fractures. Among them, 52 were managed conservatively, while 42 underwent surgical intervention. The results provide important insights into the effectiveness of these approaches and offer comparisons to existing studies in the literature. The average time to complete union in our study was 3 months, with surgical patients experiencing slightly longer healing times (9.3 weeks for middle-third fractures and 10.2 weeks for lateral-third fractures) compared to those treated conservatively (4.9 weeks and 5.8 weeks, respectively). Similar findings were reported by Neer et al. [12], who noted extended recovery periods with surgical fixation due to soft-tissue healing. Despite the longer healing time, the surgical group had a higher union rate, with only two non-union cases (4.76%), both occurring in patients treated with titanium elastic intramedullary nails (TEN). All fractures treated with plates and screws achieved union, which is consistent with Hill et al. [14], who also observed superior union rates in surgically managed fractures compared to non-surgical treatment. The conservative group in our study had a non-union rate of 7.69%, which is slightly higher than the surgical group but falls in line with the literature. Nordqvist et al. [2] reported non-union rates of 6%–8% in patients treated conservatively for clavicle fractures. Similarly, Robinson et al. [16] confirmed that non-union is more common in lateral third fractures managed non-surgically, as observed in our study, where three of four non-unions were in lateral third fractures. A notable outcome in our study was that 85% of patients treated conservatively developed malunion, though it did not result in functional impairments. Nowak et al. [17] have also highlighted that cosmetic deformity is a frequent result of conservative treatment, particularly in midshaft fractures, though this does not always affect function. Our findings align with those of Zlowodzki et al. [18], who suggested that malunion, when properly rehabilitated, may not significantly impact function. In contrast, surgical treatment allowed for the restoration of clavicle alignment and length, with no reported deformities or significant functional deficits. This echoes the findings of the Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society (COTS) [19], which reported better functional outcomes and less deformity in surgically treated patients. In our study, none of the patients who underwent surgery developed shoulder stiffness, whereas six patients (11.54%) in the conservative group experienced stiffness after immobilization. However, these patients recovered with physiotherapy. This pattern of higher stiffness rates in conservatively treated patients has been documented in other studies, such as those by van der Meijden et al. [20]. Among the surgical patients, complications were generally minor but did occur. Two patients treated with TENS experienced issues: one with a superficial infection and the other with nail migration. These complications are in line with reports by Jubel et al. [8], who also noted nail migration in patients treated with TENS for clavicle fractures, underscoring the need for vigilant follow-up. In contrast, patients treated with plates and screws had fewer complications, although two cases (4.76%) experienced discomfort from prominent hardware, requiring implant removal after 1 year. These findings are consistent with Smekal et al. [21], who identified hardware prominence as a frequent reason for secondary procedures following plate fixation. Conservative treatment is often recommended for non-displaced or minimally displaced fractures, but surgical intervention offers clear advantages in cases of displaced or comminuted fractures, especially in lateral third fractures. Our study found that 80.95% of patients treated surgically had lateral third fractures, all of which achieved union with improved functional outcomes. Similar results have been reported by Shen et al. [22], who found that surgical fixation provides better functional and radiological outcomes in displaced lateral third fractures. The risk of non-union and symptomatic malunion is higher in patients treated conservatively, particularly in displaced fractures. This was highlighted in a systematic review by Woltz et al. [23], which supports our findings that surgical intervention results in better outcomes for displaced fractures, although conservative treatment can still be effective for non-displaced cases. In addition, Lazarides and Zafiropoulos noted that surgical treatment reduces the risk of non-union and malunion, which is consistent with our results [24]. It should be noted that our study’s relatively small sample size may limit the generalizability of the findings. Moreover, the mean follow-up period of 8.2 months, though sufficient to assess fracture healing, may not be long enough to evaluate long-term outcomes such as post-traumatic arthritis or other functional impairments. Future research with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods is recommended to fully assess the long-term outcomes of both surgical and conservative treatments. (Table 1).

Our study highlights that while conservative treatment remains a viable option for non-displaced or minimally displaced clavicle fractures, surgical intervention provides significant advantages for displaced fractures, particularly in terms of achieving higher union rates, maintaining anatomical alignment, and improving both functional and cosmetic outcomes. The surgical approach demonstrated not only faster recovery with fewer complications but also greater patient satisfaction due to the prevention of deformity and malunion. This is especially important in cases of lateral third fractures, where conservative management often leads to higher rates of non-union and functional limitations. The findings align with a growing body of evidence emphasizing the superiority of surgical treatment for displaced or comminuted fractures, where the risk of malunion, non-union, and long-term functional impairment is higher with non-operative management. Our results reinforce the need for a personalized treatment strategy based on the fracture’s location, displacement, and patient factors such as activity level and aesthetic concerns. As treatment modalities evolve, future research should aim to further explore long-term functional outcomes, including any residual effects on shoulder mobility, strength, and post-operative quality of life. In addition, studies should assess the cost-effectiveness and potential complications associated with both conservative and surgical approaches over extended follow-up periods. By refining patient selection criteria and optimizing treatment protocols, clinicians can ensure the best possible outcomes for individuals with clavicle fractures.

This study underscores the importance of a personalized approach to treatment, dvocating for surgery in cases of displacement or comminution to minimize complications and enhance patient satisfaction.

References

- 1.Craig EV. Fractures of the clavicle. In: Rockwood CA, Matsen FA, editors. The Shoulder. 3rd ed., Vol. 1. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1990. p. 367-401. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Nordqvist A, Petersson C. The incidence of fractures of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1994;300:127-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Allman FL Jr. Fractures and ligamentous injuries of the clavicle and its articulation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1967;49:774-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Zenni EJ Jr., Krieg JK, Rosen MJ. Open reduction and internal fixation of clavicular fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1981;63:147-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Paffen PJ, Jansen EW. Surgical treatment of clavicular fractures with Kirschner wires: A comparative study. Arch Chir Neerl 1978;30:43-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Siebenmann RP, Spieler U, Arquint A. Rush pin osteosynthesis of the clavicles as an alternative to conservative treatment. Unfallchirurgie 1987;13:303-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Boehme D, Curtis RJ Jr., DeHaan JT, Kay SP, Young DC, Rockwood CA Jr. The treatment of nonunion fractures of the midshaft of the clavicle with an intramedullary Hagie pin and autogenous bone graft. Instr Course Lect 1993;42:283-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Jubel A, Andermahr J, Schiffer G, Tsironis K, Rehm KE. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing of midclavicular fractures with a titanium nail. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;408:279-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Poigenfurst J, Reiler T, Fischer W. Plating of fresh clavicular fractures. Experience with 60 operations. Unfallchirurgie 1988;14:26-37. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Mullaji AB, Jupiter JB. Low-contact dynamic compression plating of the clavicle. Injury 1994;25:41-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Wentz S, Eberhardt C, Leonhard T. Reconstruction plate fixation with bone graft for mid-shaft clavicular non-union in semi-professional athletes. J Orthop Sci 1999;4:269-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Neer CS. Fractures of the clavicle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1960;???:???. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Neer CS, Rockwood CA. Fractures of the shoulder girdle. Shoulder Surg 1984;???:???. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Hill JM, McGuire MH, Crosby LA. Closed treatment of displaced middle-third fractures of the clavicle gives poor results. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997;79:537-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Nordqvist A, Petersson C, Redlund-Johnell I. The natural course of lateral clavicle fracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1998;???:???. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Wakefield AE. Estimating the risk of nonunion following nonoperative treatment of a clavicular fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1359-65. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Nowak J, Holgersson M, Larsson S. Clavicle fractures: Epidemiology, classification, and outcomes. Injury 2000;???:???. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Zlowodzki M, Zelle BA, Cole PA, Jeray K, McKee MD, Evidence-Based Orthopaedic Trauma Working Group. Treatment of acute midshaft clavicle fractures: Systematic review of 2144 fractures: On behalf of the evidence-based orthopaedic trauma working group. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:504-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Canadian Orthopaedic Trauma Society. Nonoperative treatment compared with plate fixation of displaced midshaft clavicular fractures. A multicenter, randomized clinical trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Van Der Meijden OA, Gaskill TR, Millett PJ. Clavicle fractures: A review. Clin Sports Med 2010;???:???. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Smekal V, Oberladstätter J, Struve P, Krappinger D, Kamelger FS, Ebenbichler GR. Plate fixation of midshaft clavicular fractures: A prospective study. Injury 2011;???:???. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Shen WJ, Liu TJ, Shen YS. Plate fixation of fresh displaced midshaft clavicle fractures. Injury 1999;30:497-500. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Woltz S, Stegeman SA, Krijnen P, Van Dijkman BA, Van Thiel TP, Schep NW, et al. Plate fixation compared with nonoperative treatment for displaced midshaft clavicular fractures: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2017;99:106-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Lazarides S, Zafiropoulos G. Conservative treatment of fractures at the middle third of the clavicle: The relevance of shortening and clinical outcome. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2006;15:191-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]