Congenital talipes equinovarus, commonly known as clubfoot, is a prevalent developmental disorder, with pre-natal ultrasound being an effective diagnostic tool that aids in early treatment and better outcomes.

Dr. Gaurav Vatsa, Department of Orthopaedics, Narayan Medical College and Hospital, Sasaram, Bihar, India. E-mail: vatsagaurav07@gmail.com

Introduction: Congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV), or clubfoot, is a common congenital lower limb disorder. Pre-natal diagnosis using ultrasound (US) enables early identification, facilitating timely intervention and improving outcomes. Understanding the diagnostic accuracy and implications of pre-natal CTEV detection is essential for effective clinical management.

Materials and Methods: This observational cohort study evaluated pre-natal US accuracy in detecting CTEV. Two thousand singleton pregnancies between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation were included. Exclusions applied to complicate and multiple pregnancies. Participants underwent anomaly scans, with fetal lower limbs assessed for clubfoot indicators. Follow-up included post-natal examinations and Pirani scoring for confirmed cases. Diagnostic accuracy metrics, including sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values, were calculated.

Results: Among live births, pre-natal US identified CTEV cases, with final confirmation distinguishing structural from positional deformities. The study found high sensitivity and specificity, reinforcing US’s reliability for early detection. All affected cases were successfully treated using the Ponseti method, avoiding surgical intervention. Discussion: Despite its effectiveness, US remains operator-dependent, necessitating standardized protocols to reduce misdiagnosis. Early detection benefits psychological preparedness and treatment planning. Future research should assess long-term functional outcomes and optimize pre-natal screening protocols, particularly in resource-limited settings, to ensure comprehensive CTEV management.

Keywords: Congenital talipes equinovarus, clubfoot, ankle equinus, hindfoot varus, forefoot adductus, midfoot cavus, pre-natal ultrasound.

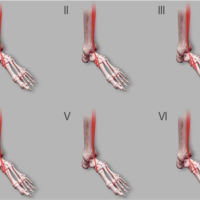

Congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV), commonly known as clubfoot is a prevalent developmental disorder of the lower limb. Its components include ankle equinus, hindfoot varus, forefoot adductus, and midfoot cavus. Ankle equinus involves the ankle being fixed in a downward-pointed position, restricting upward motion. Hindfoot varus is characterized by the heel tilting inward, causing weight to be borne on the outer edge of the foot. The forefoot adductus involves the front part of the foot curving inward, creating a pigeon-toed appearance. Midfoot cavus is marked by an excessively high arch, reducing shock absorption and increasing pressure on the ball and heel of the foot [1]. In low- and middle-income countries, the birth prevalence of CTEV ranges from 0.5 to 2/1,000 live births [2]. Approximately half of the cases affect both feet, which is referred to as bilateral clubfoot. In cases where only one foot is affected, known as unilateral clubfoot, the right foot is more commonly involved than the left. The reasons for this right-side predominance are not entirely understood, but it is a notable pattern observed in clinical practice [3]. In some instances, cases of CTEV have been diagnosed later in gestation, despite initially normal ultrasound (US) findings in earlier scans. This delayed diagnosis suggests that the abnormality may develop later in fetal development. It’s important to note that these cases almost always correspond to CTEV of postural origin. CTEV of postural origin refers to deformities that arise due to the fetus’ positioning within the womb rather than intrinsic structural abnormalities. Factors such as limited space, intrauterine crowding, or the fetus adopting a specific posture can contribute to the development of these deformities. Therefore, while late-diagnosed cases of CTEV may initially present with normal early USs, understanding the distinction between postural and structural origins is essential for guiding clinical management and counseling expectant parents appropriately. Misdiagnosing a structural anomaly like CTEV as a postural deformity could delay necessary treatment, leading to complications and poorer outcomes [4]. At present, US is the only reliable method for pre-natal diagnosis of CTEV. It is the safest and most effective method for diagnosing CTEV pre-natally. Accurate pre-natal diagnosis through US allows parents and healthcare providers to plan for appropriate treatment and management immediately after birth, improving the prognosis for affected infants [5]. However, the role of 3D US in enhancing diagnostic accuracy is not discussed despite its potential advantages in visualizing complex anatomical structures.” Pre-natal diagnosis of CTEV holds significant importance in developing countries, where there has been limited prior research on the condition. Including CTEV diagnosis in routine antenatal anomaly scans can greatly impact the management and prevention of clubfoot in the country by reducing the overall burden of clubfoot-related disabilities in developing countries. Future research initiatives focusing on pre-natal CTEV diagnosis could further advance knowledge, refine screening protocols, and ultimately improve the quality of care provided to affected infants and families nationwide. Herein, we state our report on fetuses with a pre-natal diagnosis of CTEV and a post-natal follow-up to evaluate the precision of US in foretelling the post-natal diagnosis and outcome.

This study follows a cohort design to assess pre-natal diagnosis and outcomes related to CTEV using US. The level of evidence shown here is of Level IV, an observational cohort (descriptive study), that evaluates outcomes based on pre-natal US without any experimental intervention or randomization. 1935 or more samples are needed to have a confidence level of 99.999% that the real value is within ± 1% of the measured value. Hence, 2000 pregnant females between April 2022 and March 2024 were included in the study. The inclusion criterion for this study was singleton pregnancies between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation. Exclusions included complicated pregnancies and multiple pregnancies. Informed consent was obtained from all participants after explaining the purpose and procedures of the study. Participants underwent an anomaly scan between 18 and 24 weeks of gestation. The lower limb of the fetus was specifically examined for signs of clubfoot (CTEV) during these scans. Participants’ progress and outcomes were tracked through pregnancy follow-up notes and newborn records. Women who were lost to follow-up or who underwent treatment at other centers were contacted by telephone to gather information on the pregnancy outcome and any diagnoses made at birth. For stillbirths, obstetric records were reviewed to identify any cases of CTEV. Routine examinations by Orthopedicians at birth were scrutinized to confirm the presence of structural or positional CTEV. Documentation was made on whether the diagnosis of CTEV was established pre-natally or post-natally. The number of affected feet was recorded (unilateral or bilateral). The Pirani score [6], which assesses the severity of clubfoot, was recorded at the initiation of Ponseti treatment [7] in affected children. The data collected were analyzed to determine the accuracy and timing of pre-natal CTEV diagnoses. Data analysis focused on determining the accuracy and timing of pre-natal CTEV diagnoses. Descriptive statistics were employed to summarize demographic characteristics, such as the number of pregnancies, live births, and gender distribution among neonates. The prevalence rate of CTEV was calculated based on live births. Diagnostic performance metrics including sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) were computed to assess the reliability of pre-natal US in detecting CTEV. These metrics were derived from cross-tabulations comparing antenatal US findings with post-natal diagnoses, confirming cases of structural versus positional CTEV.

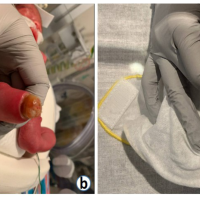

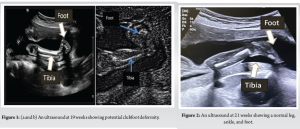

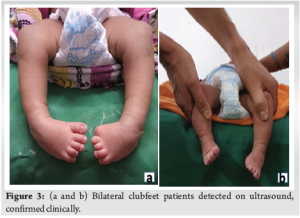

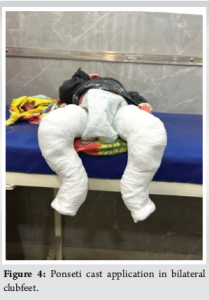

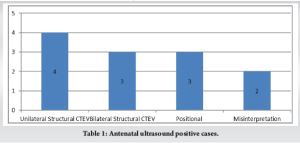

Out of the 2000 pregnancies, there were 1970 live births, with an overall incidence of CTEV at 0.355/100 live births. The median gestational age at the time of US was 19.64 weeks. Fetal anomaly scanning identified CTEV in 12 fetuses pre-natally. (Figure 1 & 2) Upon a review scan after 6 weeks, 2 patients were informed that the initial diagnosis was a misinterpretation, and the fetuses were normal. At birth, 7 cases were confirmed to have structural (bilateral) CTEV, while 3 cases were found to be positional deformities. (Table 1) During the study period, 10 feet were affected by clubfoot, with 3 cases being bilateral (6 feet) (Figure 3) and 4 cases being unilateral (4 feet). Among the neonates, 1039 (52.74%) were male and 931 (47.26%) were female. Post-delivery, all affected feet (10 out of 10) were treated using the Ponseti technique (Figure 4), and no additional open surgeries (posterior or posteromedial release) were performed on any of the patients. With a prevalence of 0.355, out of every 100 live-born infants, approximately 0.355 infants are born with CTEV. This means that in a population of 1,000 live births, approximately 3.55 infants would be expected to have CTEV. The PPV of the screening is 58.33%, meaning that when the test indicates a fetus has CTEV, there is a 58.33% chance that the fetus actually has a structural deformity that will require treatment using the Ponseti method. This indicates that about half of the positive diagnoses made by the US are confirmed as true positives upon further examination. The NPV of the test is 100%, indicating that when the screening test shows no signs of CTEV, it is certain that the fetus does not have the deformity. This high NPV demonstrates the test’s reliability in ruling out CTEV, ensuring no cases are missed. The sensitivity of the test is 100%, which measures the test’s ability to correctly identify all fetuses with CTEV. A sensitivity of 100% means that the screening test detected every case of CTEV, with no false negatives. This ensures that all affected fetuses are identified early. The specificity of the test is 99.75%, which indicates the test’s effectiveness in correctly identifying fetuses without CTEV. A specificity of 99.75% means that the test correctly identified 99.75% of the fetuses that did not have the deformity, with very few false positives.

The sensitivity and specificity of US detection of clubfoot are not extensively documented in the literature. Tillett reported a sensitivity of 0.95, indicating that 95% of affected feet were detected. However, this study involved a small, selected group of patients and was not a comprehensive population survey [8]. Other researchers have suggested that talipes associated with other abnormalities have a very low false positive rate (0%), but when talipes appears isolated, the false positive rate is higher, especially if the US is performed in the third trimester. This variability highlights the need for cautious interpretation of pre-natal US findings in diagnosing isolated clubfoot [9,4]. Another study by Ruzzini et al. indicates that US has a high level of accuracy comparable to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, the US is more cost-effective and non-invasive. While karyotyping can be helpful in excluding other diseases, MRI does not add additional information for diagnosing congenital clubfoot. There is a need for international guidelines for the pre-natal diagnosis of clubfoot, and based on the present review, US appears to be the most appropriate diagnostic method [10]. Despite the high sensitivity and specificity observed in our study, it is important to acknowledge that US remains an operator-dependent modality. Variability in imaging quality and interpretation – stemming from differences in equipment, operator expertise, and technical proficiency – can influence diagnostic accuracy. This operator-dependent variability may lead to false positive or false negative results. False positives can result in unnecessary parental anxiety and potentially unwarranted follow-up, whereas false negatives may delay essential post-natal treatment. Recognizing these factors, there is a pressing need to standardize imaging protocols and enhance training for sonographers to mitigate such variability and ensure consistent diagnostic performance. This study was conducted on 2,000 singleton pregnancies, which may not fully represent diverse populations. The incidence rate of CTEV in the study (0.355 per 100 live births) may differ from global or regional averages due to selection bias or geographic variations. These factors could influence the generalizability of the findings, underscoring the need for larger, more diverse studies to validate the observed results. Pre-natal diagnosis of CTEV, while not altering its in utero progress, is valued by most mothers for its psychological preparedness and potential impact on pregnancy planning [11]. While pre-natal diagnosis may leave some questions unresolved and carries a risk of false positives, it enables early treatment initiation and genetic counseling, with early treatment being the key factor for successful outcomes. The Ponseti method achieves excellent results, with an initial correction rate of around 90% in idiopathic clubfoot cases [7]. The most common cause of relapse is non-compliance with bracing. The present best practice for treating CTEV remains the original Ponseti method, with minimal modifications such as hyperabduction of the foot in the final cast and the necessity for longer-term bracing, up to 4 years. Larger comparative studies are needed before other methods can be recommended [12]. This high level of accuracy in the screening process allows healthcare providers to effectively plan for post-natal treatment and intervention, improving outcomes for affected infants. This study confounds with a study by Faldini et al., which states that pre-natal diagnosis of clubfoot is useful for early detection, parental counseling, and timely treatment at birth, with ultrasonography being the most reliable method despite its dependence on various factors. Although MRI provides high-resolution images that can reveal detailed foot abnormalities, its routine use during pregnancy is approached with caution. This cautious stance stems from the fact that the effects of strong magnetic fields, radiofrequency energy, and acoustic noise on the developing fetus – especially during the critical first trimester – remain insufficiently studied. Moreover, while tissue heating is typically minimal in deeper regions where the fetus resides, there is still concern over exceeding specific absorption rate limits, which could theoretically pose risks. In addition, the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents is generally discouraged, as they cross the placental barrier and have been associated with a slight increase in adverse neonatal outcomes. Therefore, in the absence of robust long-term safety data, MRI in pregnancy should be reserved for situations where the diagnostic benefits clearly outweigh these potential risks [13]. However, although numerous reports support the effective use of US for the pre-natal diagnosis of clubfoot, a systematic review of the literature reveals no clear evidence of a correlation between the timing of the US examination and the severity of the foot malformation. Consequently, US analysis does not provide sufficient information to assist the pediatric orthopedic surgeon in pre-natal counseling [14]. In our view, the primary benefit of pre-natal diagnosis is enabling early treatment initiation, which our studies indicate is a crucial factor in achieving favorable patient outcomes. It can identify patterns and potential relationships between variables, but it does not establish a direct cause-and-effect link, as other underlying factors may influence the observed outcomes. Furthermore, this study does not assess long-term functional outcomes, such as gait abnormalities, deformity recurrence, or the necessity for surgical intervention. Future research should focus on post-treatment follow-up to better understand the impact of early detection and intervention on these critical aspects of CTEV management. In rural areas where there is a lack of services, early treatment may be delayed due to multiple issues (traveling, financial, social), and antenatal diagnosis can help in preparing children for early treatment. While the test is highly reliable in detecting true cases and ruling out false ones, it also highlights the importance of further evaluation and monitoring when a positive diagnosis is made. The pre-natal diagnosis helps in early rectification of deformity and evasion from surgical intervention. However, it is important to note that the findings of this study may not be generalizable to settings where US technology or trained personnel are limited, particularly in remote areas. In addition, the study does not address the post-effectiveness or the feasibility of integrating routine CTEV screening into standard pre-natal care in resource-limited settings.

Prenatal ultrasonography is a highly sensitive and specific modality for the early detection of congenital talipes equinovarus (CTEV). In our cohort, it demonstrated 100% sensitivity, 99.75% specificity, and a perfect negative predictive value, confirming its reliability in ruling out CTEV when not detected. Although the positive predictive value was 58.33%, all confirmed structural cases were effectively treated with the Ponseti method, avoiding the need for surgical intervention. Early prenatal diagnosis allows for timely counseling, psychological preparedness, and planned postnatal care, especially crucial in rural and resource-limited settings. Despite its diagnostic utility, ultrasonography remains operator-dependent, which may lead to false positives and unnecessary parental anxiety. Therefore, standardized imaging protocols and improved sonographer training are essential to enhance diagnostic consistency. While prenatal diagnosis does not influence the intrauterine progression of CTEV, it significantly impacts postnatal outcomes by enabling early initiation of treatment. Our study supports the integration of routine CTEV screening into anomaly scans as a cost-effective measure with considerable clinical value. Further studies involving larger and more diverse populations with long-term post-treatment follow-up are warranted. These should focus on evaluating the functional outcomes of early-detected cases and assessing the practicality of implementing routine screening in low-resource settings.

CTEV, or clubfoot, is a common lower limb disorder that can be identified before birth through US. Early diagnosis allows timely treatment, improving outcomes and reducing complications. The Ponseti method is an effective non-surgical approach for correction. In rural areas, early detection is particularly important to ensure prompt care. Standardized imaging and further research are needed to enhance diagnosis and management.

References

- 1.Miedzybrodzka Z. Congenital talipes equinovarus (clubfoot): A disorder of the foot but not the hand. J Anat 2003;202:37-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Smythe T, Kuper H, Macleod D, Foster A, Lavy C. Birth prevalence of congenital talipes equinovarus in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Trop Med Int Health 2017;22:269-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Kancherla V, Romitti PA, Caspers KM, Puzhankara S, Morcuende JA. Epidemiology of congenital idiopathic talipes equinovarus in Iowa, 1997-2005. Am J Med Genet A 2010;152:1695-700. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Treadwell MC, Stanitski CL, King M. Prenatal sonographic diagnosis of clubfoot: Implications for patient counseling. J Pediatr Orthop 1999;19:8-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Barry M. Prenatal assessment of foot deformity. Early Hum Dev 2005;8:793-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Dyer PJ, Davis N. The role of the pirani scoring system in the management of club foot by the ponseti method. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:1082-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Ponseti IV, Smoley EN. Congenital club foot: The results of treatment. J Bone Joint Surg 1963;45:261-344. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Tillett RL, Fisk NM, Murphy K, Hunt DM. Clinical outcome of congenital talipes equinovarus diagnosed antenatally by ultrasound. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2000;82:876-80. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Shipp TD, Benacerraf BR. The significance of prenatally identified isolated clubfoot: Is amniocentesis indicated. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1998;178:600-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Ruzzini L, De Salvatore S, Longo UG, Marino M, Greco A, Piergentili I, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of clubfoot: Where are we now? Systematic review and meta-analysis. Diagnostics (Basel) 2021;11:2235. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Radler C, Myers AK, Burghardt RD, Arrabal PP, Herzenberg JE, Grill F. Maternal attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis of idiopathic clubfoot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2011;37:658-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Jowett CR, Morcuende JA, Ramachandran M. Management of congenital talipes equinovarus using the Ponseti method: A systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:1160-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Faldini C, Fenga D, Sanzarello I, Nanni M, Traina F, Rosa MA. Prenatal diagnosis of clubfoot: A review of current available methodology. Folia Med (Plovdiv) 2017;59:247-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Rijhsinghani A, Yankowitz J, Kanis AB, Mueller GM, Yankowitz DK, Williamson RA. Antenatal sonographic diagnosis of club foot with particular attention to the implications and outcomes of isolated club foot. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 1998;12:103-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]