Achieving length, axis, rotation, and articular compression are essential pre-requisites before application of a locking plate as an external fixator without spanning the joint for a good functional outcome.

Dr. Aliasger Moaiyadi, Department of Orthopedics, Topiwala National Medical College, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: aliasger_pro07@outlook.com

Introduction: Compound tibial fractures are a common injury due to high velocity trauma and its management is always a challenge to the surgeon due to increased chances of infection, non-union, poor blood supply, and potential risk of amputation. Unilateral external fixator, though the gold standard, had many problems related to patient compliance and complications, such as joint stiffness. We aim to evaluate the effectiveness of the metaphyseal locking plate applied as an external fixator in managing the compound tibia fracture.

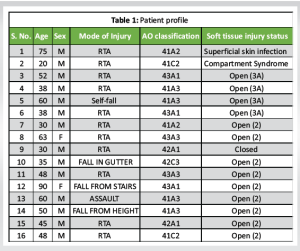

Materials and Methods: We treated 16 cases of tibia fractures (proximal, diaphyseal, distal) with soft tissue injury using a metaphyseal locking plate as an external fixator and followed them for a period of 9 months to assess fracture union, complication, functional outcome, and patient compliance. Regular ankle knee range of movement was done and radiographs were taken to assess union and alignment of the limb.

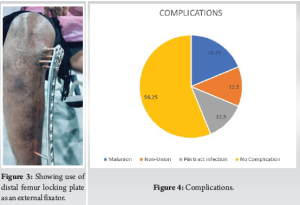

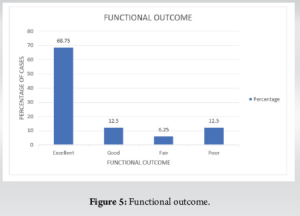

Results: The mean time to bony union was 19.7 weeks and the standard deviation is 5.75. Two cases of non-union, 3 cases of malunion, and 11 cases of union in proper alignment were achieved. 11 patients had excellent (68.75%), 2 had good functional results (12.5%), 1 had a fair functional outcome (6.25%), and 2 cases had poor functional outcome (12.5%).

Conclusion: Metaphyseal locking plate can be an effective alternative to unilateral external fixator in terms of patient compliance, achieving good knee-ankle range of motion, fracture union, and thereby achieving good functional outcome.

Keywords: Compound fracture tibia, Metaphyseal locking plate as external fixator, external fixator.

Open tibial fractures caused by high-energy trauma are usually accompanied by severe soft tissue damage [1]. Proximal tibial fractures with soft tissue injury require external fixation for wound management and initial stabilization of the fracture [2]. However, a conventional external fixator is difficult to apply, in such cases without spanning the joint. Joint-spanning fixators in periarticular or articular compound tibia fractures are bulky and uncomfortable for the patients. The patients encounter problems with daily activities, such as clothing. The cumbersome frame also blocks the movement of the contralateral extremity while walking. When the conventional external fixator spans the joint for a longer period of time, there are unavoidable complications, such as muscle atrophy and joint stiffness [3]. It is a well-established fact that the locking plates behave as an internal fixator and can be applied in a bridging mode to provide sufficient interfragmentary motion and secondary healing by callus formation. Hence, some clinicians have used locking plates applied externally as an external fixator and reported satisfactory results [4]. The application of a plate as an external fixators in such periarticular fractures may obviate the necessity to apply joint-spanning fixator and may result in early rehabilitation of the patient and prevent stiffness of joint. Thus, early range of joint motion, better patient daily activities and comfort, rigid fixation, and easy access to the wounds are the advantages of the locking plate as an external fixator over the conventional fixator [5]. The locking plate as an external fixator due to its locking screw head function also provides axial and angular stability at the fracture site and thus forms a distinctive construction of plate, screw, and bone [6]. It remained an off-label treatment [7]. The aim of our study is to determine whether application of a locking plate as an external fixator in periarticular fractures instead of using a joint-spanning conventional fixator produce sufficient stability to maintain the fracture reduction and thereby achieve union of the fracture with a good functional outcome.

This observational study was conducted from February 2022 to May 2024 in a rural hospital in central India. It included all open tibial fractures that met the specified criteria.

Inclusion criteria

- Diaphyseal, Articular and Juxta-articular tibial fractures

- Compound fractures

- Age more than 18 years

- Soft tissue injury and poor skin condition.

Exclusion criteria

- Compound fractures with bone loss

- Neurovascular injury

- Ipsilateral fracture to the distal femur and the shaft femur

- Ipsilateral patella fracture

- Ipsilateral fracture to tarsals and metatarsals

- Pre-existing injury or any pathology involving the knee and ankle

- Any pre-existing neurological disorder affecting the lower extremity.

Pre-operative assessment and management protocol

All patients were examined for injuries and primarily stabilized using skeletal traction, limb elevation on a BB splint, IV fluids, blood transfusions, and vasopressors if necessary. The patient was given anti-tetanus prophylaxis and started on intravenous antibiotics covering both gram-positive and gram-negative organisms. The wound was thoroughly cleaned and debrided, followed by stay sutures if possible. After stabilization of the vitals of the patient, fracture anatomy was evaluated through X-rays in both anteroposterior and lateral views. A computed tomography scan was taken when needed. Fracture was classified according to the AO classification and soft tissue injury in open fracture was assessed with Gustilo-Anderson Classification.

Surgical technique

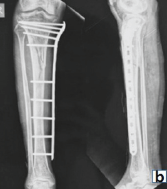

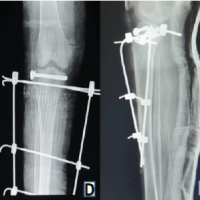

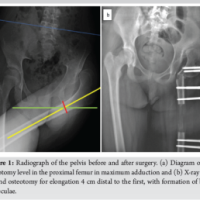

Under spinal anesthesia, all patients underwent surgery after the subsidence of swelling. Under C-arm guidance, by applying traction and manipulation, a trial of reduction is given. The fibula is fixed first when needed to maintain the length. The reduction of articular fragments through manipulation with bone spikes or bone tamps through the wound site when possible or through small stab incisions. After achieving the reduction, it was held with temporary K-wires. Articular block is then fixed with diaphysis with the metaphyseal locking plates (either proximal tibia hockey plate or distal femur plate of 4.5 mm) (Fig. 1-3) applied as an external fixator either from the medial site or from the lateral site, avoiding the wound so that proper wound care can be taken. The reduction is done by applying manual traction and manipulation to prevent angulation or shortening. Sometimes, bone spikes or bone holding clamps were used to hold the reduction. The position of the plate is checked under C-arm and held temporarily over the skin with the help of K-wires passing through the holes in the plate meant for K-wire passing. The final reduction is checked under C-arm before fixing the plate. A block is used to maintain the distance of two fingers from the skin. The proximal screws are fixed first by applying stab incisions on the skin. We tried to put at least 3–4 proximal screws of 4.5 mm. Similarly, at least 3 bi-cortical screws were fixed in the diaphysis through the plate.

The principle we followed for the surgery is to get the reduction first and holding the reduction temporarily, and then applying the locking plate under traction to maintain the limb length.

After debridement of the wound, primary closure was done except in two cases where fasciotomy was done and skin grafting was required. Wound swab was sent for culture and sensitivity. Antibiotics were adjusted based on the culture and sensitivity report. After surgery, patients began knee and ankle-toe movements the following day and were taught non-weight-bearing mobilization with the help of a walker. Static quadriceps and hamstring exercises were also initiated. Pin site dressing done every other day with the use of betadine. Partial weight bearing started at 1 month with the help of support. Full weight bearing was permitted once there were radiological and clinical signs of fracture union. The fracture is fully healed when a bridging callus appears in at least four cortices on the radiograph and there is no pain or tenderness in the fracture area. Plate removal was done at this stage.

Patients were monitored at a monthly interval up to 9 months.

We assessed the following indicators:

- Presence of infection (deep infection and screw tract infection) deep wound infection was defined as the presence of local inflammatory symptoms, such as redness erythema or swelling, presence of purulent discharge, and positive bacterial culture. Screw tract infection was diagnosed from the presence of discharge around the screw site and redness [8].

- Time to union: Normal healing within 6 months; delayed union for healing after 6 months.

- Non-union: Defined as the absence of healing progression over 3 consecutive months on serial radiographs after 9 months of injury.

- Limb length discrepancy.

- Knee and ankle range of motion.

- Malunion: Defined as malalignment of more than 5° in any plane on full-length tibia radiograph, shortening >1 cm, and distal fragment rotation >15° or step-off of the articular surface of more than 2 mm on anteroposterior (AP) and lateral radiographs.

- Union is defined as the presence of a mature bridging callus of 4 cortices on both AP and lateral plane and painless and full weight bearing. Time to union is counted from the initial trauma, irrespective of intermittent surgery [8].

Functional results were evaluated based on the following clinical criteria [9,10].

- The presence of a limp

- Stiffness of the knee or the ankle

- Pain

- Soft tissue sympathetic dysfunction

- Inability to perform previous activities of daily living.

- An excellent result is the absence of all of the mentioned criteria

- A good result is the presence of one of the clinical criteria

- A fair result is the presence of two of the clinical criteria

- A poor result is the presence of more than three of the five clinical.

There were 14 male patients and 2 female patients; 7:1 ratio. The mode of injury was RTA in 11 cases (68.75%), significant fall in 4 cases (25%), and assault in 1 case (6.25%) (Table 1). The time between injury (admission) and definitive surgery was 4.8 days on average (range 1–12 days). There were 3 cases of closed fracture, out of which 2 had compartment syndrome and 1 had superficial skin infection, 4 cases of Gustilo-Anderson 3A fractures, and 9 cases of type 2 Gustilo-Anderson fractures (Table 1). The mean bone healing time was 19.7 weeks with a standard deviation (SD) of 5.75 (range 12–36 weeks). Malrotation was not clinically relevant in any cases. Limb-length discrepancy was less than 1cm in all patients. Average time to full weight bearing was 20.5 weeks (12–32 weeks). The average time of fixator removal was 20.5 weeks SD 5.03 (12–32 weeks). The Mean Anteroposterior angulation was 3° (0–7°), mean mediolateral angulation was 4° (0–15°). Malunion was noted in 3 out of 16 cases (18.75%), non-union was seen in 2 cases (12.5%), and union in acceptable alignment 11 out of 16 cases (68.75%).

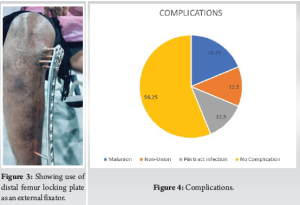

The average knee range of motion was flexion 107.8° (70–135°). There was no fixed flexion deformity at the knee joint. Full extension was achieved in all cases. The ankle dorsi flexion was on average 10.6° (0–15°) and plantar flexion was 35° (0°–40°). There were no cases with equinus deformity at the ankle. There were no cases of deep infection. Pin tract infection was seen in 2 patients out of 16 cases (12.5%). There was no loosening or failure of fixation seen. 11 patients had excellent (68.75%), 2 had good functional results (12.5%), 1 had a fair functional outcome (6.25%), and 2 cases had poor functional outcome (12.5%).

The management of compound tibia fracture is always a challenge to the surgeon due to its poor blood supply in the distal part, the medial aspect of the bone being subcutaneous, the chances of skin necrosis, infection, and chances of potential amputation are high. The tibia fracture is generally due to violent trauma accompanied by severe soft tissue damage [11]. The proximal tibial fractures are associated with compartment syndrome and neurovascular issues. Conventionally, external fixators have been the cornerstone in damage control orthopedics for managing contaminated open fractures and also closed fractures with severe soft tissue injuries. It is helpful for soft tissue recovery, stabilization of the fracture, and preservation of blood supply to the fractured bone [12]. By virtue of its design, external fixators produce appropriate interfragmentary motion that leads to callus formation and thereby secondary bone healing [13]. These compound tibial fractures have been successfully treated using two-stage reconstruction method, which involves initial stabilization with a bridging external fixator for soft tissue recovery and thereafter definitive reconstruction of the articular surface and metadiaphyseal fractures. This method has successfully decreased the complication rates [14].

Due to increased cost and duration associated with the two-stage traditional reconstruction, external fixators have been either used alone or with limited internal fixation as a definitive treatment by some orthopedic surgeons, and success of this method has been reported in the literature [15-18]. Even then, there are many disadvantages of external fixators as frames are bulky and cumbersome to carry and cause difficulty in clothing and also sometimes cause difficulty in walking when the frame is near the knee area, as it tends to touch the opposite limb. When fixators are used across the joint for stabilization of intra-articular or juxta-articular fractures for a long time, it leads to muscle atrophy and joint stiffness [3].

To overcome this problem, various studies have demonstrated the use of locking metaphyseal plates for the treatment of compound fractures of tibia [3,5,9,19].

Kloen and Tulner et al. also studied the use of locking plate as an external fixator for managing compound tibia fracture and reported a good union rate [20,21]. A biomechanical comparative study of axial and torsional stiffness between locking compression plate as a external fixator and unilateral external fixator by Ang et al. concluded that Locking plate as a external fixator maybe a viable and attractive alternative to unilateral external fixator as it is a low profile design which is more acceptable to the patient and not a compromise on axial and torsional stiffness compared to unilateral external fixator [22]. A finite element analysis comparing external locking plate fixation and conventional external fixation by Blažević et al. showed external locking plate fixation to be more flexible than conventional external fixation and thereby promote secondary bone healing. The main advantage behind the use of a metaphyseal locking plate as an external fixator is that the construct does not cross the knee or ankle joint and mobilization could be started early, and the patient could achieve acceptable knee and ankle motion and functional recovery [23]. One study where locking compression plate was used as a fixator after removal of the Ilizarov frame following distraction in cases of tibial bone defects caused by fracture-related infections to aid in rehabilitation and alleviate the psychological burden of patients for keeping a bulky frame [24]. Bangura et al. in their study divided their 44 patients into two groups and fixed their tibial fractures with a locking plate external fixator and a combined frame external fixator, respectively. They concluded that patients with a locking plate as an external fixator had shorter hospitalization time, reduced re-operation rate, better quality of life, and better recovery [25]. In our study, we could achieve an average knee range of motion of extension 7.18° to flexion 107.8 and average ankle range of motion of 10.6° dorsiflexion (0–15°) and 35° of plantar flexion. The low-profile design made it comfortable for the patient to wear clothing and do assisted ambulation. In our study, there were 12.5% non-union, 18.75% malunion, and 68.75% union in accepted alignment. The union rate is comparable to other studies in the literature [3,7,10]. There were no major complications in our study. We had 2 cases of non-union (12.5%), 3 cases of malunion (18.75%), and 2 cases of pin-tract infection (12.5%) (Fig. 4).

On assessment of functional outcome, 11 patients had excellent outcome (68.75%), 2 had good functional outcome (12.5%), 1 had fair functional outcome (6.25%), and 2 cases had poor functional outcome (12.5%) (Fig 5). The results of our study are comparable in the literature by various authors, such as Qiu et al. [3], Ma et al. [7]. In our study, there was no case of limb length discrepancy more than 1 cm, even in those with fracture comminution, as during fracture fixation, we kept the contralateral leg clean and draped by the side and applied traction to the affected limb during fixation to match with the length of the opposite limb. In over-distraction, some amount of shortening was accepted but not more than 1 cm. Two cases that had non-union had bone loss and a gap between the fracture extremity, which was managed later with intramedullary nail and grafting. However, shortening was not accepted at the initial fixation. One problem with the locking plate was that the trajectory of the locking screws could not be changed and the position of the plate could not be modified after the screws were placed, so initial accurate reduction of the articular surface before placing the locking plate as an external fixator is a must. This could be achieved by using pointed reduction clamps, then elevating the articular surface using bone tamps by giving small incisions under the C-arm and holding the reduction by multiple K-wires and then applying the plate either on the medial or lateral side. While placing the plate on the lateral side, it has to be kept in mind that large-size locking screws should be made available due to more soft tissue bulk on the lateral side. Both metaphyseal locking plates of the distal femur, distal tibia, and proximal tibia were used in our study, depending on the fracture geometry and location. The length of the plate should be such that at least you are able to put 3 bicortical screws distally. We had no incidence of screw breakage or implant loosening, even when we started partial weight bearing with support in all cases at 4 weeks.

Limitation of the study

- Not a comparative study

- Limited sample size.

Metaphyseal locking plate can be an effective alternative to traditional unilateral external fixator as a definitive management for treating intraarticular and periarticular fractures of the tibia with poor skin condition, as the construct is stable and low profile, and well tolerated by the patient, even if used for a long duration. Soft tissue management is also possible with the locking plate in situ. The only disadvantage is that accurate articular reduction is a must before placing the plate and dynamization of the fracture cannot be done, which is possible with a unilateral external fixator.

Locking plate as an external fixator is an alternative cost-effective option in case of compound tibia fracture instead of using a joint-spanning or conventional external fixator or ring fixator. Only after getting the reduction, the plate has to be applied externally and contact of the metaphysio-diaphyseal region in alignment has to be maintained, as dynamization cannot be done afterward. The effectiveness of this plate is easy rehabilitation of the patient in terms of range of motion at the joint, good acceptance and compliance with the plate as it is low profile, which the patients can carry with ease and cover up under their clothing.

References

- 1.Mills WJ, Nork SE. Open reduction and internal fixation of high-energy tibial plateau fractures. Orthop Clin North Am 2002;33:177-98. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Egol KA, Tejwani NC, Capla EL, Wolinsky PL, Koval KJ. Staged management of high-energy proximal tibia fractures (OTA types 41): The results of a prospective, standardized protocol. J Orthop Trauma 2005;19:448-55. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Qiu XS, Yuan H, Zheng X, Wang JF, Xiong J, Chen YX. Locking plate as a definitive external fixator for treating tibial fractures with compromised soft tissue envelop. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014;134:383-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Zhang J, Ebraheim NA, Li M, He X, Liu J. One-stage external fixation using a locking plate: Experience in 116 tibial fractures. Orthopedics 2015;38:494-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Ma CH, Wu CH, Yu SW, Yen CY, Tu YK. Staged external and internal less-invasive stabilisation system plating for open proximal tibial fractures. Injury 2010;41:190-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Cronier P, Pietu G, Dujardin C, Bigorre N, Ducellier F, Gerard R. The concept of locking plates. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2010;96:S17-36. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Ma CH, Wu CH, Jiang JR, Tu YK, Lin TS. Metaphyseal locking plate as an external fixator for open tibial fracture: Clinical outcomes and biomechanical assessment. Injury 2017;48:501-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Teraa M, Blokhuis TJ, Tang L, Leenen LP. Segmental tibial fractures: An infrequent but demanding injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:2790-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Ma CH, Tu YK, Yeh JH, Yang SC, Wu CH. Using external and internal locking plates in a two-stage protocol for treatment of segmental tibial fractures. J Trauma 2011;71:614-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Ma CH, Wu CH, Tu YK, Lin TS. Metaphyseal locking plate as a definitive external fixator for treating open tibial fractures--clinical outcome and a finite element study. Injury 2013;44:1097-101. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Perry CR, Evans LG, Rice S, Fogarty J, Burdge RE. A new surgical approach to fractures of the lateral tibial plateau. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:1236-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Schmal H, Strohm PC, Jaeger M, Südkamp NP. Flexible fixation and fracture healing: Do locked plating ‘internal fixators’ resemble external fixators? J Orthop Trauma 2011;25:S15-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Bottlang M, Doornink J, Fitzpatrick DC, Madey SM. Far cortical locking can reduce stiffness of locked plating constructs while retaining construct strength. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:1985-94. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1999;13:78-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Marsh JL, Smith ST, Do TT. External fixation and limited internal fixation for complex fractures of the tibial plateau. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:661-73. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Watson JT, Moed BR, Karges DE, Cramer KE. Pilon fractures. Treatment protocol based on severity of soft tissue injury. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;375:78-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Hao ZC, Xia Y, Xia DM, Zhang YT, Xu SG. Treatment of open tibial diaphyseal fractures by external fixation combined with limited internal fixation versus simple external fixation: A retrospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019;20:311. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Albushtra A, Mohsen AH, Alnozaili KA, Ahmed F, Aljobahi YM, Mohammed F, et al. External fixation as a primary and definitive treatment for complex tibial diaphyseal fractures: An underutilized and efficacious approach. Orthop Res Rev 2024;16:75-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Ma CH, Yu SW, Tu YK, Yen CY, Yeh JJ, Wu CH. Staged external and internal locked plating for open distal tibial fractures. Acta Orthop 2010;81:382-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Kloen P. Supercutaneous plating: Use of a locking compression plate as an external fixator. J Orthop Trauma 2009;23:72-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Tulner SA, Strackee SD, Kloen P. Metaphyseal locking compression plate as an external fixator for the distal tibia. Int Orthop 2012;36:1923-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Ang BF, Chen JY, Yew AK, Chua SK, Chou SM, Chia SL, et al. Externalised locking compression plate as an alternative to the unilateral external fixator: A biomechanical comparative study of axial and torsional stiffness. Bone Joint Res 2017;6:216-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Blažević D, Kodvanj J, Adamović P, Vidović D, Trobonjača Z, Sabalić S. Comparison between external locking plate fixation and conventional external fixation for extraarticular proximal tibial fractures: A finite element analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 2022;17:16. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Kadier X, Liu K, Shali A, Hamiti Y, Wang S, Yang X, Keremu A, et al. Locking compression plate as a sequential external fixator following the distraction phase for the treatment of tibial bone defects caused by fracture-related infection: Experiences from 22 cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024;25:1088. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Bangura ML, Luo H, Zeng T, Wang M, Lin S, Chunli L. Comparative analysis of external locking plate and combined frame external fixator for open distal tibial fractures: A comprehensive assessment of clinical outcomes and financial implications. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:962. [Google Scholar | PubMed]