Management of hemorrhagic blisters following total knee replacement.

Dr. Dhinesh Nadarajan Latha, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Bhaarath Medical College and Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: dhineshmmc@gmail.com

Introduction: Skin blisters occur due to increased shear forces at the dermo-epidermal junction. They are classified as clear and hemorrhagic blisters. Blisters occur due to trauma, compartment syndrome, and vascular deficits. We present a case report of hemorrhagic blister formation following bilateral total knee replacement.

Case Report: A 64-year-old male with bilateral advanced osteoarthritis of the knees underwent bilateral total knee replacement in the same sitting. Surgery was done under strict aseptic precautions and tourniquet control. The procedure went uneventfully. Postoperatively, on the 2nd day, the patient developed massive hemorrhagic blisters around the operated site in both legs. Doppler scans showed no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. The blisters were managed by intravenous antibiotic coverage and soft, non-adherent collagen dressings. The blisters healed and reepithelialized by 3 weeks. A range of motion exercise was initiated on the 2nd post-operative day, as tolerated. At the final follow-up of 1 year, the patient had satisfactory Oxford Knee Scores.

Conclusion: Non-adhesive dressings, prophylactic intravenous antibiotics, and effective rehabilitation are the keystones in the management of patients with hemorrhagic blisters following total knee replacement.

Keywords: Blister, knee replacement, hemorrhage.

Skin blisters are fluid-filled sacs that arise in the dermal–epidermal junction as a result of tissue trauma, leading to increased microscopic shear forces at this juncture. On physical examination, these are tense blood or clear fluid-filled bullae overlying markedly swollen and edematous soft tissue. Blisters occur secondary to trauma, compartment syndrome, infection, vascular insufficiency, and autoimmune conditions. Fracture blisters are a relatively uncommon complication of high-energy fractures, with an incidence of 2.9% [1]. We present a rare case report of a massive hemorrhagic blister following bilateral total knee replacement.

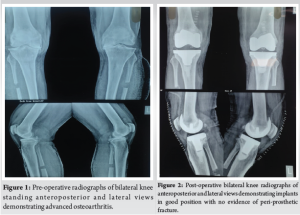

A 64-year-old male presented with complaints of bilateral knee pain and difficulty in activities of daily living for the past 5 years. He was a known diabetic on treatment. There was no history of any known allergies. Radiographs revealed bilateral end-stage osteoarthritis of the knee (Fig. 1). He had undergone a bilateral proximal fibular osteotomy 2 years prior for similar complaints. The patient was planned for bilateral total knee replacement after an anesthetist’s clearance. He was taken up for surgery under pneumatic tourniquet control. The tourniquet time for the right knee was 100 min, and for the left knee was 90 min. The skin was prepared with chlorhexidine and betadine solution. An OPSITE adherent dressing was applied over both knees. The medial parapatellar approach was used. Exactech cruciate retaining cemented implants were used in both knees. The surgery went uneventfully. Ranawat cocktail containing bupivacaine (0.5%), morphine sulphate (8 mg), epinephrine (1:1000), methylprednisolone acetate (40 mg), and cefuroxime (1.5 g) was infiltrated in the posterior capsule and gutters. The skin was closed with a suction drain inside, and a sterile dressing with cotton gauze piece and gamjee pad was done. The tourniquet was deflated once dressings were applied. Routine deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis injection enoxaparin 40 mg subcutaneously was started.

On post-operative day 2, a first wound inspection was performed with the removal of the drain. Multiple hemorrhagic blisters overlying erythematous skin, located adjacent to the surgical incision, were found over the left leg. Two to three clear, fluid-filled blisters overlying erythematous skin were found over the right leg (Fig. 3). Post-operative X-rays revealed a well-sited implant with no evidence of peri-implant fractures (Fig. 2). Distal pulses were intact postoperatively. Ultrasound venous Doppler images of both lower limbs showed no evidence of deep vein thrombosis. Biochemical markers of infection (C-reactive protein, TWC??) were unremarkable. What were the hemoglobin and platelet levels, and were any coagulation studies performed? Collagen dressings were applied over the blister site. Two to three large blisters were deroofed. Loose non-adherent dressings were done on both legs. Prophylactic intravenous cefuroxime 1.5 g was initiated and continued for 10 days to prevent infection. No further antibiotics were prescribed beyond this. Knee range of motion (ROM) exercises were initiated as tolerated by the patient. Full weight bearing was initiated on the 2nd post-operative day.

The limb edema started to subside by the 5th post-operative day, and the blisters started to epithelialize by the 7th post-operative day (Fig. 4). Suture removal was delayed up to the 16th post-operative day. The blistering eventually settled by 3 weeks duration without any evidence of deep infection (Fig. 5). On discharge, the patient had 90° flexion in both knees. One year follow-up showed good ROM (0 to 115 degree) an Oxford Knee Score of 46 value, which was acceptable, and no skin lesions.

Skin blistering occurs when the epidermis separates from the underlying dermis due to frictional forces on the skin. This leads to a breakdown of the skin’s protective barrier, increasing the risk of developing a periprosthetic joint infection [2]. Blisters are generally sterile in nature but may get contaminated after rupture, causing periprosthetic joint infection [3]. Histologically, blistering results from the separation of the epidermis (stratified squamous epithelium) from the vascular dermis, accompanied by the accumulation of edema fluid in the intervening space. Blisters are broadly classified into two main types: Hemorrhagic and clear. According to Giordano and Koval, hemorrhagic blisters involve a cleavage between the epidermis and dermis, leading to a longer average epithelialization time of 16 days. [4]. These findings are similar to our case, where it took almost 3 weeks for complete epithelialization of the blister. The causes of blisters in arthroplasty patients are multifactorial and related to age, obesity, venous insufficiency, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and alcohol. Farage et al. [5] identified various degenerative changes in aging skin, including vascular atrophy and the breakdown of dermal connective tissue, which compromise skin integrity. In patients with diabetes, the integrity of the dermis can be further weakened by glycosylation of collagen fibrils, lowering the threshold for suction-induced blister formation [6]. Our patient belongs to the elderly population and had diabetes mellitus as a contributory factor for the development of blisters. Surgical factors contributing to blister formation include increased tourniquet time, skin preparation, and wound dressings [7]. The intraoperative dressings, such as ioban, opsite, provide an adhesive antimicrobial drape during surgery. The removal of these tightly adherent drapes can be postulated to be a contributory factor in blister development by causing shearing at the dermo-epidermal junction. The evidence, however, supporting the use of these drapes as well as the risk of blister formation is not available in the literature. Intraoperative tourniquet time was appropriate for both knees. Adhesive dressings were not used in our post-operative wound dressing. There is no optimal treatment consensus for hemorrhagic blisters in the literature. Giordano and Koval [8] reported no significant differences in outcomes among various soft-tissue treatment approaches, including blister aspiration, blister deroofing, or leaving the blister intact and covering it with a loose dressing. In contrast, Madden et al. [9] demonstrated that occlusive non-adherent dressings were associated with significantly faster healing and reduced pain compared to semi-occlusive, antibiotic-impregnated dressings. We attempted to deroof 2–3 large blisters and applied collagen dressings over the blister site, followed by loose non-adherent dressings, which eventually epithelialized. Sharma et al. [10] have reported a similar case of blister formation following unilateral total knee replacement, which healed at 4 weeks, managed by intravenous antibiotics and deroofing. Halawi [11] has reported a case of fracture blister following knee replacement, which was also managed with prophylactic antibiotics. However, there was a delay in rehabilitation therapy due to pain and fear of losing the leg. Infection is one of the dreaded complications following hemorrhagic blisters. Fortunately, our patient had no evidence of superficial or deep infections due to effective prophylactic intravenous antibiotics. However, the exact role of antibiotics in infection control cannot be elucidated from a single patient. Pain due to blister formation was one of the major concerns post-surgeries as it limits effective rehabilitation of the patient. However, our patient did not need any escalation of analgesics and was on routine exercise protocol. With the resolution of blisters, he was able to effectively pursue ROM exercises and had a satisfactory Oxford Knee Score (46) at 1-year follow-up.

Massive hemorrhagic blisters can occur post-elective total knee arthroplasty. Adhesive intraoperative dressings, and tourniquet use can be contributory to blister formation in predisposed patients. Non-adhesive dressings, prophylactic broad-spectrum antibiotics, and effective rehabilitation protocols are the keystones in the management of such patients.

Massive hemorrhagic blisters following elective knee replacement surgery may be alarming to both patients and surgeons. However, with appropriate wound management, prophylactic antibiotics, and monitored rehabilitation, a good recovery is expected.

References

- 1.Varela CD, Vaughan TK, Carr JB, Slemmons BK. Fracture blisters: Clinical and pathological aspects. J Orthop Trauma 1993;7:417-27. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Clarke JV, Deakin AH, Dillon J, Emmerson S, Kinninmonth AW. A prospective clinical audit of a new dressing design for lower limb arthroplasty wounds. J Wound Care 2009;18:5-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Ousey K, Gillibrand W, Stephenson J. Achieving international consensus for the prevention of orthopaedic wound blistering: Results of a Delphi survey. Int Wound J 2013;10:177-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Giordano CP, Koval KJ. Treatment of fracture blisters: A prospective study of 53 cases. J Orthop Trauma 1995;9:171-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Farage MA, Miller KW, Berardesca E, Maibach HI. Clinical implications of aging skin: Cutaneous disorders in the elderly. Am J Clin Dermatol 2009;10:73-86. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Quondamatteo F. Skin and diabetes mellitus: What do we know. Cell Tissue Res 2014;355:1-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Gupta SK, Lee S, Moseley LG. Postoperative wound blistering: Is there a link with dressing usage? J Wound Care 2002;11:271-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Giordano CP, Koval KJ, Zuckerman JD, Desai P. Fracture blisters. Clin Orthop 1994;307:214-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Madden MR, Nolan E, Finkelstein JL, Yurt RW, Smeland J, Goodwin CW, et al. Comparison of an occlusive and a semi-occlusive dressing and the effect of the wound exudate upon keratinocyte proliferation. J Trauma 1989;29:924-30. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Sharma A, Subramanian P, Shah S, Remani M, Shahid M. Massive haemorrhagic blister formation following total knee arthroplasty. JRSM Open 2018 May 4;9(5):2054270418758569. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Halawi MJ. Fracture blisters after primary total knee arthroplasty. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2015;44:E291-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]