Femoral Neck System™ failures can occur at the barrel aperture and present major challenges during removal; this should be considered when selecting implants for young patients

Dr. Jude A Alawa, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, New York. E-mail: alawaj@hss.edu

Introduction: Femoral neck fractures in young adults are rare but carry a high risk of complications, including non-union and implant failure. The femoral neck system™ (FNS) is a newer fixation device designed to enhance mechanical stability while minimizing surgical morbidity. Limited reports exist on its failure modes. The purpose of this case report is to describe a unique failure of the FNS and the challenges encountered during revision surgery.

Case Report: A 21-year-old female sustained a basicervical femoral neck fracture and underwent fixation with the FNS and an additional headless screw at an outside institution. Seven months post-operatively, she developed progressive, atraumatic hip pain and was unable to bear weight. Imaging revealed non-union and implant failure at the aperture where the bolt and antirotation screw exit the plate barrel. Revision surgery included intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy and blade plate fixation. Removal of the broken FNS components was technically demanding and required trephination, leading to further compromise of the femoral head and neck bone stock.

Conclusion: This case highlights a rare failure mode of the FNS involving simultaneous failure of the bolt and antirotation screw at the barrel aperture. Surgeons should be aware of this potential complication and the technical challenges it may pose during implant removal and revision surgery. These considerations may influence implant selection and pre-operative planning, particularly in young patients at risk for non-union.

Keywords: Femoral neck system, femoral neck fracture, hip fracture, orthopedic trauma, implant complications, implant failure.

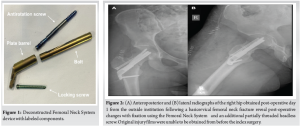

Femoral neck fractures in young adults only comprise 2–3% of all femoral neck fractures and often result from high-energy trauma [1]. Studies have shown an association between these fractures in young adults and high incidences of osteonecrosis and non-union [2-7]. Fixation strategies in young patients emphasize anatomic reduction, preserving blood supply, and stable fixation to reduce complications. Classic fixation methods include closed reduction and percutaneous pinning (CRPP) with cannulated screws and sliding hip screw (SHS). Complication rates after CRPP and SHS remain high, with studies showing the incidence of osteonecrosis at 14.3%, malunion at 7.1%, and implant failure at 9.7%, with complications correlated with increasing Pauwel’s angle [8]. The Femoral Neck System™ (FNS) (Fig. 1) is a fixation device that aims to reduce varus collapse risk, increase mechanical and rotational stability compared to CRPP, and decrease incision size and incidence of lateral thigh pain compared to SHS [9-12]. While the FNS aims to combine the benefits of CRPP and SHS while eliminating the challenges associated with each, reported outcomes from in vivo studies are limited. Recent meta-analyses comparing the FNS to other fixation strategies have reported favorable union rates and relatively low complication rates, including rare instances of implant failure. However, few reports have detailed the specific modes of failure or the intraoperative challenges that may arise during revision surgery [13,14]. We report a case of FNS implant failure in a young patient with a femoral neck fracture occurring within 1 year of surgery. The patient consented to the publication of her case.

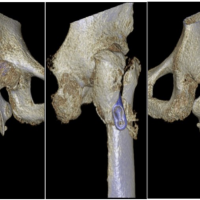

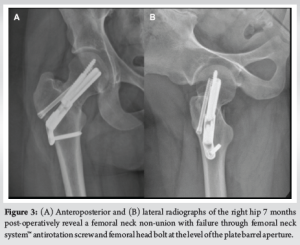

An active 21-year-old female sustained a right basicervical femoral neck fracture after being struck by a golf cart. She was treated at another institution using the FNS with an additional partially threaded headless screw (Fig. 2a and b). Seven months post-operatively, she developed progressive, atraumatic right hip pain with an inability to ambulate. She presented to our institution for evaluation. Radiographs demonstrated a right femoral neck non-union with implant failure through the bolt and antirotation screw at the level of the plate barrel aperture (Fig. 3a and b). She was consented for revision surgery with intertrochanteric valgus osteotomy and blade plate fixation.

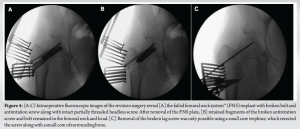

The patient had no relevant past medical history and no history of tobacco use. Her body mass index was 24 kg/m2. A non-union workup was non-contributory, and to our knowledge, there were no pre-existing risk factors for non-union. For the procedure, her previous lateral incision was used, and the FNS plate was easily visualized (Fig. 4a). The locking screw was removed from the plate, and the plate was removed with the head of the broken antirotation screw and a piece of the broken bolt. Proximal fragments of the broken lag screw and bolt remained in the femoral head (Fig. 4b), which were challenging to remove without causing further damage to the femoral head and neck. To remove the broken bolt, a threaded Steinmann pin was inserted manually into the bolt fragment, and the pin and bolt were extracted together. For the broken antirotation screw, a small core trephine was placed over the broken fragment to resect it along with a small core of surrounding bone from the femoral head and neck (Fig. 4c). Extracting the failed FNS was technically demanding, required sacrificing tenuous bone stock, and added approximately 60 min to the total operative time. The intact partially threaded headless screw was removed without difficulty after FNS removal.

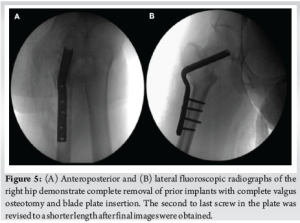

Next, a 20° intertrochanteric valgus closing wedge osteotomy and blade plate insertion was performed. An articulating tensioning device was used to maximize compression at the osteotomy site. Fluoroscopy revealed an acceptable position of all implants (Fig. 5a and b). Post-operatively, she underwent a supervised return-to-activity protocol consisting of partial (50%) weight-bearing with crutches for 8 weeks, following by gradual return to full weight-bearing with physical therapy over 2 weeks thereafter.

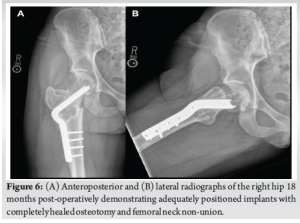

She has been followed for 18 months post-operatively. At the most recent follow-up, she has returned to full weight-bearing, along with competitive swimming and daily bicycling without pain. Radiographs demonstrate intact and appropriately positioned implants with completely healed non-union and osteotomy sites (Fig. 6a and b). She has a 2 cm limb length discrepancy, for which she uses a shoe lift.

We describe a case of FNS implant failure involving the antirotation screw and femoral head bolt, including a challenging removal and revision. It is important to alert surgeons to this failure mode, as it may impact pre-operative planning and implant selection. A multicenter case series of 125 patients treated with the FNS reported 2 cases (1.6%) of implant failure, but the failure sites were not specified [15]. In seven studies involving 473 FNS cases, no implant breakage was noted [16-22]. Several reports of FNS compromise exist in the FDA MAUDE database, though these often lack critical details and are not peer reviewed [23]. In this report, failure of both the bolt and the antirotation screw occurred where they exit from the plate barrel. In an analysis of SHS failure, the bending forces of the lag screw, analogous to the FNS bolt, increase along the implant from proximal to distal and reach a maximum at its intersection with the plate barrel [24]. In this case, that intersection occurred at, or very near, the patient’s fracture. Consequently, the shear forces at the fracture were concentrated near the point of maximal bending stress of the implant, likely contributing to failure at that location. Further, the bolt has an aperture on its superior surface, allowing for the antirotation screw to fit near its intersection with the plate barrel, which may have weakened the bolt and contributed to its failure at this level. The antirotation screw failed at the screw notch, placed at the same level as the end of the plate barrel, where the narrow caliber proximal third of the screw meets the larger caliber portion of the remaining screw. Biomechanically, this change in cross-sectional diameter may generate an area of stress concentration, which may have contributed to its failure at this location. In our case, the failed components were returned to the manufacturer for safety reporting in accordance with institutional protocol. We do not have access to a retrieval lab, and we did not receive a formal report or failure analysis from the manufacturer. In future cases, consultation with an implant retrieval laboratory may provide further insight into the failure mechanism and should be considered. In addition, no histopathological or advanced imaging analysis was performed on the resected bone. Such assessments may help characterize the biological integrity of bone at the failure site and its potential contribution to healing outcomes or implant performance. Beyond implant design, the patient’s non-union resulted in prolonged reliance on and loading of the implant. In a study of non-geriatric patients with femoral neck fractures treated with the FNS, the mean time to union was 2.86 months ±0.77, with 2 patients developing non-union [18]. Reported non-union rates for patients treated with FNS range from 1 to 10% [15,17,18,20-22]. Known risk factors for femoral neck non-union include high fracture angle (i.e., Pauwels Type III), initial fracture displacement, and inadequate reduction [2,25-29]. This patient had a displaced fracture (Garden IV) with a fracture angle of 48°, near the cut-off for a Pauwels Type III (50°). Of note, original injury films and intraoperative imaging from the index surgery were unavailable, limiting full assessment of reduction quality and fracture characteristics. However, initial post-operative imaging revealed a slight residual fracture gap inferomedially, which may have limited compression (Fig. 2a). Therefore, in a healthy patient without risk factors for non-union, the initial and non-anatomic reduction may have contributed to non-union and implant failure. While the fracture was reduced in slightly more valgus, post-operative imaging, as well as the operative report, revealed no evidence of implant malposition or mechanical error. Although it is not possible to confirm whether the implant was fully tightened at the time of surgery, the simultaneous failure of both the antirotation screw and bolt at the non-union site suggests fatigue loading as the likely mechanism. In a study of femoral neck non-union, 7 of 9 cases of non-union in patients with fixed-angle devices occurred in the setting of uncontrolled collapse and loss of bone stock [30]. Interestingly, in this case, there was relatively well-preserved bone stock and minimal femoral neck shortening along the line of the FNS bolt. In biomechanical studies, the FNS has performed similarly to SHS and superior to cannulated screws [9-11,31,32]. However, a single study found that cannulated screws have better biomechanical stability in fractures with non-anatomic reductions [33]. In clinical studies, the FNS has shown lower complication rates compared to cannulated screws and similar outcomes to SHS [16,18,19,21]. Compared to a SHS, the FNS is reported to be less invasive with a smaller incision, shorter operative time, and less blood loss [12]. High rates of non-union can be expected when treating displaced femoral neck fractures, and surgeons who use the FNS device should be aware of the possibility that this device could fail in the manner we describe, should non-union occur, rendering implant removal difficult [34-36]. We recognize that this report describes a single patient experience, which precludes generalizations about overall device reliability, and we do not suggest the FNS is uniquely failure-prone; any device can fail in a non-union under mechanical stress. However, this failure mode presented unusual technical challenges during revision, particularly in comparison to more commonly used constructs, which surgeons should be aware of during surgical planning. The need for trephination to extract the broken antirotation screw and the use of a threaded Steinmann pin to retrieve the broken bolt added complexity and required careful preservation of limited bone stock. These technical demands alone prolonged the surgery by approximately 60 min. The resulting bone loss and surgical burden underscore the importance of considering potential revision implications during implant selection, especially in fractures with relatively high complication rates, such as displaced femoral neck fractures. This consideration is particularly salient in young, active patients, where implant durability, the demands of high-impact activity, and the feasibility of future revisions are critical concerns. Studies have highlighted that younger patients with femoral neck fractures face a unique treatment dilemma—balancing the need for stable fixation against the long-term risk of mechanical failure and reoperation, including conversion to arthroplasty [37,38]. Beyond technical complexity, revision procedures following femoral neck implant failure can impose substantial healthcare and societal costs. Studies have shown that revision surgery after failed internal fixation is associated with significantly higher overall costs and resource utilization compared to primary fixation or arthroplasty [39]. While we did not quantify cost in this case, the surgical demands and resource intensity of osteotomy and blade plate fixation underscore the importance of pre-operative planning and appropriate implant selection to minimize the risk and burden of revision. In addition, while our patient achieved a full return to activity, we did not obtain standardized functional outcome scores, such as the Harris hip score or SF-36 during follow-up. Incorporating validated outcome measures in future case reports and studies would strengthen objective assessments of recovery.

We present a case of FNS failure involving both an antirotation screw and a bolt at the plate barrel aperture in a young patient with non-union. Revision required extensive effort and sacrifice of bone stock. As the FNS is a relatively new implant for treating femoral neck fractures, orthopedic surgeons should be aware of this failure mode and the associated challenges during revision. While our patient demonstrated a full functional recovery with over 18 months of follow-up, describing this mode of failure may inform manufacturers and surgeons of potential failure during implant design or selection and serve as a basis for future comparative studies in this population.

While the FNS offers theoretical advantages in femoral neck fracture fixation, rare failure at the junction of the antirotation screw and bolt near the plate barrel can significantly complicate revision surgery. This case emphasizes the need for careful implant selection, especially in young patients at risk for non-union, and highlights the importance of pre-operative planning for potential implant removal. Recognizing and reporting such failures can guide future design improvements and surgical decision-making.

References

- 1.Robinson CM, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Christie J. Hip fractures in adults younger than 50 years of age. Epidemiology and results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995;312:238-46. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Collinge CA, Finlay A, Rodriguez-Buitrago A, Beltran MJ, Mitchell PM, Mir HR, et al. Treatment failure in femoral neck fractures in adults less than 50 years of age: Analysis of 492 patients repaired at 26 north American trauma centers. J Orthop Trauma 2022;36:271. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Pei F, Zhao R, Li F, Chen X, Guo K, Zhu L. Osteonecrosis of femoral head in young patients with femoral neck fracture: A retrospective study of 250 patients followed for average of 7.5 years. J Orthop Surg Res 2020;15:238. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Verettas DA, Galanis B, Kazakos K, Hatziyiannakis A, Kotsios E. Fractures of the proximal part of the femur in patients under 50 years of age. Injury 2002;33:41-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Swiontkowski MF, Winquist RA, Hansen ST. Fractures of the femoral neck in patients between the ages of twelve and forty-nine years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1984;66:837-46. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Slobogean GP, Sprague S, Bzovsky S, Scott T, Thabane L, Heels-Ansdell D, et al. Fixation using alternative implants for the treatment of hip fractures (FAITH-2): The clinical outcomes of a multicenter 2 × 2 factorial randomized controlled pilot trial in young femoral neck fracture patients. J Orthop Trauma 2020;34:524-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Dedrick DK, Mackenzie JR, Burney RE. Complications of femoral neck fracture in young adults. J Trauma 1986;26:932-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Slobogean GP, Sprague SA, Scott T, Bhandari M. Complications following young femoral neck fractures. Injury 2015;46:484-91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Stoffel K, Zderic I, Gras F, Sommer C, Eberli U, Mueller D, et al. Biomechanical evaluation of the femoral neck system in unstable Pauwels III femoral neck fractures: A comparison with the dynamic hip screw and cannulated screws. J Orthop Trauma 2017;31:131-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Wang Z, Yang Y, Feng G, Guo H, Chen Z, Chen Y, et al. Biomechanical comparison of the femoral neck system versus InterTan nail and three cannulated screws for unstable Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture. Biomed Eng OnLine 2022;21:34. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Schopper C, Zderic I, Menze J, Müller D, Rocci M, Knobe M, et al. Higher stability and more predictive fixation with the Femoral Neck System versus Hansson Pins in femoral neck fractures Pauwels II. J Orthop Translat 2020;24:88-95. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Ge Z, Xiong W, Wang D, Tang Y, Fang Q, Wang L, et al. Comparison of femoral neck system vs. dynamic hip system blade for the treatment of femoral neck fracture in young patients: A retrospective study. Front Surg 2023;10:1092786. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Zhuang K, Wu J, Yang Y, Bai T, Li B. Comparison of clinical efficacy between femoral neck system and cannulated screw in Pauwels type III femoral neck fracture: A meta-analysis. J Back Musculoskelet Rehabil 2025;28:71-82. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Júnior MS, da Silva Azevedo FG. Fixation of intracapsular femoral neck fractures: A systematic review study. Int J Orthop Rheumatol 2025;7:13-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Stoffel K, Michelitsch C, Arora R, Babst R, Candrian C, Eickhoff A, et al. Clinical performance of the Femoral Neck System within 1 year in 125 patients with acute femoral neck fractures, a prospective observational case series. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023;143:4155-64. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Zhou Y, Li Z, Lao K, Wang Z, Zhang L, Dai S, et al. Femoral neck system vs. cannulated screws on treating femoral neck fracture: A meta-analysis and system review. Front Surg 2023;10:1224559. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Stegelmann SD, Butler JT, Mathews DJ, Ostlie HC, Boothby BC, Phillips SA. Survivability of the Femoral Neck System for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in adults. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2023;33:2555-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Kenmegne GR, Zou C, Fang Y, He X, Lin Y, Yin Y. Femoral neck fractures in non-geriatric patients: Femoral neck system versus cannulated cancellous screw. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:70. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Schuetze K, Burkhardt J, Pankratz C, Eickhoff A, Boehringer A, Degenhart C, et al. Is new always better: Comparison of the femoral neck system and the dynamic hip screw in the treatment of femoral neck fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2023;143:3155-61. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Tang Y, Zhang Z, Wang L, Xiong W, Fang Q, Wang G. Femoral neck system versus inverted cannulated cancellous screw for the treatment of femoral neck fractures in adults: A preliminary comparative study. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:504. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Hu H, Cheng J, Feng M, Gao Z, Wu J, Lu S. Clinical outcome of femoral neck system versus cannulated compression screws for fixation of femoral neck fracture in younger patients. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:370. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Davidson A, Blum S, Harats E, Kachko E, Essa A, Efraty R, et al. Neck of femur fractures treated with the femoral neck system: Outcomes of one hundred and two patients and literature review. Int Orthop 2022;46:2105-15. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 23.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) Database. Available from: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfmaude/search.cfm [Last accessed 15 Dec 2024]. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 24.Spivak JM, Zuckerman JD, Kummer FJ, Frankel VH. Fatigue failure of the sliding screw in hip fracture fixation: A report of three cases. J Orthop Trauma 1991;5:325-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 25.Zhu J, Deng X, Hu H, Cheng X, Tan Z, Zhang Y. Comparison of the effect of rhombic and inverted triangle configurations of cannulated screws on internal fixation of nondisplaced femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. Orthop Surg 2022;14:720-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 26.Yang JJ, Lin LC, Chao KH, Chuang SY, Wu CW, Yeh TT, et al. Risk factors for nonunion in patients with intracapsular femoral neck fractures treated with three cannulated screws placed in either a triangle or an inverted triangle configuration. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2013;95:61-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 27.Abdallatif AG, Sharma A, Mahmood T, Aslam N. Complications and outcomes of the internal fixation of non-displaced femoral neck fracture in old patients: A two-year follow-up. Cureus 2023;15:e41391. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 28.Krischak G, Beck A, Wachter N, Jakob R, Kinzl L, Suger G. Relevance of primary reduction for the clinical outcome of femoral neck fractures treated with cancellous screws. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2003;123:404-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 29.Acar B, Eren M, Demirci Z, Demirulus KA, Öztürkmen Y. Risk factors associated with femoral neck fracture outcomes in adults: Retrospective clinical study. Istanbul Med J 2022;23:189-93. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 30.Hoshino CM, Christian MW, O’Toole RV, Manson TT. Fixation of displaced femoral neck fractures in young adults: Fixed-angle devices or Pauwel screws? Injury 2016;47:1676-84. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 31.Simpson AH, Varty K, Dodd CA. Sliding hip screws: Modes of failure. Injury 1989;20:227-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 32.Moon JK, Lee JI, Hwang KT, Yang JH, Park YS, Park KC. Biomechanical comparison of the femoral neck system and the dynamic hip screw in basicervical femoral neck fractures. Sci Rep 2022;12:7915. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 33.Zhong Z, Lan X, Xiang Z, Duan X. Femoral neck system and cannulated compression screws in the treatment of non-anatomical reduction Pauwels type-III femoral neck fractures: A finite element analysis. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 2023;108:106060. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 34.Estrada LS, Volgas DA, Stannard JP, Alonso JE. Fixation failure in femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;399:110-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 35.Haidukewych GJ, Rothwell WS, Jacofsky DJ, Torchia ME, Berry DJ. Operative treatment of femoral neck fractures in patients between the ages of fifteen and fifty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:1711-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 36.Parker, MJ, Raghavan R, Gurusamy K. Incidence of fracture-healing complications after femoral neck fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2007;458:175-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 37.Pauyo T, Drager J, Albers A, Harvey EJ. Management of femoral neck fractures in the young patient: A critical analysis review. World J Orthop 2014;5:204. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 38.Ly TV, Swiontkowski MF. Treatment of femoral neck fractures in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:2254-66. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 39.Zielinski SM, Bouwmans CA, Heetveld MJ, Bhandari M, Patka P, Van Lieshout EM, et al. The societal costs of femoral neck fracture patients treated with internal fixation. Osteoporos Int 2014;25:875-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]