Bone mineral density, influenced by lipid profiles and homocysteine levels, may serve as a valuable biomarker for predicting cardiovascular risk in older adults with osteoporosis.

Dr. Ramesh Prasad Agrawal, Department of Microbiology, Government Medical College, Satna, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: drrameshagrawal22@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteoporosis is a prevalent metabolic bone disorder, particularly affecting the elderly, and is often linked to cardiovascular morbidity. This study investigated the associations among osteoporosis, biochemical markers, bone mineral density (BMD), and cardiovascular disease (CVD).

Materials and Methods: A cross-sectional analysis was conducted among 280 individuals diagnosed with osteoporosis and 182 without osteoporosis to assess the relationship between osteoporosis and serum levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), and homocysteine (HCY). Correlations between these biochemical indices and BMD were evaluated. CVD prevalence was compared between osteoporosis and non-osteoporosis groups, and receiver operating characteristic curve analysis was used to assess the predictive potential of BMD for CVD risk.

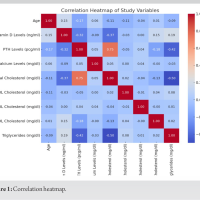

Results: Higher triglyceride, TC, and LDL levels were positively associated with osteoporosis, while elevated HDL and HCY levels showed inverse associations. Triglyceride levels correlated negatively with BMD, whereas TC and HDL demonstrated positive correlations. LDL showed a weak negative association, and HCY exhibited a strong inverse correlation with BMD. Individuals with osteoporosis had lower BMD and a higher incidence of CVD compared to those without osteoporosis. Logistic regression confirmed that reduced BMD significantly increased cardiovascular risk.

Conclusion: This study highlights significant associations among osteoporosis, lipid profiles, HCY levels, BMD, and CVD. The findings suggest that dyslipidemia and altered HCY metabolism may contribute to both bone loss and cardiovascular pathology. BMD may serve as a potential biomarker for identifying individuals at increased cardiovascular risk. Further longitudinal research is needed to establish causal relationships and assess long-term clinical outcomes.

Keywords: Lipid profile, cardiac enzymes, coronary artery disease

Osteoporosis is a systemic metabolic disorder affecting the skeletal system, typified by reduced bone mass, deterioration of trabecular and cortical architecture, and an increased susceptibility to fractures. These skeletal changes manifest clinically as diminished bone mineral content, impaired bone integrity, persistent discomfort, and restricted physical function [1,2]. This condition predominantly impacts individuals in middle and advanced age groups, thereby exerting a substantial burden on the elderly population [3]. Age-related hormonal decline, particularly in gonadal function, disrupts the physiological balance between bone remodeling processes-resorption and formation-thus facilitating the onset of osteoporosis and adversely influencing life quality in aging individuals. Simultaneously, cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions are also widely observed in these demographic cohorts [4]. There is mounting evidence indicating a linkage between senile osteoporosis and vascular diseases, including atherosclerosis, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular events [4]. Notably, osteoporosis has been frequently documented in elderly patients suffering from cerebral infarctions, where alterations in bone turnover markers have shown associations with cerebrovascular pathology [5]. Moreover, shared risk factors such as elevated blood pressure, impaired glucose metabolism, and oxidative damage have been implicated in both reduced bone density and vascular pathologies [5]. It is also worth noting that a significant proportion of older adults with compromised bone mass concurrently present with hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular disorders, suggesting a potential biological or pathophysiological nexus among these conditions [6-8]. Bone mineral density (BMD), a clinical indicator representing the mineral content within bone tissue, serves as the principal diagnostic parameter for identifying osteoporosis. A decline in BMD signifies a loss of skeletal integrity and an elevated likelihood of fracture. Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) remains the benchmark technique for assessing BMD and evaluating fracture susceptibility [5]. Several modifiable and non-modifiable risk factors are common to both osteoporosis and cardiovascular conditions, including senescence, tobacco use, sedentary behavior, and inadequate vitamin D status [6]. Hypothesized biological mechanisms connecting these two pathologies include endothelial damage, systemic inflammatory responses, and the activity of bone-related hormones such as osteocalcin [7]. Despite the observed associations between diminished bone mass and cardiovascular morbidity [5], the underlying interplay between serum biomarkers, skeletal density, and cardiovascular prognosis has yet to be fully delineated. Park et al. [9] and Hu et al. [10] emphasized the necessity for further investigations to elucidate the prognostic relevance of bone density measurements in anticipating cardiovascular risks. Nonetheless, there remains a paucity of robust clinical trials and comprehensive datasets to substantiate this connection definitively. Therefore, the central aim of the present study is to investigate the association and clinical relevance of osteoporosis and its related bone metabolism indices with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease markers in older populations.

Study population

A retrospective review was conducted involving clinical records at our institution, encompassing data collected between July 2021 and January 2024. The cohort comprised 280 individuals diagnosed with osteoporosis and 182 without osteoporosis. BMD assessments were performed for all participants using DXA. Based on the BMD results, subjects were stratified into two categories: those with osteoporosis and those without. The research adhered to the ethical standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki [11].

Inclusion criteria

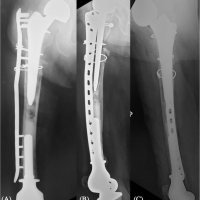

Participants were eligible for inclusion if they had complete clinical data, demonstrated a high degree of compliance, and possessed intact cognitive function, as indicated by a Mini-Mental State Examination score of 24 or above. BMD was assessed using a DXA scanner, with measurements taken at the lumbar spine (L1–L4), femoral neck, Ward’s triangle, and femoral trochanter. The diagnostic thresholds followed the World Health Organization guidelines, categorizing individuals with a T-score ≥ −1.0 as having normal bone mass, those between −1.0 and −2.5 as having osteopenia, and those with a T-score ≤ −2.5 as osteoporotic [12]. Coronary artery disease (CAD) was diagnosed based on clinical manifestations, electrocardiographic findings, and elevated cardiac enzymes. Hypertension was defined by a systolic pressure of at least 140 mmHg and/or a diastolic pressure of 90 mmHg or higher. Cerebral infarction diagnosis required supportive clinical features and imaging evidence from computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging, while excluding hemorrhagic lesions or alternative causes.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded if they had underlying thyroid or parathyroid disorders, renal tubular or glomerular diseases, diabetes mellitus, chronic liver disease, bone tumors or metastases, or a history of gastrointestinal surgery. Additional exclusion criteria included the presence of severe systemic illnesses affecting hepatic, renal, or endocrine function related to bone metabolism, present or recent use (within 1 year) of medications that influence bone turnover such as corticosteroids or other hormonal therapies, and any psychiatric illness that interfered with normal communication or comprehension.

Evaluation methods and parameters

Patient demographic and clinical data-including sex, age, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure (DBP), and fasting blood glucose (FBG)-were systematically recorded. Venous blood samples (3 mL) were obtained from each participant following an overnight fast. These samples were centrifuged at 3,000 revolutions/min for 10 min to isolate the serum, which was then analyzed for triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), calcium (Ca), and homocysteine (HCY) levels using an automated biochemical analyzer. BMD was measured using DXA in the supine position. The anatomical regions assessed included the lumbar spine (L1–L4), femoral neck, Ward’s region, and the femoral trochanter.

Statistical analysis

All statistical procedures were performed using statistical software package (SPSS) version 20.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square-test, while continuous variables were examined using the independent sample t-test. Data were presented as number and percentage (n [%]) for categorical variables and as mean ± standard deviation (x̄ ± s) for continuous variables. Pearson correlation analysis and multivariate logistic regression modeling were employed to identify potential risk factors associated with osteoporosis in the elderly population. A P < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

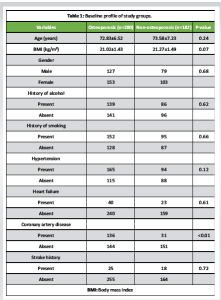

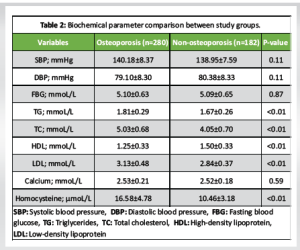

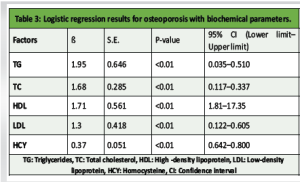

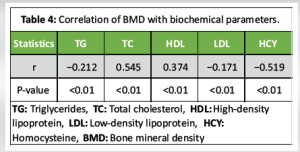

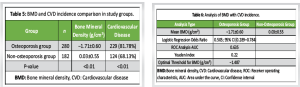

The baseline characteristics of the participants are presented in Table 1. There were no statistically significant differences in age, BMI, or gender distribution between individuals with and without osteoporosis. The prevalence of hypertension, heart failure, stroke history, smoking, and alcohol consumption was comparable between the groups, indicating that these comorbid factors were well-matched. However, the prevalence of CAD was significantly higher in the osteoporosis group compared to the non-osteoporotic group (P < 0.01), suggesting a possible association between osteoporosis and cardiovascular comorbidity. Biochemical parameters assessed across the groups are summarized in Table 2. While systolic and DBPs, FBG levels, and serum Ca showed no significant intergroup differences, the osteoporosis group demonstrated significantly elevated levels of TG, TC, LDL, and HCY, alongside significantly reduced HDL levels (all P < 0.01). These findings indicate a more atherogenic biochemical profile in individuals with osteoporosis. The logistic regression analysis in Table 3 identified TG, TC, HDL, LDL, and HCY as significant predictors of osteoporosis. Notably, the odds of osteoporosis increased with higher TG, TC, LDL, and HCY levels, while lower HDL levels were associated with higher osteoporosis risk. All biochemical markers included in the model showed statistically significant associations (P < 0.01), highlighting their potential role in osteoporosis pathophysiology. Correlation analysis between BMD and selected biochemical markers, as shown in Table 4, revealed statistically significant relationships. BMD was inversely correlated with TG, LDL, and HCY levels while showing positive correlations with TC and HDL levels (all P < 0.01). These associations underscore the complex interplay between lipid metabolism, HCY levels, and bone health. Table 5 compares BMD and cardiovascular disease (CVD) prevalence between the groups. The osteoporosis group exhibited significantly lower mean BMD and a higher incidence of CVD (P < 0.01 for both), suggesting a concurrent deterioration in skeletal and cardiovascular health. Further analysis of BMD in relation to CVD, as presented in Table 6, revealed a significant predictive value of BMD for CVD. Logistic regression indicated an odds ratio of 0.505 (95% confidence interval: 0.289–0.784), implying that lower BMD is associated with higher odds of CVD. The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis demonstrated an area under the curve of 0.635, with a Youden Index of 0.22. The optimal BMD threshold for predicting CVD was determined to be −1.487 g/cm².

Our study identified notable associations between osteoporosis and various biochemical parameters. In the logistic regression analysis, elevated triglyceride, TC, and LDL levels were positively correlated with the presence of osteoporosis. In contrast, higher levels of HDL and HCY showed an inverse relationship with osteoporosis. TG were negatively correlated with BMD, while TC and HDL levels were positively correlated. LDL showed a weak negative correlation with BMD, and HCY demonstrated a strong negative correlation. These observations imply that lipid profiles and HCY are important factors influencing bone health. In addition, we found significant differences in both BMD and the prevalence of CVD between the osteoporosis and non-osteoporosis groups. The osteoporosis group exhibited significantly lower BMD and a higher incidence of CVD compared to the non-osteoporosis group. This suggests a potential link between osteoporosis and increased cardiovascular risk. Further regression and correlation analyses between BMD and CVD incidence revealed a significant positive relationship. To evaluate the diagnostic utility of BMD for identifying CVD risk, we conducted ROC analysis which highlighted the potential value of BMD as a diagnostic tool for identifying individuals at increased risk of CVD. Although the exact mechanisms linking osteoporosis, biochemical markers, BMD, and CVD require further exploration, our study provides valuable preliminary insights into these interconnections. One potential mechanism is that blood lipids, as key fatty components of atherosclerotic plaques, may inhibit the binding of plasminogen to platelets, hindering fibrinolysis and promoting thrombosis, which could lead to cardiovascular and cerebrovascular conditions [13]. In addition, lipid oxidation products are implicated in the formation of atherosclerosis, which could impair osteoblast differentiation. In older individuals, who often experience increased pulse pressure and pronounced atherosclerosis, vascular nitric oxide, important for bone remodeling, is reduced due to endothelial damage during atherosclerosis [14]. HCY, a sulfur-containing amino acid involved in methionine and cysteine metabolism, has been established as a risk factor for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Abnormal HCY levels contribute to arteriosclerosis, and in conjunction with hypertension, they increase the risk of cerebral arteriosclerosis, transient ischemic attacks, stroke, and hemorrhage. Previous studies [15] have shown that elevated HCY levels degrade the extracellular matrix through metalloproteinases, reduce bone blood flow, and contribute to bone disease through oxidative stress mechanisms. Our study found that the osteoporosis group had significantly higher HCY levels than the non-osteoporosis group (P < 0.05). BMD T-scores correlated with HCY levels, suggesting that HCY could be an important biomarker for assessing cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in conjunction with osteoporosis. Osteoporosis, a prevalent degenerative disease in the elderly, is difficult to reverse once significant bone loss occurs [16]. It is vital for individuals, particularly those with hypertension, CAD, and cerebral infarction, to actively manage their health. This includes early detection and intervention of potential issues, timely treatment for emerging symptoms, and proactive measures to prevent osteoporosis. Managing blood pressure, controlling blood lipids, and monitoring other relevant biochemical markers are essential for both cardiovascular and cerebrovascular health, as well as for preventing bone mass loss [17]. For patients with hypertension, thiazide diuretics have been shown to reduce Ca excretion and help preserve bone density [15]. Optimizing vitamin D levels also benefits both bone and cardiovascular health [6,18]. Screening for osteoporosis should be considered in hypertensive patients to enable early detection and management. Furthermore, healthcare professionals should prioritize osteoporosis screening, provide educational resources, and counsel patients with cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases on prevention strategies, as this is crucial for early intervention and control [19]. It is important to note that the present study is cross-sectional, limiting our ability to establish causality or predict long-term outcomes. Future longitudinal studies are necessary to confirm our findings and explore the temporal relationships between osteoporosis, biochemical markers, BMD, and CVDs. Investigating the underlying mechanisms connecting these factors will provide deeper insights into the pathophysiology of both osteoporosis and CVD, as well as potential therapeutic strategies. In addition, confounding factors such as age, sex, smoking, and medication use should be considered in future longitudinal studies to clarify the relationships between these parameters. Research should also focus on the role of BMD as a diagnostic tool for identifying individuals at heightened cardiovascular risk, as well as the specific biomarkers and therapeutic targets involved.

The findings of this study underscore a significant correlation between osteoporosis, biochemical parameters, BMD, and cardiovascular pathology. Altered serum lipid concentrations and elevated HCY levels appear to play a contributory role in the onset of osteoporosis. Moreover, a decline in BMD, particularly among osteoporotic individuals, is associated with an elevated likelihood of developing cardiovascular conditions. These observations highlight the potential utility of BMD assessment as a predictive indicator for cardiovascular risk. Nevertheless, further investigations are essential to better understand the pathophysiological pathways involved and to clarify the clinical relevance of these associations.

This study highlights a significant clinical overlap between osteoporosis and CVD in older adults, with reduced BMD correlating with dyslipidemia and elevated HCY levels. These shared biochemical pathways suggest that BMD assessment can serve not only as a diagnostic tool for osteoporosis but also as a potential marker for cardiovascular risk. Clinicians should adopt a holistic approach, incorporating BMD evaluation and lipid/ HCY profiling into routine assessments for elderly patients, particularly those with existing cardiovascular conditions. Early identification and integrated management may aid in preventing both skeletal and cardiovascular complications, improving overall patient outcomes.

References

- 1.Bover J, Ureña Torres P, Torregrosa JV, Rodríguez-García M, Castro-Alonso C, Górriz JL, et al. Osteoporosis, bone mineral density and CKD-MBD complex (I): Diagnostic considerations. Nefrologia (Engl Ed) 2018;38:476-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Chen X, He B, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Zhao L. Investigating the effect of history of fractures and hypertension on the risk of all-cause death from osteoporosis: A retrospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2023;102:e33342. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Peng Z, Tao S, Liu Y, Sun P, Gong L, Bai Y, et al. Analysis on the correlation between the occurrence of vertebral artery ostium stenosis and the severity of osteoporosis in elderly patients with atherosclerosis. Acta Orthop Belg 2022;88:685-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Sheets KM, Buzkova P, Chen Z, Carbone LD, Cauley JA, Barzilay JI, et al. Association of covert brain infarcts and white matter hyperintensities with risk of hip fracture in older adults: The cardiovascular health study. Osteoporos Int 2023;34:91-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Pineda-Moncusí M, El-Hussein L, Delmestri A, Cooper C, Moayyeri A, Libanati C, et al. Estimating the incidence and key risk factors of cardiovascular disease in patients at high risk of imminent fracture using routinely collected real-world data from the UK. J Bone Miner Res 2022;37:1986-96. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Park JM, Lee B, Kim YS, Hong KW, Park YC, Shin DH, et al. Calcium supplementation, risk of cardiovascular diseases, and mortality: A real-world study of the Korean national health insurance service data. Nutrients 2022;14:2538. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Ruediger SL, Koep JL, Keating SE, Pizzey FK, Coombes JS, Bailey TG. Effect of menopause on cerebral artery blood flow velocity and cerebrovascular reactivity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Maturitas 2021;148:24-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Zhu B, Yang J, Zhou Z, Ling X, Cheng N, Wang Z, et al. Total bone mineral density is inversely associated with stroke: A family osteoporosis cohort study in rural China. QJM 2022;115:228-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Park JH, Dehaini D, Zhou J, Holay M, Fang RH, Zhang L. Biomimetic nanoparticle technology for cardiovascular disease detection and treatment. Nanoscale Horiz 2020;5:25-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Hu X, Ma S, Chen L, Tian C, Wang W. Association between osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease in elderly people: Evidence from a retrospective study. PeerJ 2023;11:e16546. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.World Medical Association. World medical association declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.World Health Organization (WHO). Consensus development conference: Diagnosis, prophylaxis, and treatment of osteoporosis. Am J Med 1993;94:646-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Hu X, Ma S, Yang C, Wang W, Chen L. Relationship between senile osteoporosis and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases. Exp Ther Med 2019;17:4417-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Zhu J, Guo F, Zhang J, Mu C. Relationship between carotid or coronary artery calcification and osteoporosis in the elderly. Minerva Med 2019;110:12-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Martí-Carvajal AJ, Solà I, Lathyris D, Salanti G. Homocysteine lowering interventions for preventing cardiovascular events. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;4:CD006612. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Syu DK, Hsu SH, Yeh PC, Kuo YF, Huang YC, Jiang CC, et al. The association between coronary artery disease and osteoporosis: A population-based longitudinal study in Taiwan. Arch Osteoporos 2022;17:91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Gilbert ZA, Muller A, Leibowitz JA, Kesselman MM. Osteoporosis prevention and treatment: The risk of comorbid cardiovascular events in postmenopausal women. Cureus 2022;14:e24117. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Cipriani A, Dall’Aglio PB, Mazzotta L, Sirico D, Sarris G, Hazekamp M, et al. Diagnostic yield of non-invasive testing in patients with anomalous aortic origin of coronary arteries: A multicentric experience. Congenit Heart Dis 2022;17:375-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Tang L, Hu H, Zhou Y, Huang Y, Wang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Expression and clinical significance of ACTA2 in osteosarcoma tissue. Oncologie 2022;24:913-25. [Google Scholar | PubMed]