We report the first ever documented case of abscess formation following administration of the purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV). Clinicians should remain vigilant for even unreported adverse reactions as timely recognition and intervention can lead to a favorable outcome.

Dr. Pradeep Kumar Pathak, Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahavir Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: dr.pathak09@gmail.com

Introduction: Post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies is generally considered safe, with serious adverse events being exceedingly rare. Although abscess formation is plausible but to date, there is no documentation of abscess formation after purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV).

Case Report: This report presents a rare and first-reported case of localized abscess and axillary neuropathy following intradermal administration of PVRV in a pediatric patient. The child developed pain, swelling, and localized infection after the final vaccine dose, progressing to shoulder weakness due to axillary nerve involvement. Incision and drainage for the abscess and conservative management for axillary neuropathy resulted in full recovery.

Conclusion: The case highlights the need for vigilance in identifying and managing rare vaccine-associated adverse events.

Keywords: Rabies, purified Vero cell rabies vaccine, axillary neuropathy, adverse vaccine reaction, post-exposure prophylaxis.

Post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) for rabies using purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV) is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and is considered safe with few reported adverse effects [1]. The most common adverse events reported after PVRV are pruritic, headache, fever, and myalgia and local reactions with redness and pain at injection sites [2,3,4,5]. Over the years, PVRV have demonstrated a strong safety profile, with abscess formation at the injection site being a very rare adverse event. After a thorough and meticulous literature search, the authors found out that although local reactions are common, abscess formation has not been previously documented with PVRV [2,3,4,5]. Here, we are presenting the first case where, after PVRV, the patient not only developed an abscess in the arm but also developed axillary neuropathy.

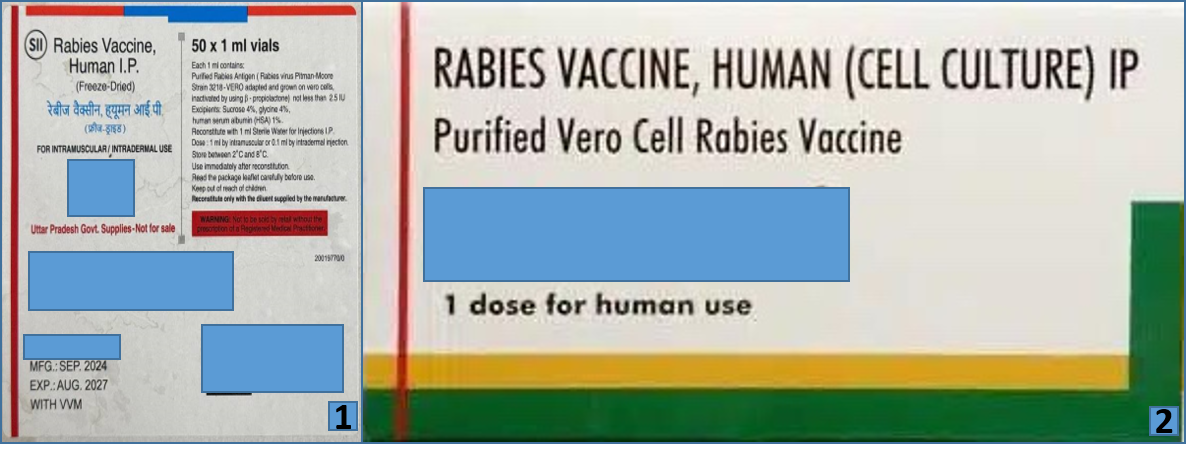

A 10-year-old previously healthy male presented to the orthopedics outpatient department with complaints of the left shoulder weakness and restricted range of motion. One month earlier, he sustained a WHO category 2 dog bite on the left calf while playing; following which he received wound care and PEP at a local primary health center [6]. His vaccination schedule included three intradermal doses of PVRV (Fig. 1 and 2) administered on days 0, 3, and 7. The first and last doses were administered in the left deltoid, while the second dose was given in the right deltoid.

The child remained asymptomatic for the first 3 days after the final injection, after which he developed localized pain, redness, and swelling at the injection site, accompanied by low-grade fever. The pain was gradually progressive and throbbing in nature, worsened by shoulder movements. Subsequently, his parents noted progressive weakness, particularly affecting shoulder abduction and flexion. A clinical diagnosis of abscess formation was made at a nearby facility, where incision and drainage were performed. Despite wound healing over the following 15 days with conservative dressing, shoulder weakness persisted, prompting referral to our center. On examination, a linear scar of approximately 1 cm was noted over the anterolateral aspect of the left shoulder, suggesting prior surgical intervention (Fig. 3). There was visible muscle wasting over the left deltoid region. The patient exhibited a complete loss of active shoulder abduction and flexion, with preserved elbow and wrist range of motion. Neurological examination revealed 0/5 power in the deltoid muscle and sensory loss in the regimental badge area, suggestive of axillary nerve involvement. Strength in other muscle groups of the upper limb was intact, with normal deep tendon reflexes. Cranial nerve and contralateral limb examinations were unremarkable.

Figure 3: Healed scar mark of around one cm over anterolateral aspect of the left shoulder.

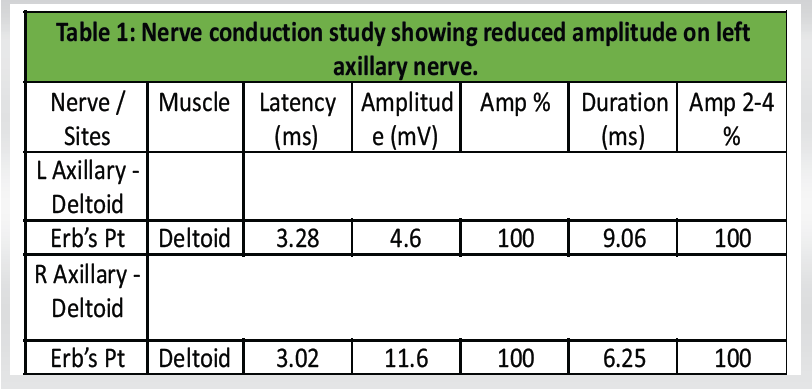

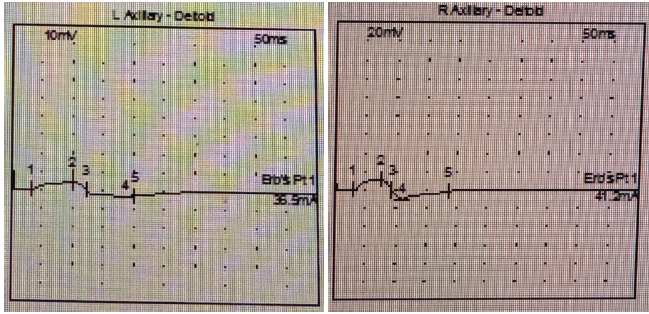

Electrodiagnostic studies showed reduced compound muscle action potential amplitude in the left axillary nerve (4.6 mV vs. 11.6 mV on the right) and prolonged duration (9.06 ms vs. 6.16 ms). Latency values were comparable bilaterally. These findings confirmed the diagnosis of the left axillary neuropathy (Table 1 and Fig. 4).

Table 1: Nerve conduction study showing reduced amplitude on left axillary nerve.

Figure 4: Comparison of action potential left and right axillary nerve.

The patient was managed conservatively with physiotherapy focused on deltoid muscle strengthening and shoulder mobilization. Serial follow-up assessments over 4 weeks revealed gradual improvement in muscle strength and range of motion. By the final follow-up, the patient had regained full deltoid power and shoulder mobility, with complete resolution of sensory deficits (Fig. 5 and 6).

Figure 5 & 6: Patient at final follow-up with fully regained deltoid power and shoulder mobility.

An extensive search of the literature on PubMed and Google Scholar was performed. The Mesh terms rabies, PVRV, abscess, complications, adverse vaccine reactions, were searched, and it was found that there were no article which has reported even a single case of abscess formation after PVRV vaccination. This case report appears to be the first documentation of abscess formation after PVRV. All intradermal and intramuscular injections do have a potential risk of infection and abscess formation. Not following proper technique and aseptic precautions, immunogenicity of the vaccine, etc., can be quoted as the probable causes. However, the rate of infection resulting from vaccine administration is surprisingly lower. For instance, the vaccine injection-related abscess formation has been reported in <1% of intradermal Bacillus Calmette–Guérin vaccines [7]. Similarly, Burton et al., reported abscess formation in only 41 cases out of 100,000 pneumococcal vaccine injections [8]. The occurrence of abscess formation with rabies vaccines is less common. There has not been a single-documented evidence of abscess formation after PVRV rabies vaccination. In a randomized, blinded, parallel-controlled phase III clinical study, Huang et al., reported that the occurrence of systemic fever and local pain was the most common adverse reactions. However, most reactions were mild to moderate in severity and transient [9]. Similar results were also found in the studies done by Zhang et al., and Hu et al. [10,11]. Most of the reactions occurred at early doses, especially the first dose, and their incidence decreased in subsequent dosage [9]. Although PVRV is generally considered safer than older neural tissue-based vaccines but still, it is still associated with rare neurological complications. These complications are primarily immune-mediated and can manifest in various forms. The most common neurological complications reported include optic neuritis and Guillain–Barre syndrome. These complications result from immune responses triggered by the vaccine, which lead to inflammation and demyelination of neural tissues [5,12,13]. In a study done by Ali et al., PVRV was shown to be generally safe. However, few neurological manifestations, such as dizziness, paresthesia, and transient headache, were reported, but there were no cases with long-term sequelae or mortality [14]. The cause of axillary nerve injury in this case can be debated. The two most probable reasons are the inflammation (Neuritis) of the axillary nerve and injury during surgical drainage of the abscess. As the incision is located anterolateral, the axillary nerve, even if it got lacerated at this location, would not lead to the weakness of abduction and extension of shoulder as most of the abductor and extensor segment of the deltoid already gets the nerve supply proximal to the point of laceration. According to the history given by the child’s parents, the axillary nerve palsy developed after abscess formation and before the surgical procedure. The most probable reason might have been the brachial neuritis due to inflammation or pressure-related changes rather than direct vaccine-induced neuropathy. Usually, the brachial neuritis has a shorter healing time and has more successful outcomes as compared to other axillary nerve injuries [15]. In cases of axillary nerve injury, return of the functions usually takes around 3–12 months [16]. Complete recovery of axillary nerve in just 6–8 weeks suggests the diagnosis of neuritis instead of laceration of axillary nerve. Axillary nerve injury is not very common in children, and to manage it, a trial of conservative management is given [17]. Usually, most of the injuries recover spontaneously. Surgical management should be reserved for the patients who do not show the signs of improvement in 4–6 months [16,17,18].

Although biologically plausible, abscess formation following PVRV remains exceedingly rare. Prompt recognition and supportive management can ensure full recovery. Vigilance during administration and monitoring for adverse events remains essential in pediatric vaccination protocols. This case report underscores the importance of recognizing uncommon complications of commonly administered vaccines.

Physicians should be prepared even for extremely uncommon complications such as abscess formation after purified chick embryo cells, as prompt diagnosis and treatment leads to a favorable outcome.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2018 – recommendations. Vaccine 2018;36:5500-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Panda M, Kapoor R. A study of adverse effects following administration of anti-rabies vaccination – a hospital based study. Natl J Community Med 2022;13:487-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Jaiiaroensup W, Lang J, Thipkong P, Wimalaratne O, Samranwataya P, Saikasem A, et al. Safety and efficacy of purified Vero cell rabies vaccine given intramuscularly and intradermally. (Results of a prospective randomized trial). Vaccine 1998;16:1559-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Ramezankhani R, Shirzadi MR, Ramezankhani A, Poor Mozafary J. A comparative study on the adverse reactions of purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV) and purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV). Arch Iran Med 2016;19:502-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Information Sheet: Observed Rate of Vaccine Reactions Rabies Vaccine. Available from: https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/pvg/global-vaccine-safety/rabies-vaccine-rates-information-sheet.pdf?sfvrsn=444396ae_4 [Last accessed on 2025 May 30]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Rabies. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/rabies [Last accessed on 2025 Aug 12]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Lotte A, Wasz-Höckert O, Poisson N, Dumitrescu N, Verron M, Couvet E. BCG complications. Estimates of the risks among vaccinated subjects and statistical analysis of their main characteristics. Adv Tuberc Res 1984;21:107-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Burton DC, Bigogo GM, Audi AO, Williamson J, Munge K, Wafula J, et al. Risk of injection-site abscess among infants receiving a preservative-free, two-dose vial formulation of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine in Kenya. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Huang X, Liang J, Huang L, Nian X, Chen W, Zhang J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of rabies vaccine (PVRV-WIBP) in healthy Chinese aged 10-50 years old: Randomized, blinded, parallel controlled phase III clinical study. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2023;19:2211896. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Zhang L, Huang S, Cai L, Zhu Z, Chen J, Lu S, et al. Safety, immunogenicity of lyophilized purified Vero cell cultured rabies vaccine administered in Zagreb and Essen regimen in post-exposure subjects: A post-marketing, parallel control clinical trial. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021;17:2547-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Hu Q, Liu MQ, Zhu ZG, Zhu ZR, Lu S. Comparison of safety and immunogenicity of purified chick embryo cell vaccine using Zagreb and Essen regimens in patients with category II exposure in China. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2014;10:1645-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Tullu MS, Rodrigues S, Muranjan MN, Bavdekar SB, Kamat JR, Hira PR. Neurological complications of rabies vaccines. Indian Pediatr 2003;40:150-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Dadeya S, Guliani BP, Gupta VS, Malik KP, Jain DC. Retrobulbar neuritis following rabies vaccination. Trop Doct 2004;34:174-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Ali W, Ismail Tajik M, Ali I, Gul A, Khan JZ. Safety of purified Vero cell rabies vaccine manufactured in Pakistan: A comparative analysis of intradermal and intramuscular routes. Curr Med Res Opin 2023;39:789-96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Patel D, Shannon V, Adissem Z, Bassett J, Ebraheim N. Axillary nerve injury: Current concept review. J Orthop Rep 2022;1:100050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Canale ST, Beaty JH, Campbell WC. Campbell’s Operative Orthopaedics. 12th ed. St. Louis, Missouri , London: Mosby; 2012. p 3300-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Tyagi A, Drake J, Midha R, Kestle J. Axillary nerve injuries in children. Pediatr Neurosurg 2000;32:226-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Steinmann SP, Moran EA. Axillary nerve injury: Diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2001;9:328-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]