Tourniquet use in TKA is associated with a higher risk of nerve-related complications and avoiding tourniquet may lead to better clinical outcomes and early post-operative ROM.

Dr. Neil Ashwood, Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Queens Hospital Burton, United Kingdom DE13 0RQ. E-mail: neil.ashwood@nhs.net

Introduction: Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) often uses a tourniquet to enhance surgical visualization and reduce intraoperative blood loss. Despite its benefits, tourniquet use is associated with several complications such as skin blistering, nerve palsy, and deep vein thrombosis. The literature reveals a divided opinion on whether TKA should be performed with or without a tourniquet, with conflicting results on postoperative pain, blood loss, and functional outcomes..

Materials and Methods: This study included patients aged 65 to 90 years undergoing elective unilateral TKA for osteoarthritis. Exclusion criteria included patients with a Body mass index ≥35, rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, prior knee surgery, and on anticoagulation medication. The study focused on comparing the neurology through nerve conduction studies and functional outcomes of TKA performed with and without a tourniquet. Some key metrics included intraoperative blood loss, surgical duration, post-operative pain, analgesic use, and range of motion (ROM).

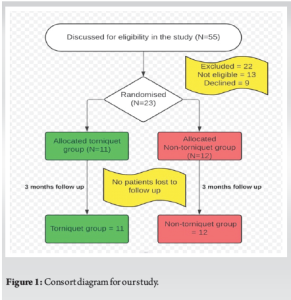

Results: The study recruited 55 patients aged ranging from 65 to 90 years who were randomized into two groups.22 patients were excluded, and the final analysis involved 23 patients. Tourniquet use resulted in lower blood loss (140 mL vs. 215 mL) and shorter operative times (87 min vs. 95 min) compared to the non-tourniquet group. However, the tourniquet group had higher incidences of nerve palsy in the immediate postoperative period as compared to the other group. Both the groups showed significant improvements in post-operative ROM, but the tourniquet group had higher post-operative pain and analgesic requirements, and this was statistically significant.

Conclusion: Tourniquet use in TKA reduces intraoperative blood loss and operative time but is associated with a higher risk of nerve-related complications and increased post-operative pain. The findings suggest that avoiding tourniquet use may lead to better overall clinical outcomes and early post-operative ROM.

Keywords: Tourniquets, total knee replacement, arthroplasty, nerve conduction study, nerve injury.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA), a frequently employed surgical procedure, commonly integrates the utilization of a tourniquet. According to a recent survey, 95% of the members comprising the American Association of Hip and Knee Surgeons incorporate a tourniquet during TKA [1]. The prevailing consensus among orthopedic surgeons is grounded in the belief that extensive soft tissue release and bone cuts may contribute to augmented blood loss in TKA. Conversely, the application of a tourniquet has been posited to confer superior visualization of anatomical structures, concurrently mitigating intraoperative blood loss. This ostensibly enhances the quality of cementation and facilitates other surgical maneuvers [2]. In addition, the deployment of a tourniquet is purported to reduce overall operation time. Hernandez et al. observed a significantly abbreviated duration of TKA procedures when a tourniquet was employed [3].

A corpus of literature underscores potential complications linked to the use of a tourniquet in TKA. These complications encompass skin blistering, wound hematoma, wound ooze, muscle injury, rhabdomyolysis, nerve palsy, post-operative stiffness, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism (PE) [3-10]. Furthermore, these complications have the propensity to impede post-operative functional recovery and subject patients to unnecessary discomfort. Reports of severe and fatal complications following TKA with a tourniquet have been documented, including pulmonary edema [11], renal failure [10], and PE leading to fatalities in certain instances.

Numerous randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses have endeavored to shed light on the adverse consequences associated with tourniquet use in TKA. However, a lingering discord prevails within the academic discourse regarding the optimal approach to TKA surgery, as to whether it should be conducted with or without the deployment of a tourniquet. This discord is evidenced by the conflicting perspectives articulated by various researchers: Smith and Hing found that tourniquet use can lead to increased post-operative pain [12], Tai et al. highlighted the potential for reduced blood loss but also noted the risk of nerve damage [2], and Smith et al. observed no significant difference in functional outcomes between surgeries performed with and without a tourniquet [12].

This was a randomized double-blinded prospective trial comparing two groups of patients with and without tourniquet use during total knee replacements in a District General Hospital in United Kingdom after Ethics Committee clearance (BEC 145).

Overall study design and duration

Fifty-five consecutive patients scheduled for total knee replacement were recruited (Fig. 1). Patients were randomly allocated to one limb of the trial by opening a sealed envelope just before surgery in the anesthetic room. The patient had standardized anesthetic and total knee replacement surgery as per the protocol. Pre-operative details including hemoglobin (Hb), range of motion (ROM), intraoperative details including blood loss, duration of surgery, and post-operative outcomes were recorded by one of the junior doctors who was not present during the surgery.

Post-operative nerve conduction studies were performed by a neurophysiologist at 6 weeks, who was blinded to the patient’s details about the surgery. A meticulous record was maintained concerning intraoperative blood loss, surgical duration, the quality of surgical visibility and difficulties encountered, post-operative pain levels, analgesic consumption patterns, and any necessitated transfusions.

Inclusion criteria

Individuals aged 65–90 years scheduled for elective unilateral TKA due to gonarthrosis, classified within stages 3–5 according to Ahlbäck, were considered for inclusion [14]. In addition, patients had to be free of severe concomitant ailments and classified under the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) categories 1 or 2.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with coagulopathies/on antiplatelets treatment, sickle cell disease or hemoglobinopathies, peripheral vascular disease, a history of prior knee surgery, or rheumatoid arthritis were excluded from this study. Noteworthy to mention is the exclusion of individuals with a body mass index (BMI) equal to or exceeding 35, thereby precluding their participation.

Data collection

Data collection focused on assessing the impact of tourniquet use on both functional and clinical outcomes in TKA. Parameters recorded included intraoperative blood loss, surgical duration, quality of surgical visibility, encountered difficulties, post-operative pain levels, analgesic consumption patterns, and any necessitated transfusions. The influence on knee ROM was also meticulously documented.

Statistical tests

Statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Package for the social Sciences ( version 24 (IBM Statistics, Chicago, IL). The one-sample Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was employed to assess data distribution, and the Mann–Whitney U-test was utilized to compare parameters between the tourniquet and non-tourniquet groups. Chi-square tests were used for non-parametric data.

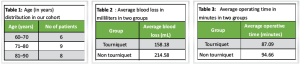

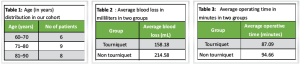

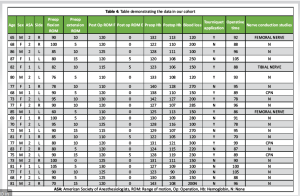

The analysis evaluates the outcomes of total knee replacement surgeries in 23 patients, comparing those with and without tourniquet application. The patient cohort ranged from 65 to 90 years old (Table 1), with an even distribution of 11 males and 12 females, all classified with ASA Classification scores, with 13 patients were ASA II and 10 were ASA I.

Pre-operative ROM in flexion varied from 60° to 105°, and in extension from 0° to 15°. Post-operative improvements were notable, with ROM flexion reaching 110°–130° and most patients achieving full extension.

Haemoglobin (Hb) levels showed a mean pre-operative value of 128 g/L, dropping to 112 g/L post-operatively. Blood loss was significantly lower in the tourniquet group, averaging 158.18 mL (120–300 mL), compared to 214.58 mL (100–285 mL) in the non-tourniquet group (Table 2) and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001).

The average operative time was 87 min for the tourniquet group, which also had a notable incidence of nerve palsy: Two cases of femoral nerve palsy, one of tibial nerve palsy, and three of common peroneal nerve palsy (Table 3). Conversely, the non-tourniquet group, with an average operative time of 95 min, exhibited higher blood loss but no nerve palsy cases (Table 4).This difference is operative times between the two groups were statstiscally insignificant(P > 0.05); however, the incidence of post-operative nerve palsy in more than half of patients in whom tourniquet was used was stastically significant (P < 0.005).

Flexion and extension improvements were particularly significant in patients with pre-operative flexion <85° and extension deficits. While tourniquet use effectively reduced intraoperative blood loss and potentially shortened operative time, it increased the risk of post-operative nerve complications. Overall, both groups showed significant post-operative ROM improvements, indicating successful surgical outcomes in restoring joint function, and the differences were statistically insignificant (P > 0.05). These findings highlight the need to balance the benefits of reduced blood loss and shorter operative times against the risks of nerve-related complications when considering tourniquet use in total knee replacements

A salient discovery emanating from this investigation underscores the propensity of TKA with a tourniquet to accentuate post-operative complications. The employment of a tourniquet fails to ameliorate the cumulative blood loss, not withstanding its efficacy in mitigating intraoperative hemorrhage.

The ischemic ramifications and limb alterations induced by tourniquet application remain inadequately expounded upon. Ostman et al. delineated the ischemic transformations in skeletal musculature during arthroscopic ligament reconstruction, a context where surgical trauma is comparably less severe than in TKA [13]. Contrarily, Tsarouhas et al. delved into tourniquet-induced soft tissue damage during arthroscopic meniscectomy, appraising serum creatine phosphokinase levels in patients aged ≤ 40 years [15]. Their findings affirmed the safety of tourniquet use for durations under 30 minutes, with no discernible systemic responses. However, in our investigation, the tourniquet-administered group exhibited heightened pain levels and a concomitantly elevated requirement for analgesics, ostensibly attributable to the localized ischemic conditions engendered by the tourniquet, exacerbated by prolonged surgical durations compared to arthroscopic procedures.

Smith and Hing posit that tourniquet application effectively curtails intraoperative bleeding, yet fails to confer commensurate advantages in terms of post-operative bleeding, total blood loss, or transfusion rates [12]. Our findings align with a reduction in intraoperative bleeding with tourniquet use; however, the absence of clinical significance is evident, as not a single patient necessitated transfusion. In consonance with the conclusions of Tetro and Rudan and meta-analyses by Smith and Hing, and Tai et al., the assertion that tourniquet use ineffectively diminishes overall blood loss volume gains prominence [2,12,16].

Olivecrona et al. elucidate a consequential association between tourniquet time, cuff pressure, and an augmented risk of complications subsequent to TKA [8]. The utilization of a tourniquet emerges as a discernible risk factor for complications, attributed to the direct pressure of the tourniquet inflicting damage upon nerves and local soft tissues. In our cohort, the use of a tourniquet was associated with the development of nerve palsy in over 50% of cases. This complication was confirmed by nerve conduction studies performed within six weeks following the index surgery, highlighting a significant correlation between tourniquet application and postoperative neurological impairment. Moreover, the release of the tourniquet induces reactive hyperemia and heightened fibrinolytic activity, escalating tissue pressure and local inflammation, precipitating tissue hypoxia and, consequently, compromising wound healing. The imposition of a tourniquet further restrains the quadriceps mechanism, thereby altering intraoperative patellofemoral tracking.

This study has several limitations that need to be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size of 23 patients limits the generalizability of the findings and reduces the statistical power of the study. The study’s exclusion criteria, such as the elimination of individuals with a BMI equal to or exceeding 35, those with rheumatoid arthritis, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes, a history of prior knee surgery, or those on anticoagulation medication, may limit the applicability of the results to the broader population of TKA patients. The study also did not account for variations in surgical technique and post-operative care, which could influence the outcomes. The assessment of functional and clinical outcomes, including pain levels, ROM, and complications, relied on self-reported measures and clinical observations, which could introduce subjective bias. The follow-up period may not have been sufficient to capture long-term complications and outcomes associated with tourniquet use.

The current investigation offers empirical substantiation for the hypothesis that refraining from the use of tourniquets in the context of TKA results in more favorable clinical outcomes, particularly with regard to the incidence of post-operative complications and the early ROM. Although the employment of tourniquets during surgery can effectively diminish intraoperative blood loss and reduce the duration of the surgical procedure, the potential for nerve damage presents a significant risk that must be carefully considered in evaluating these benefits. Consequently, there is a pressing need for additional research encompassing larger and more heterogeneous patient cohorts to thoroughly elucidate the long-term outcomes and to refine surgical methodologies for TKA, thereby enhancing overall patient care and surgical efficacy.

Tourniquet use in TKA is associated with a higher risk of nerve-related complications, and avoiding tourniquet may lead to better clinical outcomes and early post-operative ROM.

References

- 1.1. Berry DJ, Bozic KJ. Current practice patterns in primary hip and knee arthroplasty among members of the American association of hip and knee surgeons. J Arthroplasty 2010;25(Suppl 6):2-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.2. Tai TW, Lin CJ, Jou IM, Chang CW, Lai KA, Yang CY. Tourniquet use in total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:1121-30. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.3. Hernandez AJ, Almeida AM, Favaro E, Sguizzato GT. The influence of tourniquet use and operative time on the incidence of deep vein thrombosis in total knee arthroplasty. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 2012;67:1053-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.4. Burg A, Dudkiewicz I, Heller S, Salai M, Velkes S. The effects of using a tourniquet in total knee arthroplasty: A study of 77 patients. J Musculoskelet Res 2009;12:137-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.5. Palmer SH, Graham G. Tourniquet-induced rhabdomyolysis after total knee replacement. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1994;76:416-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.6. O’Leary AM, Veall G, Butler P, Anderson GH. Acute pulmonary oedema after tourniquet release. Can J Anaesth 1990;37:826-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.7. Olivecrona C, Lapidus LJ, Benson L, Blomfeldt R. Tourniquet time affects postoperative complications after knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2013;37:827-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.8. Olivecrona C, Ponzer S, Hamberg P, Blomfeldt R. Lower tourniquet cuff pressure reduces postoperative wound complications after total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled study of 164 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012;94:2216-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.9. Olivecrona C, Tidermark J, Hamberg P, Ponzer S, Cederfjall C. Skin protection underneath the pneumatic tourniquet during total knee arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial of 92 patients. Acta Orthop 2006;77:519-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.10. Carroll K, Dowsey M, Choong P, Peel T. Risk factors for superficial wound complications in hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Microbiol Infect 2014;20:130-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.11. Clarke MT, Longstaff L, Edwards D, Rushton N. Tourniquet-induced wound hypoxia after total knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:40-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.12. Smith TO, Hing CB. Is a tourniquet beneficial in total knee replacement surgery? A meta-analysis and systematic review. Knee 2010;17:141-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.13. Ostman B, Michaelsson K, Rahme H, Hillered L. Tourniquet-induced ischemia and reperfusion in human skeletal muscle. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2004;418:260-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.14. Ahlbäck S. Osteoarthrosis of the knee. A radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Diagn (Stockh) 1968;2:7-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.15. Tsarouhas A, Hantes ME, Tsougias G, Dailiana Z, Malizos KN. Tourniquet use does not affect rehabilitation, return to activities, and muscle damage after arthroscopic meniscectomy: A prospective randomized clinical study. Arthroscopy 2012;28:1812-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.16. Tetro AM, Rudan JF. The effects of a pneumatic tourniquet on blood loss in total knee arthroplasty. Can J Surg 2001;44:33-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]