Vulvar pressure sore is an avoidable complication of Thomas splint, it can be avoided by using a proper size of Thomas splint with adequate padding . These complications can result in increase in morbidity and hospital stay of patient specifically in patient having haematological conditions such as sickle cell disease.

Dr. Rakesh Dhaka, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Raipur, Chhatisgarh, India. E-mail: dhakarakesh341@gmail.com

Introduction: Pressure ulcers are common complications in immobilized patients, typically occurring over bony prominences. However, in rare instances, particularly in high-risk individuals with hematologic disorders such as sickle cell disease, ulcers may develop at unusual anatomical sites due to external medical devices. This case highlights a rare presentation of a vulvar pressure ulcer caused by prolonged application of a Thomas splint in a patient with homozygous sickle cell disease (HbSS).

Case Report: A 24-year-old woman with HbSS was admitted with a closed distal femoral shaft fracture. She was immobilized using a Thomas splint. On the 15th day of hospitalization, she developed a necrotic ulcer over the labia majora, diagnosed as a vulvar pressure ulcer secondary to device compression. Conservative wound management was initiated, followed by surgical debridement and closure using local advancement flaps. Orthopedic care was modified, and internal fixation of the fracture was later performed in a pressure-avoiding position. The wound healed completely within 2 weeks of surgery.

Conclusion: Vulvar pressure ulcers are rare and often underdiagnosed, particularly in patients with risk factors like sickle cell disease. This case emphasizes the need for regular inspection of pressure points, patient education, and multidisciplinary collaboration to prevent and manage such complications. Thoughtful application and monitoring of immobilization devices can reduce the risk of pressure injuries in vulnerable populations.

Keywords: Pressure ulcer, sickle cell disease, vulvar wound, Thomas splint, orthopedic complication.

Pressure ulcers, also known as pressure injuries or decubitus ulcers, are areas of localized tissue damage that occur as a result of sustained pressure, often compounded by shear forces, affecting the skin and the underlying structures. They most commonly develop over bony prominences such as the sacrum, heels, or ischial tuberosities, but can occasionally occur in atypical locations, particularly when external medical devices or prolonged immobilization are involved [1,2]. One such rare and under-reported site is the vulva, where pressure ulcers are seldom documented in the literature [3,4]. The Thomas splint, introduced during World War I, remains a widely used orthopedic device for stabilizing femoral fractures, particularly in trauma settings and resource-limited environments. Despite its efficacy, improper application or prolonged use may lead to pressure-related complications. While pressure injuries typically occur at skeletal pressure points, rare instances of soft-tissue necrosis involving the genitalia have also been observed, though they are infrequently reported [2,5]. Patients with homozygous sickle cell disease (HbSS) present additional risk factors for pressure ulcer development. The pathophysiology of sickle cell disease–including chronic hemolysis, recurrent vaso-occlusion, and impaired microcirculation–significantly impairs wound healing and lowers the threshold for ischemic tissue injury [6-8]. In such patients, even modest, unrelieved pressure from medical devices–particularly in sensitive anatomical regions such as the groin–can result in severe ulceration. We present a rare case of a vulvar pressure ulcer caused by prolonged compression from a Thomas splint in a young woman with HbSS. This report underscores the importance of vigilant skin assessment, especially in high-risk patients, and raises awareness about an unusual but preventable complication. Effective management requires a multidisciplinary approach that integrates wound care, surgical treatment, and ongoing orthopedic evaluation. Through this case, we aim to contribute to the limited literature on genital pressure ulcers and emphasize the need for cautious splint application and monitoring in vulnerable populations.

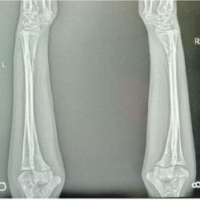

A 24-year-old woman with a known diagnosis of HbSS presented to the emergency department after sustaining a fall while descending stairs. She complained of acute left thigh pain and inability to bear weight. On physical examination, the left thigh demonstrated abnormal mobility consistent with a fracture, though the overlying skin was intact and there were no open wounds or neurovascular deficits. Radiographs (Fig. 1) confirmed a closed, isolated distal-shaft fracture of the left femur. A Thomas splint was applied for temporary immobilization in the emergency department. Given her underlying sickle cell disease and the development of an acute pain crisis, the patient was admitted to the critical care unit for multidisciplinary optimization before definitive surgical management.

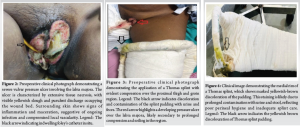

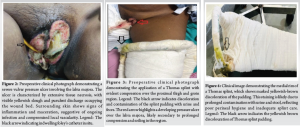

On the 15th day of hospitalization, the patient reported perineal swelling and discomfort that had been present for the preceding 4–5 days. She had previously concealed her symptoms due to fear and embarrassment, and hence, her external genitalia had not been examined earlier. On inspection, a large necrotic ulcer measuring 8 × 4 cm was identified over the left labia majora and extending to the right labia majora with surrounding erythema, induration, and foul-smelling discharge (Fig. 2).

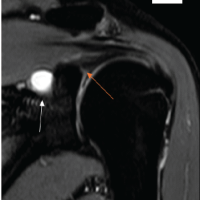

Microbiological cultures of the wound showed no bacterial growth. Histopathological examination of a skin biopsy from the ulcer margin revealed nonspecific acute inflammatory infiltrates with no evidence of vasculitis or granulomatous disease. Additional mucosal sites, including the oral mucosa and other perineal structures, were intact, ruling out systemic dermatologic or autoimmune conditions. Inspection of the Thomas splint revealed excessive proximal compression of the upper thigh and groin region (Fig. 3), likely contributing to continuous pressure over the vulvar region. A diagnosis of labial pressure sore secondary to Thomas splint compression (Fig. 4) was made.

Initial wound management involved removing the Thomas splint immediately and transferring the patient to a pressure-relieving mattress. The above-knee posterior slab with good padding was applied. Moist wound care was initiated using hydrogel and soft silicone dressings to promote autolytic debridement. Gauze padding was placed to separate the labia majora, prevent contamination from urine or stool, and offload pressure from the wound. Dressing changes were performed regularly. Repeated bedside debridement of necrotic tissue was performed, leading to a gradual reduction in slough and early signs of epithelialization at the wound edges (Fig. 5).

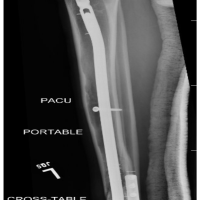

Despite improvement, the wound was deemed unlikely to heal completely with conservative management alone due to the extent of tissue loss and her underlying sickle pathology. Before the patient was taken to the operating theatre, a computed tomography urography was performed to rule out the presence of any fistula. She then underwent surgical debridement followed by secondary wound closure using local advancement flaps under spinal anesthesia (Fig. 6). Hematology support was provided throughout to minimize perioperative sickling risk. Meanwhile, for definitive fracture management, the Thomas splint was replaced with a well-padded above-knee posterior slab. After optimization, she underwent closed reduction and internal fixation of the distal femur fracture using an intramedullary femoral nail in the lateral decubitus position to avoid pressure on the healing vulvar wound (Fig. 7).

The patient tolerated all procedures well. The surgical site over the labia majora healed completely within 14 days post-closure, with no signs of infection or wound breakdown. She was discharged before complete suture removal with instructions for perineal care, positioning, and follow-up dressing. At follow-up, the surgical wound was completely healed, and the patient demonstrated independent knee movement while continuing with physiotherapy rehabilitation.

The vulvar wound demonstrated complete healing within 14 days following surgical closure, with no evidence of wound dehiscence, infection, or tissue necrosis. The femoral fracture fixation remained stable, and the patient maintained hemodynamic stability throughout her hospitalization. She was discharged before suture removal with comprehensive instructions regarding perineal hygiene, pressure offloading, and wound dressing care. At the 8-week post-operative follow-up, the surgical site remained fully healed with no signs of recurrence or infection. The patient was independently mobilizing the knee with the assistance of physiotherapy and showed satisfactory progression in fracture union.

Pressure ulcers are a major concern in acute and long-term care, typically affecting bony prominences such as the sacrum, ischium, and heels. However, vulvar pressure ulcers are rare and often misdiagnosed due to their unusual location and sensitive anatomy. This case highlights the multifactorial causes, diagnostic challenges, and management complexities of vulvar pressure sores. The National Pressure Ulcer Long-Term Care Study emphasized that outcomes depend not only on ulcer location but also on comorbidities and care settings, underscoring early detection and tailored interventions for all pressure ulcers, including rare ones like vulvar ulcers [1]. Pressure ulcers result from sustained pressure exceeding capillary closing pressure, causing ischemia and tissue death [2]. Although vulvar tissue is usually resilient, prolonged compression from devices such as improperly padded Thomas splints can cause injury, especially when compounded by systemic factors. Previous reports by Conde Montero et al. and Rakic et al. have documented vulvar pressure ulcers, noting frequent diagnostic delays due to misidentification as infections or dermatologic conditions and patient reluctance to report symptoms [3,4]. Our case further implicates orthopedic devices as a risk factor. Similarly, Rathore et al. described unusual pressure ulcers in spinal cord injury patients due to immobility and sensory deficits [5]. Although our patient lacked spinal pathology, immobilization and low pain perception during a sickle cell crisis created comparable vulnerability. Sickle cell disease complicates healing through chronic hemolysis, endothelial dysfunction, and vaso-occlusion, impairing microvascular flow and tissue repair [6,7]. Taylor et al. noted that even patients with fewer pain crises may suffer severe vascular damage, increasing ulcer risk [7]. Experimental work by Husain showed irreversible tissue injury can occur within hours of continuous pressure [8]. Vulvar ulcers must be differentiated from infectious or autoimmune causes, as Kirshen and Edwards recommend, using history and clinical context [9]. The close association with splint placement and local necrosis supported a pressure ulcer diagnosis here. Biomechanical studies by Lindan et al. revealed that curved areas like the groin crease are prone to focal pressure, particularly without adequate padding, explaining the vulnerability caused by rigid splints [10]. Management requires a multidisciplinary approach. Initial care includes pressure relief, wound dressings, and infection control, with surgical debridement and flap closure for severe cases. Our patient underwent serial debridement and secondary closure with local flaps. The Thomas splint was replaced by an above-knee slab to avoid further vulvar pressure, and surgical fixation was delayed until healing allowed safe positioning [5]. In summary, this case illustrates a rare but preventable orthopedic complication in a medically complex patient. Vigilant pressure monitoring, especially in immobilized patients with conditions like sickle cell anemia, along with staff education and early intervention, can reduce device-related pressure ulcers in unusual sites such as the vulva.

This case highlights a rare but significant complication of Thomas splint application in a patient with sickle cell disease: A pressure ulcer over the vulva due to prolonged and unmonitored splint compression. Early recognition and a multidisciplinary approach to management, including pressure offloading, wound care, surgical intervention, and tailored hematological support, are crucial in such complex cases. Vigilant nursing care, regular inspection of pressure points, and prompt reporting of discomfort can prevent such complications, especially in patients with underlying risk factors such as sickle cell disease. Moreover, thoughtful positioning and patient-specific modifications in immobilization techniques are essential when using traditional splinting devices for extended durations.

Healthcare providers must be aware of atypical pressure ulcer sites, such as the vulva, particularly in immobilized and high-risk patients. Proper device placement, routine skin checks, and multidisciplinary care are crucial for prevention and successful management of such rare complications.

References

- 1.Bergstrom N, Horn SD, Smout RJ, Bender SA, Ferguson ML, Taler G, et al. The national pressure ulcer long-term care study: Outcomes of pressure ulcer treatments in long-term care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:1721-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Mancoll JS, Phillips LG. Pressure sores. In: Achauer BM, Erikson E, Guzuron B, Coleman J 3rd, Russell R, Vander Kolk C, editors. Plastic Surgery. Vol. 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc.; 2000. p. 447-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Conde Montero E, Martínez Gómiz JM, De La Cueva Dobao P. The vulva: An uncommon presentation of a pressure ulcer. Wounds 2017;29:E28-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Rakic VS, Colic MM, Lazovic GD. Unusual localisation of pressure ulcer--the vulva. Int Wound J 2011;8:313-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Rathore FA, New PW, Waheed A. Pressure ulcers in spinal cord injury: An unusual site and etiology. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2009;88:587-90. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Monfort JB, Senet P. Leg ulcers in sickle-cell disease: Treatment update. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle) 2020;9:348-56. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Taylor JG 6th, Nolan VG, Mendelsohn L, Kato GJ, Gladwin MT, Steinberg MH. Chronic hyper-hemolysis in sickle cell anemia: Association of vascular complications and mortality with less frequent vasoocclusive pain. PLoS One 2008;3:e2095. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Husain T. An experimental study of some pressure effects on tissues, with reference to the bed-sore problem. J Pathol Bacteriol 1953;66:347-58. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Kirshen C, Edwards L. Noninfectious genital ulcers. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2015;34:187-91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Lindan O, Greenway RM, Piazza JM. Pressure distribution on the surface of the human body. I. Evaluation in lying and sitting positions using a “Bed of springs and nails”. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1965;46:378-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]