A 4–5 ECA-based vascularized bone graft offers a potentially effective solution for revascularization and functional recovery in hamate avascular necrosis.

Mauz Asghar, College of Medicine, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada. E-mail: imp826@usask.ca

Introduction: Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the hamate is an exceptionally rare condition, with limited cases reported in the literature. This case highlights the successful management of idiopathic hamate AVN using core decompression and a vascularized pedicle bone flap from the distal radius based on the 4–5 extensor compartmental artery (ECA).

Case Report: A 45-year-old construction worker presented with chronic left wrist pain of 2 years’ duration following minor trauma. Despite conservative treatment with cast immobilization, the symptoms persisted. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed AVN of the hamate, prompting surgical intervention involving core decompression and a 4–5 ECA vascularized bone flap supplemented with cancellous autograft. Post-operative follow-up demonstrated significant functional improvement, grip strength restoration, and successful revascularization confirmed by imaging.

Conclusion: This report demonstrates the successful use of the 4–5 ECA-based vascularized bone flap technique in managing hamate AVN, as well as a literature review of 13 previously described cases.

Keywords: Avascular necrosis, hamate, vascularized bone flap.

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the hamate is an exceptionally rare condition, with only a few cases documented in the literature [1]. The hamate, an important carpal bone for midcarpal load transmission and wrist stability, is particularly vulnerable to ischemia due to its unique vascular anatomy. The proximal pole relies entirely on intraosseous circulation, while the hook receives a limited blood supply (primarily from branches of the ulnar artery, that is, the deep branch of the palmar arterial arcade and the dorsal intercarpal arch) with minimal anastomosis, predisposing these regions to AVN following trauma or repetitive stress [2].

Patients with hamate AVN (hook or body) typically present with ulnar-sided wrist pain exacerbated by gripping or loading activities. These symptoms can mimic other conditions, such as triangular fibrocartilage complex (TFCC) injuries or pisotriquetral arthritis, complicating diagnosis [1]. Radiographs are often normal in the initial stages, necessitating advanced imaging modalities, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) for early detection and staging [3]. MRI with gadolinium contrast is recommended for optimal diagnostic sensitivity, as it enhances differentiation between viable and necrotic bone, particularly in early-stage AVN [4].

Management of hamate AVN is challenging due to its rarity and the lack of standardized treatment protocols. Initial conservative measures, such as immobilization, are often unsuccessful, necessitating surgical intervention. Options include core decompression, non-vascularized bone grafting, and vascularized pedicled bone flaps, which have shown promise in restoring blood supply and improving outcomes [1, 2, 5-7]. Among vascularized grafts, medial femoral condyle (MFC) and medial femoral trochlea (MFT) flaps have been successfully utilized in other carpal AVN cases, such as Kienböck’s disease and scaphoid non-union [8], but there are currently no reported cases of MFC/MFT use in hamate AVN [8]. In addition, non-pedicled vascularized bone grafts, such as those harvested from the iliac crest or distal radius, have been employed in other bone AVN cases [9], but their efficacy in hamate AVN remains unknown.

This report presents a case of idiopathic hamate AVN successfully treated with core decompression and a vascularized pedicle bone flap based on the 4–5 extensor compartmental artery (ECA). The case highlights the diagnostic challenges, limitations of non-operative management, and the potential of vascularized bone grafting techniques to yield excellent functional and radiographic outcomes.

Patient history and presentation

A 45-year-old right-hand dominant, otherwise healthy male construction worker presented with a 2-year history of chronic, progressive left wrist pain following minor trauma. The patient described striking his palm with a phone, which resulted in initial discomfort that worsened over time. He denied systemic symptoms, previous wrist trauma, or corticosteroid use.

The pain was localized to the ulnar aspect of the wrist and exacerbated by activities involving gripping or repetitive wrist motion. Conservative measures, including analgesics and a wrist splint, provided no relief.

Examination findings

Physical examination revealed tenderness over the hook of the hamate and pain with resisted flexion of the fourth and fifth digits. Grip strength on the affected side was markedly reduced compared to the contralateral side (14 kg, 33% difference), with a 9 kg key pinch bilaterally. Range of motion was moderately restricted, with active wrist flexion of 75° and extension of 60°, compared to 85° and 65°, respectively, on the right side. Neurovascular assessment, including two-point discrimination and motor strength testing, was normal. There was no tenderness on palpation of the scapholunate interval, anatomic snuffbox, fovea, or scaphoid tubercle. Provocative extensor carpi ulnaris testing was negative. The pre-operative Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) score was 52.5.

Imaging studies

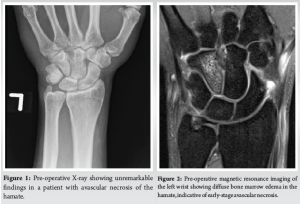

Initial radiographs were unremarkable (Fig. 1), consistent with early-stage AVN. MRI revealed diffuse bone marrow edema within the hamate, consistent with AVN (Fig. 2). No associated fractures or significant degenerative changes were noted. In addition, there was no evidence of tendon abnormalities or pathology at insertion sites. Gadolinium-enhanced imaging was not utilized in this case, though its use remains at the clinician’s discretion, as there is no established gold standard in the literature regarding its necessity for diagnosing hamate AVN.

Management

A 2-months trial of cast immobilization and activity restriction was initiated. However, symptoms persisted, with worsening functional impairment. As such, we elected to proceed with surgical intervention.

Surgical intervention

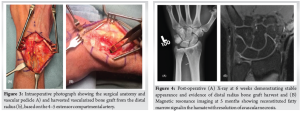

In March 2021, the patient underwent surgical intervention consisting of reconstruction of the hamate via core decompression and a vascularized pedicled bone flap based on the 4-5 ECA from the distal radius, supplemented with cancellous autograft from the same site. A 10 cm incision was made along the ulnar border of the fourth extensor compartment. The extensor retinaculum was incised with a step-cut for later repair. The retinacular flaps were carefully mobilized with care to protect the underlying compartmental vascular system – particularly the 5th ECA, which usually runs in close proximity to the radial border of the 5th compartment and the 4–5 septum. Synovectomy was performed for the third, fourth, and fifth extensor compartments to address any inflammatory changes. A 1 × 1 cm vascularized bone flap was planned from the dorsal ulnar aspect of the radius along the floor of the 4th extensor compartment just ulnar to Lister’s tubercle and avoiding the sigmoid notch. The 4th and 5th ECAs were carefully identified and exposed throughout the incision, extending distally to the level of the hamate. The anterior interosseous artery was ligated proximal to the take-off of the 4th and 5th ECAs, and the pedicle was circumferentially mobilized allowing great excursion while preserving blood supply to the bone flap through retrograde flow through the 5th ECA extending into antegrade flow through the 4th ECA. After this, the bone flap was carefully elevated using a combination of Kirschner wire corticotomy, a 1mm burr, and osteotomes. The hamate was exposed through subperiosteal dissection without violating the midcarpal joint, and a dorsal cortical window was created centrally. Sclerotic bone was removed through core decompression using a high-speed burr under continuous irritation and curettage. The base of the defect was first filled with cancellous autograft, and the harvested vascularized bone flap was subsequently securely press-fit into the prepared site. The extensor retinaculum was then repaired to restore native tendon compartments, and the wound was closed with interrupted nylon sutures. Post-operatively, the wrist was immobilized with a forearm-based volar wrist splint in slight wrist extension.(Fig. 3).

Post-operative course

At 3 weeks post-operative, a wound check and suture removal were completed, and a circumferential cast was placed without complications. Early digital range of motion was encouraged. By 6 weeks post-surgery, the patient reported pain resolution with no residual swelling of the digits, wrist, or forearm. Follow-up X-rays at 6 weeks (Fig. 4) showed a stable appearance with evidence of the previous distal radius bone flap harvest. Physical examination at 6 weeks revealed normal neurovascular status, ability to make a full composite fist, full thumb opposition, and restored rotational range of motion in the wrist. Wrist flexion-extension arc was limited due to immobilization and formal hand therapy was initiated (at 6 weeks) and progressed as tolerated. Strength, conditioning, and weight-bearing were added after an additional 4 weeks and progressed as symptoms allowed.

Follow-up MRI (Fig. 4) was completed at 5 months post-operatively, which demonstrated a largely reconstituted fatty enhanced signal in the hamate, resolved AVN, and a small, non-displaced healing interface on the lateral and dorsal aspects of the hamate, consistent with expected post-operative changes.

By 1 year, the patient continued to be pain-free and had regained symmetric wrist extension (65°), pronation (85°), and grip strength (32 kg) greater than the contralateral side (29 kg). Persistent modest deficits on the affected side included wrist flexion of 70° (vs. 85°) and supination of 80° (vs. 88°). DASH score at final follow-up was 6.7.

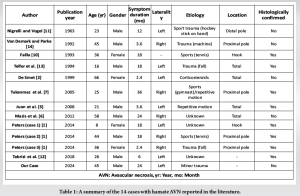

A literature search was conducted on PubMed using the following keywords: “Avascular necrosis” AND “hamate”. These terms yielded relevant case reports and reviews, forming the foundation for this analysis of 13 cases [1,2,5-7,10-14] including the present report (Tables 1 and 2).

AVN of the hamate remains exceedingly rare, with only 13 cases reported in the literature. Analysis reveals a slight male predominance (9 males, 4 females), with an average age of 34.5 years (range: 8–66 years). This demographic distribution suggests that AVN of the hamate affects a wide age range, differing slightly from the younger, more physically active population often associated with AVN of other carpal bones.

The etiology of hamate AVN is diverse, with trauma or repetitive stress identified as the leading cause in 7 of the 13 cases (53.85%). Examples include sports injuries (i.e., tennis, hockey, gym) and occupational hazards. Other contributing factors included corticosteroid use in systemic conditions, such as lupus (one case, 7.69%) and idiopathic causes (three cases, 23.08%) [2]. The unique vascular anatomy of the hamate, particularly the proximal pole’s dependence on intraosseous circulation and the hook’s limited vascular supply, predisposes these regions to ischemia after trauma or stress, as supported by Moran et al. [15] and Peters et al. [16].

Symptom duration before diagnosis ranged from 2 to 36 months, with an average of 12 months (median = 15, interquartile range = 3.6–18). The delay in diagnosis underscores the diagnostic complexity of hamate AVN, as clinical presentations, including ulnar-sided wrist pain exacerbated by gripping or load bearing, often mimic other conditions, such as TFCC injuries [17]. Physical examinations frequently revealed tenderness over the hook of the hamate, although findings were not consistently reported.

Plain radiographs, commonly used as an initial diagnostic tool, often fail to detect early AVN changes, highlighting the critical role of MRI [1,13] . MRI demonstrated bone marrow edema, sclerosis, and ischemic changes in early stages, making it the most sensitive diagnostic modality [1,13] . CT scans proved valuable for evaluating structural integrity in advanced disease or pre-surgical planning [6]. The literature does not establish a definitive gold standard regarding the use of gadolinium-enhanced MRI for diagnosing hamate AVN. While some studies suggest that gadolinium improves sensitivity and specificity [1], others successfully diagnosed AVN using non-contrast MRI [6,7]. Juon et al. [5] reported that gadolinium-enhanced imaging highlighted microvascular changes in later-stage disease, but its routine use remains debatable. Given these findings, the decision to use gadolinium should be based on clinical suspicion and institutional imaging protocols, as no universal consensus exists on its necessity.

Treatment strategies varied widely across the 13 cases, reflecting the lack of standardized protocols. Non-operative management, such as immobilization, was attempted in three cases (23.08%) but consistently failed to provide lasting relief or prevent disease progression in the published literature [1,7,12] . Surgical interventions were utilized in 13 cases, highlighting the predominant reliance on operative management for hamate AVN. Excision of the hook was successfully employed in cases where the hook was exclusively affected; this approach provided complete pain resolution and functional recovery [1,10]. Core decompression with vascularized bone grafting showed promising results in 5 (38.46%) cases [6,7,12,13], including ours. By directly restoring blood supply and decompressing ischemic regions, this approach led to excellent outcomes, including pain resolution, grip strength restoration, and radiographic revascularization. Meanwhile, although debridement and fusion were effective for pain relief in advanced cases (7, 53.85%), this approach often resulted in more substantial reductions in wrist motion, indicating its limitations in restoring function [6,7] .

Our case demonstrated the efficacy of combining core decompression with a vascularized pedicle bone flap based on the ECA for hamate AVN without associated arthritis. At 11 months post-operatively, the patient achieved pain resolution, substantial grip strength improvement (from 14 kg to 32 kg), and MRI evidence of revascularization. Although MFC flaps and non-vascularized bone grafts are employed in other carpal AVN lesions, they are still uncommon in hamate AVN to date. MFC flaps are technically challenging, have donor-site morbidity, but are highly vascular and have not been described for hamate lesions. The 4–5 ECA vascularized bone flap technique has shown particular promise in revascularizing ischemic bone. First described for lunate AVN (Kienböck’s disease) [15], this method leverages the robust vascular supply of the fourth and fifth extensor compartments, providing consistent revascularization and structural support. Non-vascularized grafts are less complicated but can fail in poorly vascularized bone. Conversely, the 4–5 ECA flap offers a reliable, local, and technically possible alternative with revascularization efficacy, as in this case. Since AVN of the hamate is as uncommon as it is, the 4–5 ECA procedure seems to offer a balance between efficacy and surgical convenience [15]. Compared to simpler procedures, such as core decompression alone or excision arthroplasty, the 4–5 ECA vascularized graft involves greater surgical complexity, longer operative time, and potentially higher resource utilization. However, it offers the advantage of biological reconstruction and vascular restoration. In rare conditions, such as hamate AVN, the decision must balance technical demands with long-term functional goals [15].

Moran et al. [15] highlighted the technique’s advantages, including a large-diameter pedicle and long pedicle length, which allow for enhanced blood flow and improved graft viability. Similarly, Peters et al. [16] demonstrated its effectiveness in treating AVN of the capitate, reporting improved pain and function at follow-up. These findings underscore the versatility and reliability of the 4–5 ECA technique across different carpal bones, particularly when a long pedicle is required to reach the distal carpal row.

It is important to acknowledge that the precise mechanism by which hamate vascularity is restored following surgery has not been fully elucidated. Certainly, several factors may contribute, including core decompression of both the hamate and distal radius, non-vascularized cancellous bone grafting, and pedicled vascularized bone grafting [12,18,19]. Although a reductionist approach to the procedure may be considered (i.e., core decompression alone), given the limitations in the literature and the rarity of this condition, it may be recommended to continue with a more comprehensive approach, which has shown promise in the available published literature.

Post-operative outcomes varied depending on disease severity and the surgical approach. The use of vascularized bone flaps, particularly the 4–5 ECA technique, consistently led to favorable results, including pain relief, functional restoration, and radiographic evidence of revascularization. Excision of the hook of hamate also demonstrated excellent outcomes in localized AVN cases [1]. In contrast, debridement and fusion approaches were reserved for more advanced cases, and as such, associated with variable outcomes, often sacrificing motion to achieve pain relief.

Despite these promising results, the long-term viability of the vascularized graft remains a potential concern, particularly regarding the risk of partial graft resorption, insufficient revascularization, or recurrent ischemia. While early post-operative imaging often confirms initial graft integration, long-term follow-up remains crucial to monitor for disease recurrence or delayed collapse. Moran et al. [15] reported that 77% of patients who underwent 4–5 ECA vascularized bone grafting for Kienböck’s disease demonstrated revascularization on MRI at a mean follow-up of 20 months, reinforcing the importance of serial imaging for evaluating graft viability. Similarly, Peters et al. [1] highlighted that persistent pain and partial non-union were observed in some cases despite surgical intervention, suggesting the necessity of long-term surveillance for graft failure or recurrent AVN.

Standardized imaging protocols are not well established, but most studies recommend MRI with contrast (to assess graft perfusion and integration) or CT scans (to evaluate structural integrity) at 3, 6, and 12 months post-operatively [20-22]. Radiographic improvement, including reconstitution of fatty marrow on MRI, has been a reliable indicator of successful graft revascularization [23]. However, persistent low signal intensity on T1-weighted MRI may suggest delayed bone healing or partial graft failure [24], warranting extended follow-up. Further research is needed to establish optimal imaging intervals and define criteria for long-term surgical success in vascularized bone graft procedures for hamate AVN.

Limitations

This report has several limitations. First, histological confirmation of AVN and post-treatment viability was not performed, as diagnosis and follow-up were based solely on MRI. Gadolinium-enhanced sequences, which could have provided more definitive perfusion data, were not used due to institutional protocol. In addition, imaging follow-up was limited to 5 months; longer-term evaluation is needed to assess graft durability and detect late complications, such as collapse or arthritis. Functional outcomes were measured using the DASH score and grip strength; however, more wrist-specific tools, such as PRWE or the Mayo Wrist Score were not employed. The positive outcome in this case may, in part, be attributed to the patient’s absence of major comorbidities, such as diabetes, smoking, or peripheral vascular disease, which are known to impair healing. However, it is important to note that the patient was somewhat deconditioned and not in peak overall health. Moreover, while he adhered to the formal immobilization protocol, he remained relatively active outside of his cast, suggesting partial non-compliance with broader activity restrictions. As such, although not a high-risk case, this patient does not represent the ideal surgical candidate, and the outcome may not be directly generalizable to populations with more complex medical profiles or lower adherence. The physical therapy regimen was individualized and progressed as tolerated, limiting reproducibility across patients. Finally, the literature review was narrative rather than systematic, which may have introduced selection bias. Resource utilization and surgical complexity, while acknowledged, were not formally analyzed and remain important considerations when choosing among treatment options.

AVN of the hamate is a rare and challenging condition, often linked to trauma or repetitive stress, with a slight male predominance. Delayed diagnosis, averaging 15 months, underscores the need for heightened clinical suspicion and early use of advanced imaging, such as MRI. Among treatment options, vascularized bone grafting, particularly using the 4–5 ECA, has demonstrated excellent outcomes in revascularization and functional recovery. This report highlights the diagnostic challenges, limitations of non-operative management, and the potential of vascularized bone grafting techniques to yield excellent functional and radiographic outcomes.

This report emphasizes the critical importance of early recognition and advanced imaging in diagnosing AVN of the hamate, a rare and thus possibly underreported condition. It highlights the effectiveness of the 4–5 ECA pedicled vascularized bone flap technique in achieving revascularization, pain relief, and functional restoration. By presenting the details of this surgical approach with excellent outcomes, this case serves as a valuable reference for clinicians managing similar cases, guiding them toward optimal diagnostic and treatment strategies.

References

- 1.Peters SJ, Verstappen C, Degreef I, Smet LD. Avascular necrosis of the hamate: three cases and review of the literature. J Wrist Surg 2014;3:269-74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.De Smet L. Avascular necrosis of multiple carpal bones. A case report. Chir Main 1999;18:202-4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reinus W, Conway W, Totty W, Gilula L, Murphy W, Siegel B, et al. Carpal avascular necrosis: MR imaging. Radiology 1986;160:689-93. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Afshar A, Tabrizi A. Avascular necrosis of the carpal bones other than Kienböck disease. J Hand Surg Am 2020;45:148-52. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Juon BH, Treumann TC, von Wartburg U. [Avascular necrosis of the hamate--case report]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir 2008;40:201-3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mazis GA, Sakellariou VI, Kokkalis ZT. Avascular necrosis of the hamate treated with capitohamate and lunatohamate intercarpal fusion. Orthopedics 2012;35:e444-7. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tukenmez M, Percin S, Tezeren G. Aseptic necrosis of the hamate: a case report. Hand Surg 2005;10:115-8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Saruhan S, Savran A, Yıldız M, Şener M. Reconstruction of proximal pole scaphoid non-union with avascular necrosis using proximal hamate: A four-case series. Hand Surg Rehabil 2021;40:744-8. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aldridge JM, Urbaniak JR. Avascular necrosis of the femoral head: role of vascularized bone grafts. Orthop Clin North Am 2007;38:13-22. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Failla JM. Hook of hamate vascularity: vulnerability to osteonecrosis and nonunion. J Hand Surg Am 1993;18:1075-9. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nigrelli RF, Vogel, H. Spontaneous tuberculosis in fishes and in other cold-blooded vertebrates with special reference to Mycobacterium fortuitum Cruz from fish and human lesions. New York: Zoologica: Zoological Society 1963;48:131–44. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tabrizi A, Afshar A, Aidenlou A. Avascular necrosis of the hamate treated with core decompression: a case report. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2018;43:778-80. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Telfer JR, Evans DM, Bingham JB. Avascular necrosis of the hamate. J Hand Surg Br 1994;19:389-92. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Demark RE, Parke WW. Avascular necrosis of the hamate: a case report with reference to the hamate blood supply. J Hand Surg Am 1992;17:1086-90. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran SL, Cooney WP, Berger RA, Bishop AT, Shin AY. The use of the 4+ 5 extensor compartmental vascularized bone graft for the treatment of Kienböck’s disease. J Hand Surg Am 2005;30:50-8. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peters S, Degreef I, De Smet L. Avascular necrosis of the capitate: report of six cases and review of the literature. J Hand Surg Eur Vol 2015;40:520-5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahmad F, Torres-Gonzalez L, Sabet A, Simcock X, Fernandez JJ. Avascular Necrosis of an Adolescent Distal Radius: A Literature Review. J Hand Surg Glob Online 2023;5:379-81. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mehrpour SR, Kamrani RS, Aghamirsalim MR, Sorbi R, Kaya A. Treatment of Kienböck disease by lunate core decompression. J Hand Surg Am 2011;36:1675-7. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rellan I, Gallucci GL, Boretto JG, Donndorff AG, Zaidenberg EE, De Carli P. Metaphyseal core decompression and anterograde fixation for scaphoid proximal pole fracture nonunion without avascular necrosis. J Wrist Surg 2019;8:416-22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson SE, Steinbach LS, Tschering-Vogel D, Martin M, Nagy L. MR imaging of avascular scaphoid nonunion before and after vascularized bone grafting. Skeletal radiology 2005;34:314-20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox M, Wang D, Chhabra A. Accuracy of enhanced and unenhanced MRI in diagnosing scaphoid proximal pole avascular necrosis and predicting surgical outcome. Skeletal radiology 2015;44:1671-8. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karapinar L, Gurkan A, Kacar S, Polat O. Post-transplant femoral head avascular necrosis: a selective investigation with MRI. Annals of Transplantation 2007;12:27. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willems WF, Alberton GM, Bishop AT, Kremer T. Vascularized bone grafting in a canine carpal avascular necrosis model. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 2011;469:2831-7. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lazik A, Landgraeber S, Claßen T, Kraff O, Lauenstein TC, Theysohn JM. Aspects of postoperative magnetic resonance imaging of patients with avascular necrosis of the femoral head, treated by advanced core decompression. Skeletal radiology 2015;44:1467-75. [Google Scholar]