Solitary osteolytic lesions in young children can mimic malignant neoplasms but may represent benign conditions such as Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Biopsy with immunohistochemistry is essential for diagnosis, and curettage with intralesional steroids can lead to complete resolution with minimal recurrence.

Dr. Piyush Sureka, Department of Orthopaedics, Star Hospitals, Survey No.74, Financial District, Nanakramguda, Hyderabad, Telangana - 500008, India. E-mail: dr.piyush.sureka@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteolytic lesions in the long bones of the upper and lower limbs in early childhood can arise from various conditions, ranging from benign cysts to malignancies. While malignant neoplasms are often suspected, benign conditions like Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) can present similarly. We report a rare case of an 11-month-old girl with a solitary osteolytic lesion in the distal radius, which was diagnosed as LCH. The unusual combination of age, location, and presentation provides new insights into the management of LCH in infants.

Case Report: An 11-month-old girl presented with a 5-day history of pain and bony swelling in the right forearm, with no history of trauma or fever. Examination revealed localized swelling and tenderness over the distal radius, with normal skin and joint mobility. Inflammatory markers were mildly elevated. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging revealed an expansile lytic lesion of the distal radius. Biopsy showed histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and eosinophils, with Immunohistochemistry (S100+, CD1a+, Langerin+, CD68+) confirming LCH. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography revealed no systemic involvement. Curettage followed by an intralesional injection of methylprednisolone (40 mg/mL) was performed. At 2-year follow-up, radiographs showed no recurrence, with excellent healing.

Conclusion: LCH is a rare cause of solitary osteolytic lesions in children. Curettage with intralesional steroids can achieve complete resolution with minimal recurrence.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, eosinophilic granuloma, distal radius, osteolytic lesion, benign tumor, bone tumors in infancy.

An osteolytic lesion in the long bones of the upper limb, especially in early childhood, may be caused by a wide variety of conditions. These lesions are often considered to be manifestations of malignant neoplasms. The etiological spectrum ranges from benign causes such as simple bone cysts to malignant tumours [1]. It is essential to note that certain benign and inflammatory conditions may also present as an osteolytic lesion. One such condition is Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH), also known as eosinophilic granuloma (EG), which usually manifests as solitary or multiple osteolytic lesions in older children or adolescents [2]. We present the case report and discuss the management of a solitary osteolytic lesion in the distal radius of an 11-month-old girl, which was diagnosed as LCH. This case is noteworthy due to the rare combination of age, anatomical location, and clinical presentation, which collectively provide new insights into the spectrum of LCH in infants.

An 11-month-old girl was brought by her parents to our hospital with a complaint of pain and bony swelling in the right forearm for 5 days. There was no history of injury or fever. The pain was insidious in onset. On examination, there was bony swelling and tenderness over the distal one-third of the right forearm with no local rise of temperature. There were no scars or sinuses. The skin over the forearm was normal (Fig. 1). Passive movements in the wrist, elbow, and forearm were normal.

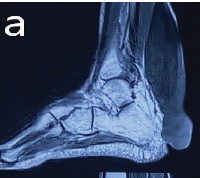

We evaluated the patient through comprehensive blood investigations and radiological imaging modalities. The white blood cell count was 13,000 cells/mm3. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 28 mm/h and C-reactive protein levels were <5 mg/L. A radiograph of the right forearm revealed an expansile lytic lesion with septations in the distal one-third of the radius extending from the metaphysis to the diaphysis with a narrow zone of transition and clear boundaries (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the forearm showed an ill-defined altered signal, hyperintense on the proton density fat-saturated sequence and hypointense in T1 involving the metadiaphyseal region of the distal radius for a length of 5 cm (Fig. 3a).

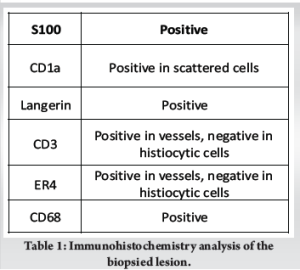

Intramedullary heterogeneously hyperintense area was noted in the medulla causing expansion, cortical destruction at the volar-ulnar aspect of radius with adjacent soft tissue measuring 1.5 × 1.2 cm. The common interosseous artery was noted to be traversing medial to the soft tissue component. Periosteal elevation was seen with subperiosteal hyperintense signal. Whole body positron emitted tomography-computed tomography (Positron emission tomography [PET]-computed tomography [CT]) scan showed a metabolically active, ill-defined permeative, aggressive, expansile/punched out lytic lesion with a soft tissue component involving the metadiaphysis of distal end of right radius (Fig. 3b). No other fluorodeoxyglucose avid lesions were visualised in the rest of the body. We did an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the lesion. Gram staining and acid-fast staining of the tissue samples revealed no micro-organisms. Aerobic culture of the sample revealed no bacterial growth after 48 h of incubation. Histopathological examination showed diffuse infiltration of histiocytes, admixed with multinucleated giant cells and eosinophils. The histiocytes had round to oval vesicular nuclei, indistinct nucleoli, and moderate to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Prominent nuclear grooves were not seen. Intervening stromal thin-walled blood vessels were noted (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) markers were positive for several markers, which are detailed in Table 1. These features were consistent with LCH (Fig. 4).

Intramedullary heterogeneously hyperintense area was noted in the medulla causing expansion, cortical destruction at the volar-ulnar aspect of radius with adjacent soft tissue measuring 1.5 × 1.2 cm. The common interosseous artery was noted to be traversing medial to the soft tissue component. Periosteal elevation was seen with subperiosteal hyperintense signal. Whole body positron emitted tomography-computed tomography (Positron emission tomography [PET]-computed tomography [CT]) scan showed a metabolically active, ill-defined permeative, aggressive, expansile/punched out lytic lesion with a soft tissue component involving the metadiaphysis of distal end of right radius (Fig. 3b). No other fluorodeoxyglucose avid lesions were visualised in the rest of the body. We did an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the lesion. Gram staining and acid-fast staining of the tissue samples revealed no micro-organisms. Aerobic culture of the sample revealed no bacterial growth after 48 h of incubation. Histopathological examination showed diffuse infiltration of histiocytes, admixed with multinucleated giant cells and eosinophils. The histiocytes had round to oval vesicular nuclei, indistinct nucleoli, and moderate to abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm. Prominent nuclear grooves were not seen. Intervening stromal thin-walled blood vessels were noted (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) markers were positive for several markers, which are detailed in Table 1. These features were consistent with LCH (Fig. 4).

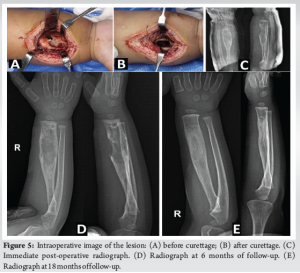

The diagnosis was confirmed as LCH based on histopathological and IHC analysis. The diagnostic imaging and biopsy were done over a span of 4 weeks. The lesion’s radiographic appearance evolved rapidly over this period, raising concern (Fig. 2). After pre-anaesthetic evaluation, curettage and intralesional steroid injection was planned under general anaesthesia. The extent of the lesion was marked using C-arm fluoroscopy. A skin incision was made on the volar aspect of the right forearm. The lesion was exposed through the modified Henry’s approach (Fig. 5a). Intra-lesional curettage was done. After curettage (Fig. 5b), 1 mL of methylprednisolone acetate (40 mg/mL) was injected into the lesion. After surgery, the right upper limb was splinted (Fig. 5c) in an above-elbow Plaster of Paris back slab to prevent a pathological fracture.

The back slab was removed after 3 weeks, and range of motion was allowed at the elbow and wrist joints. The patient was followed up at regular intervals for 2 years. Radiographs were obtained at every follow-up (Fig. 5c and d). There were no complications such as pathological fracture, neurovascular deficits, and growth arrest of the affected bone. There were no signs of recurrence at 2 years, and the curetted lesion showed good healing and excellent remodelling (Fig. 5e).

LCH is a rare lesion that is characterised by the presence of Langerhans cells, histiocytes with distinctive racquet-shaped Birbeck granules that are visible under electron microscopy. LCH is a part of a wide spectrum of disorders referred to as Histiocytosis X, which comprises syndromes such as Hand–Schüller–Christian disease and Letterer–Siwe disease. Solitary LCH constitutes up to 80% of histiocytosis X lesions in children, with nearly 90% of cases occurring in pediatric populations [3]. While the exact pathogenesis remains unclear, infectious, immune, and neoplastic causes have been proposed [3]. The most frequently affected bones are the skull (34%), spine (15%), ribs (7%), and long bones (15%), with the diaphysis being the most commonly involved region in long bones (58%), followed by the metaphysis [4]. The clinical presentation is heterogeneous and non-specific, encompassing symptoms such as pain and localized swelling, as well as incidental detection during imaging conducted for unrelated conditions or trauma. In certain cases, pathological fractures may be observed. Physical examination typically reveals no significant findings, and laboratory investigations are generally non-specific, though a mild elevation in erythrocyte sedimentation rate may occasionally be noted. Radiographically, acute lesions are typically seen in the metaphysis or diaphysis characterized by aggressive, lytic, medullary-based patterns with poorly defined margins, making differentiation from infection or Ewing’s sarcoma challenging [5]. Over time, these lesions may develop more distinct features, including sclerotic scalloping, cortical erosion or thickening, widening of the medullary cavity, periosteal reactions (such as “onion peel” appearance), and potential soft tissue involvement [5]. In our patient, the lesion grew at an alarming rate in a span of just 4 weeks (Fig. 2), prompting a thorough evaluation and prompt surgical intervention. It is crucial to differentiate LCH from conditions such as osteomyelitis and Ewing’s sarcoma, as the management strategies and prognostic outcomes for these conditions differ significantly, with substantial implications for the patient’s treatment and overall prognosis. Imaging modalities such as CT and MRI are particularly useful in evaluating soft tissue extension, with MRI being highly sensitive for detecting bone marrow changes and associated soft tissue masses, although the findings are often non-specific [3]. Bone scintigraphy, however, is of limited utility, detecting only 35% of lesions [6]. Definitive diagnosis relies on biopsy, with confirmation achieved through immunohistochemical markers, such as S100, CD1, and OKT6, or electron microscopy. A solitary bone lesion rarely progresses to involve multiple bones or visceral organs. However, patients presenting with a single lesion should undergo comprehensive evaluation to exclude the presence of additional lesions. PET scans are highly sensitive for identifying LCH lesions and assessing therapeutic response, but are costly, involve significant radiation exposure, and have limited availability. It is not recommended to change the method of evaluation (radiographs), as it may lead to discrepancy in future assessments [7]. Following the ALARA principle (as low as reasonably achievable), follow-up imaging should focus on the initially affected region to minimize radiation exposure. Treatment approaches for solitary EG vary. While spontaneous remission is possible, observation or biopsy alone to confirm the diagnosis has been suggested as a treatment approach. A study of six skeletally immature patients reported spontaneous resolution without recurrence after biopsy (three open and three percutaneous), indicating that surgery might have a higher recurrence risk than less invasive methods [8]. Conservative treatment for EG can be unpredictable and may lead to significant morbidity, including pain, restricted activity, growth disturbances, or pathological fractures [9]. Chemotherapy is generally not recommended for solitary lesions and should be reserved for systemic disease or solitary lesions in high-risk, non-resectable locations [9,10]. Radiotherapy is rarely utilized due to the risk of inducing latent neoplasms [11]. Systemic therapies, such as chemotherapy and corticosteroids, are generally reserved for cases of multisystem disease and are avoided in solitary lesions due to their toxicity and unpredictable efficacy [12]. Symptomatic and surgically accessible lesions are typically treated with biopsy, curettage, and bone grafting, if necessary [13]. Local corticosteroid injections have demonstrated favorable outcomes, including pain resolution and lesion healing within 2 months [14]. The mechanism of intralesional corticosteroids remains unclear. A study of 39 patients with solitary EG found that percutaneous needle biopsy and intralesional methylprednisolone effectively relieved pain, avoided surgery, and achieved osseous healing in 97% of cases [15]. Chadha et al. reported a similar lesion in the radius of an 11-year-old patient, which was treated with curettage. At 2 years of follow-up, there was complete resolution of the lesion with remodelling of the cortex [16]. A bony lesion that usually presents with pain, without soft-tissue involvement, is the most common presentation and has the best prognosis. Other favorable prognostic factors include age >2 years and the lack of pulmonary, hepatic, hematopoietic lesions, or multiple bone involvement [4].

LCH is a rare cause of solitary lytic lesion in children. The radiological and clinical findings may often be vague. The gold standard for diagnosis is biopsy. Management with curettage and intralesional methylprednisolone injection can lead to complete resolution of the lesion with minimal chance of recurrence. Success in diagnosis hinges on a high degree of suspicion.

A high degree of suspicion is required for early diagnosis of Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis. Differentiation from conditions such as osteomyelitis and Ewing’s sarcoma is crucial and has far-reaching implications on the management and prognosis of the patient.

References

- 1.Subramanian S, Viswanathan VK. Lytic bone lesions. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Khung S, Budzik JF, Amzallag-Bellenger E, Lambilliote A, Ares GS, Cotten A, et al. Skeletal involvement in Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Insights Imaging 2013;4:569-79. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Azouz EM, Saigal G, Rodriguez MM, Podda A. Langerhans’ cell histiocytosis: Pathology, imaging and treatment of skeletal involvement. Pediatr Radiol 2005;35:103-15. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Bollini G, Jouve JL, Gentet JC, Jacquemier M, Bouyala JM. Bone lesions in histiocytosis X. J Pediatr Orthop 1991;11:469-77. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.McCullough CJ. Eosinophilic granuloma of bone. Acta Orthop Scand 1980;51:389-98. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Parker BR, Pinckney L, Etcubanas E. Relative efficacy of radiographic and radionuclide bone surveys in the detection of the skeletal lesions of histiocytosis X. Radiology 1980;134:377-80. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Haupt R, Minkov M, Astigarraga I, Schäfer E, Nanduri V, Jubran R, et al. Langerhans Cell Histiocytosis (LCH): Guidelines for diagnosis, clinical work-up, and treatment for patients till the age of 18 Years. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:175-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Plasschaert F, Craig C, Bell R, Cole WG, Wunder JS, Alman BA. Eosinophilic granuloma. A different behaviour in children than in adults. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:870-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Angelini A, Mavrogenis AF, Rimondi E, Rossi G, Ruggieri P. Current concepts for the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic granuloma of bone. J Orthop Traumatol 2017;18:83-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Levy EI, Scarrow A, Hamilton RC, Wollman MR, Fitz C, Pollack IF. Medical management of eosinophilic granuloma of the cervical spine. Pediatr Neurosurg 1999;31:159-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Egeler RM, Neglia JP, Puccetti DM, Brennan CA, Nesbit ME. Association of langerhans cell histiocytosis with malignant neoplasms. Cancer 1993;71:865-73. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.De Camargo OP, De Oliveira NR, Andrade JS, Filho RC, Croci AT, Filho TE. Eosinophilic granuloma of the ischium: Long-term evaluation of a patient treated with steroids. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1992;74:445-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Sessa S, Sommelet D, Lascombes P, Prévot J. Treatment of langerhans-cell histiocytosis in children. Experience at the children’s hospital of nancy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:1513-25. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Mavrogenis AF, Abati CN, Bosco G, Ruggieri P. Intralesional methylprednisolone for painful solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the appendicular skeleton in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2012;32:416-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Yasko AW, Fanning CV, Ayala AG, Carrasco CH, Murray JA. Percutaneous techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of localized langerhans-cell histiocytosis (Eosinophilic Granuloma of Bonee). J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80:219-28. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Chadha M, Agarwal A, Agarwal N, Singh MK. Solitary eosinophilic granuloma of the radius. An unusual differential diagnosis. Acta Orthop Belg 2007;73:413-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]