MIPO offers a less invasive alternative to ORIF in distal fibula fractures, providing reduced operative morbidity while maintaining comparable radiological outcomes.

Dr. Satyaki Dandi, Department of Orthopaedics, Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital, Kolkata, West Bengal, India. E-mail: satyakivck22@gmail.com

Introduction: Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) has been proven to be better than open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) for treating various long bone fractures. However, there are not many studies on distal fibula fracture treatment by MIPO. This study compares the clinical and radiological outcomes and quality of life of the MIPO with ORIF in the treatment of fractures of the distal fibula within a 6-month follow-up.

Materials and Methods: Patients undergoing MIPO (n = 27) and ORIF (n = 30) for distal fibula fractures (Danis-Weber type B and C) treatment from 2023 to 2024 were compared. All distal fibular fractures that were planned for surgical treatment (Danis-Weber type B and Danis-Weber type C) were incorporated (ORIF n = 30, MIPO n = 27). Post-operative pain was evaluated using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS), while quality of life was measured using SF-12 scores preoperatively and postoperatively. Complications such as infections and non-union were also assessed alongside radiological outcomes.

Results: The complication rate was higher in the ORIF group (30%) in comparison with the MIPO group (22.2%). Specific complications such as non-union, infections, and post-operative pain at the 24th week were more frequent in the ORIF group. The MIPO group showed better physical and mental SF-12 scores at various follow-ups. In addition, tibiofibular overlap was significantly lower in the ORIF group, while other radiological measures were similar across the two groups.

Limitations: This study has several limitations. First, it is retrospective in design, which inherently limits the ability to establish causal relationships between surgical technique and outcomes. Retrospective data collection may be influenced by recall bias, incomplete documentation, and selection bias, which may affect the reliability of findings. Second, the sample size is relatively small (n = 57; MIPO = 27, ORIF = 30), which restricts the statistical power to detect significant differences, especially for rare complications. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to a broader population. Third, the follow-up duration is limited to 6 months. This period may be inadequate to evaluate long-term outcomes such as hardware failure, post-traumatic arthritis, late soft-tissue irritation, or the need for implant removal. Fourth, although the study focused on Danis-Weber Type B and C fractures, no further stratification or subgroup analysis was performed based on fracture complexity, comminution, or associated injuries, which could act as confounding variables. Fifth, the study lacks randomization, which can introduce selection bias. The decision to use MIPO or ORIF may have been influenced by surgeon preference or patient-specific factors such as soft-tissue condition or comorbidities. Sixth, the outcome assessors were not blinded to the surgical method, potentially introducing observer bias in evaluating clinical and radiological outcomes. Seventh, while VAS and SF-12 were used for quality-of-life and pain assessments, validated ankle-specific scores such as the Olerud-Molander Ankle score or the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society score were not included. Eighth, radiological evaluation relied solely on plain radiographs and did not compare with the contralateral side. Advanced imaging such as magnetic resonance imaging or computed tomography was not routinely used, which could underestimate syndesmotic injuries. Ninth, the study was conducted at a single tertiary care center. Thus, its findings may not be representative of outcomes in other institutions with differing resources and levels of surgical expertise. Tenth, no cost-effectiveness analysis was performed. Although MIPO may require specialized instruments and training, the economic viability of adopting this approach, especially in resource-limited settings, was not assessed. Eleventh, while a standardized rehabilitation protocol was followed, adherence to the protocol by patients was not reported, and could influence outcomes such as functional recovery and pain. Twelfth, no subgroup analysis was conducted based on patient age, comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, vascular disease), or bone quality (e.g., osteoporosis), all of which can impact healing and complication rates. Finally, many observed outcome differences were not statistically significant, possibly due to limited sample size, even though they may have clinical relevance. In addition, the study does not account for the surgeon’s learning curve, which could have affected the operative efficiency or complication rates.

Conclusion: In this study, MIPO was better than ORIF in terms of the overall complication rate in the treatment of distal fibula fractures.

Keywords: Fibula, open reduction and internal fixation, minimally invasive percutaneous plate osteosynthesis.

Fractures of the ankle are one of the most prevalent fractures to be managed by orthopedic surgeons [1]. It is mainly treated through open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) [2]. Ankle fracture involving the distal fibula is difficult to treat due to associated comminution, fracture dislocation, and soft-tissue involvement [3,4]. Numerous articles had shown that harm occurred in soft-tissue around the fracture in the traditional surgical method, thus proving the importance of maintaining biological status [5,6,7]. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) maintains vascular supply by perforating artery and nutrient artery more than the conventional open method [8,9,10]. MIPO provides a better surgical access point and lessens the invasiveness. The success rate of MIPO increased with the introduction of the new angular stable screw-plate systems [7,11]. There are some drawbacks of MIPO concerning the inability of direct visualization and manipulation of fracture [11], but it has fracture healing similar to ORIF with less incidence of non-union [3,12,13,14]. There have been many studies in the last decade showing the outcome of MIPO in femoral and tibial fractures, but only a few studies discuss the effect of MIPO in the treatment of distal fibula fractures [2,3,5,6,7]. Only two of those studies compare with MIPO and ORIF.

These studies showed surgery-related complications such as non-union, infection, and delayed wound healing were lower among the MIPO group than the ORIF group. Few studies compare the quality of life of patients undergoing two procedures in the post-operative period. This retrospective study was done to compare post-operative pain, complications, and quality of life in the post-operative period in both MIPO and conventional ORIF for treating fractures of the distal fibula (Danis-Weber type B and C). The hypothesis suggested that MIPO might lead to better outcomes both clinically and radiologically, with lower complication rates, and better quality of life compared to ORIF. This study was done to provide more evidence to answer this question.

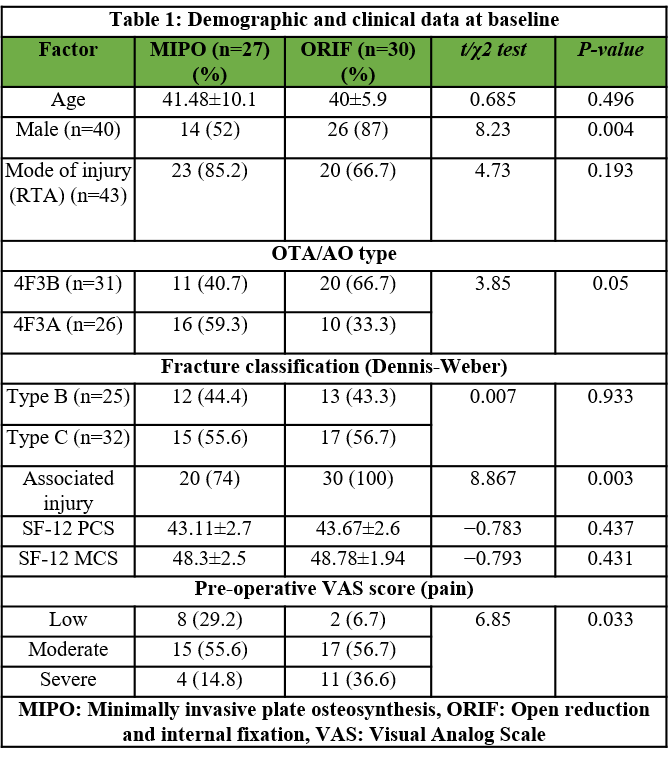

This retrospective analysis was conducted at Nil Ratan Sircar Medical College and Hospital in Kolkata, West Bengal. The study received approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee and adhered to strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology guidelines [15]. Patients undergoing MIPO and ORIF for treatment of a distal fracture of the fibula between 2023 and 2024, who gave consent, were included in the study. The patients were then included in groups according to the surgery techniques used for treatment to compare the outcome. Fractures were categorized with the Danis-Weber classification as mentioned by both the orthopedic trauma association and the Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Osteosynthesefragen (AO Foundation) [16,17]. All distal fibular fractures requiring surgical treatment, specifically Danis-Weber type B fractures and Danis-Weber type C fractures, were included in the study. Patients with complex Pilon fractures (AO type 43 C3), Maisonneuve fractures (AO type 44 C3), fractures in both legs, and patients who had prior surgery at the fracture site were excluded. Patients with existing conditions that could potentially affect the recovery and functional outcomes, such as congenital malformations or neurological disabilities, or open fractures, were also excluded. In total, 57 patients meeting the inclusion and exclusion criteria were added to the study. The pre-operative demographic and clinical findings of the two groups are expressed in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic and clinical data at baseline

Patients were evaluated for post-operative pain using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS), categorized into four groups: “no pain” (VAS = 0), “low” (VAS = 1–3), “moderate” (VAS = 3–5), and “severe” (VAS = 5–10) [18]. The quality of life for patients was measured by using the SF-12 survey, which measures both physical and mental health [19].

Description of surgical technique

Recommendations from the AO Foundation were followed for both surgical procedures [20]. Surgery was performed after soft-tissue swelling subsided, and in cases of severe trauma or subluxation, a temporary external fixator was used. Patients were positioned supine on a radiolucent table, with all fixator components removed when applicable. In the ORIF group, skin was incised near the lateral part the fibula, allowing for fracture reduction with Weber clamps and insertion of a lag screws if necessary. Plates were applied using several types based on fracture morphology and bone quality. For the MIPO group, plate size was predetermined from pre-operative planning. A tourniquet was applied, and a small incision was made to place the locking drill sleeve for plate, which was pushed subcutaneously along the fibula. Fracture reduction was assessed fluoroscopically, and if necessary, closed reduction was performed. After fixing the plate with locking screws, syndesmotic stability was tested, and if instability was present, screws were used for stabilization. A stress radiograph was taken, and if 5 mm or more is exceeded in the medial clear space, a deltoid ligament repair was conducted. Skin was sutured at end of procedure.

Post-operative management

The same post-operative follow-up and rehabilitation practice was followed among both groups. In all cases, after stabilization of the ankle using a VACOPed walker (Oped, Cham, Switzerland), the foot was positioned at a 90° angle. For the first 6 weeks, partial weight bearing with a maximum load of 15 kg was allowed. If the wound healed properly, training for range of motion began after 2 weeks. After 6 weeks of operative, if fractures radiologically consolidated, full weight bearing was allowed. For cases involving trans-syndesmotic fixation, after 10–12 weeks of surgery, the screws were removed.

Follow-up

Clinical follow-up examination, pain scores (VAS) and quality of life (SF-12 pcs and SF-12 mcs) were recorded on day 0, day 15, 6 weeks, 12 weeks, and 24 weeks. During the 6-week follow-up, radiologic examination was done. Time was measured from incision to wound closure was considered as the total operation time, and the length of hospital stay post-surgery was also recorded. Post-operative complications were noted and mentioned as nonunion, infections due to fractures, and delayed wound-healing. A non-union was characterized as a fracture that remained unhealed for 3 consecutive months [21]. Fractures were examined for healing by both the operating surgeon and a trained radiologist using plain radiographs. The lack of pain while bearing weight, along with the bridging of at least three out of four cortices in both anteroposterior and lateral views, was regarded as an indication of bone healing. In cases of confusion, a computed tomography scan was performed. Disagreements were discussed between both parties to reach an agreement. To evaluate radiological findings in post-operative, follow-up, mortise view was used to compare factors such as the talocrural angle, clear spaces, tibiofibular overlap, and talar tilt angle across both procedures.

Statistical analysis

Ms Excel and the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 16.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) were utilized for management and statistical analysis of data. Continuous values were demonstrated in mean and standard deviations, and a two-tailed unpaired t-test was used to compare between groups with two different procedures. Discrete variables were shown as frequencies and percentages, and the Chi-square test (χ2) was used to differentiate between two groups. The alpha level for all tests was set at 0.05 to become a statistically significant threshold and expressed in P<0.05 when statistically significant. For this analysis, an alpha level of 5% and a power of 80% was set.

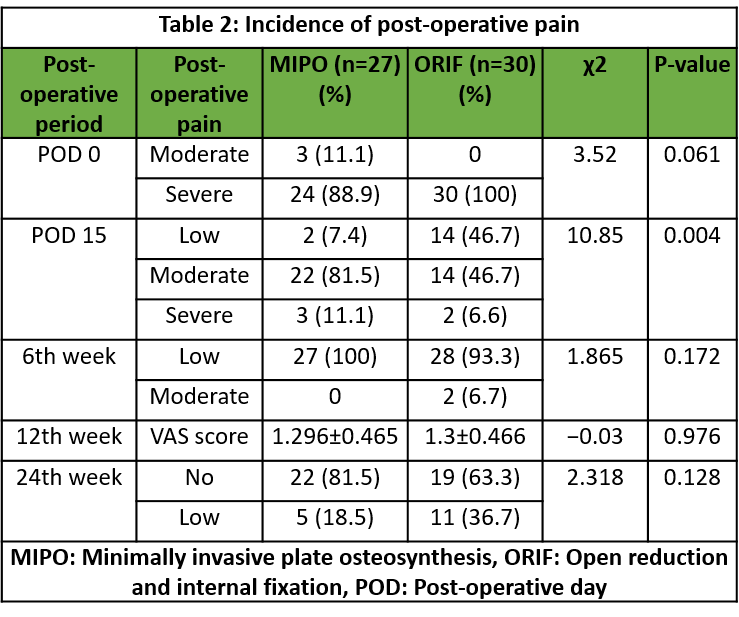

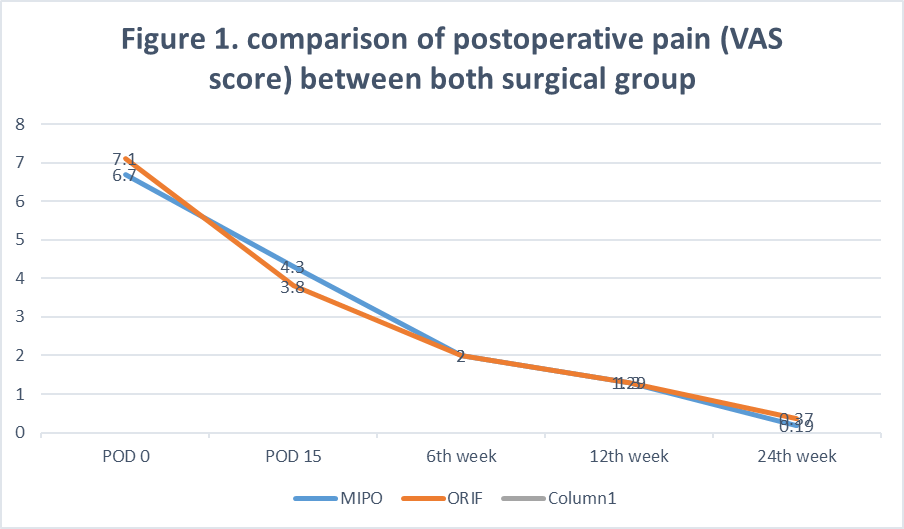

Post-operative pain assessment

On post-operative day 0 (POD 0), all patients in the ORIF group and nearly 90% in the MIPO group reported severe pain. By day 15, about half of the ORIF group and over 90% of the MIPO group experienced severe to moderate pain, with a significant difference (P = 0.004). However, by the 6th, 12th, and 24th weeks, the trend reversed, showing nearly 40% with post-operative pain in the ORIF group and around 20% in the MIPO group at 24 weeks, though this difference was not statistically significant (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Table 2: Incidence of post-operative pain

Figure 1: Comparison of post-operative pain (Visual Analogue Scale Score) between both surgical group.

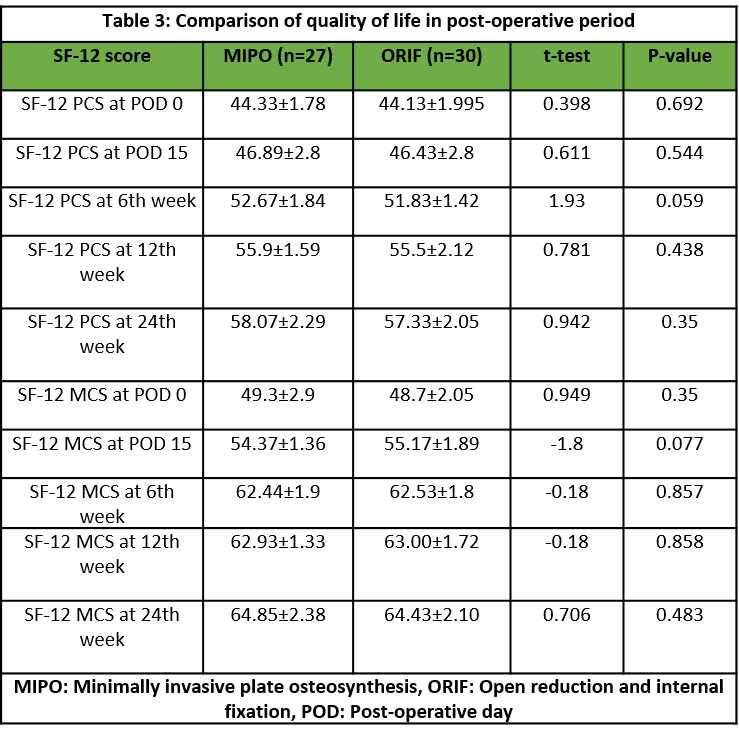

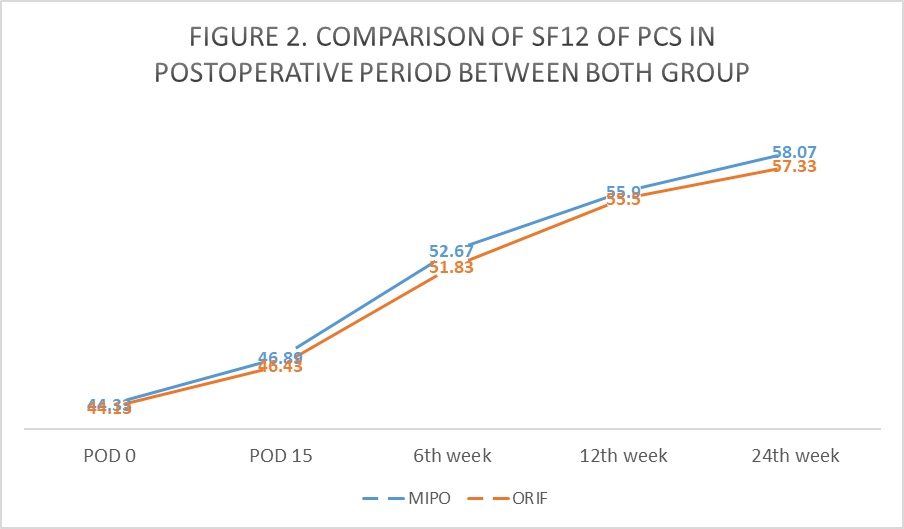

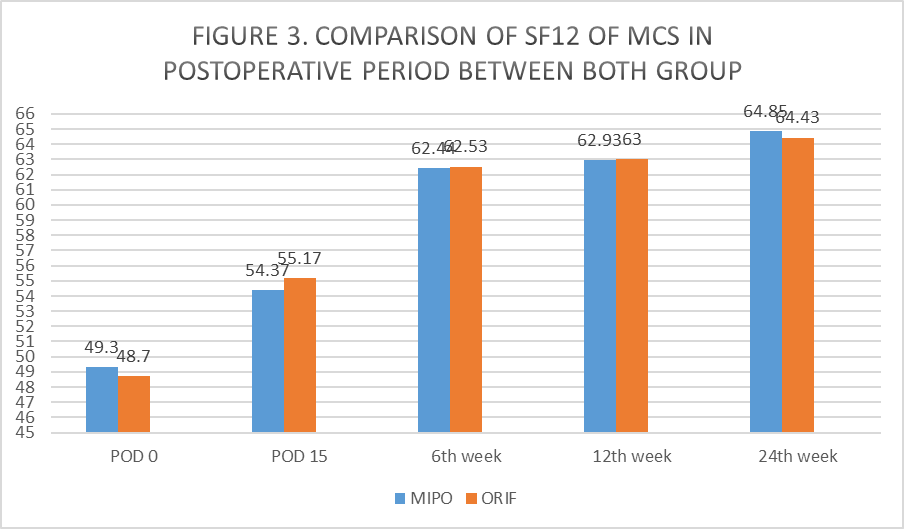

Quality of life assessment

The ORIF group had a lower physical and mental SF-12 score at all post-operative follow-up periods and at POD 0 and the 24th week, though the difference was statistically insignificant (Table 3, Fig. 2 and 3).

Table 3: Comparison of quality of life in post-operative period

Figure 2: Comparison of SF-12 of post-operative pulmonary complications in post-operative period between both groups.

Figure 3: Comparison of SF-12 of mental component summary in post-operative period between both groups.

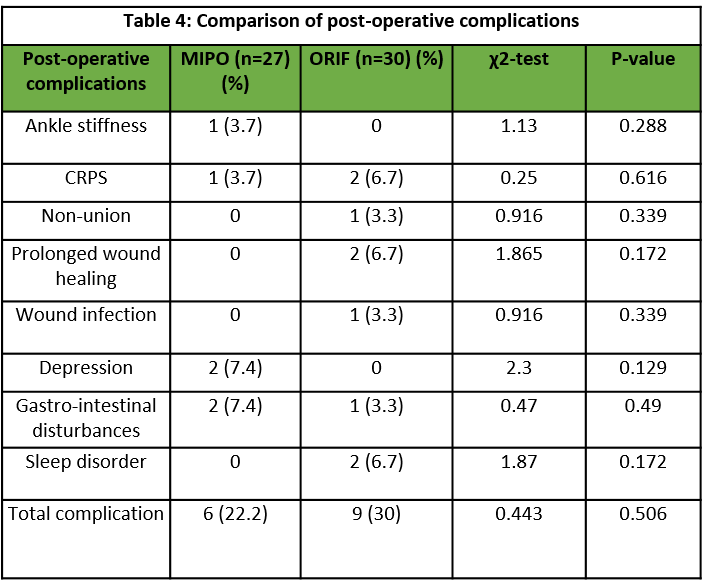

Complications

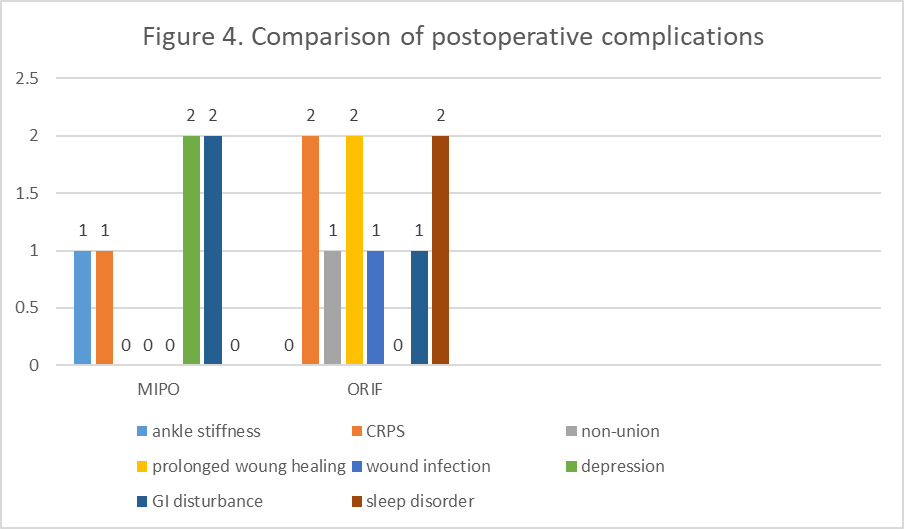

Surgery-related complications such as non-union, prolonged wound healing, and wound infection were more common among the ORIF group, but the difference was insignificant. The total sequelae or complications were lower in the MIPO group (22.2% versus 30%), but not significantly (Table 4 and Fig. 4).

Table 4: Comparison of post-operative complications

Figure 4: Comparison of post-operative complications.

Intra-operative factors

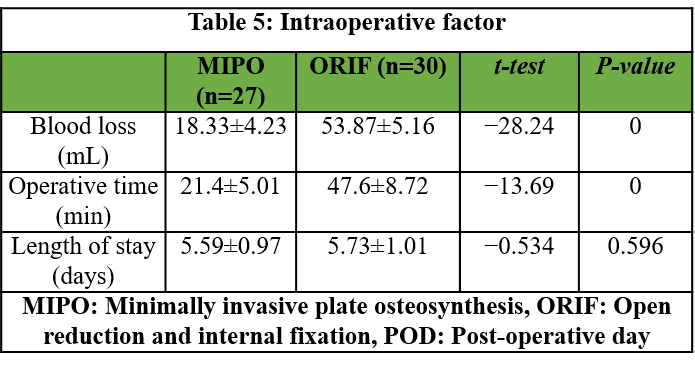

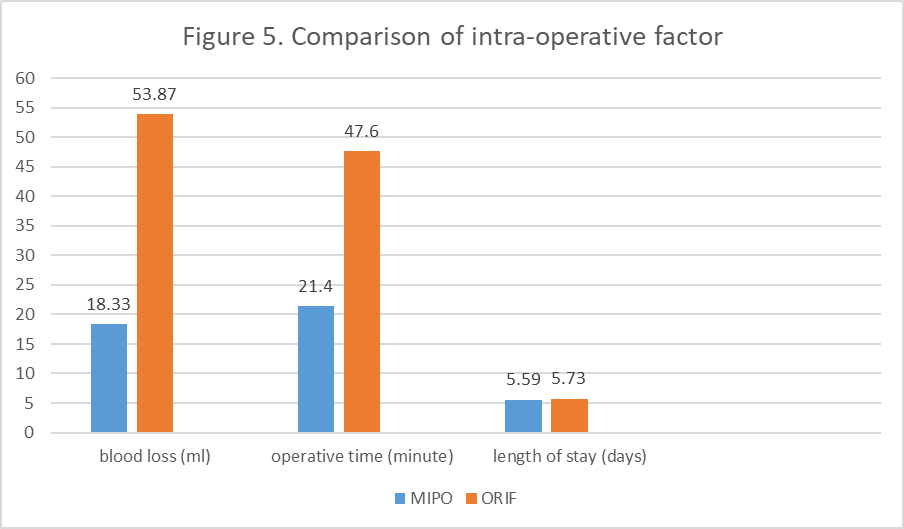

The mean blood loss during operation was higher in the ORIF group- 53.87 ± 5.16 mL versus 18.33 ± 4.23 mL in the MIPO group and statistically significant (P < 0.001). Similarly, the mean operative time was significantly higher among the ORIF group than the MIPO group (47.6 ± 8.72 min versus 21.4 ± 5.01 min, P < 0.001). The duration of hospital stay was also more in the ORIF group compared to the MIPO group (5.73 ± 1.01 days vs. 5.59 ± 0.97 days), though it was not significant (Table 5 and Fig. 5).

Table 5: Intraoperative factor

Figure 5: Comparison of intraoperative factor.

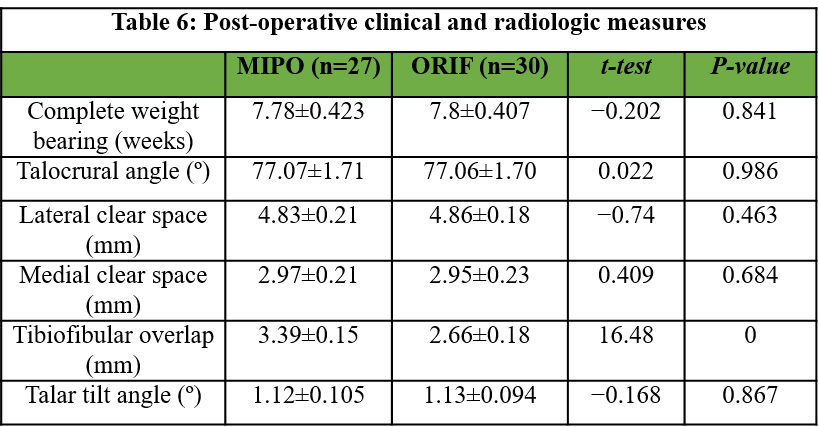

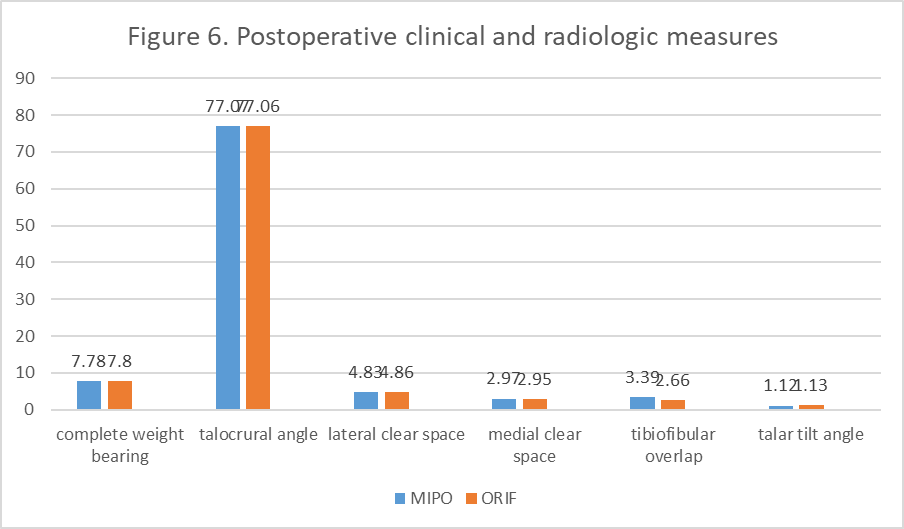

Post-operative clinical and radiologic outcomes

The duration for complete weight bearing was similar among the ORIF and MIPO group (7.8 ± 0.407 weeks vs. 7.78 ± 0.423 weeks). Radiological outcomes such as talocrural angle (77.08 ± 1.70° vs. 77.06 ± 1.71°), lateral clear space (4.86 ± 0.18 mm vs. 4.83 ± 0.21 mm), medial clear space (2.95 ± 0.23 mm vs. 2.97 ± 0.21 mm), and talar tilt angle (1.13±0.094° vs. 1.12 ± 0.105°) were also similar between both (ORIF and MIPO) groups. Only tibiofibular overlap had significant difference between two groups (2.66 ± 0.18 mm vs. 3.39 ± 0.15 mm, P < 0.001) (Table 6 and Fig. 6).

Table 6: Post-operative clinical and radiologic measures

Figure 6: Post-operative clinical and radiologic measures.

The incision for MIPO was significantly smaller than for ORIF (Fig. 7). A representative case of MIPO fixation is shown in pre- and immediate post-operative radiographs (Fig. 8).

Figure 7: Incision of minimally invasive percutaneous plate osteosynthesis versus open.

Figure 8: Pre-operative and immediate post-operative in a patient where minimally invasive percutaneous plate osteosynthesis fixation was done.

The most important finding of the present study was that MIPO was better than ORIF in terms of the overall complication rate (22.2% vs. 30%) in the treatment of distal fibula fractures. Surgery-related complications such as non-union, prolonged wound healing, and wound infection were more common in the ORIF group, but the difference was statistically insignificant. By the 24th week, nearly 40% had post-operative pain in the ORIF group, whereas only around 20% in the MIPO group, though this difference was statistically insignificant. The ORIF group had a lower physical and mental SF-12 score at all post-operative follow-up periods and POD 0 and the 24th week, though the difference was statistically insignificant. Typical wound complications seen in the ORIF group are illustrated in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Wound complications in a patient where open reduction and internal fixation were done.

Time for operation, duration of stay, and intraoperative blood loss were lower in the MIPO group. All radiographic findings after the operation, except for the tibiofibular overlap, were similar in both groups. MIPO maintained biological status in fracture management; it has been successfully employed in various long bone fractures [2,3,7,12,13,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30]. In the open method, wound complications are one of the most common problems. Soft-tissue complications were ranging from 9% to 22% [2,4,7,31]. In older patients, soft-tissue complication is almost 40% [5]. MIPO has decreased the incidence of soft-tissue complications. So far, only a few articles have investigated MIPO in distal fibula fractures. Krenk et al., [3] showed in a case series consisting of 19 complex ankle fractures managed by MIPO did not suffer from any soft-tissue complications while healing. Hess and Sommer showed that MIPO was used in 20 distal fibular injuries complicated with soft-tissue involvement, and 17 recovered without any further complications [6]. Iacobellis et al., showed in their study that the ORIF group had five cases of wound complications compared to none among the MIPO cases [7]. A study done by Marazzi et al., showed the ORIF group had a significantly higher number of complications than in the MIPO group (37% vs. 14%, P = 0.029), and complications of wound healing such as infection, skin necrosis, and non-union, were less in the MIPO group, even though it was not statistically significant [2]. The present study had 57 distal fibular fracture cases, of which 30 were treated with ORIF and 27 were treated with MIPO in a single institution. The findings in the present study were similar to previous studies. Wound-related complications like non-union, prolonged wound healing, and wound infection were more common in the ORIF group. The ORIF group had a higher total complication rate, but the difference was not statistically significant. In a study done by Marazzi et al., 26% of patients in the ORIF group and 17% of patients in the MIPO group suffered from post-operative pain [2]. Brown et al., showed that after ORIF, in a follow-up period averaging 27 months, 31% of patients experienced considerable pain due to the hardware, while 17% had their hardware taken out [32]. In the study, all patients in the ORIF group and approximately 90% of those in the MIPO group mentioned experiencing severe pain on POD 0. By day 15, about half of the ORIF group and over 90% of the MIPO group reported pain that was severe to moderate (P = 0.004). However, at weeks 6, 12, and 24, nearly 40% of the ORIF group continued to experience pain, compared to around 20% in the MIPO group at week 24. This difference in pain levels was not statistically significant. These findings were similar to the previous studies. Marazzi et al., showed that all post-operative radiologic measurements in both the MIPO and ORIF groups were within the normal range, and all post-operative radiologic measurements, except the tibiofibular overlap, were within normal ranges in both groups [2]. These findings were consistent with the present study. The study by Hermans et al., showed that syndesmotic injury did not correspond with tibiofibular overlap. Normal radiologic measurements could include syndesmotic injury, but abnormal radiologic measurements always indicate syndesmotic injury [33]. Nielson et al., showed there was no association between the tibiofibular clear space and overlap measurements on magnetic resonance imaging scans in syndesmotic injury [34]. Sowman et al., showed that only 1.23% of the sample population without any ankle pathology, had no overlap between tibia and fibula [35]. The normal value of the tibiofibular overlap should be greater than or equal to 1 mm [36]. Hence, measurement in both groups in the present study was normal. The present study showed that patients in the MIPO group require lesser duration for complete weight bearing than patients in the ORIF group (7.8 ± 0.407 weeks vs. 7.78 ± 0.423 weeks), but it was not significant. A study done by Iacobellis et al., showed the functional assessment done by Olerud and Molander was 87.4 points in the ORIF group (80–100) and 95.6 in the MIPO group (82–100). The mean intraoperative blood loss was significantly higher among the ORIF group at 53.87 ± 5.16 mL compared to 18.33 ± 4.23 mL among the MIPO group (P < 0.001). The ORIF group also had a longer operative time (47.6 ± 8.72 minutes vs. 21.4 ± 5.01 min, P < 0.001). The duration of hospital stay was higher in the ORIF group (5.73 ± 1.01 days vs. 5.59 ± 0.97 days), but it was not significant. Previous studies showed similar findings [2,7]. The ORIF group had a lower physical and mental SF-12 score at all post-operative follow-up periods and at POD 0 and the 24th week, though the difference was not statistically significant. Brown et al., showed that after ORIF, SF-36 scores at final follow-up were significantly higher for patients with no pain than those with pain overlying their lateral hardware [32]. The main limitation of this study is that it is a retrospective design with a short follow-up of 6 months, which prevents assessment of any long-term functional outcome, complications, and patient-reported complaints. In addition, the small patient number and the mix of fracture severities could confound results, although these fracture types were evenly represented in both groups. The post-operative radiographic comparisons with the opposite side were not done, which is also a limitation of the study. For gathering further evidence, studies with a prospective randomized controlled design with standardized post-operative evaluations and specific functional scores should be conducted.

The present study concluded that the MIPO technique for treating distal fibular fractures was better ORIF in terms of post-operative pain in follow-up, complications, intraoperative blood loss, operative time, hospital stay, post-operative clinical (duration of complete weight bearing), radiological outcome, and quality of life. These findings require further study and discussion to provide more substantial evidence. The results of this study indicate that MIPO may be a better technique compared to ORIF for treating distal fibula fractures. However, this observation should be further investigated to draw more definitive conclusions.

MIPO is a safe and effective technique for treating distal fibula fractures, especially in patients where soft-tissue preservation is a priority. It offers the advantage of shorter operative time, reduced blood loss, and potentially fewer wound complications without compromising fracture alignment or healing. While not universally superior, MIPO represents a valuable option in the orthopedic surgeon’s armamentarium and warrants further consideration in appropriately selected cases.

References

- 1. Michelson JD. Fractures about the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:142-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Marazzi C, Wittauer M, Hirschmann MT, Testa EA. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis (MIPO) versus open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) in the treatment of distal fibula Danis-Weber types B and C fractures. J Orthop Surg Res 2020;15:491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Krenk DE, Molinero KG, Mascarenhas L, Muffly MT, Altman GT. Results of minimally invasive distal fibular plate osteosynthesis. J Trauma 2009;66:570-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Höiness P, Engebretsen L, Strömsöe K. Soft tissue problems in ankle fractures treated surgically. A prospective study of 154 consecutive closed ankle fractures. Injury 2003;34:928-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Wang TJ, Ju WN, Qi BC. Novel management of distal tibial and fibular fractures with Acumed fibular nail and minimally invasive plating osteosynthesis technique: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96:e6482. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Hess F, Sommer C. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis of the distal fibula with the locking compression plate: First experience of 20 cases. J Orthop Trauma 2011;25:110-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Iacobellis C, Chemello C, Zornetta A, Aldegheri R. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis in type B fibular fractures versus open surgery. Musculoskeletal Surg 2013;97:229-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Farouk O, Krettek C, Miclau T, Schandelmaier P, Guy P, Tscherne H. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis and vascularity: Preliminary results of a cadaver injection study. Injury 1997;28 Suppl 1:A7-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Rhinelander FW. The normal microcirculation of diaphyseal cortex and its response to fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1968;50:784-800. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Farouk O, Krettek C, Miclau T, Schandelmaier P, Guy P, Tscherne H. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis: Does percutaneous plating disrupt femoral blood supply less than the traditional technique? J Orthop Trauma 1999;13:401-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Sommer CH, Bereiter H. Aktueller Stellenwert der minimal-invasiven Chirurgie bei der Frakturversorgung [Actual relevance of minimal invasive surgery in fracture treatment]. Ther Umsch 2005;62:145-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Krettek C, Schandelmaier P, Miclau T, Bertram R, Holmes W, Tscherne H. Transarticular joint reconstruction and indirect plate osteosynthesis for complex distal supracondylar femoral fractures. Injury 1997;28 Suppl 1:A31-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Krettek C, Schandelmaier P, Miclau T, Tscherne H. Minimally invasive percutaneous plate osteosynthesis (MIPPO) using the DCS in proximal and distal femoral fractures. Injury 1997;28 Suppl 1:A20-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Wenda K, Runkel M, Degreif J, Rudig L. Minimally invasive plate fixation in femoral shaft fractures. Injury 1997;28 Suppl 1:A13-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg 2014;12:1495-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Fracture and dislocation compendium. Orthopaedic trauma association committee for coding and classification. J Orthop Trauma 1996;10 Suppl 1:v-ix, 1-154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Marsh JL, Slongo TF, Agel J, Broderick JS, Creevey W, DeCoster TA, et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium – 2007: Orthopaedic trauma association classification, database and outcomes committee. J Orthop Trauma 2007;21 10 Suppl:S1-133. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Available from: https://www.sira.nsw.gov.au/resources-library/motor-accident-resources/publications/for-professionals/whiplash-resources/sira08110-1117-396462.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Jan 06]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Available from: https://www.hoagorthopedicinstitute.com/documents/content/SF12form.pdf [Last accessed on 2023 Jan 06]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Buckley RE, Moran CG, Apivatthakakul T. AO Principles of Fracture Management. Switzerland: Foundation AO; 2017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA), Office of Device Evaluation. Guidance Document for Industry and CDRH Staff for the Preparation of Investigational Device Exemptions and Premarket Approval Application for Bone Growth Stimulator Devices. United States: United States Food and Drug; 1988 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Lau TW, Leung F, Chan CF, Chow SP. Wound complication of minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis in distal tibia fractures. Int Orthop 2008;32:697-703. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Helfet DL, Shonnard PY, Levine D, Borrelli J Jr. Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis of distal fractures of the tibia. Injury 1997;28 Suppl 1:A42-7; discussion A7-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Schandelmaier P, Partenheimer A, Koenemann B, Grun OA, Krettek C. Distal femoral fractures and LISS stabilization. Injury 2001;32 Suppl 3:SC55-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Collinge C, Protzman R. Outcomes of minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis for metaphyseal distal tibia fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2010;24:24-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Gupta RK, Rohilla RK, Sangwan K, Singh V, Walia S. Locking plate fixation in distal metaphyseal tibial fractures: Series of 79 patients. Int Orthop 2010;34:1285-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Redfern DJ, Syed SU, Davies SJ. Fractures of the distal tibia: Minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis. Injury 2004;35:615-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Zou J, Zhang W, Zhang CQ. Comparison of minimally invasive percutaneous plate osteosynthesis with open reduction and internal fixation for treatment of extra-articular distal tibia fractures. Injury 2013;44:1102-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Gülabi D, Bekler Hİ, Sağlam F, Taşdemir Z, Çeçen GS, Elmalı N. Surgical treatment of distal tibia fractures: Open versus MIPO. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg 2016;22:52-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Sohn HS, Kim WJ, Shon MS. Comparison between open plating versus minimally invasive plate osteosynthesis for acute displaced clavicular shaft fractures. Injury 2015;46:1577-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Schepers T, Van Lieshout EM, De Vries MR, Van der Elst M. Increased rates of wound complications with locking plates in distal fibular fractures. Injury 2011;42:1125-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Brown OL, Dirschl DR, Obremskey WT. Incidence of hardware-related pain and its effect on functional outcomes after open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2001;15:271-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Hermans JJ, Wentink N, Beumer A, Hop WC, Heijboer MP, Moonen AF, et al. Correlation between radiological assessment of acute ankle fractures and syndesmotic injury on MRI. Skeletal Radiol 2012;41:787-801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 34. Nielson JH, Gardner MJ, Peterson MG, Sallis JG, Potter HG, Helfet DL, et al. Radiographic measurements do not predict syndesmotic injury in ankle fractures: An MRI study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;436:216-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 35. Sowman B, Radic R, Kuster M, Yates P, Breidiel B, Karamfilef S. Distal tibiofibular radiological overlap: Does it always exist? Bone Joint Res 2012;1:20-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 36. Southerland JT. McGlamry’s Comprehensive Textbook of Foot and Ankle Surgery. 4th ed. United States: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]