Non-traumatic atlantoaxial subluxation with vertebral artery anomalies requires thorough evaluation, individualized treatment, careful surgical planning, and ongoing research to optimize outcomes.

Dr. Pankaj Kandwal, Department of Orthopedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Rishikesh, Dehradun, Uttarakhand, India. E-mail: pankajkandwal27@gmail.com

Introduction: The overall incidence of vertebral artery (VA) variations is 2–3%, but among patients with congenital anomalies at the cranio-vertebral junction, it is 20%. Knowing these anomalies is important, if failed to recognize can lead to VA injury during surgery and subsequent cerebrovascular accidents.

Case Report: A 14-year-old boy presenting with progressive weakness of bilateral upper limb and lower limb was diagnosed as case of supra-axial cervical myelopathy due to congenital atlantoaxial subluxation with fenestration of VA and high-riding VA. The patient underwent posterior decompression and fusion using C1 lateral mass and C2 laminar screw rod construct.

Conclusion: A thorough evaluation of the anatomy of the craniovertebral joint is required in congenital pathologies, and a patient-specific treatment approach should be used. Surgical management can effectively alleviate symptoms and prevent complications, but careful consideration must be given to the risks and benefits of different surgical techniques.

Keywords: Atlanto-axial subluxation, vertebral artery, cranio-vertebral junction, congenital anomaly, cervical myelopathy.

Nontraumatic Atlantoaxial Subluxation (AAS) is one of the important conditions in adolescents presenting with torticollis and/or with signs of supra-axial cervical myelopathy. Recent neck infection, neck surgery, inflammatory disease, or congenital conditions of ligamentous laxity such as down syndrome, Marfan syndrome, or Klippel–Feil syndrome are some of the common etiologies for non-traumatic AAS. The congenital AAS cases may be associated with vertebral artery (VA) anomalies [1]. The incidence of variations in the course of VA is approximately 2–3% in the normal population and up to 20% in patients with congenital anomalies at the cranio-vertebral junction (CVJ) [2,3]. Knowing these anomalies is important, which if failure to recognize, can lead to VA injury during surgery and subsequent cerebrovascular accidents [4]. Here, we are presenting a rare case of congenital AAS with fenestration of VA and a high-riding VA managed with posterior decompression and fusion using C1 lateral mass and C2 laminar screws rod construct after mobilizing the VA during dissection for safe screw insertion.

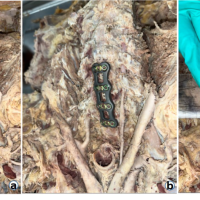

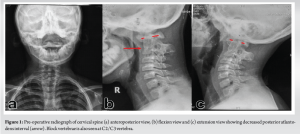

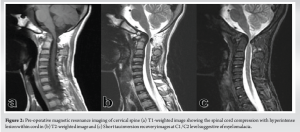

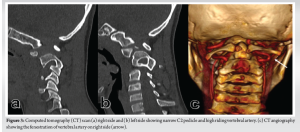

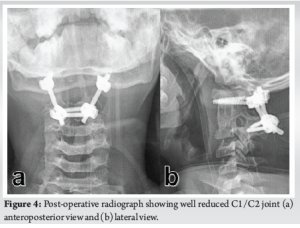

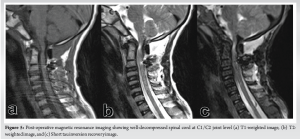

A 14-year-old boy presented to the spine clinic with progressive weakness of the bilateral upper limb, progressing to bilateral lower limb for the past 1.5 years following trivial trauma to the neck and with bowel and bladder incontinence for the past 1 year. At presentation, he was not able to stand without support, had increased tone (modified Ashworth grade 1) in bilateral upper and lower limbs, with functional motor power present and no sensory deficit in any of the dermatomes. On elicitation, both upper and lower limb reflexes were exaggerated. Exaggerated pectoralis reflex and presence of scapulohumeral reflex suggested a clinical diagnosis of supra-axial cervical myelopathy. On further evaluation, special signs such as Hoffman’s sign and grasp-release test were positive. Cervical spine radiograph showed atlantoaxial subluxation with decreased posterior atlanto-dens interval along with fusion of C2 and C3 vertebrae (Fig. 1). On magnetic resonance imaging cervical spine, thecal sac and spinal cord compression at the level of C1/C2 joint with no visible cerebrospinal fluid rim was noted (Fig. 2). 3D Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the cervical spine showed an incomplete anterior and posterior arch of the atlas with well-corticated bony fragments within the posterior arch defect. Note of fenestration of VA on right side and high-riding VA was also made (Fig. 3). A final diagnosis of supra-axial extradural compressive cervical myelopathy due to congenital atlantoaxial subluxation with anomalous VA (Nurick Grade 5) was made. The patient was planned for C1-C2 reduction and posterior instrumented fusion using C1 lateral mass and C2 laminar screws under intraoperative neuromonitoring. The patient was positioned prone on Mayfield, and a longitudinal midline approach from C1 to C3 was carried out, elevating the paraspinal muscle subperiosteally from the midline. A congenital defect in the posterior arch of C1 was noted. First, the left side C1 lateral mass screw was put after identifying the entry point. On the right side, the aberrant VA was freed from the posterior arch of C1 and retracted, inferiorly exposing the lateral mass of C1 along with facets of C1-C2 joint, and C1 lateral mass screw was inserted. Further, laminar screws were placed bilaterally in C2. C1 was reduced over C2 using rod cantilever mechanism and by applying compression force bilaterally between the C1 lateral mass and the C2 laminar screws. Decompression was achieved by removing the remaining C1 posterior arch and corticated bony fragment from the midline. Harvested local bone autograft was placed in the C1-C2 joint on the left side and the prepared fusion bed posteriorly (Figs. 4 and 5).

Postoperatively, because of poor respiratory effort, the patient was kept on ventilator support, and postoperative day 4, tracheostomy was done. The patient was then weaned to a T-piece at 1 week and was subsequently maintaining saturation on room air at 2 weeks.

Gait training was started, and post-operative neurological assessment showed normal tone in both upper and lower limbs at 6 weeks. At 6 months, the patient started walking with support and had complete recovery of bowel movements and partial recovery in bladder sensations. At final follow-up of 18 months, the patient is walking independently (Nurick Grade 2). The patient has returned to his routine daily activities with no motor deficit in bilateral upper and lower limbs (Fig. 6).

The atlantoaxial joint, located between the first and second cervical vertebrae, is a complex joint that allows for a significant range of motion in the neck [5]. Non-traumatic atlantoaxial subluxation can lead to pain, stiffness, deformity, and neurological deficits. The condition can be caused by a variety of factors, including congenital abnormalities, degenerative changes, and inflammatory conditions [6]. In congenital cases, atlantoaxial subluxation may be associated with a VA anomaly, which can further complicate the condition. Any disruption to its flow can lead to serious neurological consequences, including cerebrovascular injuries [7]. Embryonic development of VA can easily explain various variations found at the CVJ [8]. VA variation at the CVJ is of 3 types – persistent first intersegmental artery (FIA), extracranial origin of the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA), and fenestration of the VA [9,10]. The most common is persistent FIA, present in 3.2% of patients. The next is PICA, present in 1.1% of cases. The least common variant is fenestration, present in 0.9% of patients, which was present in the present case. It occurs when there is both a normal VA branch as well as a persistent FIA, which then merge within the spinal canal [11]. VA anomaly with congenital CVJ pathology is a rare but potentially disabling condition that requires prompt diagnosis, thorough evaluation of the abnormal anatomy, and treatment. Surgical management typically involves decompression of the spinal cord and reduction of the joint, and stabilization. There are several surgical techniques that may be used, including posterior fixation, anterior fixation, and combined approaches. The choice of surgical technique depends on various factors, including the location and severity of the subluxation, the presence of other spinal abnormalities, and the patient’s overall health status. Among posterior fixation methods between C1 and C2, C1 lateral mass–C2 pedicle screw fixation is more popular and rigid [12]. These variations in VA may affect screw placement to the C1 lateral mass. Wright et al. reported the incidence of VA injury in CVJ anomalies during screw placement to the rate of 4.1% [13]. Hong et al. have described various methods to minimize this injury by predetermining the entry point [14]. The first technique is to mobilize VA inferiorly together with C2 nerve root before screw placement at the C1 inferior lateral mass, used in the present case lateral mass screw insertion on the right side. Another technique is to use C1-2 trans-articular screw fixation, which could not be used because of the presence of subluxated C1/C2 joint and high riding VA. The third technique is skipping the C1 level and using C0 as the proximal fixation level, as Abtahi et al. did in their case [11]. To save the motion of the C0-C1 joint in the young, we preferred not to use this fixation method. The third method is to choose the superior lateral mass as an alternative starting point. But this required a persistent FIA in which there is complete absence of a VA remnant in the normal position superior to the C1 ring. The last technique they described was to choose the C1 dorsal arch as an entry point, but because of the deficient posterior arch, this technique also could not be used. As the C2 pedicles were very narrow in the sagittal plane and the spinous process height was adequate, translaminar screws were inserted, which have shown equal pull-out strength compared to C2 pedicle screws [15] along with decreased chances of VA injuries in VA anomalies [16]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first surgical case report addressing these complex bony and vertebral anomalies at the CVJ along with VA anomalies in a single patient, using the C1 lateral mass and C2 laminar screws. Blunt trauma to the neck with a congenital CVJ anomaly may have induced the patient’s symptoms. The ventral and dorsal bony pathology compressed the upper cervical spinal cord. It has been shown that decompression alone in these pathologies may lead to neurological deterioration [17]. Hence, posterior decompression for the spinal cord along with posterior fixation to reduce the atlantoaxial joint was performed in the case. While surgical management of congenital AAS with VA anomaly can be effective, it is not without risks. Complications may include infection, bleeding, nerve injury, and device failure. Pre-operative thorough evaluation and planning of these conditions are crucial for surgical planning. The usefulness of 3D CTA for evaluating VA anomalies at the CVJ has been described in various papers [2]. In addition, we must also pay great heed to subluxation between C1 and C2 in not only the horizontal direction, but also the vertical direction, because vertical dislocation is often missed [18]. The long-term outcomes of surgery for this condition are not well established in the literature, and this report might provide insight into fully understanding the risks and benefits of posterior decompression and C1-C2 screw rod construct even in cases with aberrant bony and VA anomalies.

Our case report demonstrates that a thorough clinical and imaging evaluation of the CVJ is of paramount importance for the diagnosis and surgical planning. This study adds to the limited body of literature on spinal enchondromas and underscores the importance of long-term follow-up in these patients. Early surgical intervention, coupled with regular monitoring, can effectively manage this rare condition and provide patients with a sustained, symptom-free life.

Thorough pre-operative evaluation and individualized surgical planning are crucial in managing congenital atlantoaxial subluxation with VA anomalies. Advanced imaging techniques identifying complex anatomical variations, meticulous surgical techniques tailored to the patient’s unique anatomy, can lead to successful neurological recovery and restoration of functionality.

References

- 1.Hong JT, Kim IS, Lee HJ, Park JH, Hur JW, Lee JB, et al. Evaluation and surgical planning for craniovertebral junction deformity. Neurospine 2020;17:554-67. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Yamazaki M, Koda M, Aramomi MA, Hashimoto M, Masaki Y, Okawa A. Anomalous vertebral artery at the extraosseous and intraosseous regions of the craniovertebral junction: Analysis by three-dimensional computed tomography angiography. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:2452-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Wakao N, Takeuchi M, Nishimura M, Riew KD, Kamiya M, Hirasawa A, et al. Vertebral artery variations and osseous anomaly at the C1-2 level diagnosed by 3D CT angiography in normal subjects. Neuroradiology 2014;56:843-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Nazemi AK, Bickley SR, Behrend CJ, Carmouche JJ. C1-2 Fixation approach for patients with vascular irregularities: A case report. Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil 2017;8:263-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Mercer SR, Bogduk N. Joints of the cervical vertebral column. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2001;31:174-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Gencpinar P, Erkan M. Non-traumatic atlanto-axial rotatory subluxation: A rare cause of neck stiffness. Turk J Emerg Med 2015;15:145-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Byun CW, Lee DH, Park S, Lee CS, Hwang CJ, Cho JH. The association between atlantoaxial instability and anomalies of vertebral artery and axis. Spine J 2022;22:249-55. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Padget DH. The Development of the Cranial Arteries in the Human Embryo. Vol. 32. United States: Carnegie Institution; 1948. p. 205-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Tokuda K, Miyasaka K, Abe H, Abe S, Takei H, Sugimoto S, et al. Anomalous atlantoaxial portions of vertebral and posterior inferior cerebellar arteries. Neuroradiology 1985;27:410-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Uchino A, Saito N, Watadani T, Okada Y, Kozawa E, Nishi N, et al. Vertebral artery variations at the C1-2 level diagnosed by magnetic resonance angiography. Neuroradiology 2012;54:19-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Abtahi AM, Darrel S, Lawrence BD. Vertebral artery anomalies at the craniovertebral junction: A case report and review of the literature. Evid Based Spine Care J 2014;5:121-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Goyal N, Bali S, Ahuja K, Chaudhary S, Barik S, Kandwal P. Posterior arthrodesis of atlantoaxial joint in congenital atlantoaxial instability under 5 years of age: A systematic review. J Pediatr Neurosci 2021;16:97-105. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Wright NM, Lauryssen C. Vertebral artery injury in C1-2 transarticular screw fixation: Results of a survey of the AANS/CNS section on disorders of the spine and peripheral nerves American association of neurological surgeons/congress of neurological surgeons. J Neurosurg 1998;88:634-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Hong JT, Jang WY, Kim IS, Yang SH, Sung JH, Son BC, et al. Posterior C1 stabilization using superior lateral mass as an entry point in a case with vertebral artery anomaly: Technical case report. Neurosurgery 2011;68:246-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Liu GY, Mao L, Xu RM, Ma WH. Biomechanical comparison of pedicle screws versus spinous process screws in C2 vertebra a cadaveric study. Indian J Orthop 2014;48:550-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Singh DK, Shankar D, Singh N, Singh RK, Chand VK. C2 Screw fixation techniques in atlantoaxial instability: A technical review. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 2022;13:368-77. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Wang S, Wang C, Yan M, Zhou H, Jiang L. Syringomyelia with irreducible atlantoaxial dislocation, basilar invagination and chiari I malformation. Eur Spine J 2010;19:361-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Umebayashi D, Hara M, Nakajima Y, Nishimura Y, Wakabayashi T. Posterior fixation for atlantoaxial subluxation in a case with complex anomaly of persistent first intersegmental artery and assimilation in the c1 vertebra. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo) 2013;53:882-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]