Congenital absence of the ACL, though extremely rare, should be considered for differential diagnosis in young patients with bilateral knee instability and no history of trauma.

Dr. Nikita Jajodia, Joint Replacement, Sports Injury and Trauma, Department of Orthopaedics, Marengo Asia Hospitals, Gurugram, Haryana, India. E-mail: jalannikita@gmail.com

Introduction: Congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), first reported by Giorgi in 1956 is an extremely rare condition. The prevalence of this condition is reported to be around 0.017/1,000 live births. This congenital anomaly can present in isolation or be associated with other skeletal malformations, including fibular hemimelia, congenital femoral deficiencies, and hip dysplasia. Congenital ACL deficiency may often go undiagnosed in early life. Others will eventually experience symptoms due to the long-term effects of knee instability that can lead to chronic knee pain, particularly in the medial knee and patellofemoral compartments, and may predispose individuals to early-onset osteoarthritis. As the condition is extremely rare and can occur with or without associated deformities, there is no single treatment of choice for the condition.

Case Report: We herein report a case of bilateral isolated congenital absence of ACL in a 24-year-old young woman who presented to us with the chief complaints of pain in the right knee for the past 2 years and the left knee for the past 10 months.

Conclusion: Although good outcomes with conservative management in individuals without symptomatic instability have been reported, surgeons advocate ACL reconstruction in cases presenting with symptomatic instability.

Keywords: Chronic anterior cruciate ligament tear, congenital absence of anterior cruciate ligament, anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction.

Congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), first reported by Giorgi in 1956 [1], is an extremely rare condition. The prevalence of this condition is reported to be around 0.017/1,000 live births [2]. This congenital anomaly can present in isolation or be associated with other skeletal malformations, including fibular hemimelia, congenital femoral deficiencies, and hip dysplasia [3]. Congenital ACL deficiency may often go undiagnosed in early life. Others will eventually experience symptoms due to the long-term effects of knee instability that can lead to chronic knee pain, particularly in the medial knee and patellofemoral compartments, and may predispose individuals to early-onset osteoarthritis. As the condition is extremely rare and can occur with or without associated deformities, there is no single treatment of choice for the condition. Although good outcomes with conservative management in individuals without symptomatic instability have been reported, surgeons advocate ACL reconstruction in cases presenting with symptomatic instability [4].

We herein report a case of bilateral isolated congenital absence of ACL.

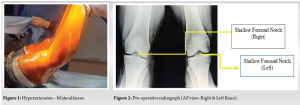

A 24-year-old young woman presented to us with the chief complaints of pain in the right knee for the past 2 years and the left knee for the past 10 months. She had difficulty in walking and climbing stairs. There was no history of injury to the knees or history suggestive of an inflammatory pathology, which ruled out the two most common reasons for musculoskeletal pain in young adults. She did not report the presence of any constitutional symptoms as well. We performed a physical examination of both knees. The knees appeared normal in inspection, and there were no associated skin changes. There was no joint line tenderness. The range of motion in both knees was −20–120°. There was 20° hyperextension in both knees (Fig. 1).

Tests performed for knee instability is mentioned in Table 1.

Investigations

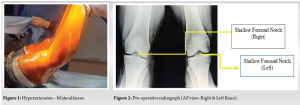

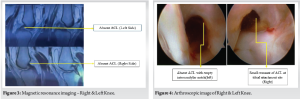

Suspecting an ACL tear in both knees, we ordered radiographs of the knees. Apart from a shallow intercondylar notch, the radiographs appeared grossly normal (Fig. 2). The patient had undergone magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of her knees elsewhere. The MRI findings reported bilateral deficiency of ACL in both knees (Fig. 3). Although the physical examination and MRI findings diagnosed the case to be bilateral chronic ACL tear on both sides, the history was far from confirming a traumatic ACL tear.

We also sent her routine blood investigations which were essentially normal.

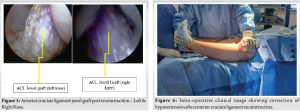

We therefore decided to do a diagnostic arthroscopy of both the knees to have a direct look inside her knees. The ACLs of both the knees were completely absent. There was only a small visible remnant of ACL at the tibial attachment in both the knees (Fig. 4). The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), the medial femoral condyle, medial tibial condyle, medial meniscus, lateral femoral condyle, lateral tibial condyle, and lateral meniscus were found to be normal. These findings confirmed that this was a case of bilateral isolated congenital absence of ACL.

Surgery

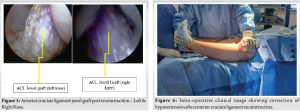

We obtained consent from the patient to perform arthroscopic reconstruction of ACL in both knees using the peroneus longus graft through standard anteromedial and anterolateral portals. After the graft for the ACL reconstruction was harvested from the peroneus longus tendon, it was passed through a jewel ACL synthetic graft sheath (Fig. 5) and the final graft sizes were as follows:

- Right knee:

- Graft diameter: 8.5 mm

- Graft length: 28 mm

- Left knee:

- Graft diameter: 9 mm

- Graft length: 29 mm

Tunnel details

- Right femoral tunnel: Positioned at the 10 o’clock position, dimensions: 38 × 4.5 mm (proximal)/28 × 8.5 mm (distal)

- Right tibial tunnel: At the footprint, dimensions: 45 × 8.5 mm

- Left femoral tunnel: Positioned at the 2 o’clock position, dimensions: 36 × 4.5 mm (proximal)/30 × 8.5 mm (distal)

- Left tibial tunnel: At the footprint, dimensions: 45 × 9 mm.

The graft was successfully passed and flipped with an Endo-Button. Interference screws of size 10 × 28 mm was used to fix the graft to the tibial tunnel.

The knee was cycled to ensure proper graft tension, and there was no impingement. Reverse Lachman testing was not performed. The tension in the graft was found to be optimal. Both knees demonstrated a 5-degree hyperextension, which was considered acceptable (Fig. 6).

The patient was put on rehabilitation exercises from the next day. The patient ambulated with a walker on the 1st day after surgery. During the course of stay in the hospital, the patient was given intravenous antibiotics, analgesics, anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy, and other supportive treatment.

It is important to understand the embryological development of the ACL in cases of congenital absence. The development of the cruciate ligaments begins early in fetal development. By approximately 8 weeks of gestation, the formation of the cruciate ligaments becomes visible, initially as a cellular condensation. Over time, this condensation evolves, with an increase in collagen formation, which contributes to the structural integrity of the ligament [5]. The collateral ligaments, which are crucial for knee stability, begin to form around 7 weeks of gestation. By 9 and a half weeks, the ACL is well developed, marking a critical stage in the formation of the knee’s ligamentous structures [5]. Literature reports that the congenital absence of ACL can be associated with other musculoskeletal deficiencies and intra-articular anomalies. Manner et al. examined the radiographic features of congenital longitudinal deficiencies of lower limbs and studied 34 knees, focusing on the aplasia of one or both cruciate ligaments using MRI and tunnel view radiographs [6]. Three types of cruciate ligament dysplasia were identified: Type I, with partial femoral notch closure and tibial eminence hypoplasia, and hypoplastic or absent ACL and normal PCL; Type II, with accentuated changes and additional PCL hypoplasia; and Type III, with absent femoral notch and tibial eminence, and complete aplasia of both cruciate ligaments. Interestingly, the development of the menisci coincides with the maturation of the ACL, beginning around 9 and a half weeks. This synchronized development of ligaments and menisci underscores the complex and coordinated process of knee joint formation during early fetal development. This fact probably explains why some cases have associated anomalies of other intra-articular structures along with an absent ACL. The case report that we present here belongs to type I category according to Manner et al. [6]. A series by Frikha et al. [7] described the congenital absence of ACL in eight cases of the same family, essentially pointing toward a genetic predisposition in such cases. However, further research is needed to study in detail regarding the change in the genetic make-up of the individuals that present with this condition. Most of the cases with this condition do not show any symptoms, at least in the early years of life. The reason could be the compensation that is provided by the adjacent muscles stabilizing the knee [8]. When instability is absent, conservative management provides good results. When they present, they usually complain of pain in the knee, instability while walking, and difficulty in climbing stairs. Patients become symptomatic once the compensation by the muscle forces cannot match the stability needed for the knee. Once the signs of instability manifest, ACL reconstruction using a graft is recommended to restore stability and normal kinematics of the knee [8]. In the absence of ACL, the forces acting across the knee change the dynamics leading to increased degeneration of the joint causing early arthritis. In an isolated ACL deficiency without any associated deformities and alteration of intra-articular anatomy, reconstruction with a graft is usually straightforward with or without a need to perform notchplasty [9]. Such a picture is usually encountered in Manner Type I. In Types II and III, where there could be significant alteration of bony anatomy, namely hypoplasia of the lateral femoral condyle, increased tibial slope, rounded posterior femoral condyle, and absence of the foot prints, reconstruction of ACL could be quite arduous [7]. In-depth pre-operative planning using MRI and radiographs is needed before proceeding with the surgery. The aim of the treatment is the same as that of routine ACL surgery, i.e., to provide stability to the knee by restoring normal knee kinematics and to prevent early arthritis [10].

Bilateral chronic ACL insufficiency due to congenital absence is a rare entity. Despite the absence of the ACL, the patients are able to compensate for the instability during early life, which is why symptoms develop only later in early or late adulthood. The diagnosis needs a high degree of suspicion and is confirmed through a combination of clinical examination, radiographic imaging, and diagnostic arthroscopy. As seen in this patient, once symptomatic instability arises, ACL reconstruction is necessary to restore knee stability and prevent further degeneration, which could lead to early-onset osteoarthritis. The findings of this case reinforce the importance of early diagnosis and careful surgical planning in managing congenital ACL deficiency, particularly when associated with other structural anomalies. While conservative management may be effective in individuals presenting without instability, surgical intervention is often required when instability manifests. Future studies and genetic research may provide further insights into the underlying mechanisms of this condition and its potential familial or hereditary links. Ultimately, the goal of treatment remains to restore normal knee kinematics and prevent early joint degeneration.

Congenital absence of the ACL, though rare, can present as chronic bilateral instability in adulthood. A high index of suspicion, thorough evaluation, and timely intervention are crucial to restore knee stability and prevent early degenerative changes.

References

- 1.Giorgi B. Morphologic variations of the intercondylar eminence of the knee. Clin Orthop 1956;8:209-17. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Chahla J, Pascual-Garrido C, Rodeo SA. Ligament reconstruction in congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament: A report of two cases. HSS J 2015;11:177-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Noble J. Congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament associated with a ring meniscus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1975;57:1165-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Gabos PG, El Rassi G, Pahys J. Knee reconstruction in syndromes with congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament. J Pediatr Orthop 2005;25:210-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Uhthoff HK. The Embryology of the Human Locomotor System. Germany: Springer-Verlag; 1990. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Manner HM, Radler C, Ganger R, Grill F. Dysplasia of the cruciate ligaments: Radiographic assessment and classification. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:130-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Frikha R, Dahmene J, Hamida RB, Chaieb Z, Janhaoui N, Ayeche ML. Congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament: Eight cases in the same family. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot 2005;91:642-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Sonn KA, Caltoum CB. Congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament in monozygotic twins. Int J Sports Med 2014;35:1130-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Lee JJ, Oh WT, Shin KY, Ko MS, Choi CH. Ligament reconstruction in congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament: A case report. Knee Surg Relat Res 2011;23:240-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Chahla J, Pascual-Garrido C, Rodeo SA. Ligament Reconstruction in Congenital Absence of the Anterior Cruciate Ligament: A Report of Two Cases. HSS J. 2015 Jul;11(2):177-81. doi: 10.1007/s11420-015-9448-6. Epub 2015 May 17. PMID: 26140039; PMCID: PMC4481253. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]