This case demonstrates the practicality and methodical implementation of total en bloc spondylectomy for addressing thoracic spinal metastasis due to renal cell carcinoma with stresses on the validated scoring systems such as the modified Tokuhashi and Spine Instability Neoplastic Scores assisting in surgical decision-making.

Dr. Jeevan Kumar Sharma, Indian Spinal Injuries Centre, Vasantkunj, New Delhi - 110070, India. E-mail: jeev208@gmail.com

Introduction: Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is notorious malignancy that could metastasize to lungs, lymph nodes, bones, and other internal organs. The spine is the most common area among bones where it metastasizes. Two main concerns for the spine surgeon regarding spinal metastasis are the stability of the spine and the prognosis of the disease. Total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) is a well-known procedure employed for the excision of metastatic lesion to the spine.

Case Report: We report a case of 61-year-old elderly male with RCC with a past history of pulmonary metastasis, who presented to our institute with complaints of back pain and limited mobility in 2024. Radiological evaluation detected the lesion of the T8 vertebra. The patient underwent comprehensive evaluation with validated scoring systems (Modified Tokuhashi score of 10, and Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score of 14). Pre-operative embolization and then TES of the T8 vertebra was performed. There were no perioperative complications and he was able to mobilize post-operatively with some improvement in his neurological status.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates the step-by-step approach of TES for the malignant spread of RCC to T8 vertebra with rewarding perioperative results.

Keywords: Metastasis, spine, renal cell carcinoma, spondylectomy, total en bloc spondylectomy.

Nearly 50 percent of older cancer patients with bone metastases had the spine affected. Bone metastases are frequently encountered in these individuals with other malignancy [1]. Lung metastases are the most frequent in renal cell carcinoma (RCC), with 20–35% of cases involving bone involvement, followed by lymph nodes, liver, adrenal glands, and brain [2]. The quality of life for cancer patients has increased due to advancements in radiation therapy, surgery, and medicine. Patients with bone metastases now have better survival rates and functional status [3]. Contrary to the belief of hematogenous dissemination, a recent study has supported a locoregional spread mechanism of early spinal dissemination of RCC [4]. As a spine surgeon, we are more concerned of two main entities for spinal metastasis: stability of the spine and prognosis of the patient. Various scoring systems have been described for pre-operative assessment of the patient with metastasis to the spine. Two widely used scoring systems for identifying the best course of treatment are the New England Spinal Metastasis Score and the Revised Tokuhashi score (RTS) [5]. The primary tumor site classification and the effects of hormone therapy and chemotherapy are included in the new Katagiri score for the prognosis of skeletal metastasis [6]. A more thorough operation plan can be created by using the Kostuik classification and the spine instability neoplastic score (SINS), which are frequently used to assess spine stability [7]. Total en bloc spondylectomy (TES) and separation surgery with post-operative stereotactic radiosurgery (SSRS) are the two major types of surgical techniques for isolated metastatic patients [8]. Here, we report a case of clear cell type RCC with thoracic spine (T8) metastasis managed with a TES at the Hospital for Advanced Medicine and Surgery, Kathmandu, Nepal.

Patient information

A 61-year-old male patient, previously diagnosed with RCC in 2019, presented with a history of back pain and difficulty walking in 2024. He underwent nephrectomy 5 years ago, and his RCC had metastasized to the lungs in 2020. He was treated with Sunitinib, and a Positron Emission Tomography scan in 2022 showed no evidence of active disease. In May 2024, the patient developed back pain, and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) revealed metastasis to the T8 vertebra with minimal cord compression. He had paraparesis at that time and received 10 cycles of radiotherapy, which resulted in some neurological improvement. However, in November 2024, the patient continued to report back pain and had difficulty walking.

Clinical examination

Upon examination, the patient had the following neurological findings:

- Motor: Bilateral lower extremity strength was 4/5 (American Spinal Injury Association scale)

- Sensory: Sensory function was partially preserved (50%) in the bilateral lower limb

- Bowel/Bladder: Normal function.

Imaging

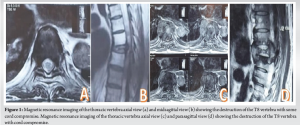

- MRI (May 2024): demonstrated metastasis at the T8 with cord compression (Fig. 1a and b), while MRI (November 2024): revealed continued deterioration at the T8 level (Fig. 1c and d).

Pre-operative planning

- Given the prognosis of more than 6 months survival (RTS = 10 points) and features of instability (SINS score = 14), the patient was deemed a candidate for TES. The surgery planned involved the TES of T8 vertebrae, including excision of Costo-vertebral joints of T8 and T9 to gain access and to relieve spinal cord compression.

- A detailed computed tomography angiography was performed to assess the vascular supply to the affected vertebrae.

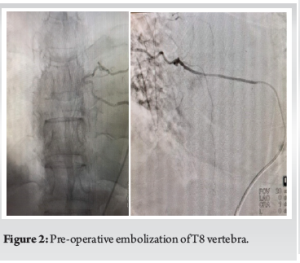

- Embolization: Pre-operative embolization of the T8 vertebra was performed to minimize bleeding and enhance the resection process (Fig. 2).

Surgical procedure

Posterior decompression of T8 Vertebra

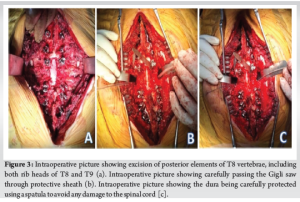

The surgery began with a posterior approach for the exposure of the thoracic spine. The excision of posterior elements of T8 vertebrae, including both rib heads of T8 and T9, was performed (Fig. 3a).

Anterior decompression

A Gigli saw was passed through the neural disc space to facilitate the excision of the affected vertebrae (Fig. 3b).

Spinal cord protection

During excision, the dura was carefully protected using a spatula to avoid any damage to the spinal cord (Fig. 3c).

Stabilization

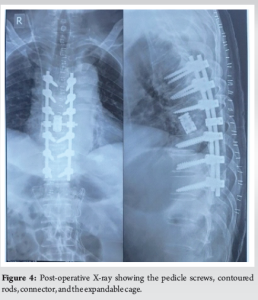

Pedicle screws were placed at the T5, T6, T7, T9, T10, and T11 levels. An expandable cage was inserted at the T8 level along with contoured rods and an interrod connector to provide spinal stability (Fig. 4).

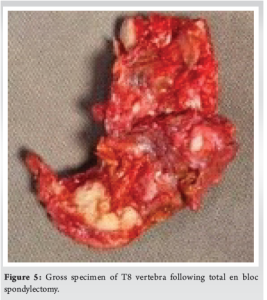

The gross specimen was sent to pathology for histopathological examination and it turned out to be the metastatic lesion from clear cell type RCC (Fig. 5).

Post-operative course

The patient was closely monitored in the intensive care unit following the surgery. His intraoperative blood loss was 645 mL. There was no neurological deterioration, and he began rehabilitation therapy after a few days. Pain management was optimized, and his walking ability improved over the subsequent days.

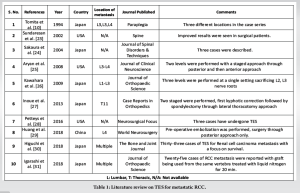

Spinal metastases from RCC, especially in the thoracic spine, pose a significant challenge to both diagnosis and treatment. Although RCC metastasize mainly to the vertebra, isolated intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from RCC has also been reported [9]. The presence of epidural cord compression can lead to permanent neurological deficits if not treated promptly. TES, while technically demanding, offers the advantage of complete tumor excision and, in select cases, improves both pain control and neurological outcomes. TES, initially defined by Tomita et al., is a surgical procedure used in oncological spine surgery to remove the complete vertebral body and posterior parts as single pieces to achieve negative margins [10,11]. Other than isolated metastasis to the spine, TES has been utilized for aggressive hemangiomas of vertebrae [12], oligometastatic liposarcoma [13], spinal giant cell tumors combined with secondary aneurysmal bone cyst [14], chondrosarcoma, chordoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, osteosarcoma, and osteoblastoma [15]. Paholpak et al. demonstrated posterior-only TES for L3-involved vertebrae, which yielded excellent results in the local control of metastatic disease [16]. There has been a great evolution in the literature regarding the management of metastatic lesions to the spine. TES has been performed in metastatic RCC to the spine. The previous reports have been illustrated in Table 1. TES is a commonly used technique; however, it is not devoid of its drawbacks, particularly when combined with primary malignant and metastatic disorders [17]. Implant failure was found to be prevalent in patient undergoing surgery for metastasis to the spine [18]. TES is also linked to substantial blood loss since it requires extensive tissue dissection, bone work, and a lengthy operative period [19]. Demura et al. reported the following potential TES complications: bleeding over 2,000 mL, hardware failure, neurological complications, surgical site infection, wound dehiscence, cerebrospinal fluid leakage, and respiratory and cardiovascular complications [20]. Tsukamoto et al. reported that, to select the optimal treatment for spinal metastasis, neurological status by epidural spinal cord compression grade (axial T2-weighted magnetic resonance image), mechanical instability by SINS scoring system, and systemic disease should be evaluated by a multidisciplinary team [21]. Cao et al. compared two major surgical procedures TES and SSRS. They were reported as efficient methods for treating solitary spinal metastasis patients with metastatic spinal cord compression. Better local tumor control and mental health were found in the TES group, and most patients felt as if they were free of spinal tumors. Compared with TES, the SSRS caused less operation-related trauma [8]. According to Terzi et al., the primary prognostic markers influencing overall survival for spinal metastases in clear cell type RCC were high Tokuhashi score, the existence of visceral metastases, additional bone metastases, and the kind of surgery [22]. In this case, we describe the step-by-step approach of management, each surgical step of the TES procedure for metastatic lesion of clear cell RCC to T8 vertebra with no perioperative complications being encountered. The patient was able to mobilize post-surgery though it might be palliative care for him. The decision to proceed with surgery should be made carefully, considering the patient’s overall prognosis, the extent of metastasis, and the potential for neurological recovery and symptoms of instability, such as severe pain. The use of pre-operative embolization to control bleeding and the step-by-step procedure of the surgery could lead to good outcomes.

This case highlights the feasibility and step-by-step approach of TES in the treatment of thoracic spinal metastasis from RCC along with the review of the literature. Early diagnosis and intervention are critical to improving the quality of life and preventing irreversible neurological damage. Validated scoring systems, such as modified Tokuhashi score and SINS score could help surgeons in decision-making of surgery.

In patients with mechanical instability and favorable prognostic scores, TES is a viable and effective surgical approach for addressing solitary thoracic spinal metastasis from RCC. It is crucial for determining surgery with the help of validated scoring systems, such as the Modified Tokuhashi Score and SINS. This case illustrates the significance of employing a multidisciplinary approach, the value of pre-operative embolization to reduce intraoperative bleeding, and careful surgical technique to enhance neurological and functional outcomes – even in palliative situations.

References

- 1.Aebi M. Spinal metastasis in the elderly. Eur Spine J 2003;12 Suppl 2:S202-13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Umer M, Mohib Y, Atif M, Nazim M. Skeletal metastasis in renal cell carcinoma: A review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2018;27:9-16. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Kurisunkal V, Gulia A, Gupta S. Principles of management of spine metastasis. Indian J Orthop 2020;54:181-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Attalla K, Duzgol C, McLaughlin L, Flynn J, Ostrovnaya I, Russo P, et al. The spinal distribution of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: Support for locoregional rather than arterial hematogenous mode of early bony dissemination. Urol Oncol 2021;39:196.e9-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Mavritsakis D, Amiot LP. A novel prognostic scoring system combining the revised Tokuhashi score and the New England spinal metastasis score for preoperative evaluation of spinal metastases. Front Surg 2024;11:1349586. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Kobayashi K, Ando K, Nakashima H, Sato K, Kanemura T, Yoshihara H, et al. Prognostic factors in the new Katagiri scoring system after palliative surgery for spinal metastasis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2020;45:E813-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Xu C, Yin M, Sun Z, Yan Y, Mo W, Yan W. An independent interobserver reliability and intraobserver reproducibility evaluation of spinal instability neoplastic score and kostuik classification systems for spinal tumor. World Neurosurg 2020;137:e564-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Cao S, Gao X, Zhang Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Wang T, et al. A comparison of two different surgical procedures in the treatment of isolated spinal metastasis patients with metastatic spinal cord compression: A case-control study. Eur Spine J 2022;31:1583-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Kalimuthu LM, Ora M, Gambhir S. Recurrent renal carcinoma with solitary intramedullary spinal cord metastasis. Indian J Nucl Med 2020;35:358-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Tomita K, Toribatake Y, Kawahara N, Ohnari H, Kose H. Total en bloc spondylectomy and circumspinal decompression for solitary spinal metastasis. Paraplegia 1994;32:36-46. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Tomita K, Kawahara N, Baba H, Tsuchiya H, Fujita T, Toribatake Y. Total en bloc spondylectomy: A new surgical technique for primary malignant vertebral tumors. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1997;22:324-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Brunette-Clément T, Weil AG, Shedid D. Total en bloc spondylectomy of locally aggressive vertebral hemangioma in a pediatric patient. Childs Nerv Syst 2021;37:2115-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Saha P, Raza M, Fragkakis A, Ajayi B, Bishop T, Bernard J, et al. Case report: L5 tomita en bloc spondylectomy for oligometastatic liposarcoma with post adjuvant stereotactic ablative radiotherapy. Front Surg 2023;10:1110580. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Hua W, Guo T, Li X, Wu Q, Yang C. Total en bloc spondylectomy of thoracic giant cell tumor with secondary aneurysmal bone cyst: Case reports and review of literature. Int J Neurosci 2023;133:1309-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Smith I, Bleibleh S, Hartley LJ, Rehousek P, Hughes S, Grainger M, et al. Blood loss in total en bloc spondylectomy for primary spinal bone tumours: A comparison of estimated blood loss versus actual blood loss in a single centre over 10 years. J Spine Surg 2022;8:353-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Paholpak P, Morimoto T, Wisanuyotin T, Sirichativapee W, Sirichativapee W, Kosuwon W, et al. Clinical and oncologic outcomes of posterior only total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal metastasis involving third lumbar vertebra: A case series. Medicine (Baltimore) 2024;103:E37145. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Jones M, Alshameeri Z, Uhiara O, Rehousek P, Grainger M, Hughes S, et al. En bloc resection of tumors of the lumbar spine: A systematic review of outcomes and complications. Int J Spine Surg 2021;15:1223-33. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Wong YC, Chau WW, Kwok KO, Law SW. Incidence and risk factors for implant failure in spinal metastasis surgery. Asian Spine J 2020;14:878-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Sciubba DM, De la Garza Ramos R, Goodwin CR, Xu R, Bydon A, Witham TF, et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy for locally aggressive and primary malignant tumors of the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J 2016;25:4080-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Demura S, Kato S, Shinmura K, Yokogawa N, Shimizu T, Handa M, et al. Perioperative complications of total en bloc spondylectomy for spinal tumours. Bone Joint J 2021;103-B:976-83. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Tsukamoto S, Mavrogenis AF, van Langevelde K, van Vucht N, Kido A, Errani C. Imaging of spinal bone tumors: Principles and practice. Curr Med Imaging 2022;18:142-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Terzi S, Pipola V, Griffoni C, Trentin F, Carretta E, Monetta A, et al. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma spinal metastases: Which factors matter to the overall survival? A 10-year experience of a high-volume tumor spine center. Diagnostics (Basel) 2022;12:2442. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Sundaresan N, Rothman A, Manhart K, Kelliher K. Surgery for solitary metastases of the spine: Rationale and results of treatment. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2002;27:1802-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Sakaura H, Hosono N, Mukai Y, Ishii T, Yonenobu K, Yoshikawa H. Outcome of total en bloc spondylectomy for solitary metastasis of the thoracolumbar spine. J Spinal Disord Tech 2004;17:297-300. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Aryan HE, Acosta FL, Ames CP. Two-level total en bloc lumbar spondylectomy with dural resection for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Neurosci 2008;15:70-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Kawahara N, Tomita K, Murakami H, Demura S, Satomi K, Atomi Y. Total en bloc spondylectomy and a greater omentum pedicle flap for a large bone and soft tissue defect: Solitary lumbar metastasis from renal cell carcinoma. J Orthop Sci 2009;14:830-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 27.Inoue Y, Takahashi H, Yokoyama Y, Iida Y, Fukutake K, Takamatsu R, et al. Treatment of renal cell carcinoma with 2-stage total en bloc spondylectomy after marked response to molecular target drugs. Case Rep Orthop 2013;2013:916501. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 28.Petteys RJ, Spitz SM, Goodwin CR, Abu-Bonsrah N, Bydon A, Witham TF, et al. Factors associated with improved survival following surgery for renal cell carcinoma spinal metastases. Neurosurg Focus 2016;41:E13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 29.29. Huang W, Wei H, Cai W, Xu W, Yang X, Liu T, et al. Total en bloc spondylectomy for solitary metastatic tumors of the fourth lumbar spine in a posterior-only approach. World Neurosurg 2018;120:e8-16. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 30.Higuchi T, Yamamoto N, Hayashi K, Takeuchi A, Abe K, Taniguchi Y, et al. Long-term patient survival after the surgical treatment of bone and soft-tissue metastases from renal cell carcinoma. Bone Joint J 2018;100B:1241-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 31.Igarashi T, Murakami H, Demura S, Kato S, Yoshioka K, Yokogawa N, et al. Risk factors for local recurrence after total en bloc spondylectomy for metastatic spinal tumors: A retrospective study. J Orthop Sci 2018;23:459-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]