These types of complex injuries demand individual surgical planning Restoring bony and soft-tissue stabilizers is crucial for elbow stability Structured rehabilitation and monitoring are essential to prevent complications This case reinforces that early intervention, skilled surgical repair, and dedicated rehab can lead to excellent recovery, even in complex polytrauma scenarios

Dr. Amir Suhail, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Marudhar Industrial Area, 2nd Phase, M.I.A. 1st Phase, Basni, Jodhpur - 342005, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: suhail.amir22@gmail.com

Introduction: The terrible triad of the elbow–consisting of elbow dislocation, radial head fracture, and coronoid process fracture–is a challenging injury to treat. Bilateral occurrence is exceptionally rare, particularly in polytrauma patients, and presents significant surgical and rehabilitation challenges.

Case Report: We present a case of a young male who sustained bilateral terrible triad injuries with an associated right both-bone forearm fracture following a fall from a height. On arrival, he was managed as per the advanced trauma life support protocols. Initial management followed a damage control orthopedics strategy, including temporary stabilization and wound care. After 15 days of intensive care unit stabilization, definitive staged procedures were carried out. These included bilateral radial head replacements, coronoid fixation (suture pull-out technique on the left and screw fixation on the right), and open reduction and internal fixation of the forearm. Elbow surgeries were staged due to the patient’s general condition and associated injuries. Early rehabilitation was initiated under supervision. At 1-year follow-up, the patient had a good range of motion, radiological union, and excellent functional scores.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of early recognition, individualized staged surgical planning, and structured rehabilitation for achieving successful outcomes in rare and complex bilateral terrible triad injuries in polytrauma patients.

Keywords: Terrible triad, bilateral elbow dislocation, radial head replacement, polytrauma, coronoid fracture.

Hotchkiss [1] first described the “terrible triad” as a combination of three injuries: a fracture of the radial head, a fracture of the coronoid process of the ulna, and a posterior or posterolateral dislocation of the ulnohumeral joint. This term was used, as these injuries often result in poor bone healing and long-term limitations in the range of motion (ROM). This injury is considered difficult to treat because the substantial instability of the elbow increases the likelihood of joint stiffness and the development of secondary osteoarthritis, often leading to a poor clinical outcome. Terrible triad injury usually arises from valgus stress on the elbow, forearm supination, and axial compression [2,3]. This trauma can lead to damage in the radial collateral ligament complex, often extending to the joint capsule and sometimes involving the ulnar collateral ligament compartment, resulting in significant elbow instability [3]. Timely intervention, including early reduction and tailored treatment, plays a key role in achieving better functional and radiological outcomes [2]. The primary goal in treating these injuries is to reconstruct the stabilizing bony structures of the elbow, transforming a complex dislocation into a simpler one. Although accurately identifying these injuries can be challenging, prompt management and addressing both bony and soft tissue injuries is a key factor in having a favorable prognosis [4]. The lack of extensive research and a standardized treatment protocol complicates the decision-making process for such cases, increasing the risk of joint stiffness and secondary arthrosis [5]. Therefore, a deep understanding of elbow biomechanics and anatomy, along with ensuring stability and early movement, is essential for achieving a positive outcome. Hereby, we report a rare and complex case of elbow trauma characterized by bilateral terrible triad with right forearm bone fracture in a polytrauma patient.

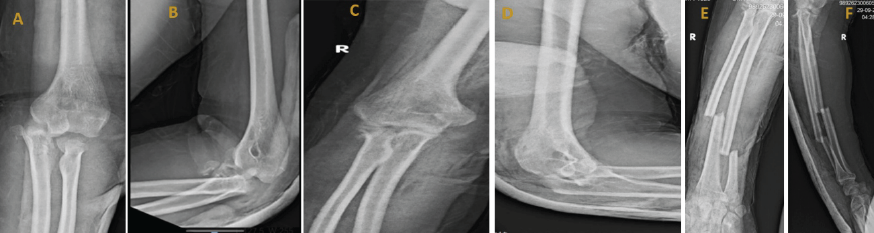

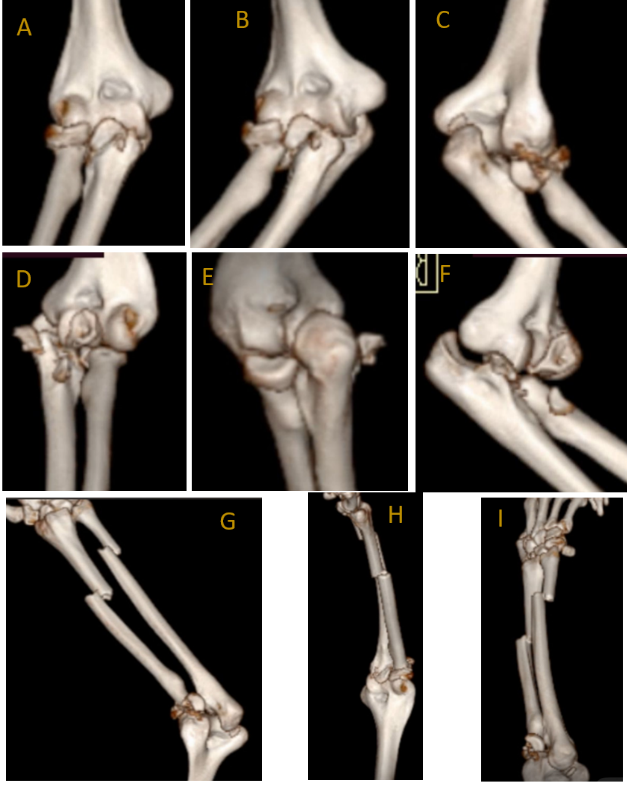

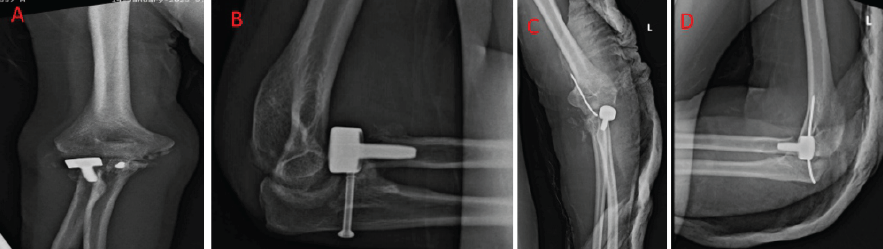

A right-hand dominant male in his late 20s, with a known history of schizophrenia on regular medication, presented to the emergency department of a tertiary care center after sustaining a fall from a height of 18 feet. On arrival, he was managed according to advanced trauma life support protocols. The primary survey was conducted immediately, confirming a patent airway with cervical spine protection, spontaneous breathing with symmetrical chest movement, and hemodynamic stability (C-spine cleared clinically and later radiologically). Circulation was assessed with bilateral feeble lower limb pulses, and intravenous access was established. There were no signs of active bleeding or tension pneumothorax. A focused neurological examination revealed that the patient was conscious and oriented, with no evidence of head injury or spinal cord involvement. Secondary survey revealed multiple orthopedic injuries and soft-tissue wounds over bilateral limbs, resulting in swelling and restricted ROM in both elbows, left knee, and both ankles, along with pain and tenderness over the lower back. Initial radiographic (Fig. 1) and clinical assessments revealed closed terrible triad injury of the right elbow and an open grade 1 terrible triad injury on the left elbow, i.e., bilateral dislocation of elbows, with radial head (right- Mason type III, left- Mason type IV) and coronoid process-associated fractures (Regan–Morrey type III- right, type II- left). Additional injuries included a right-side forearm fracture, comminuted open grade 2 distal femur and patella fracture on the left side, undisplaced fractures of the scaphoid, lunate, triquetrum, and distal radius on the left, open calcaneal and talar fractures on the right, closed pilon fracture, L1 vertebral body fracture (AO Type C), and multiple metatarsal and cuneiform fractures of the left foot. Three-dimensional (3D) computed tomography reconstruction of the elbows showed coronoid process fracture and comminuted radial head fracture on both sides (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Pre-operative X-rays of left elbow (a) anteroposterior and (b) lateral view, right elbow (c) anteroposterior and (d) lateral view, right forearm (e) anteroposterior and (f) lateral view.

Figure 2: Pre-operative computed tomography scan 3D reconstruction of right elbow (a, b, c) and left elbow (d, e, f), right elbow with forearm (g, h, i).

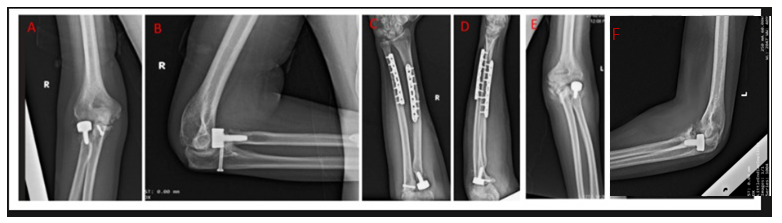

Considering the polytrauma status and complexity of injuries, the patient was managed according to the “life over limb” principle. Initial surgical intervention followed a damage control orthopedics strategy. The patient first underwent articular reconstruction of the distal femur along with application of a knee-spanning external fixator for stabilization. Closed reduction and temporary stabilization of both elbows were performed using a K-wire and slab support. Wound debridement was also carried out at this stage to minimize the risk of infection. Following these initial procedures, the patient required intensive care unit stabilization for 15 days before further definitive surgeries could be planned. In the 3rd week, spinal fusion from D11 to L2 was performed for the L1 burst fracture. Two weeks later, after soft tissue recovery, the left distal femur was fixed with a locking plate, and the right calcaneum and medial malleolus were stabilized using cannulated screws in a single session. In the 5th week, the elbows were managed in a staged manner, as the patient’s debilitated condition rendered him unfit for simultaneous and prolonged surgical procedures. The patient was operated on in a supine position with the arm resting over the hand table. After induction of general anesthesia, an examination under anesthesia was performed before initiating the procedure. Antibiotics were given, and the tourniquet was applied. For the left elbow, the Kocher approach was used for radial head replacement, and the anteromedial approach was taken to fix the coronoid fracture with 1 fiber wire through the suture pull-out technique. Elbow stability was assessed both clinically and under an image intensifier. The left elbow was found to be unstable, and therefore, 1 ulno-humeral K-wire was inserted. Later that week, the right elbow was also addressed. For the right side, both bone forearm fractures were first fixed with open reduction and internal fixation with a locking compression plate. After this, radial head replacement and coronoid fixation with 1 cancellous cannulated screw were done through the Kocher approach (Fig. 3). The right elbow was found to be stable; the total surgical time taken was 160 min for the right side and 130 min on the left side.

Figure 3: Immediate post-operative X-rays of right elbow (a) anteroposterior and (b) lateral view and left elbow (c) anteroposterior and (d) lateral view

Bilateral above-elbow posterior slab support was provided for 2 weeks to facilitate soft-tissue healing. Suture removal and removal of the ulno-humeral K-wire were performed 2 weeks postoperatively, followed by gradual progression to active elbow rehabilitation. Pronation-supination exercises, along with elbow flexion and extension exercises, were initiated 2 weeks after surgery. Indomethacin was administered to prevent myositis ossificans. The patient was advised to do activities of daily living and avoid heavy lifting. The patient tolerated the staged procedures well. His post-operative course was uneventful, and he gradually began bed-based rehabilitation. At discharge, he was stable, oriented, and advised regular follow-up for wound care, stitch removal, and progressive physiotherapy.

Outcome and follow-up

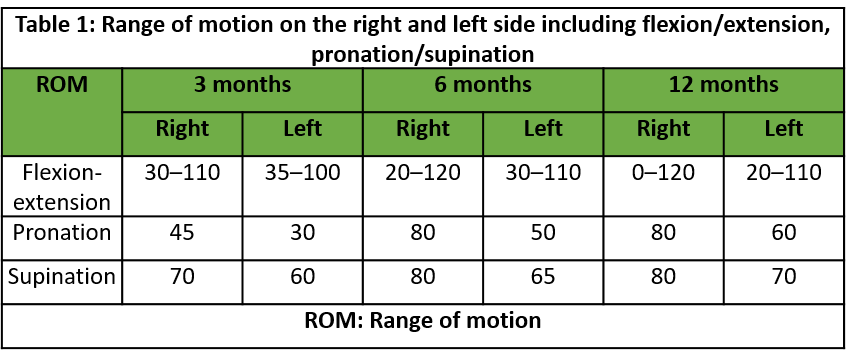

Follow-up was done at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively. They were examined clinically, and a radiographic and functional outcome was done using different scores. During the first 8 weeks, the range of mobility increased by 10°/week. At the end of 3 months, both functional and radiological outcomes were satisfactory (Fig. 4). The ROM on the right and left side, including flexion/extension, pronation/supination, was measured and documented at 3, 6, and 12 months (Table 1).

Figure 4: Follow-up range of motion at 3 months. Right elbow flexion and extension (a and b); left elbow flexion and extension (c and d); forearm pronation and supination (e and f).

Table 1: Range of motion on the right and left side including flexion/extension, pronation/supination

A muscle-strengthening program was started in the 4th month to strengthen the stabilization role of periarticular muscles [6]. At the 6-month follow-up, a clinical and radiological assessment (Figs. 5 and 6) was done, and the patient showed steady improvement in ROM in both elbows, demonstrating significant progress compared to pre-operative status. On radiological assessment, no elbow instability was seen, assessed by the radiocapitellar line made by passing through the middle of the radius shaft passing through the capitellum on lateral elbow radiographs in any degree of elbow flexion.

Figure 5: Post-operative follow up (at 6 months) X-rays of right elbow (a) anteroposterior and (b) lateral view, right forearm (c) anteroposterior and (d) lateral view, and left elbow (e) anteroposterior and (f) lateral view.

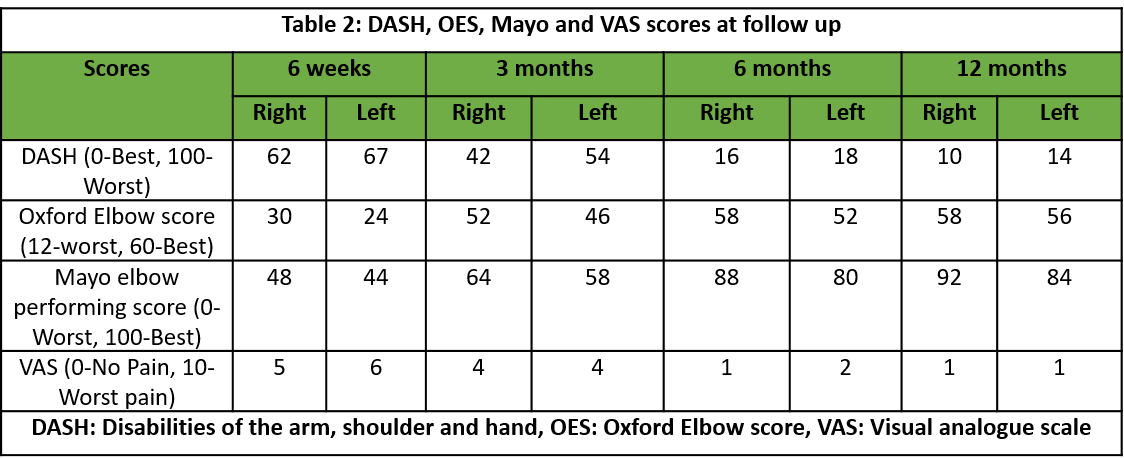

Both elbows were stable at the follow-up of the patient at the outpatient department, indicating a positive outcome. In addition, functional recovery was assessed using the Oxford Elbow score (OES), a validated tool for measuring elbow function and quality of life. The patient had progressive improvement in OES, disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and hand (DASH), and Mayo scores, reflecting enhanced function and overall satisfaction with the surgical outcome (Table 2).

Table 2: DASH, OES, Mayo and VAS scores at follow up

This case underscores the importance of timely surgical intervention and strategic management in optimizing functional outcomes for patients with bilateral terrible triad elbow injuries in the setting of polytrauma. It also highlights the pivotal role of meticulous post-operative care and structured rehabilitation protocols in facilitating recovery and minimizing complications in such complex, high-energy injuries.

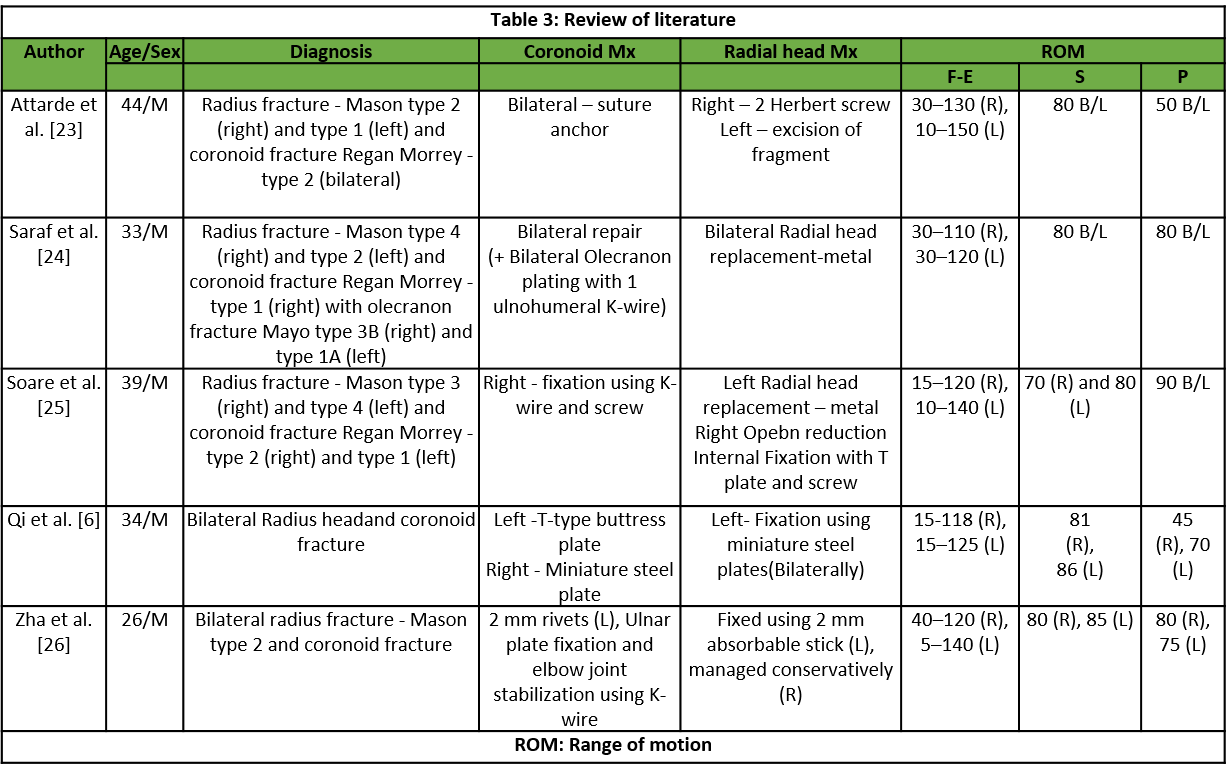

The mechanism of injury plays a crucial role in determining the severity of a terrible triad injury. This complex injury follows a specific sequence of events. In this case, the patient fell from a height with the elbows extended and the forearms in supination. The axial force transmitted through the ulna-humeral joint led to a posterior dislocation, resulting in fractures of both the radial head and the coronoid process. The primary goals in treating a terrible triad injury are to restore elbow joint congruency, ensure stability, and enable early mobility to prevent complications. Standard treatment protocols, such as those proposed by Pugh et al., [7] focus on anatomical restoration of the humeroradial joint, reduction and fixation of the coronoid process fracture, and repair of the joint capsule and ligamentous injuries, including the lateral collateral ligament and, when necessary, the medial collateral ligament (MCL). Few cases have been published in the past; the summary of the same is shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Review of literature

Reddy [8] published a case report of a bilateral terrible triad injury managed with radial head replacement (metal) along with coronoid repair with Ethibond suture on both sides. ROM in the follow-up was 0–120° bilaterally, with a Mayo score of 92 on the right side and 85 on the left side. Jlalia et al. [9] reported a pediatric case of a bilateral terrible triad with a radius head fracture (Mason type 3) and coronoid fracture (Regan–Morrey type 3) with elbow dislocation on both sides. Closed reduction was done, and fractures were managed conservatively with the above-elbow slab with a good outcome on follow-up. Terrible triad injuries involve both bony and soft tissue components. Proper soft-tissue repair is essential for joint stability. A gradual rehabilitation protocol ensures that a reasonable ROM is achieved, allowing the patient to regain functional activity as soon as possible. Since the injury was more severe on the left side, the ROM was comparatively lower, likely due to soft-tissue damage. Stiffness is the most common complication following a terrible triad injury, and this was observed in our patient on the left side [10,11]. On assessment, it was found to be due to heterotopic ossification (HO), which was then tackled with regular follow-up and a supervised physiotherapy protocol. Other complications found in these types of injury that need to be examined thoroughly include instability and ulnar neuropathy [3]. Because of the high risk of arthrosis and instability, resection arthroplasty is not recommended in this type of case [12]. Although Watters et al., [13] concluded that radial head arthroplasty, when compared to fixation, afforded excellent ability to obtain elbow stability. Egol et al. [14] stated that the management of radial head fracture in the form of fixation or arthroplasty should be decided based on the radial head fracture pattern. Chen et al. [15] did a systematic review and concluded that the most common complication in terrible triad injury not requiring surgical treatment is HO followed by arthrosis of the ulnohumeral joint. Naoki Miyazaki et al. [16] concluded that residual instability can be prevented by stable fixation of the coronoid, radial head fixation/replacement, and repairing the lateral ligament complex with or without MCL repair. In their study, they had 2 cases with ulnar nerve neuropraxia and a case of stiffness of the elbow due to HO. Stambulic et al. [17] performed a scoping review on surgically treated terrible triad injuries and found an average Mayo elbow performance score. (MEPS) of 90 in 1609 patients and an average DASH score of 16 in 441 patients, highlighting a good functional outcome and suggesting marked improvement of outcome scores since the term was coined. A retrospective study done by Ikemoto et al. on 20 patients with terrible triad injuries managed surgically obtained good functional results with average MEPS and DASH scores found to be 14.2 and 84, respectively, with good-to-excellent functional ROM [18]. Ormiston and Rory [19] in 2025 published their longest follow-up of 20 patients with acute, isolated, surgically managed terrible triad injuries and concluded a long-term good functional outcome. In their study, the average length of follow-up was 18.8 years. The mean MEPS and DASH were 88 and 12.3, respectively. A similar high-energy injury pattern was reported by Boufettal and Gourinda involving a perilunate dislocation with ipsilateral terrible triad injury [20]. Early diagnosis and urgent surgical fixation of both joints resulted in good functional recovery. Zandi et al., reported a terrible triad with ipsilateral distal radius, scaphoid fractures, and triceps rupture, where elbow instability persisted until the triceps tear was repaired through a posterior approach [21]. This highlights the need to consider soft-tissue injuries when instability remains unexplained. Partheeswar et al. [22] documented a terrible triad with an associated ipsilateral proximal humerus fracture, managed in a staged manner due to the patient’s polytrauma status. Bilateral terrible triad injuries of the elbow represent an exceedingly rare and demanding clinical scenario, especially in patients with polytrauma. With both upper limbs affected, patients face complete dependence for essential daily functions such as eating, hygiene, dressing, and mobility. This sudden loss of autonomy can significantly impact mental health, often leading to emotional distress, anxiety, or depression, particularly in those who were previously independent. From a surgical perspective, treating complex injuries in both elbows raises critical questions about whether to operate on both sides in a single session or to stage the procedures. While single-session surgery may minimize hospital stay and exposure to anesthesia, it increases intraoperative duration, blood loss, and complexity of post-operative care. Staging surgeries may be safer for high-risk patients, but they delay full recovery. The surgical process itself is more intricate, requiring precise handling of small or fragmented bone pieces and repair of key stabilizing ligaments on both sides. This heightened technical demand increases the risk of neurovascular injury. Rehabilitation is equally complicated–early movement is essential to prevent joint stiffness and HO, yet activating both elbows simultaneously is often impractical due to pain, fatigue, and logistical limitations such as brace application or therapy participation. Post-operative care poses unique challenges; splinting both arms restricts positioning and complicates sleep, while managing pain becomes more difficult. Strong painkillers may impair cognitive and physical function, and bilateral nerve blocks–though effective–can leave both arms temporarily nonfunctional. Furthermore, the risk of complications is significantly greater when both elbows are involved. These include HO, post-traumatic arthritis, instability, nerve damage, and higher chances of infection. Long-term outcomes often involve persistent stiffness and limited ROM, affecting tasks such as lifting, personal grooming, and reaching overhead. On a broader level, the social and economic implications are serious. Patients may lose their ability to work, particularly in jobs requiring manual labor, and face higher treatment costs due to dual surgeries, extended rehabilitation, and long-term care needs. This report presents a rare case of bilateral terrible triad injuries of the elbows, treated using different protocols for each side. A combination of clinical examination, radiological imaging, biomechanical analysis, and fracture fragment anatomy guided the surgical plan. Addressing every component of the injury intraoperatively and dedicated post-operative elbow physiotherapy and rehabilitation helps in the management of this type of case.

Bilateral terrible triad injuries of the elbow in the context of polytrauma represent an exceedingly rare and formidable challenge. Optimal outcomes are achieved through early diagnosis, prioritization of systemic stabilization, and carefully staged surgical intervention tailored to the patient’s physiological status. Definitive fixation of both osseous and soft-tissue stabilizers, combined with a structured rehabilitation protocol, can restore joint stability, minimize complications, and enable functional independence, even in complex high-energy injuries.

Bilateral terrible triad injuries in polytrauma demand meticulous planning, staged surgical intervention, and coordinated rehabilitation. A multidisciplinary approach and patient-specific strategies are crucial to achieving optimal outcomes in these challenging scenarios.

References

- 1. Hotchkiss RNC, Court-Brown C, Heckman JD, Bucholz RW. Fractures and Dislocations of the Elbow. In: Bucholz RW, Heckman JD, Court-Brown CM, Green DP, editors. Rockwood and Green’s Fractures in Adults. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. O’Driscoll SW, Jupiter JB, King GJ, Hotchkiss RN, Morrey BF. The unstable elbow. Instr Course Lect 2001;50:89-102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. O’Driscoll SW, Morrey BF, Korinek S, An KN. Elbow subluxation and dislocation. A spectrum of instability. Clin OrthopRelat Res 1992;280:186-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Armstrong AD. The terrible triad injury of the elbow: Curr Opin Orthop 2005;16:267-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Santos AD, Tonelli TA, Matsunaga FT, Matsumoto MH, Netto NA, Tamaoki MJ. Results of surgical treatment of the terrible triad of the elbow. Rev Bras Ortop. 2015;50(4):403-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Qi XY, Zhang Q, Liu Z, Liu G. Bilateral terrible triad injury of the elbow joints: A case report. Int J Clin Exp Med 2018;11:9813-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Pugh DM, Wild LM, Schemitsch EH, King GJ, McKee MD. Standard surgical protocol to treat elbow dislocations with radial head and coronoid fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol 2004;86:1122-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Reddy J. Traumatic bilateral terrible triad of elbow with left trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocation and right lunate dislocation. Int J Curr Res 2016;8:35255-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Jlalia Z, Abid H, Kamoun K, Jenzri M. Bilateral terrible triad of elbow: A pediatric case report. Ann Clin Case Rep 2016;1:1191. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Attarde D, Patil A, Pradhan C, Puram C, Ansari H, Sancheti P. Terrible triad injuries around the elbow: It is still a puzzle? Prospective study. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:282-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Ben Abdellah A, Ben Salah S, Darraz S, Tebbaa A, Jelti O, Mokhtari O, et al. Terrible triad injury of the elbow: A PROCESS-compliant surgical case series from Eastern Morocco. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2022;78:103914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Gomide LC, de Oliveira Campos D, Ribeiro JM, de Sousa MR, do Carmo TC, Andrada FB. Terrible triad of the elbow: Evaluation of surgical treatment. Rev Bras Ortop 2011;46:374-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Watters TS, Garrigues GE, Ring D, Ruch DS. Fixation versus replacement of radial head in terrible triad: Is there a difference in elbow stability and prognosis? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:2128-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Egol KA, Immerman I, Paksima N, Tejwani N, Koval KJ. Fracture-dislocation of the elbow functional outcome following treatment with a standardized protocol. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis 2007;65:263-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Chen HW, Liu GD, Wu LJ. Complications of treating terrible triad injury of the elbow: A systematic review. PLoS One 2014;15:e97476. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Naoki Miyazaki A, Santos Checchia C, Fagotti L, Fregonez M, Doneux Santos P, da Silva LA. Evaluation of the results from surgical treatment of the terrible triad of the elbow. Rev Bras Ortop 2014;49:271-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Stambulic T, Desai V, Bicknell R, Daneshvar P. Terrible triad injuries are no longer terrible! Functional outcomes of terrible triad injuries: A scoping review. JSES Rev Rep Tech 2022;2:214-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Ikemoto RY, Murachovsky J, Bueno RS, Nascimento LG, Carmargo AB, Corrêa VE. Terrible triad of the elbow: Functional results of surgical treatment. Acta Ortop Bras 2017;25:283-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Ormiston R, Hargreaves D. “The treatable triad” long-term functional results of surgically treated acute isolated terrible triad injuries: An 18-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2025;34:114-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Boufettal M, Gourinda H. Floating forearm: A rare association of perilunate dislocation and terrible triad injury of the elbow. J Orthop Case Rep 2022;12:???. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Zandi R, Biglari F, Rad SB, Karami A, Sadighi M, Jafari M, et al. Terrible triad of the elbow with ipsilateral complete triceps tearing, distal radius and scaphoid waist fracture: A case report. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:63-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Partheeswar S, Sathiyaseelan N, Vinodh JB, Vignesh A, Rathi NK. Management of ipsilateral terrible triad injury of elbow and concomitant proximal humerus fracture: A case report and literature review. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:109-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Attarde D, Patil A, Vinayak U, Sancheti P, Shyam A. An interesting case of bilateral terrible triad elbow. J Orthop Rep 2023;2:100149. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Saraf A, Bishnoi S, Hussain A, Aggarwal S. Bilateral elbow terrible triad case report. J Bone Joint Dis 2022;37:89-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Soare G, Baciu CC, Ion Popescu G, Dragomirescu L, Vișoianu A. Bilateral terrible triad injury of the elbow – a case report. Roman J Emerg Surg 2020;1:15-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Zha G, Niu X, Yu W, Xiao L. Severe injury of bilateral elbow joints with unilateral terrible triad of the elbow and unilateral suspected terrible triad of the elbow complicated with olecranon fracture: one case report. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:14214-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]