Inferior shoulder subluxation is a rarely described pathology in literature. It is often a result of imbalance of muscular forces. The treatment is simple and easily accessible. This article aims to raise awareness about this condition, its presentation and treatment for the orthopedic and radiological community.

Dr. Shrirang Godbole, Department of Orthopaedics, Bharati Vidyapeeth (Deemed to be) University Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: sgodbole4@gmail.com

Introduction: The glenohumeral joint, while offering a high degree of mobility due to its ball-and-socket design, is inherently unstable. Shoulder instability is particularly challenging in pediatric and adolescent populations, where presentations are often atypical and non-traumatic. Functional shoulder instability (FSI), especially when idiopathic and inferior in direction, is exceedingly rare and underrepresented in literature.

Case Report: We report a unique case of a 15-year-old female who presented with chronic, atraumatic left shoulder subluxation, persisting over 18 months. The patient experienced pain and limited range of motion but reported no history of injury. Multiple prior consultations yielded temporary relief with analgesics, and no definitive diagnosis was established. Clinical evaluation revealed limited active abduction and external rotation with no signs of ligamentous laxity or neurological involvement. Radiographic assessment demonstrated gross inferior subluxation of the humeral head. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography imaging confirmed intact soft tissue structures with mild joint effusion, anterior glenoid flattening, and a 6% glenoid bone loss. A diagnosis of inferior, non-positional, controllable idiopathic FSI was made, likely due to deltoid atony. Treatment and Outcome: Management included temporary immobilization and physiotherapy using the Watson multidirectional instability protocol focused on scapular motor control retraining. After 10 weeks, the patient showed marked improvement with restoration of overhead abduction and full external rotation. Radiographs confirmed proper joint alignment, and the patient resumed normal activities symptom-free.

Conclusion: This case highlights a rare presentation of inferior idiopathic FSI in an adolescent. Early recognition and structured rehabilitation can lead to excellent outcomes, avoiding unnecessary interventions. Increased awareness of such atypical presentations is essential for prompt diagnosis and effective non-operative management.

Keywords: Shoulder, functional instability, inferior subluxation, adolescence.

The glenohumeral joint, a ball-and-socket structure, provides extensive mobility in three dimensions due to its anatomical design. However, this freedom of motion comes with reduced stability, largely because the glenoid cavity is relatively shallow and does not offer strong passive containment. This structural feature makes the shoulder particularly prone to instability. Shoulder instability can be defined as undesirable translation of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa, leading to pain or discomfort [1]. Shoulder dislocation and recurrent instability are increasingly common in the pediatric and adolescent population [2]. Epidemiological data suggest the average incidence to be approximately 0.3/100,000 individuals in the adolescent age group [3]. Unlike in older populations, the underlying causes in pediatric cases are often unclear and may not involve any trauma, suggesting a potentially atraumatic origin [4]. Abnormal muscle patterning and ligamentous laxity play a pivotal role in such cases [5]. Shoulder instability is generally categorized into two types: Dynamic, which produces noticeable symptoms during voluntary movement, and static, which is typically asymptomatic and identified incidentally through radiological imaging [6]. Most existing studies concentrate on traumatic shoulder instability, particularly among adolescents aged 14–16, who are at higher risk for both initial dislocation and recurrence. This group also tends to experience higher failure rates of both surgical and non-surgical treatments and may develop associated structural injuries such as Hill–Sachs lesions or labral tears [7]. By contrast, spontaneous or non-traumatic shoulder instability in younger children remains a relatively unexplored area. Studies usually find a significant event requiring reduction with later recurrence [7]. Some studies have blamed post-injection deltoid fibrosis leading to shoulder dislocations [8]. Challenges are observed when the patient has no significant inciting factor and non-emergent symptoms. Diagnoses and treatment may be delayed causing stress to the patient. We present one such case of shoulder subluxation with delayed diagnosis which was easily treated with a structured rehabilitation program.

A 15-year-old female reported to the outpatient department (OPD) with pain over the left shoulder associated with restricted mobility of the same shoulder. She was suffering from the same over a period of last 1½ years. She reported no history of trauma or any prior significant physical insult to the shoulder. She had consulted multiple doctors and specialists in her home city. She was treated with analgesics and muscle relaxants for the same. The symptoms were relieved intermittently. Examination in the OPD on presentation revealed restriction of active abduction of the shoulder to 30°. External rotation was also restricted to 40°. The patient had adapted to her condition and was employing torso rotations along with elbow and wrist movements to fulfil her daily needs. The contour of the left shoulder had noticeably flattened on comparison with the right. Sulcus and Gagey signs were negative. Neurological examination showed no significant abnormality. An interesting finding revealed that she was able to voluntarily “click” (reduce) her shoulder after which her active range of motion would improve by 10–15°. The Beighton score for the patient was 4/9 and the other shoulder was normal on clinical examination. The patient was then investigated radiographically which revealed a gross inferior subluxation of the shoulder. Further investigations were carried out which included a detailed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan and a limited computed tomography (CT) scan. The imaging findings have been included below. She was never investigated radiographically, hence comparison with any previous reports was not possible. Based on the radio-clinical examination, a provisional diagnosis of Inferior non-positional, controllable functional shoulder instability (FSI) due to idiopathic deltoid atony was thought to be the best fit in this scenario. The patient’s shoulder was placed in an arm sling for immobilization. Immediate physiotherapy rehabilitation was carried out. A thorough follow up was ensured.

Imaging findings

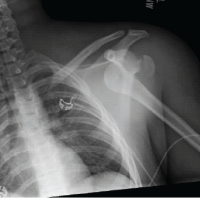

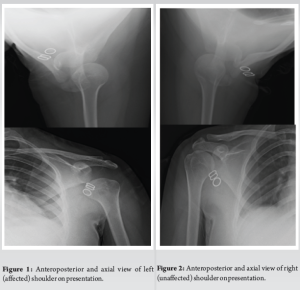

Anteroposterior (AP) radiography of the left shoulder demonstrated complete dissociation between glenoid and humeral head (Fig. 1). This led to a growing suspicion of the patient being a habitual shoulder dislocater. Owing to the limited abduction of the shoulder, a Velpau axillary view was carried out. The AP positioning of the humeral head was perceived to be within normal limits (Fig. 1). Opposite side radiographs were normal (Fig. 2).

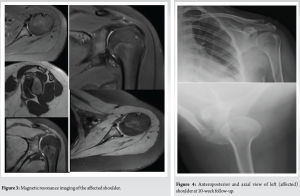

CT scan comparison with the opposite shoulder showed AP diameter of the left glenoid measured 19.7 mm. AP diameter of the right glenoid measured 21 mm. Comparative glenoid bone loss was pegged at 6%. There was mild flattening of the anterior margin of the glenoid. There was no scapular dyskinesia. The glenohumeral articulation was normal in the supine position on CT imaging. MRI revealed mild joint effusion with intact labrum, long head of the Biceps, and rotator cuff. The anterior and posterior bands of IGHL were intact.

Treatment and outcome

Vertical humeral traction was reduced in an arm sling; there is no need for any reduction manoeuvers [9]. The Watson rehabilitation protocol was followed. It advises retraining specific scapular motor control before any rotator cuff/deltoid strengthening [10,11]. At the end of a 10-week period, follow-up radiographs revealed that the humeral head had been repositioned into the glenoid (Fig. 3 and 4), and the active range of motion had significantly improved to 90° abduction with possible overhead abduction. External rotation had also improved to 80°.

The patient was then gradually weaned from the arm pouch and is now able to carry out her domestic, scholastic, and recreational activities without pain. The patient also has relief from the irksome “clicking” of her shoulder.

Inferior shoulder subluxation was described as a “troublesome complication” in 1921 by Cotton [12]. The Stanmore classification system groups shoulder instability into three poles: Traumatic (type I), atraumatic (type II), and muscle patterning (type III). Adolescents are more likely to have a combination of the three etiologies [13]. Abnormal muscle patterning arises due to disorganization in normal recruitment of muscles around the shoulder articulations, thus leading to shoulder instability [14]. Atraumatic shoulder instability without ligamentous laxity was termed FSI. It was grouped into four classes – positional, non-positional, controllable, and non-controllable [15]. Unidirectional and posterior were found to be the most common (78%), triggered by the shoulder in a flexed and internally rotated position. This was followed by Anterior (17%) and multidirectional instability (MDI) (6%). This case could be classified as controllable non-positional FSI, which was detected in only 11% cases of the cited study. To the best of our knowledge, there was no description of isolated inferior FSI in any other study. FSI often did not receive the required treatment with 14% cases never receiving any physiotherapy. Controllable FSIs are underdiagnosed, and the patients often suffer from greater morbidity. These cases are best managed non-operatively and there is very low potential for permanent structural damage if tackled early on [16]. Research shows the Watson MDI program is more beneficial than the Rockwood program in tackling shoulder instability. The same was used in this case. We present this case as an atypical, undescribed finding which will aid others in the diagnosis of similar cases and will help to reduce morbidity in such patients.

This patient had an underlying FSI, which was missed for a prolonged period by multiple clinicians. The patient’s symptoms improved dramatically after instituting a proper rehabilitation protocol. Follow-up radio-clinical examination proved the success of the treatment method. Watson’s MDI program proved to be thoroughly helpful in her treatment.

Taking into consideration the delayed diagnosis of this patient and the paucity of literature describing this condition, clinicians need to have a higher degree of suspicion so that such cases are not routinely misdiagnosed. Prompt diagnosis and treatment help to reduce patient morbidity and will stimulate others to report about this condition, thus raising awareness and spurring research about the same.

References

- 1.Nicolozakes CP, Li X, Uhl TL, Marra G, Jain NB, Perreault EJ, et al. Interprofessional inconsistencies in the diagnosis of shoulder instability: Survey results of physicians and rehabilitation providers. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2021;16:1115-25. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Goldberg AS, Moroz L, Smith A, Ganley T. Injury surveillance in young athletes: A clinician’s guide to sports injury literature. Sports Med 2007;37:265-78. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Longo UG, Salvatore G, Locher J, Ruzzini L, Candela V, Berton A, et al. Epidemiology of paediatric shoulder dislocation: A nationwide study in italy from 2001 to 2014. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:2834. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Zacchilli MA, Owens BD. Epidemiology of shoulder dislocations presenting to emergency departments in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2010;92:542-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Hill B, Khodaee M. Glenohumeral joint dislocation classification: Literature review and suggestion for a new subtype. Curr Sports Med Rep 2022;21:239-46. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Langlais T, Barret H, Le Hanneur M, Fitoussi F. Dynamic pediatric shoulder instability: Etiology, pathogenesis and treatment. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2023;109:103451. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Leroux T, Ogilvie-Harris D, Veillette C, Chahal J, Dwyer T, Khoshbin A, et al. The epidemiology of primary anterior shoulder dislocations in patients aged 10 to 16 years. Am J Sports Med 2015;43:2111-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Shanmugasundaram TK. Post-injection fibrosis of skeletal muscle: A clinical problem. A personal series of 169 cases. Int Orthop 1980;4:31-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Pritchett JW. Inferior subluxation of the humeral head after trauma or surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1997;6:356-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Watson L, Warby SA, Balster S, Pizzari T, Lenssen R. The treatment of multidirectional instability of the shoulder with a rehabilitation program: Part 1. Shoulder Elbow 2016;8:271-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Watson L, Warby S, Balster S, Lenssen R, Pizzari T. The treatment of multidirectional instability of the shoulder with a rehabilitation programme: Part 2. Shoulder Elbow 2017;9:46-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Cotton FJ. Subluxation of the shoulder-downward. Boston Med Surg J 1921;185:405-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Jaggi A, Lambert S. Rehabilitation for shoulder instability. Br J Sports Med 2010;44:333-40. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Jaggi A, Noorani A, Malone A, Cowan J, Lambert S, Bayley L. Muscle activation patterns in patients with recurrent shoulder instability. Int J Shoulder Surg 2012;6:101-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Moroder P, Danzinger V, Maziak N, Plachel F, Pauly S, Scheibel M, et al. Characteristics of functional shoulder instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020;29:68-78. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Rawal A, Eckers F, Lee OS, Hochreiter B, Wang KK, Ek ET. Current evidence regarding shoulder instability in the paediatric and adolescent population. J Clin Med 2024;13:724. [Google Scholar | PubMed]