It's important to note that while biomarkers are valuable diagnostically, they should be used in conjunction with other clinical assessments and diagnostic tools, such as imaging studies and the probe-to-bone test, to ensure accurate diagnosis and effective management of diabetic foot osteomyelitis.

Dr Mantu Jain, Department of Orthopaedic, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: montu_jn@yahoo.com

Introduction: Foot ulcer is one of the common problems in patients with diabetes mellitus. The spectrum of diabetic foot infection is wide, ranging from cellulitis and soft tissue infection to osteomyelitis (OM). OM requires further testing and investigations and even longer treatments. The aim of this prospective study was to assess the performance of serum markers, namely, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), and procalcitonin (PCT) in the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with diabetic foot osteomyelitis (DFO) and to find correlation between serum levels of these biomarkers and treatment response.

Materials and Methods: This prospective study was carried out in 50 patients. Diagnosis of OM was made by clinical examination and confirmed by radiological studies. The serum levels of ESR, CRP, and PCT were determined on admission in all the patients and then on day 15 and day 30 in the osteomyelitic group.

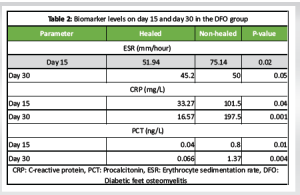

Results: No significant difference was observed in the levels of ESR, CRP, and PCT in DFO and non-OM patients (P > 0.05) at presentation. However, there was a significant difference (P > 0.05) in levels of these markers between patients with healed and non-healed lesions in the osteomyelitic group on day 15 and day 30.

Conclusion: Biomarkers may not help in diagnosing OM. However, the level of biomarkers decreases significantly in response to treatment validating their role in predicting healing.

Keywords: Biomarkers, diabetic foot, osteomyelitis, procalcitonin.

Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common metabolic diseases worldwide. Diabetic foot complications are a serious condition in patients with long-term diabetes [1]. Each year, approximately 5% of all diabetics develop foot ulcers, with up to 60% of all foot ulcers being infected at the time of presentation [2]. Failure to detect local wound infection in diabetic patients leads to the involvement of deeper structures [3]. Chronic and deep wounds are exacerbated by osteomyelitis (OM), which is found in 20% of mild to moderate infections and 50–60% of severely infected wounds [4]. Winkler estimates that approximately 28% of patients with OM require amputation [5]. As a result, early detection is critical, as a delay in diagnosis or inadequate treatment can result in limb loss or death [4]. The diagnosis of OM in patients with foot ulcers is primarily based on clinical examination and imaging studies, but both have limitations. Recently, several studies have investigated the role of biomarkers such as procalcitonin (PCT), C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and others in distinguishing bacterial infections from non-bacterial infections, monitoring treatment response, and predicting outcome in systemic infections [6,7]. There is very little information available about the role of these biomarkers in diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis (DFO). Apart from diagnosis, monitoring response to treatment is an important issue in OM because it determines future management and helps to avoid overtreatment. There are currently no guidelines for following up with patients who have DFO. The present study was therefore planned to examine the performance of serum inflammatory markers – ESR, CRP, and PCT in diagnosing OM in patients with diabetic foot ulcers (DFU) and to assess the change in these levels in response to treatment.

This prospective study was conducted over a 2-year period at a tertiary care center in Northern India, following the Institute’s ethical approval. Our study included fifty outpatients who visited a diabetic foot clinic or were admitted to our hospital with diabetic foot complications (Fig. 1). Patients over the age of 30 with known diabetes, DFU disease, and moderately or severely infected wounds (as classified by the combined Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) and International Working Group on Diabetic Foot) were included in the study. Patients with severe sepsis and a history of concomitant conditions (venous ulcer/Burgers disease) that could cause ulcers, as well as those with systemic inflammatory diseases (rheumatoid arthritis), which can affect serum inflammatory marker levels, were excluded from the study.

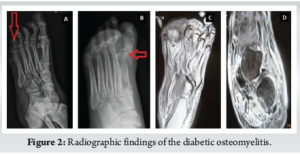

All patients had undergone a thorough clinical assessment. DFO was diagnosed based on at least one clinical feature, such as a positive probe-to-bone test, visible bone at the ulcer base, or at least one of the following supportive radiographic features on a plain radiograph: Periosteal reaction, loss of trabecular architecture, endosteal scalloping, bone destruction, or sequestered bone [8]. To confirm OM in patients with a doubtful diagnosis on plain X-ray, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed (Fig. 2). The presence of periosteal reaction, sequestrum, and a characteristic alteration in bone marrow signal intensity on MRI led to the diagnosis of OM [9]. ESR, CRP, and PCT levels were compared in the osteomyelitic and non-osteomyelitic groups at 0, 15, and 30 days of treatment.

The end of an OM episode was defined as wound healing with no clinical or radiological signs of infection, or the point at which antibiotics were discontinued. The endpoint for those who had an amputation was discharge after the procedure (Fig. 3 & 4). The data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software. Quantitative data were presented as mean, standard deviation or median with interquartile range, as appropriate. For normally distributed data, the mean was compared using the impaired t-test. For skewed data or scores, the Mann–Whitney test will be used. For categorical variables, both numbers and percentages were calculated. Categorical data were analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

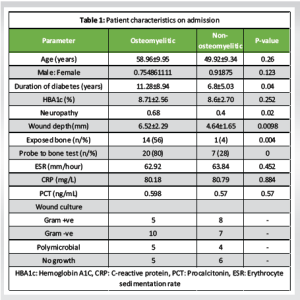

Patients were divided into two groups: Osteomyelitic and non-osteomyelitic, each with 25 patients. Table 1 depicts demographic details. Patients included in the study did not differ in terms of age, gender, or hemoglobin A1C status. Patients with OM had a longer disease duration and neuropathy. Patients with deep wounds, exposed bone, and a positive probe-to-bone test had a higher risk of OM. Imaging confirmed a false positive rate of 7/25 (28%) for the probe to bone test. There was no significant difference in the distribution of microorganisms between the two groups during presentation. The baseline values of ESR, CRP, and PCT at presentation (Day 0) were evaluated and found to be statistically insignificant (Table 1). DFO patients were followed on days 15 and 30 to assess biomarker levels. These patients were further divided into two groups: Healing and non-healing, and biomarker levels were measured on Days 15 and 30 of presentation. On day 15, there were 18 patients in the healing group, followed by 19 on day 30. Table 2 shows that the mean values of ESR, CRP, and PCT were statistically significant in healed wounds when compared to non-healing patients on days 15 and 30. During follow-up, the absolute levels of inflammatory markers decreased in response to therapy.

DFU has a significant health and socioeconomic impact on the quality of life of patient [10]. Chronic wounds are usually complicated by OM. Presence of OM delays wound healing, requires a longer duration of antibiotic therapy, and longer duration of hospital stay, thus increasing treatment cost [10]. Furthermore, the risk of amputation increases by 4 times in the presence of OM as compared to soft tissue infection [11]. Therefore, early diagnosis as well as treatment is required for OM in diabetic foot patients [12]. Various risk factors have been found to be associated with OM. Apart from vasculopathy and neuropathy, wound depth is associated with a significant risk of OM [13]. In our study, neuropathy and vasculopathy were more common in the osteomyelitic group (P = 0.02). The mean depth of wound in the present study, in the osteomyelitic group, was 6.52 ± 2.29 mm, which was significantly more than the depth of wound in non-osteomyelitic group (4.64 ± 1.65 m) with P = 0.0098. Giurato et al., emphasized that DFO was more common in deeper ulcers (>3 mm) as compared to superficial ulcers [14]. Exposed bone is another factor that increases the chances of bone infection [14]. Exposed bone provides direct contact with microorganisms, leading to contagious bone involvement and OM. Malhotra et al. also observed that the presence of clinically visible bone is a predictor for the presence of OM [15]. The diagnosis of DFO is usually difficult, especially in the early stage. A combination of clinical findings, along with microbiological and imaging studies, is recommended to diagnose DFO. Probe to bone test is considered as one of the reliable clinical tests to diagnose OM with reported sensitivity and specificity is 98% and 79%, respectively [8]. In the present study, it also turned out to be a false positive in 7 (28%) of the patients. Lavery et al. evaluated 1666 diabetic patients and found that the probe to bone test had a positive predictive value of 0.57, but the negative predictive value approached 0.98 [16]. Based on these results, it was concluded that diagnosis of OM should not be made entirely with the probe to bone test. The sensitivity of X-ray films in diagnosing OM has shown variable results. It is related to chronicity of infection and at least 30–50% bone loss is required to show changes on plain radiograph and such changes take at least 2–3 weeks to manifest [17]. We also observed that X-ray was positive in 11 individuals with a sensitivity of 44% and cannot be relied upon as the sole imaging technique for diagnosing OM. Other imaging studies that can be used for the diagnosis of DFO are MRI, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (CT) with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose, 99mTc white blood cell-labeled single-photon emission CT and CT [18]. However, they have their own limitations. In this prospective study of 50 individuals suffering from DFUs, we explored the diagnostic and prognostic accuracy of three specific inflammatory markers-ESR, CRP, and PCT in OM. Our results showed that, at the outset, there were no meaningful differences in these markers between patients with DFO and those without OM (P > 0.05). However, for those with DFO who began to heal, there was a clear drop in ESR, CRP, and PCT levels by days 15 and 30 of treatment, suggesting these markers could be helpful in tracking treatment outcomes and forecasting recovery. In the study by Xu et al., although CRP levels differed between the two groups, its diagnostic performance was limited, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.697 [19]. In contrast, ESR demonstrated a significantly higher AUC of 0.832, indicating its superior utility as a serum biomarker for diagnosing DFO. Soleimani et al. reported that inflammatory markers, including ESR and CRP, were elevated in patients with diabetic foot infections, with higher levels in those with underlying OM [20]. Despite this elevation, the diagnostic accuracy was limited-ESR demonstrated only fair accuracy, while CRP showed poor discriminatory ability in identifying OM among these patients. Hadavand et al. observed that patients diagnosed with OM showed significantly elevated levels of PCT, ESR, and CRP compared to those without [21]. The optimal cutoff values identified for predicting OM were 0.35 ng/mL for PCT (with 86.1% sensitivity and 45.3% specificity), 56.5 mm/h for ESR (95.8% sensitivity, 50.0% specificity), and 44 mg/mL for CRP (90.3% sensitivity, 57.0% specificity). These findings highlight that while these markers are sensitive in detecting OM, their specificity remains modest, limiting their utility as standalone diagnostic tools. Lavery et al. identified an ESR threshold of 60 mm/h and a CRP level of 7.9 mg/dL as optimal cut-off points for predicting OM [22]. Their findings suggest that ESR is more effective for initially ruling out OM, whereas CRP serves as a useful marker to differentiate OM from soft tissue infections, particularly in patients presenting with elevated ESR levels. Despite these insights, our research didn’t find notable differences in initial biomarker levels between those with and without DFO. Differences in how studies were set up, the patient groups involved, and how DFO was diagnosed may explain these inconsistencies. Even though ESR, CRP, and PCT might not be strong standalone tools for diagnosing DFO, their noticeable drop in patients who respond to treatment suggests they can be useful in tracking disease progression and gauging treatment success. Regular testing of these biomarkers could help guide clinical decisions. Crisologo et al. studied the role of serum biomarkers to monitor high-risk patients for reinfection of bone in diabetic patients [23]. Elevated ESR, CRP, interleukin-6 (IL-6), and IL-8, along with reduced monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 after 6 weeks of therapy, were linked to the development of OM. Marios et al. showed that decreases in these markers are linked with patients getting better, reinforcing their value for monitoring treatment [24]. Similarly, Todorova’s study found that PCT and highly sensitive CRP levels dropped significantly in patients who responded to therapy, underlining their promise in evaluating how effective treatment is [25]. This aligns with recommendations from the IDSA, which advises using these blood markers when clinical signs aren’t clear [26]. As cost-effective and accessible tools, biomarkers can be monitored every 3–4 weeks to detect emerging or recurrent OM, guiding timely imaging, biopsy, or treatment adjustments. These markers can be particularly helpful in places without access to advanced imaging technology. In such cases, regularly checking ESR, CRP, and PCT could provide essential information on how a patient is responding to treatment, helping to guide timely decisions and possibly improve outcomes.

Limitations

The sample size was relatively small, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. In addition, we did not account for potential confounding factors, such as renal function, which can influence biomarker levels. Future studies with larger cohorts and consideration of comorbidities are warranted to validate and expand upon our findings.

Going by the encouraging results of the biomarkers in our study, we recommend the use of biomarkers in predicting healing in patients with OM. This will prevent unnecessary and overuse of antibiotics and further decrease the health burden on the healthcare system.

The limited diagnostic utility of ESR, CRP, and PCT at baseline emphasizes the need for a multifaceted approach to diagnosing DFO, incorporating clinical assessment, imaging, and possibly other biomarkers. Nevertheless, the close relationship between healing and decreasing biomarker levels means sequential measurement might be useful in directing treatment and providing predictive information. Monitoring these biomarkers over time may help clinicians assess response to therapy and adjust management strategies accordingly.

References

- 1. Shaw JE, Sicree RA, Zimmet PZ. Global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2010 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2010;87:4-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Prompers L, Huijberts M, Apelqvist J, Jude E, Piaggesi A, Bakker K, et al. Optimal organization of health care in diabetic foot disease: Introduction to the Eurodiale study. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2007;6:11-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Nubé V, Bolton T, Chua E, Yue D. Osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot: What lies beneath. Primary Intention 2007;15:49-57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Lipsky BA. A report from the international consensus on diagnosing and treating the infected diabetic foot. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2004;20 Suppl 1:S68-77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Winkler E, Schöni M, Krähenbühl N, Uçkay I, Waibel FW. Foot osteomyelitis location and rates of primary or secondary major amputations in patients with diabetes. Foot Ankle Int 2022;43:957-67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Cho H, Lee JH, Park SC, Lee SJ, Youk HJ, Nam SJ, et al. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as diagnostic biomarkers for bacterial gastroenteritis: A retrospective analysis. J Clin Med 2025;14:2135. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Nargis W, Ibrahim M, Ahamed BU. Procalcitonin versus C-reactive protein: Usefulness as biomarker of sepsis in ICU patient. Int J Crit Illn Inj Sci 2014;4:195-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Morales Lozano R, Gonzalez Fernandez ML, Martinez Hernandez D, Beneit Montesinos JV, Guisado Jimenez S, Gonzalez Jurado MA. Validating the probe-to-bone test and other tests for diagnosing chronic osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Diabetes Care 2010;33:2140-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Dobaria DG, Cohen HL. Osteomyelitis imaging. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594242 [Last accessed on 2023 Aug 06]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Bodhare T, Bele S, Balakumaran B, Ramji M, Francis JG, Shalini V, et al. Health costs and quality of life among diabetic foot ulcer patients in South India: A cross-sectional study. Cureus 2025;17:e79950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Johnson MJ, Shumway N, Bivins M, Bessesen MT. Outcomes of limb-sparing surgery for osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot: Importance of the histopathologic margin. Open Forum Infect Dis 2019;6:ofz382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Lipsky BA, Moran GJ, Napolitano LM, Lien V, Nicholson S, Kim M. A prospective, multicenter, observational study of complicated skin and soft tissue infections in hospitalized patients: Clinical characteristics, medical treatment, and outcomes. BMC Infect Dis 2012;12:227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Momodu II, Savaliya V. Osteomyelitis. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk532250. [Last accessed on 2025 March 9 ] [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Giurato L, Meloni M, Izzo V, Uccioli L. Osteomyelitis in diabetic foot: A comprehensive overview. World J Diabetes 2017;8:135¬42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Malhotra R, Chan CS, Nather A. Osteomyelitis in the diabetic foot. Diabet Foot Ankle. 2014;5:10.3402/dfa.v5.24445. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 16. Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Peters EJ, Lipsky BA. Probe-to-bone test for diagnosing diabetic foot osteomyelitis: Reliable or relic? Diabetes Care 2007;30:270-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Harmer JL, Pickard J, Stinchcombe SJ. The role of diagnostic imaging in the evaluation of suspected osteomyelitis in the foot: A critical review. Foot (Edinb) 2011;21:149-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Lauri C, Noriega-Álvarez E, Chakravartty RM, Gheysens O, Glaudemans AW, Slart RH, et al. Diagnostic imaging of the diabetic foot: An EANM evidence-based guidance. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2024;51:2229-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Xu J, Cheng F, Li Y, Zhang J, Feng S, Wang P. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate combined with the probe-to-bone test for fast and early diagnosis of diabetic foot osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2021;20:227-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Soleimani Z, Amighi F, Vakili Z, Momen-Heravi M, Moravveji SA. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), quantitative C-reactive protein (CRP) and clinical findings associated with osteomyelitis in patients with diabetic foot. Hum Antibodies 2021;29:115-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Hadavand F, Amouzegar A, Amid H. Pro-calcitonin, erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C – reactive protein in predicting diabetic foot ulcer characteristics; a cross sectional study. Arch Acad Emerg Med 2019;7:37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Lavery LA, Ahn J, Ryan EC, Bhavan K, Oz OK, La Fontaine J, et al. What are the optimal cutoff values for ESR and CRP to diagnose osteomyelitis in patients with diabetes-related foot infections? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2019;477:1594-602. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Crisologo PA, Davis KE, Ahn J, Farrar D, Van Asten S, La Fontaine J, et al. The infected diabetic foot: Can serum biomarkers predict osteomyelitis after hospital discharge for diabetic foot infections? Wound Repair Regen 2020;28:617-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Marios M, Jude E, Christos L, Spyridon K, Konstantinos M, Dimitrios D, et al. The performance of serum inflammatory markers for the diagnosis and follow-up of patients with osteomyelitis. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2013;12:94-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Todorova AS, Jude EB, Dimova RB, Chakarova NY, Serdarova MS, Grozeva GG, et al. Vitamin D status in a bulgarian population with type 2 diabetes and diabetic foot ulcers. Int J Low Extrem Wounds 2022;21:506-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Ansert EA, Tarricone AN, Coye TL, Crisologo PA, Truong D, Suludere MA, et al. Update of biomarkers to diagnose diabetic foot osteomyelitis: A meta-analysis and systematic review. Wound Repair Regen 2024;32:366-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]