Isolated PLC reconstruction with allograft can effectively restore knee stability in combined PLC-PCL injuries when identified early and managed with a case-specific approach

Dr. Nihar Modi, Orthopaedic Surgeon Sona Medical Centre, Jaslok Hospital and Research Centre, Criticare Asia Multispeciality Hospital and Research Centre, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: modi.nihar95@gmail.com

Introduction: Posterolateral corner (PLC) injuries are often associated with cruciate ligament tears. Historically known as the “dark side” of the knee, advancements have greatly improved our understanding of the PLC, offering various management options today.

Case Report: We present the case of a 44-year-old male with a combined PLC and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) Grade 2 injury. He was managed with an isolated PLC reconstruction using an open anatomical Arciero-based technique with a tibialis anterior allograft. At subsequent follow-ups, the patient was shown to have excellent knee functional outcomes, no instability, and ease of performing regular activities, including low to moderate-demand sporting activities.

Conclusion: Effective management of combined PLC and PCL injuries necessitates early identification of the PLC injury and a case-specific management approach, considering factors such as the patient’s condition, surgeon expertise, and graft availability. Allografts are a viable alternative to autografts for PLC reconstruction, offering several advantages over the latter.

Keywords: Posterolateral corner, posterior cruciate ligament, allografts, isolated posterolateral corner reconstruction, arciero technique, three window technique, multiligament knee injuries.

Historically, the posterolateral corner (PLC) of the knee was known as the “dark side” of the knee because of the limited understanding of its anatomy and biomechanics, as well as the scarcity of treatment options [1,2]. However, over the years, advances have led to a good understanding of this complex injury with biomechanically validated surgical techniques [2,3]. PLC injuries usually occur concomitantly with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tears [2]. Isolated PLC injuries are relatively less common and make up 28% of the total PLC injuries [4,5]. The PLC and cruciates act as restraints to varus stress and external rotation [4]. Failure to recognize and treat PLC injuries can jeopardize the concurrent cruciate ligament reconstructions [6]. In the long run, it can lead to meniscal injuries and accelerated early degeneration of the medial compartment of the knee [7]. Various surgical techniques have been listed over the years, which include the open techniques, arthroscopic-assisted, along with attempts at an all-arthroscopic method using cadavers [3,8-10]. Regarding graft options for PLC reconstruction, the literature talks about both autografts and allografts, with no definitive evidence showing that one is superior to the other [11]. We present the case of a PLC-PCL injury where only the PLC was addressed with an Arciero-based reconstruction using a frozen irradiated tibialis anterior allograft, with a good outcome. Informed consent was obtained from the patient regarding data submission for research and publication.

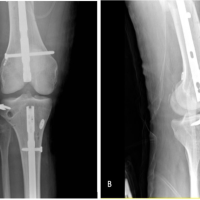

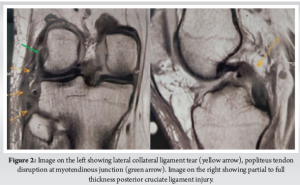

A 44-year-old surgeon presented to us with complaints of right knee pain and instability. He had an anteromedial blow to his right knee after slipping from an elevated platform while he was operating, 4 weeks back. He had no medical comorbidities and was unable to carry out his activities of daily life. On physical examination, the right knee exhibited a positive Grade 2 posterior drawer test along with a dial test showing external rotation asymmetry at 30° as well as at 90° (Fig. 1). There was Grade 3 lateral opening on varus stress and the common peroneal nerve (CPN) examination was unremarkable. Bilateral varus stress radiographs of the knee showed a side-to-side difference of more than 4 mm (Fig. 1). A bilateral lower limb scanogram showed no alignment issues, whereas the magnetic resonance imaging showed a lateral collateral ligament (LCL) tear at the fibular attachment with 1.4 cm retraction and popliteal tendon disruption at the myotendinous junction. PCL showed a partial to full-thickness tear in the midsubstance (Fig. 2). After a thorough evaluation of the physical and radiographic examination, and considering the age and active lifestyle of the patient, we decided on an Arciero-based PLC ligament reconstruction using tibialis anterior allograft. The surgery was performed according to Arciero’s “3-window technique” with a few modifications. A hockey stick incision was made, extending from the distal femoral shaft along the iliotibial band (ITB) proximally, and continuing distally between Gerdy’s tubercle and the fibular head. The third window was created first, inferior to the biceps femoris, where the CPN was identified, protected and exposed distally up to the fibula head. The second window was made between the anterior border of the biceps femoris and the posterior border of the ITB, for future passage of the graft. The first window was then developed by splitting the ITB along its midline and centered over the lateral femoral condyle (Video 1).

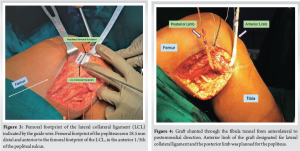

While the exposure was being done by the primary surgeon, the assistant surgeon was simultaneously preparing the allograft. The frozen irradiated tibialis anterior allograft was thawed and prepared (Length: 22 cm, Thickness: 8 mm) by attaching an adjustable loop cortical suspensory fixation implant (FiberTag® TightRope® II) on both sides of the graft. An 8 mm tunnel was made in the fibula from the anterolateral to posteromedial direction, with the tunnel being from inferior to superior. The LCL femoral footprint was identified through the third window, and a guide wire was drilled in the anteromedial direction. 18.5 mm distal and anterior to the LCL footprint, in the anterior 1/5th of the popliteal sulcus, the femoral popliteal tendon insertion was identified (Fig. 3). The abovementioned femur tunnels at the footprints of the LCL and popliteus, respectively, were carefully positioned to avoid tunnel convergence. The next step involved passing the graft through the fibula tunnel from the anterolateral to the posteromedial direction using a shuttling suture. The anterior limb of the graft was designated for insertion at the LCL, whereas the posterior limb was planned for the popliteus (Fig. 4). The anterior limb was passed beneath the ITB and shunted into the LCL tunnel using shuttling sutures, whereas the posterior limb was passed beneath the biceps femoris tendon as well as the ITB (Video 2).

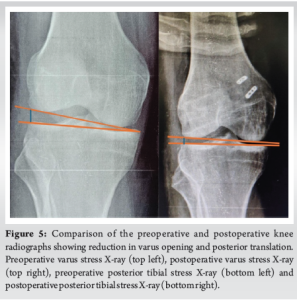

Both limbs were secured in the respective tunnels with the help of an adjustable-loop cortical suspensory fixation implant. Final tensioning was done in a limb position of 30° flexion, slight valgus, and neutral rotation. Final intraoperative stability testing showed reduced lateral opening with varus stress, and the posterior drawer was reduced to Grade 1. Postoperative radiographs showed a reduction in posterior translation and varus opening (Fig. 5). Postoperative rehabilitation involved 6 weeks of non-weight bearing, with range of motion limited to 90° for the first 2 weeks, followed by range of motion as tolerated. The patient began weight-bearing at 6 weeks along with gait training and proprioception exercises. On clinical examination at the 3-month follow-up, external rotation asymmetry was restored to normal, the varus stress test was negative and complete knee range of motion was achieved (Fig. 6). The Posterior drawer test continued to show a Grade 1 laxity, but the patient did not have any instability or symptoms of PCL deficiency. At the 6-month follow-up, the patient was walking pain-free without any limp, had near-normal squatting, and was able to carry out all activities of daily life. At the 1-year follow-up, the Lysholm score was 90/100, the International Knee Documentation Committee (IKDC) score was rank B (near normal), and the patient could comfortably engage in low-to-moderate demand sports [12,13].

The main anatomical principles of PLC reconstruction involve the restoration of the LCL, popliteus tendon and popliteo-fibular ligament (PFL) [14]. The LCL is the primary structure that limits varus stress on the knee, whereas the popliteus tendon helps limit excessive external rotation, and PFL enhances overall knee stability [4]. Overall, the PLC is a restraint to posterior tibial translation on the lateral tibiofemoral compartment, whereas the PCL acts as a similar restraint throughout the range of motion. PLC is the primary restraint to external rotation at lower knee flexion angles, whereas both the PLC and the PCL contribute to controlling external rotation at higher flexion angles (basis of the Dial test) [15]. This mutual relationship justifies the failure of PCL reconstructions in cases where PLC instabilities are unrecognized [15]. According to Harner et al. and Noyes et al., a PLC tear with a PCL Grade 3 injury should be addressed with simultaneous reconstruction of both structures [16,17]. The study by Kim et al. is the only study which has compared isolated PLC reconstruction with simultaneous PLC plus PCL reconstruction, in cases with PLC tears having PCL Grade 2 (or less) injuries [15]. They showed both groups had equally satisfactory postoperative posterolateral stability and no difference in the postoperative symptom scores. However, the study did show that functional outcomes were slightly superior in the simultaneous PLC plus PCL reconstruction group, but less than the minimal clinically important difference [15]. Similarly, in our case, an isolated PLC reconstruction showed good clinical outcomes, allowing the patient to carry out routine activities, including low to medium-demand sports activities. In addition, in our case, the posterior drawer improved from Grade 2 to Grade 1, and no postoperative subjective instability was observed. Hence, when considering treatment of a PLC with PCL (grade 2 or less) injury, it is crucial to take into consideration the patient profile, expectations, and postoperative activity levels, given the disadvantages of additional surgical morbidity, time and cost associated with simultaneous PLC plus PCL reconstructions. The choice of graft in a PLC reconstruction is determined by the type of injury, cost constraints, anthropology and surgeon’s experience [18]. With the advent of tissue banks, various allograft options are available today, along with pre-existing autograft options (Hamstrings, Peroneus longus, patellar tendon) [4]. A meta-analysis by Kern et al., comparing autografts and allografts for PLC reconstruction, found no significant differences in graft failure rates and IKDC scores [11]. A systematic review by Migliorini et al. shows that allografts are a suitable alternative to autografts, with both having equally good functional scores and minimal risk factors [19]. In our case, we chose a tibialis anterior allograft, which gave a satisfactory result and proved to be advantageous in several ways. The allograft ensured a good tendon length and thickness, contributing to optimal strength and shorter operative time, with no donor site morbidity. Precise donor screening, preservation, and optimum sterilization techniques employed by the tissue bank from where it was procured from ensured negligible risk of any graft rejections and adverse outcomes. We utilized an 8 × 22 mm allograft, a size that isn’t achievable with autografts obtained from a single site. The graft’s dimensions facilitated smoother surgery and allowed for easier passage through the tunnels. Stannard et al., in their study, compared outcomes of PLC repair versus PLC reconstruction and found significantly superior outcomes of the latter compared to the former [20]. Various reconstruction techniques have been explored and compared by many authors. Several techniques for PLC reconstruction include the open anatomical approach (such as Larson, Arciero, and LaPrade’s techniques), as well as minimally invasive arthroscopic-assisted and fully arthroscopic methods [8]. We performed a PLC reconstruction using an Arciero-based anatomical technique with a few modifications as described by Grimm et al. [8]. This open anatomical technique has several advantages. The anterolateral to posteromedial trajectory used for the fibular tunnel helps to minimize the risk of CPN palsy as the peroneal nerve courses along the posterolateral neck of the fibula [8]. This fibular tunnel trajectory also helps to recreate the PFL in a better manner. Furthermore, the Arciero technique allows reproduction of the LCL and popliteus origins with the dual femoral tunnel technique [8]. With minimally invasive arthroscopic techniques, the risk of CPN palsy increases significantly [10]. The potential advantages of the Arciero over the Laprade technique include fewer implants, cost, dissection, and overall minimal risk to posterior neurovascular structures, as there are no tibial tunnels involved in the former technique. Considering both techniques are equally effective at restoring knee stability, as shown in the comparative study by Treme et al., the Arciero technique seems to be a more reasonable option for anatomical PLC reconstructions [21]. The management approach in our case also avoided the issue of PLC-PCL femoral tunnel convergence [4]. Had we opted for a combined PLC-PCL reconstruction, it would have required three distal femoral tunnels (two for the PLC and one for the PCL), which could have been a risk factor for compromised bone vascularity [4].

PLC tears are frequently associated with PCL/ACL injuries, and early recognition of the former is very critical in determining the optimum management. Always assess the management of your multi-ligament injuries in light of the patient, surgeon, and graft availability. A well-done anatomical PLC reconstruction can obliviate the need for a PCL reconstruction, with good outcomes, in some cases. With the advent of tissue banks and good tissue banking practices, allografts are now a viable alternative to autografts for PLC reconstructions with several advantages.

- Early identification of PLC injuries is critical, especially when combined with cruciate ligament injuries

- Isolated PLC reconstruction may be sufficient in cases with Grade 2 PCL injuries, avoiding additional surgical morbidity

- Allografts are a viable alternative to autografts, offering benefits like adequate graft size, reduced operative time, and no donor site morbidity

- Surgical approach should be individualized based on patient profile, graft availability, and surgeon expertise.

References

- 1.James EW, LaPrade CM, LaPrade RF. Anatomy and biomechanics of the lateral side of the knee and surgical implications. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2015;23:2-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Chahla J, Moatshe G, Dean CS, LaPrade RF. Posterolateral corner of the knee: Current concepts. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2016;4:97-103. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Ahn JH, Wang JH, Lee SY, Rhyu IJ, Suh DW, Jang KM. Arthroscopic-assisted anatomical reconstruction of the posterolateral corner of the knee joint. Knee 2019;26:1136-42. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Van HN, Manh KN. Concomitantly combined anterior cruciate ligament and posterolateral corner reconstruction: A case report. Int J Surg Open 2023;61:100706. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Geeslin AG, LaPrade RF. Location of bone bruises and other osseous injuries associated with acute grade III isolated and combined posterolateral knee injuries. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:2502-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Ranawat A, Baker CL 3rd, Henry S, Harner CD. Posterolateral corner injury of the knee: Evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2008;16:506-18. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Griffith CJ, Wijdicks CA, Goerke U, Michaeli S, Ellermann J, LaPrade RF. Outcomes of untreated posterolateral knee injuries: An in vivo canine model. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:1192-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Grimm NL, Levy BJ, Jimenez AE, Bell R, Arciero RA. Open anatomic reconstruction of the posterolateral corner: The arciero technique. Arthrosc Tech 2020;9:e1409-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Serra Cruz R, Mitchell JJ, Dean CS, Chahla J, Moatshe G, LaPrade RF. Anatomic posterolateral corner reconstruction. Arthrosc Tech 2016;5:e563-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Liu P, Gong X, Zhang J, Ao Y. Anatomic, all-arthroscopic reconstruction of posterolateral corner of the knee: A cadaveric biomechanical study. Arthroscopy 2020;36:1121-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Kern K, Sanii R, Peterson JC, Menge T. Autograft versus allograft in posterolateral corner reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthop J Sports Med 2024;12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Briggs KK, Lysholm J, Tegner Y, Rodkey WG, Kocher MS, Steadman JR. The reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the lysholm score and tegner activity scale for anterior cruciate ligament injuries of the knee: 25 years later. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:890-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Higgins LD, Taylor MK, Park D, Ghodadra N, Marchant M, Pietrobon R, et al. Reliability and validity of the international knee documentation committee (IKDC) subjective knee form. Joint Bone Spine 2007;74:594-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.LaPrade RF, Wozniczka JK, Stellmaker MP, Wijdicks CA. Analysis of the static function of the popliteus tendon and evaluation of an anatomic reconstruction: The “fifth ligament” of the knee. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:543-9 [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Kim SJ, Lee SK, Kim SH, Kim SH, Jung M. Clinical outcomes for reconstruction of the posterolateral corner and posterior cruciate ligament in injuries with mild grade 2 or less posterior translation: Comparison with isolated posterolateral corner reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2013;41:1613-20. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Harner CD, Vogrin TM, Hoher J, Ma CB, Woo SL. Biomechanical analysis of a posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Deficiency of the posterolateral structures as a cause of graft failure. Am J Sports Med 2000;28:32-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Posterior cruciate ligament revision reconstruction, part 1: Causes of surgical failure in 52 consecutive operations. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:646-54 [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Pache S, Sienra M, Larroque D, Talamás R, Aman ZS, Vilensky E, et al. Anatomic posterolateral corner reconstruction using semitendinosus and gracilis autografts: Surgical technique. Arthrosc Tech 2021;10:e487-97. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Migliorini F, Pintore A, Oliva F, Eschweiler J, Bell A, Maffulli N. Allografts as alternative to autografts in primary posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2023;31:2852-60. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Stannard JP, Brown SL, Farris RC, McGwin G Jr., Volgas DA. The posterolateral corner of the knee: Repair versus reconstruction. Am J Sports Med 2005;33:881-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Treme GP, Salas C, Ortiz G, Gill GK, Johnson PJ, Menzer H, et al. A biomechanical comparison of the arciero and laprade reconstruction for posterolateral corner knee injuries. Orthop J Sports Med 2019;7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]