This article covers giant cell tumors around the knee, emphasizing radiological grading and Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) based outcomes

Dr. Prabodh Kantiwal, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Marudhar Industrial Area, 2nd Phase, M.I.A. 1st Phase, Basni, Jodhpur - 342005, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: prabodhkantiwal@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumour (GCT) of bone is a rare, benign yet locally aggressive neoplasm that frequently involves the epiphyseal–metaphyseal regions of long bones, especially around the knee.

Materials and Methods: This retrospective study evaluated 31 patients who underwent surgical treatment for GCT around the knee at a tertiary care center, with a minimum follow-up of 1 year. Patients were staged radiologically using Campanacci grading, with 11 Grade II and 20 Grade III tumors included. Treatment approaches involved extended curettage with sandwich procedures (polymethyl methacrylate cement), bone grafting (autologous or morselized allograft), and wide excision with endoprosthesis. Clinical outcomes were assessed using the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score. The mean MSTS scores were 28.91 for the sandwich procedure, 29.28 for bone grafting, 26.33 for curettage with allograft, and 27.83 for endoprosthesis. Complications were minimal, with one local recurrence and no infections reported. Revision surgeries were required in two patients for non-recurrence-related complications. Postoperative rehabilitation emphasized early mobilization, with tailored weight-bearing protocols based on the reconstruction technique.

Conclusion: This study highlights favorable outcomes across different surgical methods, emphasizing the utility of bone cement as an effective adjuvant in reducing recurrence rates. Limitations include the small sample size, retrospective nature, and lack of direct comparison across all methods.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, musculoskeletal tumor society score, sandwich technique, endoprosthesis, campanacci.

Giant cell tumour (GCT) of bone is a rare, locally aggressive benign tumor primarily affecting the epiphyseal-metaphyseal regions of long bones in young adults aged 20–40 [1,2]. It commonly occurs near the knee, involving the distal femur or proximal tibia, but can also affect other bones like the distal radius or proximal humerus. Clinical symptoms include localized pain, swelling, and reduced joint range of motion (ROM). Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveal characteristic osteolytic lesions, and histology shows mononuclear cells influencing its behavior [3-5]. Extended curettage is the primary treatment for GCT of bone, especially for lesions confined to the bone with minimal soft-tissue involvement [6]. It involves meticulous tumor removal, often enhanced with local adjuvants to lower recurrence risks. However, in Campanacci Grade 3 GCTs, where there is extensive bone destruction and significant soft tissue involvement, curettage may not be feasible. In such cases, wide excision is a better option, ensuring complete tumor removal with a margin of healthy tissue. Though this approach may require reconstruction with prosthetics or bone grafts, it significantly reduces recurrence risk and improves long-term outcomes.

In this study, we aimed to evaluate the clinic-radiological outcomes of surgically treated GCTs around the knee and to compare the effectiveness of various management methods for these tumors.

A retrospective study was conducted in the Department of Orthopaedics at a tertiary care center, involving 31 patients who underwent surgical treatment for GCTs around the knee, with a minimum follow-up of 1 year. The study included adults aged 18 years and older with histopathologically confirmed GCTs located in the proximal tibia, proximal fibula, or distal femur. Only patients who underwent surgical intervention were included, while those deemed unfit for surgery or who declined the procedure were excluded. This study aimed to evaluate outcomes in surgically treated GCT cases in these specific anatomical .

Surgical technique

Curettage

All surgeries were performed under spinal anesthesia with a pneumatic tourniquet applied to the thigh. For distal femoral tumors, a lateral or medial approach was chosen based on the involved condyle. For proximal tibial tumors, either an anterolateral or anteromedial approach was used, depending on the affected condyle. Intralesional curettage was performed through a large cortical window. The procedure was enhanced with the use of electrocautery, a high-speed burr, and liquid phenol. The cavity was meticulously inspected, including hard-to-visualize areas, using a dental mirror to ensure complete removal of tumor remnants.

Reconstruction

Reconstruction of the defect is a critical step in managing GCT. Most patients in our study presented with minimal or absent subchondral bone, necessitating reconstruction to provide structural support for the overlying cartilage and improve nutrition. All patients received iliac crest bone grafts, precisely sized and placed subchondrally. For cavity filling, three options were used: Polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) cement, autologous bone graft, or morselized allograft. The choice of filler was determined based on individual patient factors. After cavity filling, fixation was achieved using a plate and screw construct.

Rehabilitation

Postoperative rehabilitation began with range-of-motion exercises and isometric muscle strengthening starting the day after surgery. For patients with PMMA constructs, weight bearing was initiated at 6 weeks. For those with autografts or allografts, weight bearing was determined based on radiographic evidence of bone healing, assessed at 6-week intervals. For patients with endoprosthesis, assisted weight bearing was initiated the next day after surgery.

Outcome

The primary outcome of interest was clinical improvement, measured using the musculoskeletal tumor society (MSTS) rating score for lower extremities. This score evaluates pain, function, emotional well-being, support, walking ability, and gait. Secondary outcomes assessed included local recurrence, metastasis, the need for revision surgery, infection, osteoarthritic changes, and revisions unrelated to .

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using analysis of variance software (version 29.0.1.1). Patient age was analyzed as a continuous variable and expressed as a mean with standard deviation. Functional outcomes were evaluated using the MSTS score for the lower extremity. The MSTS score was calculated for each patient and then averaged within each surgical treatment group (PMMA, autologous bone graft, morselized allograft, and endoprosthesis) for comparison. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient demographics, tumor characteristics, and treatment modalities. Continuous variables, such as age and MSTS score, were reported as mean ± standard deviation.

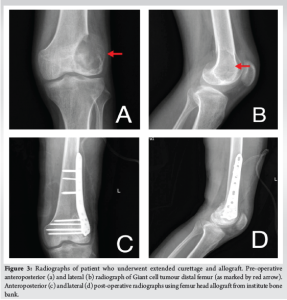

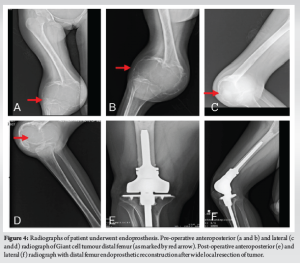

The average age of the patients in the study was 35.69 ± 12.75 years (range: 18–69 years). There were 18 men and 13 women. The distal femur were 12 and proximal tibia were 19 involved in our study. 29 patients had a primary GCT while 2 patients had a recurrent GCT. The tumors were staged radiologically using the Campanacci grading. There were eleven cases of Grade II tumor and twenty cases of Grade III tumor. Five patients had pathological fracture at presentation. In our study, 6 underwent the sandwich procedure using PMMA as a void filler (Fig. 1), 10 underwent extended curettage and autologous bone graft (Fig. 2), 11 underwent extended curettage and morselized allograft (Fig. 3), and 4 patients underwent endoprosthesis (Fig. 4).

Knee ROM and MSTS score

27 patients regained a knee flexion of more than 90° while 4 patients had a knee flexion up to 70° were of femoral GCT with campanacci grade 3. Extension was attained fully in all the cases. The musculoskeletal tumor rating score for the lower extremity was applied for functional status of the patient. The mean MSTS rating score of our study was 28.91 for sandwich procedure with PMMA, 29.28 for extended curettage and autologous bone graft, 26.33 for extended curettage and morselized allograft, and 27.83 for .

Complications

All patients were available for the final follow-up. One local recurrence was seen in the patient with distal thigh GCT after 1 year of the surgery. Osteoarthritis developed in 1 patient who had distal femur GCT and underwent sandwich procedure with PMMA cement. No infection was observed in any of the patients. No metastasis was noticed. Two patients underwent revision surgery for non-recurrence of tumor-related issues as of wound.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the clinical and radiological outcomes in patients with GCTs around the knee who underwent surgical treatment, with a minimum follow-up period of 1 year. GCT is a benign primary bone tumor that is locally aggressive but has the potential for malignant metastasis [3-7]. It accounts for 5–7% of all primary bone tumors and approximately 20% of benign bone tumors [8]. Typically, GCTs occur in the epiphyseal-metaphyseal regions of long bones and predominantly affect individuals aged 20–40 years. Our study included 31 patients with GCTs around the knee. Of these, 19 patients (61%) had tumors in the proximal tibia, while 12 patients (39%) had tumors in the distal femur. A significant proportion, 20 patients (64.5%), fell within the 20–40 age group. As per to literature, it has shown more female preponderance than male [9]. Our study had involved 18 males (58%) making it greater than females in the study period, but it was statistically not significant. GCT can present with a vast variety of symptoms, for example, pain, swelling, decreased joint mobility, fracture of involved bone, neurovascular involvement of the limb, or accidental finding while routine check-up. Most of the patients enrolled in our study presented with above above-listed complaints but 5 (16.12%) of 31 patients presented with pathological fracture around knee. Evaluation for GCT involves non-invasive and invasive modalities. Initial radiographs and MRI are usually performed where it appears as a pure lytic cystic lesion that frequently, though not always, grows eccentrically in the epiphysio-metaphyseal area of the bone. The bone’s afflicted region may enlarge, while the cortical bone may become thinner. In an advanced stage, the GCT breaks through the cortex, and the production of spicules around the tumour occurs in the absence of periosteal response [5]. The MRI indicators of GCT include evidence of tissue haemorrhages, high contrast medium enhancement, and high signal intensity in T2-weighted images [10]. As per the description given for GCT [11], 11 (35.48%) patients belonged to grade II, and 20 (64.52%) patients were of grade III in our conducted study. Systematic analysis of existing literature suggests that Campanacci Grade III GCTs are commonly associated with pathological fractures at presentation [12]. Of the 5 pathological fractures in our study, all belonged to Campanacci grade III. Extended curettage has been used to treat GCT for a long time [6]. The tumor can be removed either by broad excision or curettage with or without local adjuvants depending on the involvement of the articular surfaces. In one of our previous published study of synchronous GCT around talus, we have performed extended curettage and allograft to treat the bone defect and provide mechanical stability and there was no local recurrence of tumor or altered joint functionality [13]. However, the question of restoring bone abnormalities has been divisive ever since. Several studies have shown that bone cement or bone transplants can be used to treat a bone deficit. There are currently no high-quality comparison studies in the literature that expressly assess the GCT around the knee joint and include a specific Campanacci grading. In our study, 7 patients underwent extended curettage and bone grafting, 6 patients underwent wide excision and endoprosthesis. Of the 25 patients for bone defect after curettage, 12 patients underwent sandwich procedure, 7 underwent wide excision and autograft from iliac crest or iliac crest and fibular strut and 6 underwent bone cement. Bone cement as an adjuvant with bone graft was used in all the extended curettage patients for deficit bone. The use of bone cement as an adjuvant reduced the local recurrence rate in individuals who had curettage to 12–27% [14]. The result of a methodical effort to reduce recurrence rates is the use of a wide variety of adjuvants after curettage, such as the local application of phenol, PMMA, liquid nitrogen, or a combination of many choices. Probably, the most well-established treatment to employ after curettage is phenol and PMMA. In our study, we included only primary or recurrent GCTs belonging to grade II or III and reported local recurrence only in 1 patient who underwent sandwich procedure after 1 year of follow-up. Post-operative infection is one of the common complications noted in most of the surgeries. Here, in case of GCTs around knee, infection rate is compared between intralesional curettage and wide excision studies conducted in past [6]. They reported an infection rate of 5.8%. A systematic analysis that included one of the largest series of wide resections for GCTs reported an infection rate of 6.3% [12]. We reported no infection around knee in our study. The need for revision surgery is needed in case of local recurrence, infection, or implant-related complications. A systematic analysis [12] reported that revision surgeries were frequently required following endoprosthesis, with rates exceeding 40% in some series. In our retrospective study, there was no revision surgery needed. The MSTS rating scores reported in the various series frequently represented exceptional or excellent functional results [12]. In our study, MSTS mean was 28.91 for sandwich procedure, 29.28 for extended curettage and bone graft, 26.33 for extended curettage and bone cement, and 27.83 for endoprosthesis.

This study highlights the effectiveness of surgical approaches in managing GCTs around the knee, including extended curettage with adjuvants, bone grafting, and wide excision with endoprosthesis. Functional outcomes, as assessed by the MSTS score, were favorable across techniques, with low recurrence rates and minimal complications, including no infections. Bone cement as an adjuvant proved beneficial in reducing recurrence. Tailoring the surgical approach to tumor grade, local spread, and patient-specific factors is crucial. Despite the study’s limitations, such as a small sample size and retrospective design, it provides valuable insights into optimizing treatment for GCTs in a critical region.

This study focuses on the clinico-radiological outcomes of GCTs around the knee and evaluates the functional outcomes of various surgical approaches using MSTS scores. To our knowledge, it is one of the few studies that compare functional outcomes across different surgical methods for various tumor grades using MSTS scores.

References

- 1.Ebeid WA, Badr IT, Mesregah MK, Hasan BZ. Risk factors and oncological outcomes of pulmonary metastasis in patients with giant cell tumor of bone. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2021;20:101499. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Machak GN, Snetkov AI. The impact of curettage technique on local control in giant cell tumour of bone. Int Orthop 2021;45:779-89. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Pitsilos C, Givissis P, Papadopoulos P, Chalidis B. Treatment of recurrent giant cell tumor of bones: A systematic review. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:3287. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Jo VY, Demicco EG. Update from the 5th edition of the World Health Organization classification of head and neck tumors: Soft tissue tumors. Head and Neck Pathol 2022;16:87-100. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Hakim DN, Pelly T, Kulendran M, Caris JA. Benign tumours of the bone: A review. J Bone Oncol 2015;4:37-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Jamshidi K, Bagherifard A, Mohaghegh MR, Mirzaei A. Fibular strut allograft or bone cement for reconstruction after curettage of a giant cell tumour of the proximal femur: A retrospective cohort study. Bone Joint J 2022;104:297-301. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Palmerini E, Picci P, Reichardt P, Downey G. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone: A review of the literature. Technol Cancer Rese Treat 2019;18:1533033819840000. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Choi JH, Ro JY. The 2020 WHO classification of tumors of bone: An updated review. Adv Anatomic Pathol 2021;28:119-38. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Jamshidi K, Karimi A, Mirzaei A. Epidemiologic characteristics, clinical behavior, and outcome of the giant cell tumor of the bone: A retrospective single-center study. Arch Bone Joint Surg 2019;7:538. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Parmeggiani A, Miceli M, Errani C, Facchini G. State of the art and new concepts in giant cell tumor of bone: Imaging features and tumor characteristics. Cancers (Basel) 2021;13:6298. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Obiegbu HO. Turn down distal femoral autograft in proximal tibia defect reconstruction-a case report. Afrimed J 2021;7:50-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Do Brito JS, Spranger A, Almeida P, Portela J, Barrientos-Ruiz I. Giant cell tumour of bone around the knee: A systematic review of the functional and oncological outcomes. EFORT Open Rev 2021;6:641-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Yadav SK, Kantiwal P, Rajnish RK, Garg A, Aggarwal D. Synchronous multicentric giant cell tumour of immature skeleton with epiphysiometaphyseal origin. BMJ Case Rep CP 2023;16:e254216. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Li H, Gao J, Gao Y, Lin N, Zheng M, Ye Z. Denosumab in giant cell tumor of bone: Current status and pitfalls. Front Oncol 2020;10:580605. [Google Scholar | PubMed]