The failure of metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty underscores the critical need for a national joint registry in the Caribbean to ensure early detection of implant failures, enhance patient safety, and improve clinical outcomes.

Dr. Marlon M Mencia, Department of Clinical Surgical Sciences, Orthopaedic Surgery Unit, Port of Spain General Hospital, Port of Spain, Trinidad. E-mail: mmmencia@me.com

Introduction: The predicted advantages of better survivorship and function from metal-on-metal (MoM) total hip arthroplasty (THA) systems introduced in the early 2000s did not materialise. Instead, national registry data indicated high failure rates, and these devices were quickly withdrawn from the market. With over 1 million MoM articulations implanted worldwide, there is a need for close follow-up and surveillance of the at-risk population.

Case Report: A 54-year-old woman presented with a painful right MoM hip arthroplasty. Serial radiographs demonstrated progressive migration of the acetabular shell with extensive osteolysis. After medical clearance, the patient underwent a successful isolated acetabular revision. The bone defects were filled with bone substitute, and the acetabulum was reconstructed using a metal cage and a cemented all-polyethylene cup.

Conclusion: MoM THA is associated with a high failure rate and the need for early revision. An unverified number of these implants were used in Trinidad in 2009, leaving patients at risk for premature failure. In the Caribbean, the medical devices industry is largely under-regulated, exposing the patient to unnecessary risks. The formation of a national joint registry administered through the Caribbean Association of Orthopedic Surgeons could provide outcome data, identify early implant failures, and improve patient safety.

Keywords: Metal on metal, hip arthroplasty, registry, surveillance, revision, Caribbean.

The emergence of large-diameter metal-on-metal (MoM) total hip arthroplasty (THA) into the market promised improved durability and enhanced function. This expectation was based on the assumption that hard bearings were more wear-resistant and the larger heads created a more naturally stable joint. Predictably, this new technology was enthusiastically embraced by surgeons, and in the United States, MoM THA comprised 35% of all THAs implanted between 2005 and 2007 [1]. Such passion for new technology was reflected in a survey of The American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons members, which revealed that 68% of surgeons routinely used MoM bearings [2]. However, amid this rapid expansion, reports of early implant failure and pseudotumor formation were causing concern among groups of arthroplasty surgeons [3,4]. With longer follow-up periods, the clinical picture became clearer and more disturbing, with unacceptably high failure rates of MoM THA that eventually led to its withdrawal from the market. Several studies reported early and difficult revision of these implants with substantial soft-tissue damage and pseudotumor formation. Pseudotumor, or what is now known as adverse reaction to metal debris (ARMD), was noted to be the main reason for revision in a series of MoM THA with 82.4% survivorship at 10.9 years [5]. Similarly, Aguado-Maestro et al. found 88.5% survivorship at 7.3 years in 26 patients with a Recap-M2a-Magnum THA [6]. In one of the largest studies involving 1,450 patients with a Recap-M2a-Magnum THA, the authors reported a 69% hip-specific survival for any ARMD event at 14 years [7]. In light of these worrisome reports, the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency in the United Kingdom issued a safety alert in 2010 [8]. This was closely followed by the recall of several MoM THA systems, including the much publicised DePuy articular surface replacement hip replacement [9]. The overall result has been a global halt on using MoM-bearing surfaces for THA and a strong recommendation for post-market surveillance of patients with these devices [10]. A national joint registry monitors the performance of different implants and provides an early warning system about implants which may be failing prematurely. In Sweden, the national joint registry has successfully identified poorly performing implants, which allowed surgeons to choose the best products for arthroplasty and significantly reducing the revision burden [11]. ARMD is the leading cause of failure in MoM THA, and is often clinically silent, requiring active surveillance for early detection. To the best of our knowledge, there is no active national joint registry within the English-speaking Caribbean countries, leaving an undocumented section of the population with these implants at risk of failure and revision. Our report describes the first revision arthroplasty of a MoM THA in the Caribbean and underlines the need for a national joint registry in the region.

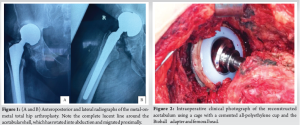

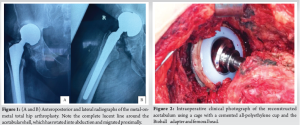

The patient is a 54-year-old Afro-Caribbean woman who, 12 years ago, underwent a right MoM THA (ReCap-M2a-Magnum, Biomet) for primary osteoarthritis. She presented to the clinic with severe hip pain and deteriorating function to the point that she was now unable to work. Initial radiographs showed migration of the acetabular shell, and we recommended revision surgery. However, due to financial constraints and the COVID-19 pandemic, the operation was delayed for 3 years. Pre-operative laboratory blood work showed normal serum C-reactive protein and erythrocyte sedimentation rate. There are no local facilities for serum metal ion levels, and the cost of a pre-operative metal artefact reduction sequence magnetic resonance imaging was prohibitive. As a proxy, we requested an ultrasound examination of the hip, which showed no soft-tissue masses. Compared with previous films, new radiographs demonstrated ongoing superior migration of the acetabular shell and progressive osteolysis, although the femoral stem remained stable (Fig. 1). In light of these findings, we thought that isolated acetabular revision was the most appropriate surgical strategy.

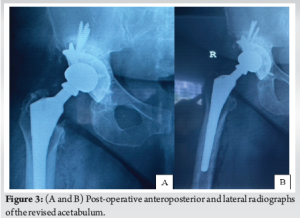

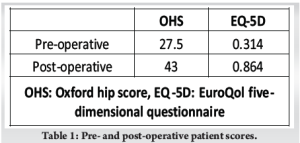

We incorporated the old incision and used a modified Hardinge approach to the hip. The soft tissues appeared healthy with minimal embedded metal debris, and there was no evidence of infection. The femoral head was easily removed, and the Morse taper was in good condition without signs of trunnionosis. After removing the acetabular shell, the exposed bony floor showed only minor cavitary defects, and the walls and columns were intact. We prepared the acetabulum in routine fashion, but without the benefit of morselized allograft, using a bone graft substitute (Medbone® Biomaterials, Portugal) to fill the defects. The bone graft substitute was contained by an acetabular cage (Contour, Smith and Nephew) secured with multiple screws. An all- polyethylene cup was cemented in place with Palacos® R (Heraeus Medical, Germany) cement, and a Bioball® adapter and femoral head (Merete, Germany) compatible with the Type one taper on the retained femoral stem, impacted in place (Fig. 2). The hip was reduced and cycled through its range of movement to ensure stability. The patient recovered well, and post-operative radiographs were satisfactory (Fig. 3). At the 2-year follow-up visit, the patient is delighted with her function, reporting only mild hip pain and has returned to full-time work, as shown in Table 1.

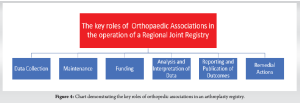

MoM THA failed to deliver on its promise of improved function and longevity, and in reality, this class of medical device has largely been a disaster. The main reason for early failure is the intense inflammatory response to metal debris, which can often cause extensive soft-tissue necrosis and osteolysis. Such effects precipitate the development of solid and cystic periprosthetic lesions. These lesions resemble malignant tumors and were previously called pseudotumors but are now better described and collectively known as ARMD. Several studies have reported the prevalence of ARMD after ReCap-M2a-Magnum THA to range from 39 to 54% [5,12,13]. As might be expected, there is a proportionally high rate of failure, with medium-term survivorship (5–10 years) ranging between 88.5 and 91.1% and long-term survivorship (>10 years) dropping to 82.4% [5,6,7,14] When failure is attributed solely to ARMD, survivorship falls even further, with one study reporting hip-specific survival of 69% at 14 years [7]. It is therefore not surprising that concerns about the high failure rate have prompted the call for close surveillance of these implants. The index case reported here was performed in Trinidad, and to the best of our knowledge, the ReCap-M2a-Magnum THA was the only large-head MoM THA ever used on the island. We estimate that approximately 100 operations using this implant were performed in Trinidad over 18 months, from 2009 in six hospitals. This case prompted us to poll the Caribbean Association of Orthopaedic Surgeons (TCOS) membership to determine if other surgeons in the region had a similar experience. To our surprise, none of the surgeons reported revising a ReCap-M2a-Magnum THA or having a patient with this implant awaiting revision. While on face value this may seem encouraging, one must also consider that ARMD may be asymptomatic until failure is imminent. Unfortunately, without a joint registry and a surveillance program to monitor and track patients, the true picture remains obscure. Establishing a joint registry is a critical component of any contemporary arthroplasty service. A registry records, analyses, and reports on the outcomes of joint replacement surgery and may be the first sign of a poorly performing implant. Sweden established the first orthopedic registry for knee arthroplasty in 1975, and since then, we have witnessed the development of over 15 national joint registries for hip and knee replacement worldwide [15]. Despite the expense involved in maintaining a registry, the exponential growth of joint replacement has resulted in calls, largely from the orthopedic community, for registries to be established in low and middle-income countries [16,17]. In this regard, significant progress has already been made; in 2009, a national joint registry was established in Malawi, one of the poorest countries in the world [18]. Their recently reported 10-year results for THA found good outcomes comparable to many developed countries with low rates of revision, infection, and dislocation [19]. The success observed in Malawi would not have been possible without the full support of the national orthopedic association. As practicing orthopedic surgeons, we are the major contributors supplying the registry with the data that is needed for analysis. It is therefore not surprising that most registries are managed by the local orthopedic associations and supported by government funding [15]. Orthopedic associations fulfil key roles in the functioning of a national joint registry and, to a large extent, are responsible for its success or failure Fig. 4. For example, the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Registry was established in 1979 and is maintained by the Swedish Orthopaedic Association. The registry is credited with improving clinical practice and lowering the revision burden, which has resulted in significant cost savings [20-22]. By comparison, the Finnish registry that is run by the National Agency of Medicine has achieved limited success, and the revision rate that remains 50% higher than in Sweden [23]. It is widely accepted that direct surgeon involvement is responsible for the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Registry’s unprecedented success and durability. This observation by the Finnish authorities has led to a closer relationship between the orthopedic association and the joint registry in an attempt to improve clinical outcomes [23]. These alliances are consistent with the growing trend of orthopedic associations actively managing the day-to-day activities of registries [20]. As the official representative body for orthopedic surgeons working within the English-speaking Caribbean region, TCOS has a major role to play in forming a joint registry. In 2023, members of TCOS committed to supporting the establishment of a regional arthroplasty register, and at the recently concluded 2024 Annual Scientific Meeting, attendees were apprised of its progress.

National joint registries improve the quality of care and the safety of patients undergoing hip and knee replacements. The data derived from these registries are used to improve clinical decision-making, inform public health policy, and build a value-based health-care system. The worldwide exponential growth of joint replacement has widened into the Caribbean, a region that is particularly vulnerable to the introduction of inferior implants. Several studies have shown that joint registries can successfully monitor unproven technology, identify poor-performing implants, and ultimately reduce the revision burden. Joint registries are an integral part of any contemporary health-care system, playing a critical role in safeguarding the public. However, active participation of all arthroplasty surgeons is central to its success. That being the case, TCOS, through its leadership role and collective expertise, is eminently qualified to play a pivotal role in establishing a regional arthroplasty registry.

The high failure rate of MoM THA is often clinically silent and can lead to extensive soft tissue damage and osteolysis, resulting in complex revision surgery. A national joint registry can monitor implant performance, detect early failures, and improve patient safety, aligning the Caribbean with global best practices in orthopedic care.

References

- 1.Bozic KJ, Ong K, Lau E, Kurtz SM, Vail TP, Rubash HE, et al. Risk of complication and revision total hip arthroplasty among medicare patients with different bearing surfaces. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2357-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Berry DJ, Bozic KJ. Current practice patterns in primary hip and knee arthroplasty among members of the American association of hip and knee surgeons. J Arthroplasty 2010;25:2-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW, National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: Analysis of data from the national joint registry of England and wales. Lancet 2012;379:1199-204. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Pandit H, Glyn-Jones S, McLardy-Smith P, Gundle R, Whitwell D, Gibbons CL, et al. Pseudotumours associated with metal-on-metal hip resurfacings. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2008;90:847-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Van Lingen CP, Ettema HB, Bosker BH, Verheyen CC. Ten-year results of a prospective cohort of large-head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: A concise follow-up of a previous report. Bone Jt Open 2022;3:61-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Aguado-Maestro I, Cebrián Rodríguez E, Herrero EP, Vegas FB, Miranda MO, García NF, et al. Midterm results of magnum large head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol (Engl Ed) 2018;62:310-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Pietiläinen S, Linnovaara A, Venäläinen MS, Mäntymäki H, Laaksonen I, Lankinen P, et al. Median 10-year whole blood metal ion levels and clinical outcome of recap-M2a-magnum metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2022;93:444-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency. Medical Device Alert: All Metal-on-Metal (MoM) Hip Replacements; 2017. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5954ca1ded915d0baa00009b/mda-2017-018-final.pdf [Last accessed on 2022 Aug 31]. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Bolognesi MP, Ledford CK. Metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty: Patient evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015;23:724-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.US Food and Drug Administration. Metal on Metal Hip Implants. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/implants-and-prosthetics/metal-metal-hip-implants [Last accessed on 2024 Aug 31]. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Herberts P, Malchau H. Long-term registration has improved the quality of hip replacement: A review of the swedish THR register comparing 160,000 cases. Acta Orthop Scand 2000;71:111-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Bosker BH, Ettema HB, Boomsma MF, Kollen BJ, Maas M, Verheyen CC. High incidence of pseudotumour formation after large-diameter metal-on-metal total hip replacement: A prospective cohort study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2012;94:755-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Mokka J, Junnila M, Seppänen M, Virolainen P, Pölönen T, Vahlberg T, et al. Adverse reaction to metal debris after recap-M2A-magnum large-diameter-head metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty. Acta Orthop 2013;84:549-54. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Koutalos AA, Kourtis A, Clarke IC, Smith EJ. Mid-term results of recap/magnum/taperloc metal-on-metal total hip arthroplasty with mean follow-up of 7.1 years. Hip Int 2017;27:226-34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Kolling C, Simmen BR, Labek G, Goldhahn J. Key factors for a successful national arthroplasty register. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:1567-73. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Holt JA, Aird JJ, Gollogly JG, Ngiep OC, Gollogly S. Developing a sustainable hip service in cambodia. Hip Int 2014;24:480-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Davies PS, Graham SM, Maqungo S, Harrison WJ. Total joint replacement in sub-saharan Africa: A systematic review. Trop Doct 2019;49:120-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Lubega N, Mkandawire NC, Sibande GC, Norrish AR, Harrison WJ. Joint replacement in Malawi: Establishment of a national joint registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:341-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Graham SM, Howard N, Moffat C, Lubega N, Mkandawire N, Harrison WJ. Total hip arthroplasty in a low-income country: Ten-year outcomes from the national joint registry of the malawi orthopaedic association. JB JS Open Access 2019;4:e0027. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Gomes LS, Roos MV, Takata ET, Schuroff AA, Alves SD, Camisa A Jr. Advantages and limitations of national arthroplasty registries. The need for multicenter registries: The rempro-SBQ. Rev Bras Ortop 2017;52:3-13. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Malchau H, Herberts P, Ahnfelt L. Prognosis of total hip replacement in sweden. Follow-up of 92,675 operations performed 1978-1990. Acta Orthop Scand 1993;64:497-506. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Malchau H, Herberts P, Eisler T, Garellick G, Söderman P. The swedish total hip replacement register. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84-A Suppl 2:2-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.Labek G, Janda W, Agreiter M, Schuh R, Böhler N. Organisation, data evaluation, interpretation and effect of arthroplasty register data on the outcome in terms of revision rate in total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2011;35:157-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]