Bone tumors can present atypically as mimicking commonly encountered benign disease entities, and as such, compulsory radiological investigation must be emphasized to diagnose these anomalous conditions early, resulting in earlier detection and better outcomes for the patient.

Dr. Eshaan Mishra, Department of Orthopedics, SCB Medical College and Hospital, Cuttack, Odisha, India. E-mail: eshaanmishra271@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is one of the most commonly encountered bone tumors in any orthopedic surgeon’s routine practice. Although in most instances the age, sex, location, and clinical presentation are typical there is always a chance of encountering an atypical case with an anomalous presentation.

Case Report: Benign bone tumors such as GCT are often diagnosed with a symptomatology typical of bone tumors, however, there have been many reported cases wherein they were diagnosed incidentally as part of investigation into a different disease manifestation. These nuances are of more significance in case of GCT as it is a benign aggressive tumor and the prognosis after treatment is highly dependent on earlier diagnosis allowing for increased chances at limb salvage and functional restoration as compared to more radical treatment options. Lateral ankle sprain is a commonly encountered disease entity and, as such, enjoys a very benign progression with conservative management. Our patient was initially diagnosed on outpatient basis as a case of ankle sprain based on the history and clinical features, However, worsening of symptoms on conservative management prompted us toward the presence of a more sinister pathology. Subsequent radiological and histopathological investigations helped in the definitive diagnosis of GCT of calcaneus.

Conclusion: We present to you a case of calcaneal GCT masquerading as lateral ankle sprain which is a rare presentation and such cases need to be evaluated meticulously with respect to their diagnostic algorithm and treatment challenges.

Keywords: Calcaneus giant cell tumor, lateral ankle sprain, extended curettage, sandwich technique, foot and ankle, orthopedic oncology.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is one of the commonest benign bone tumors encountered by an orthopedic surgeon. It commonly affects females, and the peak incidence is seen in the third decade of life [1]. The tumor is commonly seen around the knee, with the ephiphysio-metaphyseal region of the distal femur being the most common site, followed by the proximal tibia. Distal radius is the 3rd most common site of occurrence [2]. These patients most commonly present with pain of variable severity that may be associated with a mass present from a few weeks to several months. There may be an antecedent history of trauma. Lateral ankle sprain is another clinical entity commonly encountered in the outpatient department (OPD) by orthopedicians. These patients present with pain and swelling in the lateral aspect of foot and ankle after an episode of twisting injury to the ankle. These symptoms may last from a few weeks to months. We present to you a rare case of calcaneal GCT masquerading as lateral ankle sprain in a 27-year-old female.

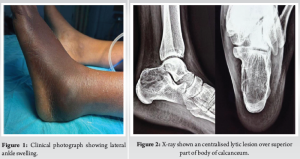

A 27-year-old female presented to OPD with complaints of swelling and tenderness in the lateral aspect of the left ankle and foot for 3 months. There is a history of twisting injury to the left ankle while riding a bicycle 3 months back, after which the patient noticed the swelling. The patient has received conservative management for lateral ankle sprain but, however, no radiographs were taken during such consultations. On clinical examination, there was a diffuse swelling involving the lateral aspect of the left ankle (Fig. 1) which was tender on palpation without any local rise of temperature. There is no history of any constitutional symptoms. Ankle and foot examination are within normal limits. On roentgenography (Fig. 2), we found an expansile, lytic lesion in the proximal aspect of the body of the left calcaneus. The lesion has a narrow zone of transition. There was no periosteal reaction, no matrix, no soft-tissue component. There was no sclerotic margin. Multiple septae appear to be traversing the length of the lesion, producing a trabeculated appearance. Radiologic evaluation of other body parts ruled out multicentric lesions.

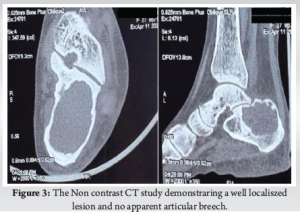

On the Non contrast CT scan (Fig. 3), we observed that there was thinning, but no breach in continuity, of the native bone cortices. The trabeculations observed on X-ray were not visualized in computed tomography (CT) cross sections. The articular surfaces did not appear to be involved.

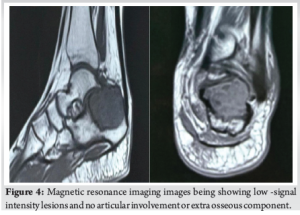

On magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Fig. 4), areas of low-signal intensity were observed on both T1- and T2-weighted images just below the region of the posterior facet which corresponded to the solid tumor component as was subsequently confirmed during surgery. There was a high-signal intensity region in the posterior aspect of the lesion, which was due to intratumoral hemorrhage. No marrow edema was observed. No fluid-fluid levels, classical of aneurysmal bone cysts, were observed. There was no extraosseous component or joint involvement. The lesion was visualized on short tau inversion recovery sequence and hence an intraosseous lipoma was ruled out.

A core needle biopsy with a Jamshidi needle was performed under local anesthesia from the lateral aspect of the ankle by the primary surgeon. The histopathological examination showed the presence of mononuclear stromal cells and osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells, conclusive with our diagnosis of GCT of the calcaneus.

The patient was planned for extended curettage through an extended lateral approach, and the cavity filled with autologous cancellous bone graft and bone cement by the Sandwich technique (Fig. 5). The immediate post-operative X-ray image is shown in Fig. 6.

Postoperatively, the patient was kept non-weight bearing for 6 weeks, followed by partial weight bearing up to 3 months, and allowed full weight bearing then onward. The patient was followed up at 3 months (Fig. 7), 6 months (Fig. 8), and 1 year (Fig. 9) for any evidence of recurrence or articular collapse.

Primary bone tumors of the foot are a rare occurrence [3]. In a study by Yan et al., [4] primary calcaneus tumors accounted for 35% of osseous foot tumors, and GCT of calcaneum consisted of <1% [5,6] of all calcaneal tumors. The usual age of occurrence in primary GCT of long bones is the 3rd decade of life, and is more common in females, which is similar to that observed for calcaneal GCT [1]. This rare site of occurrence poses unique diagnostic and prognostic challenges. In this case, a temporal delay in diagnosis occurred due to aligning of the patient’s chief complaints with a diagnosis of lateral ankle sprain, which is a commonly encountered condition. Calcaneal GCT has previously been reported as mimicking other common ankle pathologies such as heel pain [7]. A delay in diagnosis can result in worsening of prognosis for the patient, even leading to amputation of the foot [1], as GCT of foot bones is generally more aggressive as compared to that in long bones [8]. We also performed a skeletal survey to rule out any synchronous lesions as there are previous reported cases of multicentricity [9-11]. Roentgenographic evaluation in this case revealed findings classically attributed to GCT [12]. The computed tomography and MRI findings were also characteristic of GCT and were similar to those described in previous literature [2, 12-14]. As is universally acknowledged protocol, core needle biopsy was performed after all non-invasive diagnostic modalities and histopathological findings were characteristic of GCT [2]. A decision regarding extended curettage was taken after careful evaluation of the tumor dimensions and assessment of the host bone stock. Sandwich technique of bone grafting and bone cement application was performed in a conventional manner, as is the practice in most Campanacci grade 2 and grade 3 GCTs for adjacent joint preservation [15] (Table 1).

As seen in the literature, most patients presented with localized pain and swelling, with imaging revealing characteristic lytic lesions. Treatment across these cases has typically involved intralesional curettage, often augmented with bone grafts or cementation. The outcomes were generally favorable, with low recurrence reported during follow-up.

This case report highlights the unpredictable nature of primary bone tumors in terms of their location and presenting features. Orthopedicians must be vigilant of these rare presentations and must be thorough in evaluation to diagnose these conditions early. The value of radiological investigation in these scenarios cannot be overemphasized. An algorithmic approach to diagnosis can help in detection of these rare conditions. Treatment modalities must be considered on a case to case basis and must aim at preserving maximum functionality.

Thorough clinical and radiological investigation holds the key to accurate clinical diagnosis. Even the simplest of clinical conditions must be thoroughly evaluated. Protocols must be adhered to for commonly encountered symptom complexes and must be adhered to during routine practice. In case of bone tumors, the clinical presentations may not always be classical and in the cases, meticulous radiological and histopathological investigations are of paramount importance. Cases with anomalous presentations may be best referred to a surgeon with experience of managing such orthopedic oncology cases.

References

- 1. Dasan T, Vijay K, Satish C, Nagraj B, Nataraj B. Comprehensive case report of a giant cell tumor involving the proximal phalanx of the left great toe managed with fibular grafting. Int J Radiol 2012;14:1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Hosseinzadeh S, Tiwari V, De Jesus O. Giant cell tumor (osteoclastoma). In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk559304 [Last accessed on 2023 Jul 24]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kilgore WB, Parrish WM. Calcaneal tumors and tumor-like conditions. Foot Ankle Clin 2005;10:541-65, vii. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Yan L, Zong J, Chu J, Wang W, Li M, Wang X, et al. Primary tumours of the calcaneus. Oncol Lett 2018;15:8901-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:106-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Dahlin DC, Cupps RE, Johnson EW Jr. Giant-cell tumor: A study of 195 cases. Cancer 1970;25:1061-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Rodge R, Rodge S, Rao AK, Gadekar T. Clinico radiological presentation and management of giant cell tumour of calcaneum: A case report. J Clin Diagn Res 2023;17:PD04-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Patel R, Parmar R, Agarwal S. Giant cell tumour of the small bones of hand and foot. Cureus 2023;15:e42197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Dhillon MS, Prabhudev Prasad A, Virk MS, Aggarwal S. Multicentric giant cell tumor involving the same foot: A case report and review of literature. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:154-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Cummins CA, Scarborough MT, Enneking WF. Multicentric giant cell tumor of bone. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1996;322:245-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Li X, Guo W, Yang RL, Yang Y. Multicentric giant cell tumor: Clinical analysis of 9 cases. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2013;93:3602-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Chakarun CJ, Forrester DM, Gottsegen CJ, Patel DB, White EA, Matcuk GR Jr. Giant cell tumor of bone: Review, mimics, and new developments in treatment. Radiographics 2013;33:197-211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Galvan D, Mullins C, Dudrey E, Kafchinski L, Laks S. Giant cell tumor of the talus: A case report. Radiol Case Rep 2020;15:825-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Purohit S, Pardiwala DN. Imaging of giant cell tumor of bone. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:91-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kundu ZS, Gogna P, Singla R, Sangwan SS, Kamboj P, Goyal S. Joint salvage using sandwich technique for giant cell tumors around knee. J Knee Surg 2015;28:157-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]