This case highlights the importance of early diagnosis and surgical intervention in cervical spine injuries. An 18-year-old male with a C4-C5 fracture and neurological deficits underwent cervical discectomy and fusion, resulting in significant neurological improvement. The case underscores that timely decompression and stabilization, combined with focused rehabilitation, can lead to substantial recovery, especially in young patients.

Dr. N. Prashanth, Department of Orthopaedics, PSP Medical College and Hospital, Tambaram, Kancheepuram, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: nprashanth098@gmail.com

Introduction: Cervical spine fractures, particularly those at C4 and C5, are among the most serious forms of spinal injuries due to the involvement of the cervical spinal cord, which regulates motor and sensory pathways throughout the body.

Case Report: This report presents an 18-year-old male who sustained fractures at the C4 and C5 levels after a traumatic fall, resulting in complete motor loss (0/5) and partial sensation (1/2) in both upper and lower limbs. Following posterior decompression and stabilization from C3 to C5, his neurological function improved: upper limb strength increased to 3/5, lower limb strength to 1/5, and sensory function was fully restored in both limbs (2/2).

Conclusion: This case highlights the potential for recovery after timely surgical intervention in severe cervical spine injuries.

Keywords: C4-C5 fracture, decompression, spinal stabilization, neurological recovery, cervical spine trauma.

Cervical spine fractures, particularly those at C4 and C5, are among the most serious forms of spinal injuries due to the involvement of the cervical spinal cord, which regulates motor and sensory pathways throughout the body. Injuries to this region, frequently seen after high-energy trauma in young adults, can result in paralysis or severe disability without appropriate intervention (Fehlings et al. 2017) [1]. Approximately 40% of affected individuals experience neurological deficits, and around 10% of traumatic spinal cord injuries do not show clear radiographic evidence. The initial management strategy emphasizes early detection, immobilization, and stabilization to protect spinal cord function. Surgical decompression and stabilization are critical in relieving spinal cord compression and enhancing the potential for neurological recovery (Wilson et al., 2012) [2]. This case illustrates the management and outcome of a young patient who underwent posterior decompression and stabilization for a traumatic cervical spine injury.

The patient, an 18-year-old male, presented to the emergency department following a fall from height. Initial evaluation revealed profound neurological deficits, including complete motor paralysis (0/5 power) and diminished sensation (1/2) in both upper and lower limbs. A computed tomography scan identified fractures at C4 and C5, with spinal canal narrowing and associated spinal cord compression. Magnetic resonance imaging confirmed spinal cord edema at the injury site, indicating the potential for reversible spinal cord damage if promptly addressed (Karsy et al., 2018) [3]. Based on these findings, urgent surgical intervention was recommended.

Preoperative Neurological Evaluation

Upon examination, the patient exhibited complete motor loss (0/5) and reduced sensation (1/2) in both limbs, with absent reflexes below the injury level and loss of bowel and bladder control. These findings suggested a complete cervical spinal cord injury at C4–C5, with a high risk of lasting impairment. The patient was prepared for emergency surgery to reduce further spinal cord damage and improve the chances of neurological recovery (Fehlings et al., 2012) [1].

Pre-operative – (Fig. 1 and 2)

Treatment

The surgical team performed a posterior decompression and stabilization from C3 to C5, a preferred approach for addressing multi-level compression injuries involving cervical spinal fractures. A laminectomy at C4 and C5 was conducted to relieve spinal cord compression, and pedicle screws and rods were placed from C3 to C5 for stabilization. This approach provided the necessary support to reduce the risk of further spinal cord injury and promote neurological recovery. Post-operatively, the patient was managed with neuroprotective strategies, including corticosteroids, to control inflammation and spinal immobilization to support healing (Liu and Li, 2020) [4].

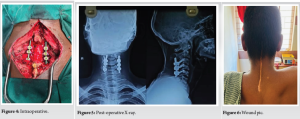

Intraoperative – (Fig. 3 and 4)

Post-operative X-ray – (Fig. 5)

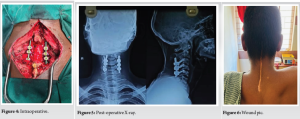

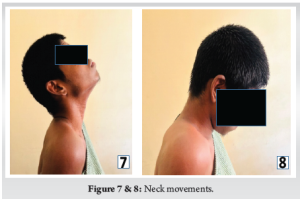

Following surgery, the patient showed notable neurological improvement. Upper limb motor function improved to 3/5, while lower limb strength increased to 1/5. Sensory function returned to normal (2/2) in both the upper and lower limbs. The patient was then enrolled in an intensive rehabilitation program, focusing on physical therapy to further enhance motor function, maintain joint mobility, and prevent complications such as muscle atrophy and pressure sores (Tator et al., 2019) [5].

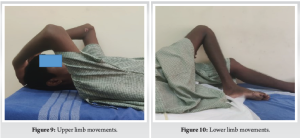

Final Follow-up – (Fig. 6-10)

Outcome

At the latest follow-up, the patient exhibited significant neurological improvement. Motor power in the upper limbs improved to 3/5, with complete sensory recovery graded at 5/5. In the lower limbs, motor strength also progressed to 3/5, and sensation was fully restored to 5/5. Functionally, the patient was able to perform most daily activities independently, with ongoing rehabilitation aimed at further strengthening lower limb function and enhancing mobility. The overall outcome indicated substantial recovery following early decompression and stabilization.

Injuries to the cervical spine, especially at the C4 and C5 levels, can lead to significant neurological deficits that may become permanent if not managed urgently. It was generally accepted that the most injured spinal level is at the 5th and 6‑ cervical vertebrae, as this level has the greatest range of flexion or extension stress and therefore most susceptible to trauma. Between 2001 and 2004 study conducted by Shrestha et al. showed 60% of cases were due to fall from height in a series of 149 patients with cervical spine injuries like our case [6]. Flexion–distraction type of violence was more common in subaxial cervical spine injuries, as these injuries cause facet sprains, facet dislocations, jumped facets, or perched facets [7]. The treatment of cervical spine fractures and dislocations has several goals, including reduction of the deformity and early rehabilitation. The choice of treatment modality is based on the anatomy of the fractures and the experience of the surgeon [8]. Literature supports that early decompression surgery – ideally within 24 h – can mitigate secondary damage from edema, ischemia, and inflammation, which contribute to worsened outcomes in spinal cord injuries [1,2]. This patient’s positive response to surgery, particularly the regained sensation and partial motor recovery, aligns with evidence suggesting that early decompression can improve outcomes even in severe injuries. The posterior approach was effective for stabilizing the multi-level cervical injury, supporting similar findings that recommend this technique when extensive decompression is needed across several vertebral levels [4]. Young patients often have a greater capacity for neurological recovery due to neuroplasticity, which may further contribute to improved outcomes when early and comprehensive management is provided. The role of timing of surgical intervention in spinal cord injury remains one of the most important topics. Despite immense research efforts related to spinal cord injury treatment, neurological recovery and overall outcome remains poor. Research using models has provided evidence that early decompression surgery can lead to improved neurological recovery [9]. In our study, the progression of neurological recovery was more in patients underwent early surgical intervention. Hence, early surgical intervention still offers hope [10]. Pressure sore is one of the known complications of cervical spine injuries. Stal et al. cited a 20% incidence in paraplegic patients and a 26% incidence on patients who are quadriplegic. In my report, my patient develops grade II pressure sore, which was managed with repeated debridement and antibiotics [11,12]. The combination of early surgery and intensive post-operative rehabilitation can significantly impact recovery, as shown in this case, highlighting the value of a coordinated, multidisciplinary approach to care.

This case underscores the importance of prompt surgical intervention in young patients with severe cervical spine injuries. Posterior decompression and stabilization facilitated partial neurological recovery and improved the patient’s sensory and motor function. Early intervention combined with intensive rehabilitation shows promise in optimizing outcomes and reducing long-term disability in young individuals with high cervical fractures.

Injuries to the cervical spine, especially at the C4 and C5 levels, can lead to significant neurological deficits that may become permanent if not managed urgently. Literature supports that early decompression surgery – ideally within 24 h – can mitigate secondary damage from edema, ischemia, and inflammation, which contribute to worsened outcomes in spinal cord injuries.

References

- 1.Fehlings MG, Tetreault LA, Wilson JR, Kwon BK. Management of cervical spine injuries: Evidence-based approaches and emerging therapies. J Spinal Cord Med 2017;40:557-69. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Wilson JR, Singh A, Craven C, Verrier MC, Drew B, Ahn H, et al. Early versus late surgery for traumatic spinal cord injury: The results of a prospective Canadian cohort study. J Neurotrauma 2012;29:2341-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Karsy M, Hawryluk G, Lau D, Mummaneni PV. Timing of decompression in spinal cord injury. Neurosurg Clin North Am 2018;29:131-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Liu X, Li Y. The role of posterior decompression and fixation in the treatment of cervical spine injuries with cord compression. Spine Surg J 2020;15:95-104. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Tator CH, Fehlings MG, Kerr D. Spinal cord injury rehabilitation and recovery. Spinal Cord Series Cases 2019;5:92. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Shreshtha D, Carg M, Singh GK, Singh MP, Sharma UK. Cervical spine injuries in a teaching hospital of eastern region of Nepal: A clinico-epidemiological study. Department of orthopaedics BP koirala institute of health sciences dharan Nepal. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc 2007;46:107-11. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Radcliff K, Benjamin G, Thomasson DO. Flexion-distraction injuries of the subaxial cervical spine. Semin Spine Surg 2015;25:45-56. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Dvorak MF, Fisher CG, Fehlings MG, Rampersaud YR, Oner FC, Aarabi B, et al. The surgical approach to subaxial cervical spine injuries: An evidence-based algorithm based on the SLIC classification system. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2620-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Vaccaro AR, Daugherty RT, Sheehan TP, Dante SJ, Cotler JM, Balderston RA, et al. Neurologic outcome of early versus late surgery for cervical spinal cord injury. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:2609-13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Chandwani V, Ch BK, Ch AC, Kaif M, Vishwanath GU. Subaxial (C3-C7) cervical spine injuries: Comparison of early and late surgical intervention. Indian J Neurotrauma 2010;7:145-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Burns SP, Golding DG, Rolle WA Jr., Graziani V, Ditunno JF Jr. Recovery of ambulation in motor-incomplete tetraplegia. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1997;78:1169-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Bauer JD, Mancoll JS, Phillips LG. Pressure Sores. Cha. 74. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott-Raven; 2024. [Google Scholar | PubMed]