This case report highlights the importance and advantage of proper pre-operative evaluation especially in dealing with complex trauma. The case report also emphasizes on the fact that following textbook and traditional methods may not always yield the best outcome.

Dr. Sanjay Pratheep, Junior Resident, Department of Orthopedics, K.L.E Dr. Prabhakar Kore Hospital and MRC, Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College, KLE Academy of Higher Education and Research, Belagavi, Karnataka, India. E-mail: sanjaypratheep16031995@gmail.com

Introduction: Femoral head fractures occur almost exclusively as a result of a traumatic hip dislocation. Due to the intrinsic anatomical stability of the hip, most of these injuries result from high-energy trauma. Treatment is typically an emergency surgery that includes the reduction of the dislocated hip under anesthesia to fix the fracture of the head of the femur and reduce dislocation. Treatment outcomes tend to be inconsistent, largely because of the fracture’s frequent association with pain, joint stiffness, and loss of function. Complications that are most commonly seen after femoral head fractures are osteonecrosis, osteoarthritis, and heterotopic ossification.

Case Report: A 39-year-old male came to casualty with an alleged history of road traffic accident with multiple fractures in bilateral upper limb, multiple rib fractures, and brachial plexus injury. Computed tomography of the pelvis with both hips was done, which showed a fracture of the left femoral head with a proximal fracture fragment found inside the acetabulum with posterior dislocation of the distal part - left femoral head fracture dislocation (Pipkin type I). Closed reduction of the hip joint failed; hence, open reduction using the Kocher–Langenbeck (KL) approach was carried out, head reduced, transfixed with guide wires, and fixed with three CC screws. On the last follow-up at the end of 1 year, the patient has regained full range of motion of the hip. Patient is able to squat, sit cross-legged, and is able to walk unaided.

Conclusion: The case discussed here is one of its kind, hence fracture was also reduced after reducing the hip joint through trochanterocephalic fixation with KL approach. Precise radiographic pre-operative evaluation and early fixation with early mobilization are the key factors to success in dealing with these complex fractures. Relying on standard and textbook methods may not always yield the best outcome.

Keywords: Femoral head fracture dislocation, proximal femur fractures, Pipkin classification, hip dislocation, osteonecrosis, osteoarthritis hip, Pipkin fractures, Kocher–Langenbeck approach.

Femoral head fractures occur almost exclusively as a result of a traumatic hip dislocation. Due to the intrinsic anatomical stability of the hip, most of these injuries result from high-energy trauma, typically in the form of automobile accidents (such as collisions and pedestrians being run over) or falls from a significant height [1]. Approximately two-thirds of patients are young adults, and associated injuries are extremely common, occurring in as many as 75% of the cases. Treatment is typically an emergency surgery that includes the reduction of the dislocated hip under anesthesia to fix the fracture of the head of the femur and reduce dislocation [2]. As a rule, the earlier the reduction, the better the outcome. Worse outcomes have been observed when the hip is reduced incongruently or more than 6 h after the injury, mainly due to the statistically significant increase in the rate of avascular necrosis of the femoral head [3,4]. Treatment outcomes tend to be inconsistent, largely because of the fracture’s frequent association with pain, joint stiffness, and loss of function. Complications that are most commonly seen after femoral head fractures are osteonecrosis, osteoarthritis (OA), and heterotopic ossification(4).

A 39-year-old male came to the casualty with an alleged history of a road traffic acciden 8 h ago. The patient, since then, has been complaining of pain in the left hip and thigh, deformity at the left hip, the patient is also unable to bear weight on the affected limb. On examination, the attitude of the limb was flexion, internal rotation, and adduction. Shortening of the left lower limb was noted. Tenderness is present over the proximal aspect of the left femur and hip. The range of movements is restricted at the left hip and knee joints. No wounds noted, peripheral sensations are found to be intact with no vascular injury. Computed tomography of the pelvis with both hips was done, which showed a fracture of the left femoral head with proximal fracture fragment found inside the acetabulum with posterior dislocation of the distal part – left femoral head fracture dislocation (Pipkin type I). X-ray imaging showed fractures of other limbs as follows (Fig. 1):

- Comminuted fracture of the left humerus shaft

- Comminuted fracture of the right middle 1/3rd clavicle

- Multiple rib fractures with minimal hemopneumothorax

- Comminuted fracture of body and neck of the right scapula

- Comminuted fracture of body of the left scapula

- Brachial plexus injury with neurodeficit in the right upper limb.

Procedure

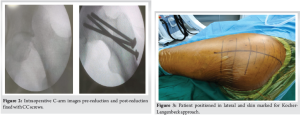

On the day of injury, the patient was explained the nature of the procedure, risks, and complications of the same, explained in his own vernacular language. Consent for surgery taken. Patient shifted to the operation theater and combined spinal epidural anesthesia was given. One trial for closed reduction was given, which was unsuccessful. The next day, the patient was taken up for open reduction, and Kocher–Langenbeck (KL) approach was taken to expose the femoral head as it was found posterior in relation to the acetabulum. The patient was put in lateral position, parts painted and draped. On table, a rent in the capsule and buttonholing of the head above the piriformis tendon was seen. The piriformis tendon was tagged and cut. Short external rotators were found to be torn. Palpation of the fragment, which was found lying inside the hip, revealed that the head was rotated and attached to the ligamentum teres. It was derotated back to its original position. On palpation, the fragment was very large and thus no attempt to cut the ligamentum teres was done. The hip was reduced and visualized under the image intensifier television (IITV) in the lateral position. The IITV images revealed a very congruent reduction. The fracture was then transfixed with three guide wires of cc screws (6.5 patially threaded) from the trochanter to the head. The direction of the wires was aimed at centring on the fracture fragments. The same was again confirmed under IITV in both anteroposterior and lateral views. On gently moving the hip through various degrees of motion, fixation of the fragment was found to be stable and anatomical. Partially threaded cc screws of appropriate lengths with washers were introduced over the guide wires. Again, the hip was put into maximum range of motion (ROM) and in all views, the fixation was found to be anatomical and stable. The operative wound was given a thorough 500 mL saline wash, and the wound was given a drain. The patient was hemodynamically stable postoperatively (Fig. 2-4).

Because of his associated other limb injuries, the patient was kept in bed for 6–8 weeks postoperatively. Active closed chain ROM of the hip was started from the 3rd day and increased as per the patient’s comfort. The patient was made to sit bedside by the 3rd week. Because of associated other limb injuries, the patient was kept non-ambulatory for 5 months postoperatively (Fig. 5).

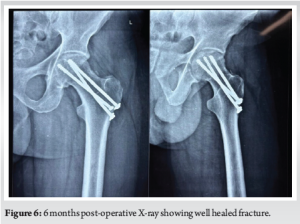

Follow-up X-rays were taken at 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year. On the last follow-up at the end of 1 year, the patient has regained full ROM of the hip. Patient is able to squat, sit cross-legged, and is able to walk unaided (Fig. 6 and 7).

Femoral head fracture-dislocations are associated with significant morbidity due to the complex nature of the injury. They are frequently accompanied by other fractures of the acetabulum or femoral shaft. The primary challenge in management is achieving anatomical reduction of both the femoral head and the hip joint. Early reduction is critical to minimize the risk of complications such as avascular necrosis, which can occur due to damage to the femoral head’s blood supply [5,6]. Closed reduction is the preferred treatment option when possible, as it avoids the morbidity associated with open procedures. However, this requires expertise in fracture reduction and proper imaging guidance to ensure optimal outcomes. In cases where closed reduction is not possible or if there is significant instability, open reduction and internal fixation may be required [7-9]. Early mobilization, followed by rehabilitation, is essential for restoring joint function and preventing long-term complications such as stiffness, OA, or chronic pain [10] Ongoing monitoring and follow-up are necessary to assess for signs of avascular necrosis or joint degeneration.

Femoral head fracture-dislocations are high-energy injuries requiring prompt and precise management to optimize outcomes. The case discussed here is one of its kind, hence fracture was also reduced after reducing the hip joint through trochanterocephalic fixation with KL approach. Precise radiographic pre-operative evaluation and early fixation with early mobilization are the key factors to success in dealing with these complex fractures. Relying on standard and textbook methods may not always yield the best outcome.

Even though this case is one of the most complex traumas we can expect to get and even though we did not follow the traditional protocol on how this case has to be approached, following principles of fracture reduction and fixation with early and safe mobilization did yield the most favorable outcome.

References

- 1. Alonso JE, Volgas DA, Giordano V, Stannard JP. A review of the treatment of hip dislocations associated with acetabular fractures. Clin Orthop Rel Res 2000;377:32-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Giordano V, Costa PR, Esteves JD. Luxações traumáticas do quadril em pacientes esqueleticamente maduros. Rev Bras Ortop 2003;38:462-72 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Clegg TE, Roberts CS, Greene JW, Prather BA. Hip dislocations–epidemiology, treatment, and outcomes. Injury 2010;41:329-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Foulk DM, Mullis BH. Hip dislocation: Evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2010;18:199-209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Özcan M, Çopuroğlu C, Saridoğan K. Fractures of the femoral head: What are the reasons for poor outcome? Turk J Trauma Emerg Surg 2011;17:51-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Stannard JP, Harris HW, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Functional outcome of patients with femoral head fractures associated with hip dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;377:44-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Schafer SJ, Anglen JO. The East Baltimore lift: A simple and effective method for reduction of posterior hip dislocations. J Orthop Trauma 1999;13:56-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Asghar FA, Karunakar MA. Femoral head fractures: Diagnosis, management, and complications. Orthop Clin North Am 2004;35:463-72. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Chen ZW, Lin B, Zhai WL, Guo ZM, Liang Z, Zheng JP, et al. Conservative versus surgical management of Pipkin type I fractures associated with posterior dislocation of the hip: A randomised controlled trial. Int Orthop 2011;35:1077-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Marecek GS, Routt ML Jr. Percutaneous manipulation of intra-articular debris after fracture-dislocation of the femoral head or acetabulum. Orthopedics 2014;37:603-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]