High-energy periprosthetic fractures around well-fixed unicompartmental knee arthroplasty components can be successfully managed with standard fixation techniques without requiring implant revision.

Dr. Amyn M Rajani, OAKS Clinic, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dramrajani@gmail.com

Introduction: Periprosthetic fractures (PPFs) are well-documented complications after total knee arthroplasty but are exceedingly rare following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA). Given UKA’s design preserves native bone stock and maintains near-normal joint biomechanics, PPFs around well-fixed UKA components are infrequently encountered and poorly described in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, there are very few detailed reports of supracondylar femoral or proximal tibial PPFs following mobile-bearing UKA. This case series is important because it highlights not only the rarity of these injuries but also their successful management without compromising the integrity of the prosthetic components.

Case Report: We present two unique cases of PPFs following cemented mobile-bearing Oxford UKA in elderly South Asian women. The first case involves a 63-year-old woman who sustained a high-energy supracondylar femoral PPF (Unified Classification System Type C) 9 months post-UKA. Despite the severity of the injury, radiographs confirmed the femoral component remained well-fixed with no evidence of polyethylene insert dislocation. She was treated successfully with retrograde intramedullary nailing, achieving full fracture union and 130° of knee flexion by 6 months postoperatively. The second case involves a 60-year-old woman who sustained a proximal third tibial PPF (Type C) two and a half months after UKA. Again, both components remained secure without signs of loosening. She was treated with locking plate fixation, resulting in complete union and full independent ambulation by 6 months. Both patients remained clinically well at 2.5 years of follow-up, with intact UKA components and no functional limitations.

Conclusion: These cases underscore that even severe, high-energy PPFs around UKA can be effectively managed with standard anatomical fixation techniques without necessitating implant revision. The report advances clinical knowledge by demonstrating the structural resilience of well-fixed mobile-bearing UKA components in the setting of traumatic fracture. It is of particular interest to orthopaedic surgeons specializing in arthroplasty and trauma, but also has broader implications for surgical planning, patient counseling, and post-operative expectations.

Keywords: Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty, periprosthetic femoral fracture, Oxford knee, retrograde intramedullary nailing, supracondylar fracture, proximal tibia periprosthetic fracture, locking plate

Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA) has become a well-established surgical option for treating anteromedial osteoarthritis of the knee, with excellent long-term outcomes [1,2]. It is widely regarded as a safe procedure, with low rates of perioperative complications [3]. Common complications associated with UKA include aseptic loosening, polyethylene insert dislocation, unexplained pain, and periprosthetic tibial fractures [2,4]. The incidence of tibial periprosthetic fractures (PPFs) is variably reported ranging between 0.1 and 8% [5]. In contrast, the incidence of supracondylar femoral fractures following total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is reported at 0.5–2% [6,7], but such fractures are exceedingly rare following UKA. To the best of our knowledge, neither a proximal third tibial PPF nor a supracondylar femoral fracture following UKA has previously been documented in the literature. In this case series, we present two patients who sustained post-traumatic, post-operative supracondylar femoral and proximal third tibial fractures, respectively, following primary left-sided UKA.

Case report 1

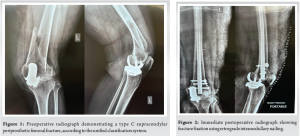

A 63-year-old woman underwent a cemented, mobile-bearing Oxford Phase 3 UKA in 2021, performed by the senior author, for anteromedial osteoarthritis of the left knee. Her post-operative recovery was uneventful. Nine months later, she sustained a high-impact injury in a vehicular accident. Radiographic evaluation revealed a supracondylar, extra-articular periprosthetic femoral fracture, classified as Type C according to the Unified Classification System (UCS) [7] (Fig. 1). There was no evidence of ligamentous instability. Both femoral and tibial components appeared well-fixed, and no polyethylene insert dislocation was observed on imaging.

The patient underwent retrograde intramedullary nailing (RIMN) for fracture fixation (Fig. 2). Her pre-injury Oxford Knee Score (OKS) was 48. Following fracture healing, her OKS decreased to 40. Active and passive range-of-motion exercises were initiated immediately after surgery. At 12 weeks postoperatively, radiographs confirmed fracture union, and full weight-bearing ambulation was permitted. By 5 months postoperatively, the patient had regained a full range of motion (130°), was able to sit cross-legged, and walked independently (Fig. 3 and 4). At 2½ years after fracture fixation, the UKA components remained well-fixed, and the patient’s OKS was 32 (Fig. 5).

Case report 2

A 60-year-old woman presented with left knee pain for over 6 months. Radiographs showed anteromedial osteoarthritis with underlying osteoporosis. A mobile bearing left UKA was performed in September 2022. Her post-operative recovery was uneventful.

Two and a half months post-UKA, in December 2022, she was involved in a high-velocity road traffic accident. Radiographs revealed a proximal third tibial shaft PPF, classified as Type C according to the UCS. There was no evidence of ligamentous laxity. Both UKA components were well-fixed, and no insert dislocation was observed radiographically. The patient underwent internal fixation with a proximal tibial plate. Intraoperatively, the fracture line was found approximately 5 cm below the tibial component. Through an anterolateral approach, a long lateral anatomical plate was applied and fixed with locking screws. Her pre-injury OKS was 46. Following fixation, it decreased to 32. Active-assisted and passive knee range-of-motion exercises were initiated immediately. At 14 weeks postoperatively, radiographs and computed tomography scans demonstrated good fracture union (Fig. 6), and full weight-bearing was permitted. Her OKS had improved to 38.

By 6 months, she had regained full range of motion (130°), could sit cross-legged, and walked independently without aids (Fig. 7 and 8). At 2 years and 8 months from the primary UKA (2 years and 5 months post-fracture fixation), the UKA components remained well-fixed, and her OKS was 46 (Fig. 9).

This case series highlights that Oxford UKA components can remain stable and intact even following significant trauma resulting in supracondylar femoral and proximal third tibial PPFs. Both patients demonstrated successful fracture healing without complications and regained near-complete knee function. Despite an extensive literature review, we found no previously reported cases describing either supracondylar femoral or proximal third tibial PPFs following Oxford UKA. Several studies have identified anatomical differences in Asian versus Caucasian knee morphology that may increase the risk of PPF [8-10]. Anthropometric research has demonstrated that the Asian tibial metaphysis is generally smaller and narrower, with a higher prevalence of tibial vara [11-13]. These anatomical characteristics predispose to a medially overhanging tibial condyle, as described by Yoshikawa et al. using the extramedullary medial tibial eminence line. This feature has been associated with an increased risk of PPF [8,11]. PPFs following UKA most commonly occur within the first 3 months postoperatively [14,15]. Patient-specific factors such as age, female sex, reduced bone mineral density, low bone mineral content, and smaller tibial morphology have also been implicated as risk factors [16]. Both advanced age and female sex are closely linked with osteoporosis, which not only predisposes patients to fractures but also significantly complicates management due to impaired healing potential and increased surgical difficulty [17-19]. Moreover, osteoporosis has been associated with higher morbidity and mortality when involved in PPFs, particularly due to challenges in fixation and bone healing [20]. The primary objectives in managing such injuries are to restore axial alignment, maintain limb length, and achieve mechanical stability to enable early mobilization. These goals can be difficult to attain in elderly patients with osteoporotic bone, where the risk of non-union is substantial. Non-union rates following PPFs after TKA have been reported to range from 0% to 50% [21]. Preservation of soft-tissue integrity and fracture fragment vascularity is essential in minimizing this risk. Achieving correct axial alignment was particularly important in our cases, as UKA components may be less tolerant to malalignment compared to TKA prostheses, particularly due to increased susceptibility to shear forces [22]. Therefore, fracture location and displacement play critical roles in determining the surgical approach. Common surgical options for managing displaced supracondylar periprosthetic femoral fractures include locking plate fixation and RIMN. Locking plates are preferred when the fracture is located in the cancellous portion of the distal femur, as they provide precise anatomical reconstruction [23,24]. In our first patient, RIMN was a viable option due to the UKA design, which preserves the femoral notch and allows access to the intramedullary canal. However, for low supracondylar fractures, locked plating may be more appropriate due to technical challenges in achieving stable distal fixation with nails and the risk of varus malalignment or collapse [25]. For proximal third tibial fractures, the preferred treatment is internal fixation using locking plates. In our second patient, a lateral anatomical locking plate was applied through the anterolateral approach, with careful attention to preserving the integrity of the UKA components and polyethylene insert, which remained well-seated. Polyethylene insert dislocation is a recognized complication of mobile-bearing UKA, commonly resulting from ligament imbalance or malpositioned components [26]. Despite the high-energy trauma in both cases, insert dislocation was not observed, likely due to precise surgical technique and effective ligament balancing at the time of primary UKA. We hypothesize that a well-executed mobile-bearing UKA transmits predominantly compressive forces across the implant-bone interface, reducing shear and tensile stresses. This favorable biomechanical profile may contribute to the stability of the implant under traumatic loading, potentially explaining the absence of component loosening in both cases. While various classification systems exist for PPFs after TKA, none are specifically designed for UKA-related injuries [27]. This likely reflects the much lower incidence of such fractures in UKA. The UCS, adapted from the Vancouver classification, appears to be the most appropriate and inclusive for categorizing these injuries [7,28]. In our series, both fractures were classified as Type C—fractures remote from the prosthesis. According to UCS guidelines, such fractures can typically be managed with internal fixation without compromising the implant [29,30].

This case series demonstrates that a well-executed, well-balanced Oxford UKA can withstand high-energy trauma without resulting in polyethylene insert dislocation or component loosening. Furthermore, bone healing can proceed rapidly and uneventfully with appropriate management. In such rare PPFs, the primary surgical goals should focus on restoring mechanical alignment and achieving near-anatomical reduction to facilitate early mobilization and optimize functional outcomes.

In cases of PPFs following UKA, careful assessment of implant stability allows for effective management with conventional fracture fixation, preserving the existing prosthesis and ensuring excellent functional recovery.

References

- 1. Pandit H, Jenkins C, Gill HS, Barker K, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Minimally invasive oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee replacement: Results of 1000 cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:198-204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Price AJ, Waite JC, Svard U. Long-term clinical results of the medial oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;435:171-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Morris MJ, Molli RG, Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr. Mortality and perioperative complications after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Knee 2013;20:218-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Vince KG, Cyran LT. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: New indications, more complications? J Arthroplasty 2004;19:9-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Liddle AD, Judge A, Pandit H, Murray DW. Adverse outcomes after total and unicompartmental knee replacement in 101,330 matched patients: A study of data from the national joint registry for England and Wales. Lancet 2014;384:1437-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Ayers DC, Dennis DA, Johanson NA, Pellegrini JV. Instructional course lectures, the American academy of orthopaedic surgeons-common complications of total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1997;79:278-311. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Meek RM, Norwood T, Smith R, Brenkel IJ, Howie CR. The risk of peri-prosthetic fracture after primary and revision total hip and knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:96-101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Hiranaka T, Yoshikawa R, Yoshida K, Michishita K, Nishimura T, Nitta S, et al. Tibial shape and size predicts the risk of tibial plateau fracture after cementless unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in Japanese patients. Bone Joint J 2020;102-B:861-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Yoshida K, Tada M, Yoshida H, Takei S, Fukuoka S, Nakamura H. Oxford phase 3 unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in Japan–clinical results in greater than one thousand cases over ten years. J Arthroplasty 2013;28:168-17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Xian LZ, Tan AH. An early periprosthetic fracture of a cementless Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: Risk factors and mitigation strategies. J Orthop Case Rep 2021;11:65-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Yoshikawa R, Hiranaka T, Okamoto K, Fujishiro T, Hida Y, Kamenaga T, et al. The medial eminence line for predicting tibial fracture risk after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Surg 2020;12:166-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Yue B, Varadarajan KM, Ai S, Tang T, Rubash HE, Li G. Differences of knee anthropometry between Chinese and white men and women. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:124-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Burger JA, Jager T, Dooley MS, Zuiderbaan HA, Kerkhoffs GM, Pearle AD. Comparable incidence of periprosthetic tibial fractures in cementless and cemented unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022;30:852-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Mohammad HR, Barker K, Judge A, Murray DW. A comparison of the periprosthetic fracture rate of unicompartmental and total knee replacements: An analysis of data of >100,000 knee replacements from the national joint registry for England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of man and hospital episode statistics. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2023;105:1857-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Thoreau L, Marfil DM, Thienpont E. Periprosthetic fractures after medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A narrative review. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2022;142:2039-48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Porter JL, Varacallo MA. Osteoporosis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Aspray TJ, Hill TR. Osteoporosis and the ageing skeleton. Subcell Biochem 2019;91:453-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Bonnick SL. Osteoporosis in men and women. Clin Cornerstone 2006;8:28-39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Binkley N, Nickel B, Anderson PA. Periprosthetic fractures: An unrecognized osteoporosis crisis. Osteoporos Int 2023;34:1055-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Duncan CP, Haddad FS. The unified classification system (UCS): Improving our understanding of periprosthetic fractures. Bone Joint J 2014;96-B:713-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Hoffmann MF, Jones CB, Sietsema DL, Koenig SJ, Tornetta P 3rd. Outcome of periprosthetic distal femoral fractures following knee arthroplasty. Injury 2012;43:1084-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Karagüven D, Yildirim T, Akan B, Doral MN. Supracondylar extra-articular femur fracture after cementless unicompartmental knee replacement: A rare complication. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2022;28:1754-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Herrera DA, Kregor PJ, Cole PA, Levy BA, Jönsson A, Zlowodzki M. Treatment of acute distal femur fractures above a total knee arthroplasty: Systematic review of 415 cases (1981-2006). Acta Orthop 2008;79:22-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Desouza C, Antao N, Londhe S, Banka P. Long-term functional outcomes of BIFOLD osteosynthesis in distal femoral fractures with metaphyseal comminution: A retrospective analysis. J Orthop 2024;63:16-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Chettiar K, Jackson MP, Brewin J, Dass D, Butler-Manuel PA. Supracondylar periprosthetic femoral fractures following total knee arthroplasty: Treatment with a retrograde intramedullary nail. Int Orthop 2009;33:981-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Matlovich NF, Lanting BA, Vasarhelyi EM, Naudie DD, McCalden RW, Howard JL. Outcomes of surgical management of supracondylar periprosthetic femur fractures. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:189-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Li B, Gao P, Qiu G, Li T. Locked plate versus retrograde intramedullary nail for periprosthetic femur fractures above total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Int Orthop 2016;40:1689-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Jeong JH, Kang H, Ha YC, Jang EC. Incarceration of a dislocated mobile bearing to the popliteal fossa after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2012;27:323.e5-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Rorabeck CH, Taylor JW. Classification of periprosthetic fractures complicating total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Clin North Am 1999;30:209-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Konan S, Sandiford N, Unno F, Masri BS, Garbuz DS, Duncan CP. Periprosthetic fractures associated with total knee arthroplasty: An update. Bone Joint J 2016;98-B:1489-96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]