Helps in keeping rare case diagnoses in mind.

Dr. Sri Ravindranath Vutukuru, Department of Orthopaedics, ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Sanathnagar, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: vsravindranath@rediffmail.com

Introduction: The clavicle is an uncommon site for tumors, as it is a flat bone and rarely affected by neoplasms. Most clavicular tumors are malignant, with metastases and Ewing’s sarcoma being the most common. Overall, clavicular neoplasms account for <1% of all bone tumors, and chondromyxoid fibroma (CMF) is particularly rare, comprising <1% of cases. This tumor typically arises in the metaphysis of the proximal tibia.

Case Report: A young male patient comes with lateral end clavicle swelling, which on radiologically was diagnosed giant cell tumor. Later on, needle biopsy was thought to be an aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC). Finally, it turned out to be CMF on biopsy.

Conclusion: This case report presents a rare instance in which CMF was initially misdiagnosed as a giant cell tumor based on radiological findings and later as an ABC after histopathological examination. The definitive diagnosis of CMF was only confirmed following excisional biopsy.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, aneurysmal bone cyst, denosumab, excisional biopsy, chondromyxoid fibroma.

The clavicle is the only flat bone in the human body and lacks a definitive medullary canal. It is the first bone to ossify during embryonic development, undergoing intramembranous ossification with two primary ossification centers and one secondary ossification center. Being a subcutaneous bone, it is easily palpable along its entire length. Tumors of the clavicle are rare, accounting for <1% of all bone tumors. Common causes of pain and swelling around the clavicle include osteomyelitis, osteoarthritis, callus formation following a fracture, osteonecrosis, hyperostosis, non-union, chondro-osteopathia costalis (Tietze syndrome), Paget’s disease, Schwannoma, and neoplasms – of which malignant tumors are more common than benign ones. Chondromyxoid fibroma (CMF) is a rare benign cartilaginous tumor that typically occurs between the second and third decades of life, with another peak incidence between the fifth and seventh decades. It affects both genders equally. The most common sites of occurrence are the lower limbs, particularly the metaphysis of the proximal tibia and distal femur, as well as the pelvis, spine, and sternum. Involvement of the upper limbs is extremely rare.

A 26-year-old male patient with a history of slowly growing swelling over the left clavicle for the past 6 months which began with the size of a peanut was insidious in onset and gradually progressive in size. The swelling was associated with a constant dull aching type of pain. There was no history of trauma, constitutional symptoms, pus discharge, or similar complaints or swelling in other limbs or the body.

Local examination (Fig. 1):

- Single, globular swelling

- Confined to lateral 1/3rd of the clavicle measuring 7 cm × 5 cm which was fixed to the underlying bone and slightly tender on palpation

- Bony hard consistency

- The skin over the swelling was normal and pinchable

- The range of movements of the shoulder was near normal with mild painful terminal abduction

- No similar abnormal swellings were noted over the opposite shoulder and other parts of the body

- No local rise of temperature, no neurovascular deficits, and no palpable lymph nodes.

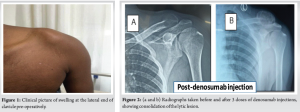

Radiologically, as in (Fig. 2a), it was thought of giant cell tumor (GCT), as it appears to be lytic lesion with internal septae and soap bubble appearance, narrow zone of transition, no periosteal reaction, eccentric lesion in a young male.

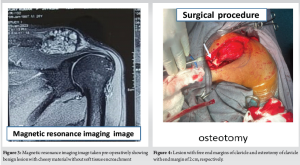

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 3) shows a benign lesion with cheesy material, no periosteal reaction, and without much soft tissue encroachment.

The biomechanical markers were within normal limits, and the skeletal survey showed no other lesions anywhere in the body.

Needle biopsy was done, and we passed a needle into the mass easily through the cortex surrounding the tumor which was thinned and expanded, obtained frank blood with clots, and sent for histopathological examination which came out to be inconclusive.

So we have a trial of denosumab injections to make it consolidate and make it easy for resection. Three doses of 60 mg subcutaneous denosumab were given at an interval of 1 month, and plain radiographs were taken before and after the injection as shown in (Fig. 2a and b).

As the lesion was consolidated with denosumab (Fig. 2b), it was diagnosed as a giant cell tumor.

Then, excisional biopsy was planned after making the patient fit.

Surgical procedure

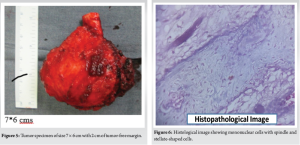

Position – Beach chair position

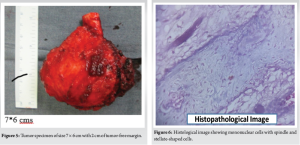

Incision – The lesion was well outlined with a marker, 10 cm. Horizontal incision was given over the lesion extending 2.5 cm medially over the normal clavicle shaft and laterally up to the acromioclavicular joint. Subcutaneous dissection was done. The tumor was exposed and 2 cm of tumor-free region of the clavicle medially was marked, and osteotomy of the clavicle was done (Fig. 4). The tumor was carefully separated from surrounding soft tissues and excision was done. Tumor size was 7 × 6 cm and was sent for histopathological examination (Fig. 5).

The tumor bed was free. No reconstruction was done. A thorough wash was given, and wound was closed. Shoulder range of motion was started on the 1st postoperative day.

But surprisingly, the histopathological report came out to be CMF (Fig. 6).

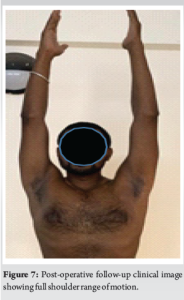

Immediately, on the next post-operative day, we started shoulder range of motion actively, and he attained full range of motion within 2 weeks and joined his regular activities.

Post-operative follow-up does not show any recurrence or remnants (Fig. 7).

The incidence of neoplasms in the clavicle is <1%. Their distribution is as follows: 51% occur in the lateral third (21% benign or intermediate and 30% malignant), 5% in the middle third (3% benign or intermediate, 2% malignant), and 44% in the medial third (28% benign or intermediate, 16% malignant). Among all bone tumors of the clavicle, 20% are benign, 27% are classified as intermediate (locally aggressive and/or rarely metastasizing), and 53% are malignant. The most common clavicular bone tumor is eosinophilic granuloma, followed by bone metastases, plasma cell myeloma, Ewing’s sarcoma, osteosarcoma, aneurysmal bone cyst (ABC), osteochondroma, chondrosarcoma, malignant lymphoma, and fibrous dysplasia. The overall benign/intermediate-to-malignant ratio is approximately 1:1.1 [1]. CMF is an extremely rare benign tumor, accounting for about 1% of all bone tumors. The World Health Organization classifies CMF as a benign tumor characterized by spindle or stellate-shaped cells embedded in abundant myxoid or chondroid intercellular material. It most commonly affects individuals in their second and third decades of life, with typical locations including the metaphysis of long bones (tibia and distal femur), as well as the ilium, scapula, ribs, and sternum. CMF is a slow-growing tumor that presents with mild or dull-aching pain, similar to other benign bone tumors. Malignant transformation is rare (1–2%), and distant metastases have not been reported. To date, only eight cases of clavicular CMF have been documented in PubMed. Soares et al. reported a case of mid-shaft clavicular CMF with a pathological fracture, diagnosed through computed tomography-guided biopsy and successfully treated with en bloc resection, fibula grafting, and fixation using a clavicle locking compression plate [2]. Arora et al. described a case involving the medial two-thirds of the clavicle, confirmed through open biopsy and later resected, with no recurrence observed over 22 months [3]. Pattamapaspong et al. reported a CMF case at the distal clavicle, treated with curettage and bone grafting, with no recurrence after 37 months [4]. Hope et al. also documented a distal clavicular CMF case, diagnosed through open biopsy and treated with curettage, phenol application, and bone grafting, without recurrence [5]. Clinically and radiologically, CMF can mimic GCT or ABC. Even at the microscopic level, CMF presents with hypercellular lobular peripheries and scattered osteoclast-like giant cells. In this case, the tumor was initially misdiagnosed as GCT, and the patient was treated with denosumab, which led to the consolidation of the lesion. Denosumab is a fully human monoclonal immunoglobulin G2 antibody that binds with high affinity and specificity to both soluble and membrane-bound receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B-Ligand (RANKL). By inhibiting RANK activation, it suppresses osteoclast formation, activation, and survival, thereby reducing bone resorption and tumor-induced bone destruction. GCTs of bone and other giant cell-rich tumors (GCRTB) share histological features, including the presence of osteoclastic giant cells and RANK/RANKL expression. GCRTB encompasses a distinct group of rare benign bone and cartilage tumors, including ABC, giant cell granulomas, osteoblastomas, chondroblastomas, and CMFs [6]. Given their similar microscopic features and RANKL expression, these tumors demonstrate a comparable response to denosumab [7]. In this case, denosumab was administered based on the initial GCT diagnosis, and the lesion responded accordingly. However, the final diagnosis after further evaluation confirmed the tumor as CMF.

CMF should be considered as a differential diagnosis next to ABC, GCT, or simple bone cyst and others which are clinically and radiologically similar, except ABC shows fluid levels on MRI, the remaining show few distinct features on MRI. The site of this benign neoplasm is so also very rare and should be investigated and evaluated carefully; however, the treatment is similar to GCT.

CMF is a rare benign bone tumor that should be included in the differential diagnosis of lytic lesions. MRI helps distinguish it from similar entities, and treatment is similar to that of GCT.

References

- 1.Priemel MH, Stiel N, Zustin J, Luebke AM, Schlickewei C, Spiro AS. Bone tumours of the clavicle: Histopathological, anatomical and epidemiological analysis of 113 cases. J Bone Oncol 2019;16:100229. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Soares D, Bernardes F, Silva NV, Silva MC, Lopes D. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the clavicle: A case report of a rare clinical entity. Case Report Ortho Res 2023;6:.45-52 [doi: 10.1159/000536138]. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]

- 3.Arora, Sumit & Kashyap, Abhishek & Maini, Lalit & Prakash, Anjali & Saran, R. Chondromyxoid Fibroma of Clavicle Presenting as Radiological Disappearance of Bone. Annals of the National Academy of Medical Sciences (India). 2003;59. 10.1055/s-0043-1764435. ://doi.org/ 10.1055/s-0043-1764435. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]

- 4.Pattamapaspong N, Peh WC, Tan MH, Hwang JS, Tan PH. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the distal clavicle. Pathology 2006;38:464-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Hope JM, Sane JC, Souleymane D, Mugabo F, Bitega JP, Nikiema AN, et al. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the distal clavicle: Report of an additional case at very unusual anatomic location. JOJ Orthop Orthol Surg 2018;2:555581. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.van der Heijden L, Dijkstra PD, van de Sande MA, Kroep JR, Nout RA, van Rijswijk CS, et al. The clinical approach toward giant cell tumor of bone. Oncologist 2014;19:550-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Lipplaa A, Schreuder WH, Pichardo SE, Gelderblom H. Denosumab in giant cell rich tumors of bone: An open-label multicenter phase II study. Oncologist 2023;28:1005-e1104. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;286:241-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Başbozkurt M, Ateşalp S, Şarlak AY, Tunay S, Yıldırım Y. Chondromyxoid fibroma [in Turkish] Deniz Tıp Bülteni 1993;26:95-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Merine D, Fishman EK, Rosengard A, Tolo V. Chondromyxoid fibroma of the fibula. J Pediatr Orthop 1989;9:468-71. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Desai SS, Jambhekar NA, Samanthray S, Merchant NH, Puri A, Agarwal M. Chondromyxoid fibromas: A study of 10 cases. J Surg Oncol 2005;89:28-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]