Local infiltration analgesia using a combination of Bupivacaine and Fentanyl in total hip arthroplasty offers significantly superior postoperative pain relief, reduced analgesic requirements, fewer complications, and a shorter hospital stay compared to the combination of bupivacaine and ketorolac.

Dr. Sanjeev Chincholi, Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: chincholi1969@gmail.com

Introduction: Local infiltration analgesia (LIA) has been reported as a viable option to tackle postoperative pain. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs such as ketorolac and opioids such as fentanyl have shown promising results in the past. At the same time, there are other studies which has refuted any benefit of LIA in postoperative pain management. The presence of conflicting reports without any consensus on the best combination for LIA necessitates further research, and hence we conducted a triple-blinded randomized controlled trial to compare the efficacy of ketorolac and fentanyl in reducing post-operative pain when administered through LIA.

Materials and Methods: This triple-blind randomized control trial was conducted on 90 consenting patients undergoing elective primary THA after obtaining institutional ethical approval. Patients were randomized into three groups (n = 30 each). Group A received LIA with Bupivacaine and fentanyl, Group B received bupivacaine and ketorolac, and Group C received normal saline. Postoperative pain was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively. Secondary outcomes included total analgesic consumption, time to ambulation, length of hospital stay, and incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting.

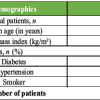

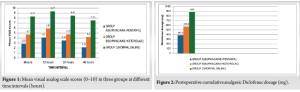

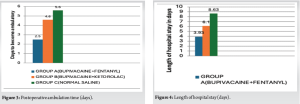

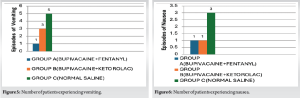

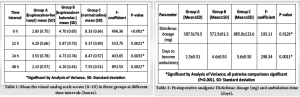

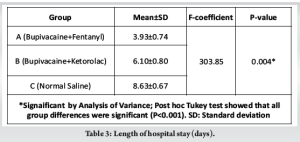

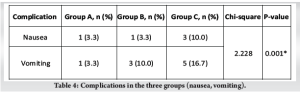

Results: Group A (Bupivacaine + Fentanyl) patients demonstrated significantly lower mean VAS pain scores at all time points compared to Group B (Bupivacaine + Ketorolac) and Group C (Normal Saline) (P < 0.05). The mean hospital stay was shortest in Group A (3.93 ± 0.74 days), with significant differences among all groups (P < 0.05). Total mean postoperative diclofenac consumption was lowest in Group A (387.5 ± 76.5 mg), and earlier ambulation was observed in Group A (2.5 ± 0.51 days) as compared to those in other groups (P < 0.05). The incidence of postoperative nausea and vomiting was also lowest in Group A (3.3%) compared to Groups B and C (P = 0.001).

Conclusion: LIA with fentanyl provides superior postoperative analgesia compared to ketorolac in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty, resulting in better pain control, reduced rescue analgesic use, earlier ambulation, shorter hospital stay, and lower incidence of nausea and vomiting.

Keywords: Local infiltration analgesia, periarticular injection, fentanyl, bupivacaine, ketorolac, total hip arthroplasty.

Controlling post-operative pain remains a significant challenge for surgeons, and the inability to manage it effectively can lead to various complications. Poorly controlled pain may impair organ function, delay early rehabilitation, and reduce patient satisfaction, ultimately resulting in decreased functional outcomes [1,2]. Inadequate physiotherapy and prolonged pain management can increase the length of hospital stay and, in severe cases, contribute to cardiovascular complications over time. Various analgesic modalities have been developed, including oral, intravenous (IV), intrathecal, nerve blocks, and local infiltration techniques [3]. Local infiltration analgesia (LIA) was first described by Kerr and Kohan using Ropivacaine, ketorolac, and adrenaline with promising results [4]. Since then, numerous modifications and trials have been conducted to optimize drug combinations for LIA [4-7]. The agents tested in these studies are broadly categorized into non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids. Fentanyl in particular, has been combined with bupivacaine in total knee arthroplasty, and has demonstrated reduced pain scores and better functional outcomes [6,8] However, a few studies have questioned the efficacy of LIA, suggesting that it may not be a significantly better alternative to other analgesic techniques [9]. The presence of conflicting reports without any consensus on the best combination for LIA necessitates further research, and hence we conducted a triple-blinded randomized controlled trial to compare the efficacy of ketorolac and fentanyl in reducing post-operative pain when administered through LIA.

A prospective study was conducted over 18 months from December 2023 to June 2025 in a territory care center of North India. The ethical approval from the Institutional Ethics Board was taken, and written informed consent was obtained from all study participants. A sample size of 90 was calculated assuming a 95% confidence interval and an 80% power level using the following formula. n = Samples in each group, x1 = mean of the variable group 1, x2 = mean of the variable group 2, σ1 = standard deviation of the variables in group 1, σ2 = standard deviation of the variables in group 2, value of the normal deviate at considered level of confidence (for two sided test), z1−β = value of the normal deviate at considered power of study (for two sided test) 0.35, =0.59, σ1=0.31, σ2=0.28, 1.96 at 95% confidence internal 0.84 at 80% power of file study n = [(0.31)2 + (0.28)2] × (1.96 + 0.84)2/(0.35−0.59)2 = 24 in each group

To generalize the result, a total of 30 patients were taken in each group.

A total of 90 patients undergoing elective primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) were enrolled in the study. The consenting patients aged between 18 and 80 years undergoing primary THA for avascular necrosis of the femoral head, primary and secondary osteoarthritis due to sequelae of septic hip, healed tuberculosis, and post traumatic arthritis were included. Patients undergoing second-stage THA or THA for recent traumatic injury were excluded. Patients with a history of low backache, neurological or psychological disorders, drug dependence or allergy to study drugs, and hepatic or renal insufficiency were also excluded.

All enrolled patients were randomly allocated by one investigator into three groups A, B, and C (n = 30 each) using a computer-generated sequence. All patients were operated under spinal anaesthesia at a single center by same senior arthroplasty surgeon. All cases were operated in lateral position using a posterior approach to the hip joint, and implants of same brand were used. Following femoral component insertion, before reduction of the hip joint, 100 mL the respective drug mixtures were injected into the periarticular tissues around the posterior and anterior capsules, subcutaneous fat, and the layer beneath the subcuticular skin. Neither the operating surgeon nor the participants were informed if they were getting Fentanyl or Ketorolac, or Placebo (NS). Furthermore, to ensure methodological rigor and eliminate bias, the data collectors and data analysts were also blinded to the group assignments so they did not know if they were analyzing the data of a control group or a case group. Group A (Fentanyl group) received a periarticular injection containing 20 mL bupivacaine (0.5%) + 2 mL Fentanyl (100 μm) +78 mL Normal Saline. Group B (Ketorolac group) received 20 mL Bupivacaine (0.5%) + 1 mL Ketorolac (30 mg) +79 mL Normal Saline. Group C (control group) received 100 mL normal saline alone. Postoperative protocol was the same for all the patients, irrespective of their group. Patients were observed in the orthopedic ward, and vital monitoring was done. All patients routinely received second-generation cephalosporin and Diclofenac 75 mg IV every 12 h. Pain was assessed using the visual analog scale (VAS) at 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively. Additional diclofenac was offered to the patients if they experienced and complained about the pain, and the dosages were recorded by the nursing staff. If needed, Tramadol IV was given to manage the pain not responding to the Diclofenac. Additional outcomes such as total postoperative analgesic consumption, time to ambulation, length of hospital stay, and incidence of postoperative nausea or vomiting were also recorded by independent data collectors. Data were compiled in Microsoft Excel for further analysis.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using analysis of variance. Categorical variables were presented as numbers and percentages, with comparisons made using the Chi-square test. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data were compiled in Microsoft Excel 2024 and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 20.0.

It was observed that the Group A (Bupivacaine + Fentanyl) had statistically significant lower mean VAS scores as compared to Group B (Bupivacaine + Ketorolac) and Group C (Normal Saline) at all-time intervals of 6, 12, 24, and 48 h postoperatively (Table 1 and Fig. 1) (P < 0.05). Post hoc Tukey analysis further confirmed that all pairwise comparisons between groups were significant (P < 0.001), indicating superior analgesic efficacy of the combination used in the fentanyl Group. Furthermore, patients in Group A (Bupivacaine + Fentanyl) required significantly less cumulative dosage of diclofenac (Mean: 387.5 ± 76.5 mg) as compared to patients in ketorolac group (Mean: 572.5 ± 91.3) and control group (Mean: 885.0 ± 123.6) (F-coefficient 193.11, P < 0.05, Table 2 and Fig. 2). Patients in fentanyl group required significantly less mean number of days to become ambulatory (2.5 ± 0.51 days) as compared to bupivacaine Group (4.6 ± 0.50 days) and control group (5.6 ± 0.50 days) (F-coefficient 298.34, P < 0.05, Table 2 and Fig. 3). Post hoc analysis further confirmed the pairwise differences which was found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001). These findings indicated better postoperative pain control and faster recovery in group fentanyl. Apart from this, hospital stay was also significantly less in Group A (Bupivacaine + Fentanyl) with the shortest mean hospital stay of 3.93 ± 0.74 days, followed by ketorolac group where it was 6.10 ± 0.80 days and was highest in control group with mean hospital stay of 8.63 ± 0.67 days (F-coefficient 303.85, P < 0.05) (Table 3 and Fig. 4). Post hoc Tukey analysis further confirmed that all pairwise comparisons were significant (P < 0.001), indicating earlier discharge in fentanyl group. Patients in the control group had the highest frequency of nausea (10.0%) and vomiting (16.7%), while fentanyl group showed the lowest incidence (3.3%) of nausea and vomiting (P < 0.001) (Table 4, Figs. 5 and 6). There were no cases of renal impairment or respiratory depression in any group during the studied 48 h postoperative period. The difference in complication rates among the groups was found to be statistically significant (χ2 = 2.228, P = 0.001), indicating better tolerability in Group fentanyl.

With evolution of various analgesic modalities, the management of postoperative pain has also evolved. Nowadays, multimodal analgesia is preferred for better pain control [10]. Utilization of interventions or drugs targeting multiple steps of the pain pathway can be called multimodal therapy. It allows synergistic action and lowers the total required dose of each drug, thus promoting effective analgesia with fewer side effects [8,11]. Even after having multiple options of analgesic techniques and drugs of multiple classes and potency, postoperative pain is still a troublesome complaint from the patients, and we are still in search of a better combination. There are studies on the effect of LIA when using Ketorolac or Fentanyl. However, there is no study which compares the efficacy of ketorolac to fentanyl when used in LIA. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to directly compare the analgesic efficacy of periarticular fentanyl and ketorolac. In our study we observed that Fentanyl Group provided better results when compared with ketorolac and normal saline group in terms of controlling post-operative pain, early ambulation, and shorter duration of hospital stay. Although nausea and vomiting are usually associated with opioids [12]. However, in our study Fentanyl group had the lowest incidences of the same. We further observed that the nausea and vomiting were more frequent in the normal saline group which might have been because of inadequate pain control necessitating administration of IV Tramadol for analgesia and might have further caused nausea and vomiting. In our study, the local administration of Fentanyl in LIA not only gave better pain relief but also lead to reduced need for systemic opioids, resulting in less frequent nausea and vomiting. For the intraoperative phase of pain control, spinal anesthesia was used. By the time, patients recovered from spinal anaesthesia LIA was functional. This ensured that no pain signals reached the central nervous system at any time before the LIA was initiated to smooth postoperative recovery. To be useful in LIA, the drug must be able to act at the site of injection [4]. Ketorolac is one of the directly acting nonselective NSAIDs which has been used in the past with promising results [4]. When injected together with bupivacaine or ropivacaine, ketorolac further increases the analgesic effect by inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis in the vicinity [4,5]. Similarly, fentanyl can also act peripherally by binding to opioid receptors on peripheral nerves. Furthermore, fentanyl has around 100 times more analgesic potency as compared to morphine, making it an excellent choice for LIA [6,8]. Bupivacaine is a long-acting anesthetic and interrupts transmission of pain signal by blocking the nerve ending [4,8]. Even when it is used alone without NSAIDS or opioids, bupivacaine has shown good analgesic effects. Badner et al. used bupivacaine and epinephrine in LIA and reported better postoperative range of motion and reduced need for postoperative narcotics [13] Moreover, the concurrent usage of corticosteroids or ketorolac with Bupivacaine can further increase these effects [14]. One of the major concerns of chondrotoxic effects of bupivacaine gets practically eliminated as all the cartilage is already sacrificed while doing arthroplasty [8]. Although steroids too have been used in LIA cocktail and have been reported as a safe and effective method, the possibility of infection stopped us from using it in our study [7,15,16]. Our study demonstrated that LIA using a combination of Bupivacaine + Fentanyl has better analgesia as compared to Bupivacaine + Ketorolac. Moreover, LIA with either Fentanyl or Ketorolac both had better pain control as compared to placebo (P < 0.05). Although direct comparative studies between periarticular fentanyl and Ketorolac are scarce, our findings were consistent with the previous study that demonstrated the enhanced postoperative analgesia induced by the use of PAI [4,5,6,7,8,14,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Apart from this, the combination of Bupivacaine + Fentanyl was better tolerated and needed lowest cumulative dosage of Diclofenac in the postoperative period. In a review done by Gibbs et al., it was concluded that LIA does not reduce the hospital stay [22]. However, we observed a significant reduction in the duration of hospital stay in the LIA group (fentanyl as well as ketorolac group) as compared to the placebo group. LIA takes very little time and does not prolong the surgical time. Further, it is well-known technique. The ease of application, no requirement for any sophisticated instruments, readily available and cheap medications make it even more appealing to use. The strength of this study is that it was a triple-blinded study. Selection bias was reduced by randomization and performance bias was avoided by blinding the patient. Observer bias was reduced by blinding the investigator, and detection bias was reduced by blinding the data analyst. To reduce the potential confounding effect of surgical technique on postoperative pain, all procedures were performed by a single experienced surgeon. This approach ensured consistency in surgical execution and minimized the influence of technique-related variability on pain outcomes. This study has several limitations that warrant consideration. The relatively small sample size of 90 patients and the single-center design limits the generalizability of the results and introduce center-specific bias, thereby reducing its external validity. As the study period was limited to 48 h postoperatively, it could not provide any insight into long-term pain control, functional recovery, or delayed complications. In addition, the focus of the study was to assess the immediate postoperative pain scores and duration of hospital stay, whereas other important parameters such as functional outcomes and patient satisfaction were not studied. In addition, the study did not had any measure to assess the cost-effectiveness of the procedure.

LIA in THA offers effective postoperative analgesia while promoting early mobilization and rehabilitation. The combination of bupivacaine and fentanyl provides significantly superior pain relief, reduced postoperative analgesic requirements, fewer complications, and a shorter hospital stay when compared to bupivacaine with ketorolac or normal saline. These findings support the adoption of fentanyl-based periarticular regimens as a safe and efficient strategy to enhance recovery following THA. However, further large-scale, multicenter studies are warranted to validate these findings and assess long-term outcomes.

LIA is advantageous in controlling postoperative pain and should be used more commonly as a part of multimodal analgesia.

References

- 1.Ban WR, Zhang EA, Lv LF, Dang XQ, Zhang C. Effects of periarticular injection on analgesic effects and NSAID use in total knee arthroplasty and total hip arthroplasty. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2017;72:729-36. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Desai AS, Dramis A, Board TN. Leg length discrepancy after total hip arthroplasty: A review of literature. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2013;6:336-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Pirie K, Traer E, Finniss D, Myles PS, Riedel B. Current approaches to acute postoperative pain management after major abdominal surgery: A narrative review and future directions. Br J Anaesth 2022;129:378-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Kerr DR, Kohan L. Local infiltration analgesia: A technique for the control of acute postoperative pain following knee and hip surgery: A case study of 325 patients. Acta Orthop 2008;79:174-83. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Andersen LØ, Kehlet H. Analgesic efficacy of local infiltration analgesia in hip and knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. Br J Anaesth 2014;113:360-74. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Mullaji A, Kanna R, Shetty GM, Chavda V, Singh DP. Efficacy of periarticular injection of bupivacaine, fentanyl, and methylprednisolone in total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2010;25:851-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Sreedharan Nair V, Ganeshan Radhamony N, Rajendra R, Mishra R. Effectiveness of intraoperative periarticular cocktail injection for pain control and knee motion recovery after total knee replacement. Arthroplasty Today 2019;5:320-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Kulkarni R, Pawar H, Panchal S, Prabhu R, Keny SA, Kamble PR, et al. Efficacy of periarticular local infiltrative analgesic injection on postoperative pain control and functional outcome in sequential bilateral total knee replacement: A prospective controlled trial in 120 consecutive patients. Indian J Orthop 2023;57:689-95. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Lunn TH, Husted H, Solgaard S, Kristensen BB, Otte KS, Kjersgaard AG, et al. Intraoperative local infiltration analgesia for early analgesia after total hip arthroplasty: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2011;36:424-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.O’Neill A, Lirk P. Multimodal analgesia. Anesthesiol Clin 2022;40:455-68. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Nakai T, Tamaki M, Nakamura T, Nakai T, Onishi A, Hashimoto K. Controlling pain after total knee arthroplasty using a multimodal protocol with local periarticular injections. J Orthop 2013;10:92-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Benyamin R, Trescot AM, Datta S, Buenaventura R, Adlaka R, Sehgal N, et al. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008;11:S105-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Badner NH, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, MacDonald SJ, Doyle JA. Intra-articular injection of bupivacaine in knee-replacement operations. Results of use for analgesia and for preemptive blockade. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78:734-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Fillingham YA, Hannon CP, Roberts KC, Mullen K, Casambre F, Riley C, et al. The efficacy and safety of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in total joint arthroplasty: Systematic review and direct meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2020;35:2739-58. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Wang JJ, Ho ST, Lee SC, Tang JJ, Liaw WJ. Intraarticular triamcinolone acetonide for pain control after arthroscopic knee surgery. Anesth Analg 1998;87:1113-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Christensen CP, Jacobs CA, Jennings HR. Effect of periarticular corticosteroid injections during total knee arthroplasty. A double-blind randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:2550-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Schubert AK, Wiesmann T, Wulf H, Obert JDA, Eberhart L, Volk T, et al. The analgetic effect of adjuvants in local infiltration analgesia - a systematic review with network meta-analysis of randomized trials. J Clin Anesth 2024;97:111531. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Verdaguer-Figuerola A, Andriola V, Soler-Cano A, Alavedra-Massana A, Carballo A, Tey-Pons M. Local infiltration anesthesia in total hip arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial. Arthroplasty Today 2025;33:101692. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Spreng UJ, Dahl V, Hjall A, Fagerland MW, Ræder J. High-volume local infiltration analgesia combined with intravenous or local ketorolac+morphine compared with epidural analgesia after total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth 2010;105:675-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Zhang Z, Shen B. Effectiveness and weakness of local infiltration analgesia in total knee arthroplasty: A systematic review. J Int Med Res 2018;46:4874-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Pandazi A, Kanellopoulos I, Kalimeris K, Batistaki C, Nikolakopoulos N, Matsota P, et al. Periarticular infiltration for pain relief after total hip arthroplasty: A comparison with epidural and PCA analgesia. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013;133:1607-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Gibbs DM, Green TP, Esler CN. The local infiltration of analgesia following total knee replacement: A review of current literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94:1154-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]