Rarity of the intraosseous venous malformation of the long bones often results in misdiagnosis and requires a multidisciplinary approach for early diagnosis and management.

Dr. Rohit Prasad, Department of Orthopaedics, Central Institute of Orthopaedics, Vardhman Mahavir Medical College and Safdarjung Hospital, New Delhi, India. E-mail: rhean87@gmail.com

Introduction: Venous malformations are congenital lesions that occur due to a defect in vascular embryogenesis. Intraosseous venous malformations involving long bones are quite rare, as evidenced by limited case reports and series available in the literature.

Case Report: We present one such case of a young female who presented with chronic pain in the leg for 2 years and difficulty in walking. The clinical and radiological evaluation, including computed tomography angiography, confirmed the diagnosis of intraosseous venous malformation of the tibia. The lesion was managed initially by sclerotherapy and endovenous laser ablation by the intervention radiologist; however, the bony lesion required prophylactic intramedullary nailing in view of persistent pain affecting her daily activities.

Conclusion: The case highlights the rarity of the intraosseous venous malformation of long bones, which often results in misdiagnosis and requires a multidisciplinary approach in diagnosis and treatment for an optimal outcome.

Keywords: Low flow venous malformation, computed tomography angiography, tibia nailing, sclerotherapy, intraosseous venous malformation.

Vascular malformations are rare congenital lesions that occur due to a defect in vascular embryogenesis. They are always present at birth but may not be clinically evident at that time. They usually enlarge proportionately with the growth of the child, but a sudden increase can be seen secondary to trauma, puberty, pregnancy, infection, thrombosis, or any surgical intervention [1]. The extremity venous malformation has an associated intraosseous involvement in 18% of the cases. Multiple bone involvements are seen in almost 36% of intraosseous venous malformation [2]. The majority of the intraosseous venous malformations described in medical literature are seen in craniofacial bones or bodies of the vertebrae [3-5]. There are only a few reports affecting long bones [6-12]. Furthermore, the characteristic radiological appearance, which is seen in the skull and spine, is lacking in long bones, thereby presenting a diagnostic challenge. We report one such case of venous malformation of the extremity with intraosseous involvement of the tibia in a young female.

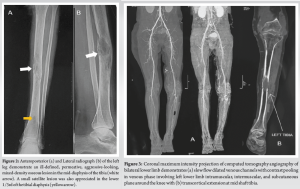

An 18-year-old female presented to the orthopedic outpatient clinic with pain in the left leg and difficulty walking for the past 2 years. There was a history of trivial trauma 2 years ago, which was managed with analgesics and anti-inflammatory medications. The pain was localized to the middle of the leg, mild-to-moderate in intensity, dull aching in character, and was aggravated by prolonged walking and relieved on rest and with medications. There was no history of fever, weight loss, or any other constitutional symptoms. There was a history of soft-tissue swelling involving the left thigh and knee since birth, which progressed over time, but the patient had not taken any treatment for the same. On physical examination, dilated tortuous veins with a soft blue mass were present around the distal left thigh and knee, suggesting venous malformation (Fig. 1).

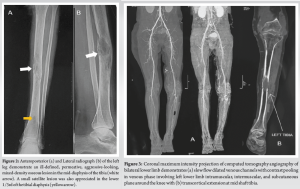

There was mild swelling in the middle of the leg with deep tenderness present. The local temperature was normal, with a full range of motion at the knee and ankle. There was no palpable lymph nodes around the popliteal or inguinal region, with no limb length discrepancy. The blood investigations, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, were within normal limits. The patient presented to us with the radiographs and non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). The anteroposterior (Fig. 2a) and lateral view (Fig. 2b) radiograph of the leg demonstrated a permeative intraosseous mixed density lesion (central lytic with peripheral sclerosis and presence of trabeculations/pseudo trabeculations) involving the lower half of the diaphysis, most predominant at mid diaphysis (Modified Lodwick pattern IIIB: Aggressive lesion). The mid-diaphyseal lesion appeared to be marrow-based with cortical erosion, except for the anterior cortex, which was spared. No pathological fracture or periosteal reaction was demonstrated.

The non-contrast MRI demonstrated altered marrow signal intensity in the mid and lower shaft of the tibia, which was hypointense on T1 and intermediate to hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The lesion extension into adjacent soft tissue was noted; however, no muscle edema, intermuscular fluid, or subcutaneous edema was noted. Since the patient had a congenital soft-tissue venous malformation in the distal thigh and knee, and as there were no clinical features suggestive of infection, a provisional diagnosis of intraosseous venous malformation was made. Subsequently, the diagnosis was confirmed using computed tomography (CT) angiography, which showed slow flow dilated venous channels with contrast pooling in venous phase involving left lower limb intramuscular, intermuscular, and subcutaneous plane around the knee (Fig. 3a) with transcortical extension at mid-shaft tibia (Fig. 3b).

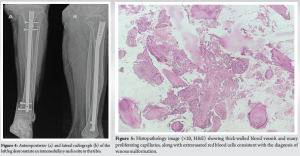

The patient was managed with sclerotherapy and endovenous laser ablation by the intervention radiologist. She was also advised to wear protective weight-bearing and compression stockings. Soft-tissue venous malformation responded to the treatment significantly; however, pain in the leg was persistent. The option of radiofrequency ablation of the intraosseous venous malformation was suggested; however, the procedure could not be done because of the economic constraints. As the pain was unremitting, limiting her activities of daily living, and a lytic lesion which involved more than 2/3rd of the cortex, the decision to perform prophylactic nailing was undertaken after pre-operative embolization (Fig. 4).

Intraoperatively, the intramedullary reaming content was sent for histopathology, which further confirmed our diagnosis (Fig. 5). The patient was allowed full weight bearing after 48 h of surgery. At 1-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic and was able to perform all her routine activities.

The International Society for the Study of Vascular Anomalies has classified vascular anomalies into either vascular tumors, such as hemangioma, or vascular malformations [13,14]. These vascular malformations are further divided into high-flow or low-flow lesions. Any lesion with an arterial component is considered a high-flow lesion. It can also be classified anatomically into capillary, venous, lymphatic, arterial, or their combinations. These vascular malformations can sometimes be associated with various syndromes such as Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) or Parkes–Weber syndrome (PWS) [13]. In KTS, there are capillary or venous malformations associated with bony and soft-tissue hypertrophy in the same limb. PWS also has the same characteristics, along with high-flow vascular malformations. In our case, it was a low-flow venous malformation, and there was no soft tissue or bony hypertrophy, which is seen in KTS and PWS. The common clinical presentation of intraosseous venous malformation of the extremity is pain, pulsating mass, skin ulceration, bony overgrowth, and enlargement of the draining vein [2,9,15]. The soft-tissue venous malformation with associated bony involvement is often seen in the diaphysis of long bone [6-11], as was also seen in our case. The radiographic findings include multiple smooth osteolytic or lucent serpiginous lesions involving the cortex and medulla [2,9]. However, in our case, it presented as a permeative lesion in the diaphysis mimicking an aggressive osseous lesion. Large intraosseous involvement can result in decreased bone density and increased risk of fractures. CT angiography and three-dimensional reconstruction images are helpful in the diagnosis, follow-up, and treatment, as was seen in our case. The intraosseous venous malformation typically appears as contrast-enhancing multiple small osteolytic lesions or a single large cavitary lesion in the medulla with or without cortical destruction. The MRI helps in distinguishing the high-flow and low-flow malformations and determining the relationship to adjacent anatomic structures. The characteristic phleboliths are also seen in venous malformations.

The management of vascular malformation requires a multidisciplinary approach, and treatment is usually conservative [16]. Various options of treatment are symptomatic treatment with compression stockings and analgesia, embolization, and/or surgical resection [17]. Embolization alone as a treatment for intraosseous venous malformation is associated with a high risk of recurrence [18]. The surgical treatment is also often associated with incomplete resection and local recurrence, along with the risk of profuse bleeding [17]. Thus, a combination of surgical and interventional radiological techniques gives the best results, as highlighted in our case, where a multidisciplinary approach was utilized to treat the intraosseous and soft tissue venous malformations.

The intraosseous venous malformation of long bones is quite rare and often poses challenges in diagnosis. The chronic history and atypical radiographic changes can be confused with other aggressive lesions such as osteomyelitis or bone tumors. Hence, a high index of suspicion is required in patients presenting with bony lesions associated with soft tissue lesions in the extremity. A multidisciplinary approach in a specialized center is required for the timely diagnosis and optimal treatment of these lesions.

The chronic symptoms and aggressive radiographic appearance on radiographs can be present in cases of intraosseous venous malformation of long bones. A high index of suspicion, along with a multidisciplinary approach, is required to manage these cases.

References

- 1. Enjolras O, Mulliken JB. The current management of vascular birthmarks. Pediatr Dermatol 1993;10:311-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Do YS, Park KB, Park HS, Cho SK, Shin SW, Moon JW, et al. Extremity arteriovenous malformations involving the bone: Therapeutic outcomes of ethanol embolotherapy. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2010;21:807-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Wenger DE, Wold LE. Benign vascular lesions of bone: Radiologic and pathologic features. Skeletal Radiol 2000;29:63-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Ogose A, Hotta T, Morita T, Takizawa T, Ohsawa H, Hirata Y. Solitary osseous hemangioma outside the spinal and craniofacial bones. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2000;120:262-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Sung MS, Kang HS, Lee HG. Regional bone changes in deep soft tissue hemangiomas: Radiographic and MR features. Skeletal Radiol 1998;27:205-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Knych SA, Goldberg MJ, Wolfe HJ. Intraosseous arteriovenous malformation in a pediatric patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1992;276:307-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Matsuyama A, Aoki T, Hisaoka M, Yokoyama K, Hashimoto H. A case of intraosseous arteriovenous malformation with unusual radiological presentation of low blood flow. Pathol Res Pract 2008;204:423-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Katzen BT, Said S. Arteriovenous malformation of bone: An experience with therapeutic embolization. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1981;136:427-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Savader SJ, Savader BL, Otero RR. Intraosseous arteriovenous malformations mimicking malignant disease. Acta Radiol 1988;29:109-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Nancarrow PA, Lock JE, Fellows KE. Embolization of an intraosseous arteriovenous malformation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1986;146:785-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Wang HH, Yeh TT, Lin YC, Huang GS. Imaging features of an intraosseous arteriovenous malformation in the tibia. Singapore Med J 2015;56:e21-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Aravindasamy M, Harshavardhan JK. A rare case of distal humerus intraosseous arteriovenous malformation. J Orthop Case Rep 2019;9:43-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Mulliken JB, Glowacki J. Hemangiomas and vascular malformations in infants and children: A classification based on endothelial characteristics. Plast Reconstr Surg 1982;69:412-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Finn MC, Glowacki J, Mulliken JB. Congenital vascular lesions: Clinical application of a new classification. J Pediatr Surg 1983;18:894-900. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Boyd JB, Mulliken JB, Kaban LB, Upton J 3rd, Murray JE. Skeletal changes associated with vascular malformations. Plast Reconstr Surg 1984;74:789-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Enjolras O, Deffrennes D, Borsik M, Diner P, Laurian C. Vascular “tumors” and the rules of their surgical management. Ann Chir Plast Esthet 1998;43:455-89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Young AE. Vascular malformations of the lower limb. In: Mulliken JB, Young AE, editors. Vascular Birthmarks: Hemangiomas and Malformations. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 1988. p. 400-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Perrelli L, Cina G, Cotroneo AR, Falappa P, Nanni L. Treatment of intraosseous arteriovenous fistulas of the extremities. J Pediatr Surg 1994;29:1380-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]