Early Surgical Intervention Is Critical: For complex talar neck fractures with open malleolar injuries and ankle subluxation, surgery within 10–12 hours minimizes infection and avascular necrosis risk. Single Anteromedial Approach When Feasible: This approach can provide adequate exposure for fixation, especially when extending from an existing open wound, but should be tailored to soft tissue condition and fracture pattern.

Dr. S Venkatesh Kumar, Assistant Professor, Department of Orthopaedics, Saveetha Medical College, Thandalam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu - 602 105, IndiaE-mail: mailvenkatesh91@gmail.com

Introduction: Talus fractures are uncommon and complex injuries associated with significant trauma and complications. The incidence of associated malleolar injury with talus fracture is rare.

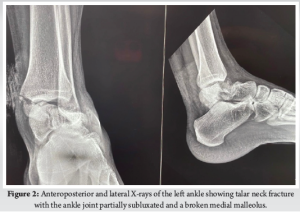

Case Report: We share this unusual case of a Hawkins type-3 talus neck fracture along with a serious Grade 3B medial malleolus fracture and ankle subluxation, which was treated with cleaning the wound, realigning the ankle, and surgery to fix the bones. Post-operatively, the wound was healthy and free of infection. Despite being told to avoid weight-bearing for three months, the patient lost follow-up after a month and started occasional partial weight bearing. During the 10th post-operative week, we found a mild degree of talar neck collapse and Hawkins sign radiologically. The range of motion for the ankle was dorsiflexion of 0–15° and plantar flexion of 0–30°, with minimal swelling and pain on weight bearing.

Conclusion: This case highlights the rarity and complexity of a talar neck fracture with ipsilateral medial malleolar fracture and ankle dislocation. Positive early outcomes were achieved through timely surgery within 10 h, careful soft tissue management, and appropriate fixation. The presence of a partial Hawkins sign post-operatively indicated preserved talar vascularity and reduced risk of avascular necrosis.

Keywords: Rare case of talus neck and medial malleolus fractures, compound injury, single anteromedial approach, ankle subluxation, good surgical outcome.

Anteromedial tibial plateau fractures are a rare fracture pattern that is mainly associated with high-energy trauma combined with knee hyperextension and varus stress [1]. This mechanism leads to compression force being transmitted between the medial femoral condyle and the anteromedial part of the tibial plateau, leading to either a small marginal fracture or a more severe depression at the articular surface [2]. Those fractures are usually marked by major soft tissue injuries, especially those of the posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), the posterolateral corner (PLC), and sometimes, the medial meniscus, as well as the bone damage[3]. Early and exact detection of such injuries is vital for both adequate diagnosis and surgical management [4]. Surgical treatment becomes necessary in circumstances when the injury encompasses a large anteromedial component. The ideal treatment in these situations is open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) since it promotes proper anatomical alignment in addition to re-establishing mechanical stability and restoring joint congruency. Furthermore, it enables early mobilization [5]. The success of surgical treatment relies very much on choosing the appropriate surgical approach and repairing technique, which must be altered to match the morphology and location of the fracture [6]. For instance, the anteromedial approach provides direct and effective access to the fracture site when the fracture line runs along the anteromedial surface of the tibia [6]. Although more complicated fracture patterns may call for extra posterolateral or anterolateral incisions to provide sufficient exposure and reduction [6], this approach is usually used in solitary simple Schatzker type IV fractures. Herein, we report a case of anteromedial tibial plateau fracture treated with ORIF using an anteromedial method and an L-shaped locking compression plate (LCP) fixation. The purpose of this article is to report an unusual case of anteromedial tibial plateau fracture with arcuate fracture but with no significant ligament injury. We describe in detail the treatment and long-term follow-up for this uncommon subtype of fracture.

Initial patient assessment

We present a case of a 44-year-old male who has been medically free.

The patient presented to our facility after sustaining a hyperextension injury to the left knee by being kicked by a horse 1 day before presentation.

The patient presented with left knee pain and with inability to bear weight.

Presenting symptoms

Patient presented with left knee pain and with inability to bear weight.

Physical examination

Upon examination, the patient was hemodynamically stable, conscious, alert, and oriented. Local knee examination revealed a mild bruise over the anterior and medial surface of the knee, no open wounds, and moderate swelling. The patient’s compartments were soft and compressible, and distal neurovascular examination was intact. Tests for ligament stability were not conducted in the acute setting.

Diagnostic evaluation

Imaging studies were done, including plain radiographs and computed tomography (CT), which revealed anteromedial rim fracture with anterior tibial eminence fracture of the left tibia and head of fibula fracture (arcuate sign) (Fig. 1 and 2). Although CT imaging provided adequate bony detail, no magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed preoperatively to assess soft tissue structures. The presence of a fibular head fracture (arcuate sign), suggestive of possible PLC injury, was not explored further with advanced imaging due to financial considerations of the patient.

Initial therapeutic intervention

The patient consented to examination under anesthesia, along with ORIF of the left tibial plateau and possible ligament repair if indicated.

After swelling subsided, the patient was taken to the operating theater and, under spinal anesthesia, the patient was placed in the supine position and a left thigh tourniquet applied.

Examination under anesthesia or suspected ligament injury, including anterior and posterior drawer test, external rotation recurvatum, and tibial dial test, varus and valgus test were all negative, omitting the need for ligament repair.

Operative details

Prepping and draping were done in a sterile manner, and an anteromedial approach to the tibial plateau was used. Fracture exposed, and hematoma evacuated. There was an anteromedial plateau fracture, minimally displaced, and an anterior shell fracture not involving the articular surface. Under C-arm guidance, fracture reduction was done, and a 3.5 LCP L-shaped plate was placed on the anteromedial aspect. Three fully threaded cancellous screws were inserted proximally and 2 fully threaded locking screws were inserted in the shaft. Plate position was checked on anteroposterior and lateral C-arm views, which confirmed reduction and fixation. The anterior shell fracture was too small to be captured; thus, it was left intact (Fig. 3).

Then, the tourniquet was deflated. Hemostasis achieved. Closure is done in layers. Pressure dressing applied, and the patient placed on a knee immobilizer. The patient was shifted to the recovery room in a stable condition.

Postoperative course

Postoperatively, the patient’s knee was immobilized in full extension using a hinged knee brace for the first 4 weeks to protect the fixation and facilitate early soft tissue healing. Passive range of motion (ROM) exercises was initiated at 4 weeks postoperatively, progressing to active-assisted and active ROM under supervised physiotherapy. Quadriceps strengthening and closed-chain exercises were gradually introduced between weeks 6 and 8. Partial weight bearing was permitted at 8 weeks, with progression to full weight bearing by 12 weeks, contingent upon radiographic evidence of healing. Throughout rehabilitation, emphasis was placed on joint stability, proprioceptive training, and return-to-function assessment tailored to the patient’s activity level. The patient was followed up in a 7-month period. In the last visit, the surgical scar was completely healed, the patient regained full knee ROM and was able to fully bear weight on it, and resumed his daily activities and job without complaining of pain. Patient was examined for ligamentous injuries which all were within normal range (Fig. 4 and 5).

The combination of talar neck fracture and ankle subluxation, along with ipsilateral medial malleolar fracture, is exceptionally rare. Very few cases have been reported until now [4,5]. Numerous reports have been made of complications, such as osteonecrosis, collapse, malunion, post-traumatic arthritis, and discomfort [3]. The time of definitive fixation depends on multiple factors, including fracture comminution and subtalar dislocation/subluxation [6,7]. Talus fractures that happen with a malleolar fracture have a lower chance of avascular necrosis (AVN) because the ligament-capsule complex between the broken piece and malleolus is still intact, which helps keep the blood supply and soft tissue healthy. In our case, we operated on an emergency basis within 10 h of injury due to associated fracture comminution, open soft tissue injury, and unreduced ankle subluxation to minimize the risk of future avascular necrosis. A retained broken guide wire during medial malleolus fixation was decided not to remove given its harmless intramedullary position and to prevent the further soft tissue damage that will incur during the extraction process that will increase the overall operative time and chances of infection. Although asymptomatic, this intraoperative event underscores the need for caution during hardware placement and raises potential concerns for future procedures. Post-operative x-rays revealed a partial Hawkins sign in the central and medial region of the talar dome, which is reliable evidence of talus vascularity after fracture and suggests that the chances of AVN are unlikely [8,9]. Our case was managed without CT or MRI, which the patient declined given the patient’s poor socio-economic status. While this limited detailed fracture assessment, it emphasizes the role of clinical judgment and standard radiographs in urgent surgical decision-making when advanced imaging is unavailable. The present standard for treating talus neck fractures is to use the anteromedial and anterolateral dual incision techniques [6]. In our case, we used the open medial wound proximally and extended the incision anteromedially and distally. Open fractures, which are frequently accompanied by soft tissue contamination and stripping, were discovered to have a 25% deep infection risk in open talus injuries [10]. The emergency reduction of dislocation, limb elevation, appropriate antibiotic administration, and tension-free suturing of the wound can all help to reduce soft tissue and wound problems, such as skin necrosis, infections, and poor wound healing [6]. Our patient showed no signs of a superficial or deep surgical site infection after surgery. While the single anteromedial approach was effective in our case, further randomised comparative studies with standard dual-incision techniques will be required to study the relative benefits or limitations of this approach. Several studies [6] have found a correlation between poor functional results and increasing injury severity. Although our patient lost contact after a month and began intermittent partial weight-bearing, the patient had better functional results. Talar neck malunion rates can range from 20% to 37%, while talar neck nonunion rates are uncommon (5% each) [7]. On the X-ray taken in the 10th week following surgery, there was no sign of talar neck malunion in our case. Despite instructions for strict non-weight bearing, the patient began early partial weight bearing. This sub-optimal compliance is explained by the poor socioeconomic status, cultural belief, long travel distance from their rural area to the hospital etc. This introduces a variable in outcome interpretation and underscores the importance of understanting the patient’s socio-economic condition. Post-traumatic subtalar arthritis is a typical long-term complication in such cases [7]. Our case requires a long-term follow-up since post-traumatic arthritis progresses over time. Our patient discontinued follow-up after one month, returning only at the 10th week yet presented with good clinical and functional outcome given the complexity of the case presentation. This highlights the challenges of ensuring long-term monitoring in trauma cases, especially in socioeconomically constrained populations.

The case study demonstrates the intricacy and uncommonness of a talar neck fracture accompanied with an ipsilateral medial malleolar fracture and ankle dislocation. The positive early results were a result of timely surgical intervention within 10 h, careful soft tissue treatment, and suitable fixation procedures. Following surgery, a partial Hawkins sign showed up, which was positive because it showed intact talar vascularity and a decreased likelihood of AVN. To get the best results possible for severe talar injuries, this case emphasizes the significance of prompt therapy, careful surgical planning, and attentive follow-up.

- For complex fractures, early surgical intervention is necessary: In cases of talus neck fractures with accompanying open malleolar injuries and ankle subluxation, prompt surgical therapy within the golden window (preferably within 10–12 h) should be prioritized to reduce the risk of infection and avascular necrosis.

- Use of a single anteromedial method in certain situations: When possible, the single anteromedial approach can offer sufficient exposure for fixing fractures of the medial malleolus and talar neck, particularly when it extends from an open wound that already exists. Nonetheless, this strategy must to be taken into account depending on the soft tissue state and fracture pattern.

- Strict follow-up and monitoring following surgery: Regular post-operative follow-up is crucial because to the elevated risk of complications, such as AVN, collapse, and arthritis. Results may be compromised by noncompliance or early weight bearing, as in this instance. Particularly in lower socioeconomic contexts, tactics, such as patient education and community health worker follow-ups may increase compliance.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis and wound management: Broad-spectrum antibiotics and tension-free closure methods are essential for avoiding deep infections and problems from wound healing in open talar injuries.

- Autologous bone graft utilization: Useful bone pieces are frequently produced by appropriate fracture comminution; if sterile and viable, these can be successfully utilized for grafting during internal fixation.

References

- 1. Isaacs J, Courtenay B, Cooke A, Gupta M. Open reduction and internal fixation for concomitant talar neck, talar body, and medial malleolar fractures: A case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2009;17:112-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Court-Brown CM, Caesar B. Epidemiology of adult fractures: A review. Injury 2006;37:691-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ebraheim NA, Patil V, Owens C, Kandimalla Y. Clinical outcome of fractures of the talar body. Int Orthop 2008;32:773-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Radaideh AM, Audat ZA, Saleh AA. Talar neck fracture with dislocation combined with bimalleolar ankle fracture: A case report. Am J Case Rep 2018;19:320-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Verettas DA, Ververidis A, Drosos GI, Chatzipapas CN, Kazakos KI. Talar body fracture combined with bimalleolar fracture. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008;128:731-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Dodd A, Lefaivre KA. Outcomes of talar neck fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:210-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Vallier HA. Fractures of the talus: State of the art. J Orthop Trauma 2015;29:385-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Tehranzadeh J, Stuffman E, Ross SD. Partial hawkins sign in fractures of the talus: A report of three cases. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2003;181:1559-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Tezval M, Dumont C, Stürmer KM. Prognostic reliability of the Hawkins sign in fractures of the talus. J Orthop Trauma 2007;21:538-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Burston JL, Isenegger P, Zellweger R. Open total talus dislocation: Clinical and functional outcomes: A case series. J Trauma 2010;68:1453-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]