Bilateral distal femoral fractures in paraplegic patients present unique challenges due to underlying osteoporosis and altered healing capacity.

Dr. Brendan J Liakos, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, VCME Orthopedic Surgery Residency, Modesto, California. E-mail: brendanjliakos@gmail.com

Introduction: Lower extremity fractures are a frequent complication in patients with chronic spinal cord injury due to significant bone mineral density loss and altered bone metabolism. While non-operative management has traditionally been favored, advances in surgical techniques have expanded treatment options, including intramedullary nailing and plate fixation. However, the optimal approach remains controversial, especially in paraplegic patients with distal femoral fractures. This case report highlights the challenges and complications associated with surgical management in this unique patient population

Case Report: A 45-year-old male with T2 paraplegia presented with bilateral distal femoral shaft fractures following a motor vehicle accident. He underwent bilateral retrograde intramedullary nailing to preserve mobility and independence. Postoperatively, the patient developed a hypertrophic non-union on the right side with hardware migration, requiring revision with plate and screw fixation. Subsequently, he developed painful hardware on the right and severe heterotopic ossification on the left, significantly impacting his quality of life. Although hardware removal was recommended, the surgeries were never performed due to the patient’s clinical course and eventual death from unrelated causes.

Conclusion: Clinicians should be aware of the potential complications associated with intramedullary nailing and revision open reduction internal fixation in paraplegic patients who present with bilateral distal femoral shaft fractures. Treatment remains controversial and should be tailored to each patient.

Keywords: Paraplegic, intramedullary nailing, spinal cord injury, trauma.

Fractures of the lower extremities are a well-established complication in patients with long-standing spinal cord injury. Previous studies have estimated that fractures occur in 25–46% of paraplegic patients, with metaphyseal fractures of the distal femur and proximal tibia being the most common [1-3]. Traditionally, non-operative management has been the most common treatment, but as advancements in operative techniques and rehabilitation have been made, surgical intervention has become commonplace [4]. Treatment options include intramedullary nailing, plating, or a combination of both. Fixed-angle devices and intramedullary nails are reported to have better outcomes, though no clear consensus on the best approach exists [2,4]. The pathophysiology of decreased bone mineral density in patients with spinal cord injury has been previously described, with the most commonly accepted hypothesis being the mechanostat theory. A derivative of Wolff’s law, this theory proposes that mechanical strain placed on bone is kept within certain limits by the addition or removal of bone tissue. This ebb and flow results in bone strength proportional to the stress placed on it [5,6]. This constant fluctuation is accomplished by the laying down of new bone by osteoblasts and resorption by osteoclasts. In the setting of acute spinal cord injury, this balance is disrupted, leading to suppressed osteoblast activity in the first few months after injury. Following the acute phase, osteoblast activity will return to normal levels, with continued osteoclastic activity and notable bone resorption [5,7,8]. This uncoupling can be observed by a detectable elevation in serum and urine calcium levels [9]. Eventually, this disrupted balance will lead to a substantial decrease in bone mineral density and deterioration of the trabecular network in chronic spinal cord injury patients [10,11]. Lower extremity fractures in patients with spinal cord injury have often been treated conservatively; however, surgical treatment in the form of plate and screw fixation and intramedullary nail fixation has been described [12,13]. Treating these patients operatively has become progressively safer as surgical techniques have advanced [2], yet no definitive recommendations have been made. Various methods of fixation are available, including intramedullary nailing, plate fixation, and hybrid plate-nail constructs [4] with no consensus on which technique has superior outcomes. This case report describes a paraplegic patient who presented with bilateral distal femur fractures and was initially treated with bilateral intramedullary nailing. He subsequently developed a unilateral non-union requiring revision surgery with plate and screw fixation that ultimately led to painful hardware. In addition, he suffered from contralateral severe heterotopic ossification formation, overall leading to a poor quality of life.

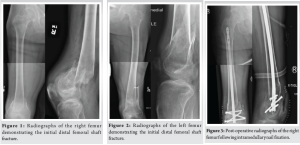

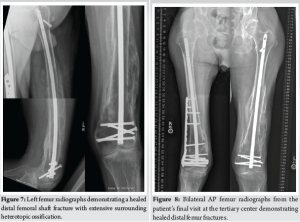

An active, independent 45-year-old male with a history of unresolved T2 paraplegia presented to the emergency department following a motor vehicle accident in which he sustained bilateral closed distal femoral shaft fractures (Fig. 1 and 2) and a left pilon fracture. Surgical intervention was recommended to maintain his current activity levels and to avoid prolonged immobilization. He underwent bilateral femoral retrograde intramedullary nail fixation (Fig. 3 and 4) and left ankle external fixation. The patient was discharged 3 days postoperatively to home with home health assistance; however, he returned the following day due to the inability to perform activities of daily living independently and was ultimately discharged to an acute care rehabilitation facility. He was successfully discharged home from the acute care rehabilitation facility and underwent outpatient removal of the left ankle external fixator and tibiotalocalcaneal (TTC) arthrodesis with a TTC nail 1 month after the initial surgery.

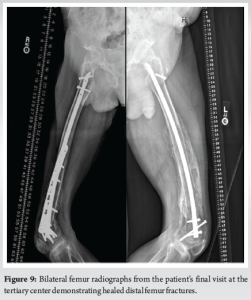

During the patient’s next follow-up visit, 1 month later, the patient complained of palpable hardware around his right knee. Repeat radiographs revealed a hypertrophic non-union with proximal migration of the nail and loosening of the distal interlocking screws (Fig. 5). He was initially treated conservatively; however, symptoms persisted for over 2 months. He then underwent removal of the right distal interlocking screws, augmentation with plate and screw fixation, and revision of the proximal interlocking screws. In a subsequent follow-up 3 weeks later, the patient noted a palpable mass around his left distal thigh. In addition, he developed a sacral decubitus ulcer that required referral to outpatient wound care. Conservative treatment with repeat imaging in 2 months was planned; however, the patient was lost to follow-up. The patient presented to the clinic 1 year later with complaints of palpable distal thigh masses bilaterally and feelings of heaviness in his legs. Radiographs revealed bilateral fracture healing with heterotopic ossification on the left, a well-fixed distal femur plate on the right, and no hardware failure (Fig. 6 and 7). The prominent left-sided heterotopic ossification and palpable right-sided distal femur plate caused significant discomfort. These complications greatly decreased his quality of life and caused him extreme distress. He was referred to a tertiary center for a second opinion, where radiographs revealed bilaterally healed distal femur fractures (Fig. 8 and 9). Removal of the right distal femur plate, left intramedullary nail, and left TTC nail was recommended to improve his quality of life. Unfortunately, the patient passed away from causes indirectly related to his orthopedic injuries before any further follow-up or surgical interventions could take place.

Lower extremity fractures are a common occurrence in patients with spinal cord injury due to the significantly increased risk for osteoporosis. The mechanism for developing osteoporosis is related to the mechanical stress placed on bone. First described by H.M. Frost, the mechanostat theory suggests that bone is regulated based on the stresses placed on it by outside forces. However, when stress is placed on bone below a certain threshold, the bone mineral density will decrease due to a homeostatic disruption [5,6]. Acutely following spinal cord injury, osteoclast and osteoblast activity both increase in activity, eventually shifting to an isolated increase in osteoclast activity with concurrent suppression of osteoblast activity. Osteoblast suppression returns to baseline levels in the chronic phase of injury; however, increased osteoclast activity persists [5,8,9]. This decreased bone turnover results in a substantial loss of bone mineral density in the first 2 years following spinal cord injury, which leads to a loss of trabecular structure in the chronic phase [5,10,11,14]. Due to this altered chemistry, heterotopic ossification and extensive callus formation are common complications of fractures in patients with SCI. Most fragility fractures in patients with spinal cord injury occur in the extra-articular regions of the distal femur, whereas the second most common location is the proximal tibia [2,3]. Surgical versus non-surgical management of fractures in patients with spinal cord injury remains controversial [15]. A 2020 study by Koong et al. suggested improved outcomes and decreased complications with surgical intervention, while Grassner et al. found no benefit [2,16]. The specific method of fixation is also debated. Chin et al. suggested rigid intramedullary nail fixation is a preferable technique in treating femur fractures in non-ambulatory, myelopathic patients, while Carbone et al. demonstrated inconclusive evidence in favor of intramedullary nail fixation, plating, or hybrid nail-plate constructs [4,17]. In this case, surgery was recommended to preserve the patient’s high-functioning activity level and allow early return to work. In patients who were active before injury, surgical treatment may prevent the significant reduction in independence and ability to perform activities of daily living seen with non-operative management and a prolonged rehabilitation course. Intramedullary nail fixation confers the ability to allow for immediate mobilization and weight bearing with less risk for wound complications. Alternatively, plate fixation or hybrid plate-nail constructs are viable options depending on fracture morphology and patient anatomy. In less active patients with increased comorbidities, non-operative management may be a preferable option to reduce possible operative complications. However, prolonged immobilization may lead to complications, including pressure ulcers and an overall decline in their independence. Of note, one study demonstrated that non-operative management does not lead to an increased likelihood of non-union [18], thus maintaining its availability as a valid treatment option. This case report describes a paraplegic patient who sustained closed fractures of the bilateral distal femurs following a motor vehicle accident. He was initially managed with bilateral retrograde intramedullary nailing; however, he later underwent revision with plate and screw fixation due to hypertrophic non-union with hardware failure. The hardware remained prominent on that side, causing painful symptoms. He also suffered from contralateral robust heterotopic calcification formation, leading to further painful symptoms. To the best of our knowledge, surgical treatment of bilateral closed distal femur fractures in paraplegic patients with intramedullary nailing has not been previously.

Clinicians should be aware of the potential complications associated with intramedullary nailing and revision open reduction internal fixation in paraplegic patients who present with bilateral distal femoral shaft fractures. Treatment remains controversial and should be tailored to each patient.

Management of distal femoral fractures in paraplegic patients is complex and must account for poor bone quality, altered healing capacity, and potential complications such as non-union and heterotopic ossification. Surgical intervention, while offering early mobilization, should be carefully considered on a case-by-case basis, with close post-operative monitoring to optimize outcomes and preserve quality of life.

References

- 1. Champs AP, Maia GA, Oliveira FG, De Melo GC, Soares MM. Osteoporosis-related fractures after spinal cord injury: A retrospective study from Brazil. Spinal Cord 2019;58:484-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Koong DP, Symes MJ, Sefton AK, Sivakumar BS, Ellis A. Management of lower limb fractures in patients with spinal cord injuries. ANZ J Surg 2020;90:1743-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Frotzler A, Cheikh-Sarraf B, Pourtehrani M, Krebs J, Lippuner K. Long-bone fractures in persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord 2015;53:701-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Carbone LD, Ahn J, Adler RA, Cervinka T, Craven C, Geerts W, et al. Acute lower extremity fracture management in chronic spinal cord injury: 2022 Delphi consensus recommendations. JB JS Open Access 2022;7:e21.00152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Craven BC, Cirnigliaro CM, Carbone LD, Tsang P, Morse LR. The pathophysiology, identification and management of fracture risk, sublesional osteoporosis and fracture among adults with spinal cord injury. J Pers Med 2023;13:966. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Frost HM. The mechanostat: A proposed pathogenic mechanism of osteoporoses and the bone mass effects of mechanical and nonmechanical agents. Bone Miner 1987;2:73-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Minaire P, Neunier P, Edouard C, Bernard J, Courpron P, Bourret J. Quantitative histological data on disuse osteoporosis: Comparison with biological data. Calcif Tissue Res 1974;17:57-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Zehnder Y, Luthi M, Michel D, Knecht H, Perrelet R, Neto I, et al. Long-term changes in bone metabolism, bone mineral density, quantitative ultrasound parameters, and fracture incidence after spinal cord injury: A cross-sectional observational study in 100 paraplegic men. Osteoporos Int 2004;15:180-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Roberts D, Lee W, Cuneo RC, Wittmann J, Ward G, Flatman R, et al. Longitudinal study of bone turnover after acute spinal cord injury. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998;83:415-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Biering‐sørensen F, Bohr HH, Schaadt OP. Longitudinal study of bone mineral content in the lumbar spine, the forearm and the lower extremities after spinal cord injury. Eur J Clin Invest 1990;20:330-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Shields RK, Dudley-Javoroski S, Boaldin KM, Corey TA, Fog DB, Ruen JM. Peripheral quantitative computed tomography: Measurement sensitivity in persons with and without spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2006;87:1376-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Nottage WM. A review of long-bone fractures in patients with spinal cord injuries. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1981;155:65-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. McMaster WC, Stauffer ES. The management of long bone fracture in the spinal cord injured patient. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1975;112:44-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Dauty M, Perrouin Verbe B, Maugars Y, Dubois C, Mathe JF. Supralesional and sublesional bone mineral density in spinal cord-injured patients. Bone 2000;27:305-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Huang D, Weaver F, Obremskey WT, Ahn J, Peterson K, Anderson J, et al. Treatment of lower extremity fractures in chronic spinal cord injury: A systematic review of the literature. PM R 2020;13:510-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Grassner L, Klein B, Maier D, Bühren V, Vogel M. Lower extremity fractures in patients with spinal cord injury characteristics, outcome and risk factors for non-unions. J Spinal Cord Med 2017;41:676-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Chin KR, Altman DT, Altman GT, Mitchell TM, Tomford WW, Lhowe DW. Retrograde nailing of femur fractures in patients with myelopathy and who are nonambulatory. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2000;373:218-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Sinnott B, Ray C, Weaver F, Gonzalez B, Chu E, Premji S, et al. Risk factors and consequences of lower extremity fracture nonunions in veterans with spinal cord injury. JBMR Plus 2022;6:e10595. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]