The article explores the relationship between spinopelvic parameters (SPPs) in patients with disc degeneration without listhesis and those with degenerative spondylolisthesis (DSL), aiming to uncover how disc degeneration may contribute to the development of listhesis.

Dr. Mantu Jain, Department of Orthopedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: montu_jn@yahoo.com

Introduction: The natural history of degenerative disc disease (DDD) has been the subject of intense study over the last several decades. Although many authors have observed that the degenerated motion segment undergoes progressive reduction of mobility in all directions, in some instances, the degeneration progresses to a sagittal plane segmental displacement (degenerative listhesis). The aim of the study is to compare the spinopelvic parameters (SPPs) between patients with degenerated disc but no listhesis versus those who have a degenerative spondylolisthesis (DSL). We also attempt to statistically correlate and thereby predict which patients are likely to progress to DSL.

Materials and Methods: Between September 2021 and August 2024, 63 patients with a single-level degenerative pathology at L4-5 level were divided into DSL and non-listhesis group. Their SPPs, namely pelvic incidence (PI), pelvic tilt (PT), sacral slope (SS), lumbar lordosis (LL), disc angle, and position of L5 were studied on standing lumbosacral spine X-ray. The variables were compared between groups, receiver operator characteristic and cut-off points were calculated, and a multiple logistic regression was performed.

Results: 52 patients were available for final analysis. DSL groups had higher PI and PT as well as lower disc angle in comparison to non-listhetic patients. A PI of >48.8°, PT of > 16.75°, and a disc angle of >−8.05° (implying a more kyphotic segment) were deemed threshold values for predicting DSL. The logistic regression yielded an adjusted odds ratio of 1.127 (PI) and 1.299 (disc angle), respectively.

Conclusion: High PI with pelvic retroflexion and normal LL seem to be the prerequisites for DSL developing at a degenerative disc at the L4-5 level. Thus, Roussouly Type 3 Spino-pelvic alignment individuals seem most predisposed to develop DSL.

Keywords: Degenerative disc disease, degenerative spondylolisthesis, spino-pelvic parameters, disc angle, correlation.

The natural history of degenerative disc disease (DDD) has been the subject of intense debate over the past several decades. The Kirkaldy Willis and Farfan model forms the very foundation of our understanding; they suggest that DDD ultimately affects all elements of the 3 joint complex and progresses through dysfunction and instability sequences ending in spontaneous stabilization of the motion segment [1]. Although it is observed that the degenerated motion segment undergoes progressive reduction in mobility about all directions [2], we also find that in some instances, the disc degeneration progresses to a sagittal plane segmental displacement (degenerative listhesis) [3]. Junghanns (1930) is credited with the first report of this listhesis without pars defect [4], while MacNab (1950) labeled it pseudo-spondylolisthesis [5]. It was Newman (1955) who related this to DDD and coined the term degenerative spondylolisthesis (DSL) [6]. Typically, DSL is most frequently seen in women of over 50 years and involves the L4-5 segments and is often asymptomatic [7]. The exact prevalence of the DSL is unknown.

Pope et al. suggested the phrase “segmental instability,” defined as loss of stiffness of the motion segment leading to pain, deformity, and potential neural tissue compromise [8]. The very definition of segmental instability as a clinical and radiological entity is controversial, largely because the precise criteria for the diagnosis (or the range of normal segmental mobility) have not been well defined. But assuming that DSL is a single entity with linear progression, why do some disc degenerations progress to cause listhesis while others do not. Over the last decade, there have been a number of studies on spino-pelvic parameters (SPPs) and their putative role in DSL and degenerative scoliosis (DS). Some studies have particularly emphasized the significant role of global sagittal spinal alignment in the development of spondylolisthesis in a degenerate disc [9,10,11,12,13]. We hypothesize that the spatial relationship between the pelvis and the L4 vertebra in the sagittal plane is what determines the propensity of the L4 vertebra to slide over its neighbor once the constraints of the disk are lost due to degeneration. The L5 remains fixed to the pelvis due to the normal or degenerate, yet stable disc at L5-S1. In this retrospective observational study, the authors attempt to relate listhesis to the SPPs. Therefore, the study is designed to compare the SPPs between the cohorts of patients who have degenerated disc with no listhesis vs. those who have a DSL. We also attempt to statistically correlate the various SPPs that contribute to DSL and predict which patients are likely to progress to such a state.

This is a retrospective study of 63 consecutive adult patients who underwent surgery for lumbar DDD at the primary investigator’s (NT) center between September 2021 and August 2024. Two pathologies were included in the study: Group 1 included patients who had symptomatic DSL and group 2 included patients who had reduced disc space due to DDD presenting with stenosis (central/foraminal), but no listhesis. Patients over the age of 45 years and a single level involvement at L4-5 were included in the study (the L4-5 level was chosen largely because that was the most common level where degenerative listhesis occurred). Patients with more than one level or level other than L4-5 or pathology other than DDD were excluded from our study. The threshold of slip to define DSL was set at grade 1-2 Meyerding’s grade. SPPs were measured on pre-operative spine standing lumbosacral radiographs available from the records. These were measured as per the description in literature [14].

- Pelvic incidence (PI): The angle between the perpendicular to the sacral plate and the line connecting the midpoint of the sacral plate to the bi-coxo-femoral axis

- Sacral slope (SS) corresponds to the angle between the sacral endplate and the horizontal plane

- Pelvic tilt (PT) corresponds to the angle between the line connecting the midpoint of the upper sacral endplate to the bi-coxo-femoral axis and the vertical plane

- Lumbar lordosis (LL) – the angle from the sacral endplate to the upper endplate of L1 vertebral body

- PI-LL – the difference between the PI and LL

- Disc angle – The angle between the lower end plate of L4 and upper end plate of L5 on standing X-ray.

- L5 station – based on a line joining the highest points of both iliac crests (inter-cristal line) and the superior end plate of L5. The station of L5 can be of three types (type I to III) [15].

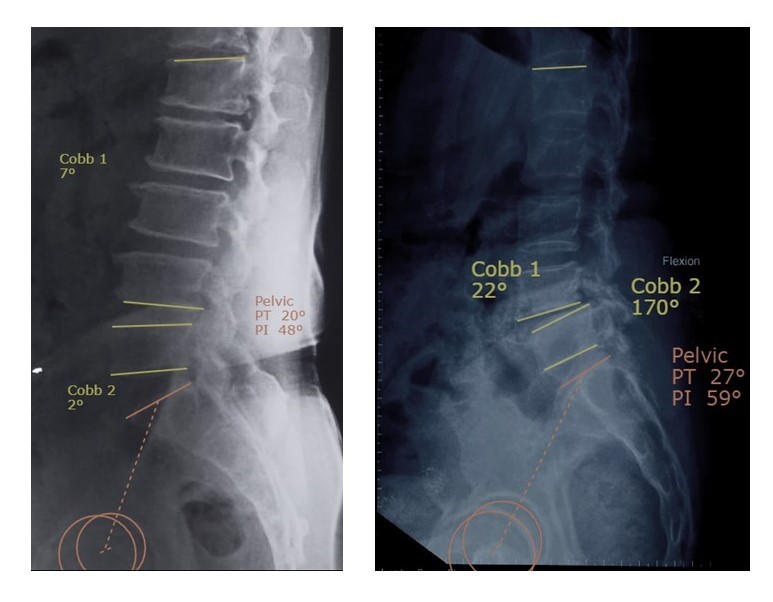

After scanning the lateral radiographs, Surgimap spine software was used to draw all the above-mentioned independent variables. The Surgimap Spine is a free computer program (http://www.surgimap.com; Nemaris Inc., New York, NY, USA) that integrates the spine‑related measurements and tools for surgical planning in combination with knowledge gained from the published literature. After importing preoperative digital radiographs into a Surgimap Spine customizable database, measurements and alignment planning were executed. The software program calculates angles in degrees. Fig. 1 is an illustration of various angles measured by the surgical software.

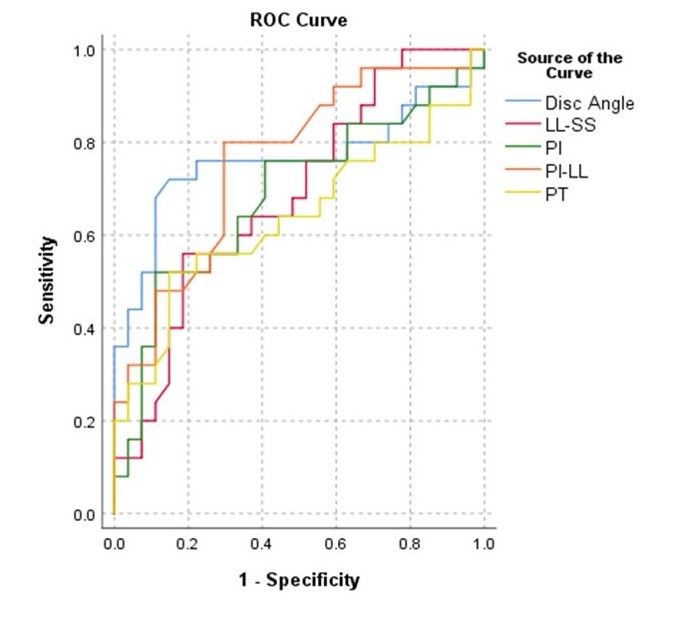

Figure 1: Combined receiver operator characteristic curve of the significant variables.

Statistical analysis

The data analyses were done using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26. The continuous variables such as age and SPPs were represented as mean ± standard deviation and analyzed using the student t-test. The categorical variables were expressed as proportion and analyzed using the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. Those that were statistically significant were further plotted with receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curve and the cut-off values for DSL were calculated including their sensitivities and specificities. Further, multiple logistic regression model was used to predict the influence of the various SPPs on DSL. The statistical level of significance was set at 0.05.

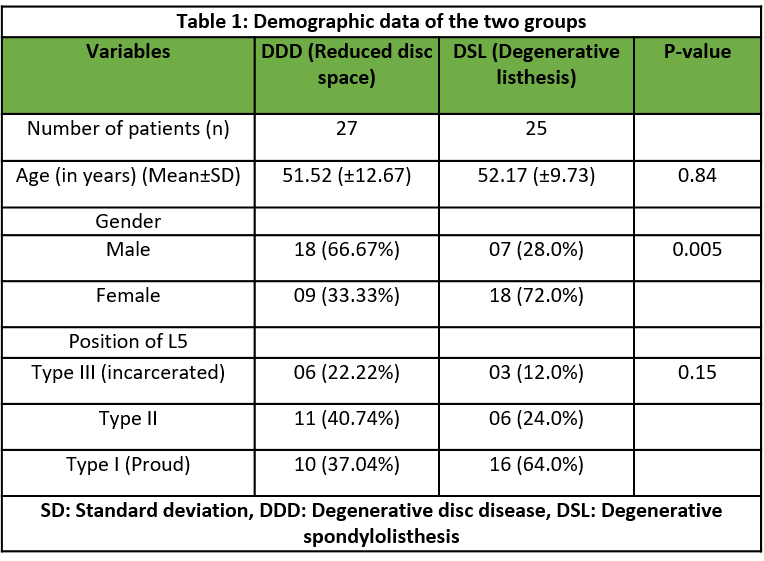

After excluding patients with missing data, a total of 52 patients were analyzed with 25 in group 1 and 27 in group 2. There were more females in group 1 as compared to group 2. Otherwise, they were quite similar in terms of age and station of L5 (Table 1).

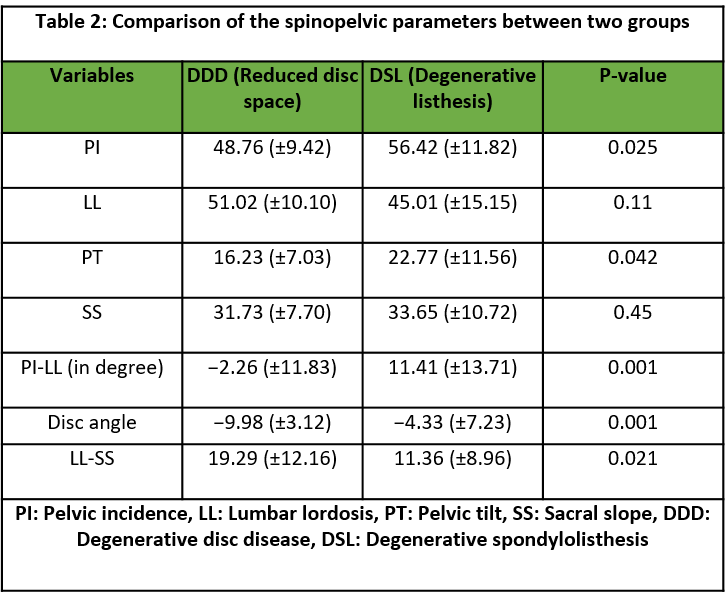

We find that there was a considerable difference among the SPPs between the groups as seen in Table 2.

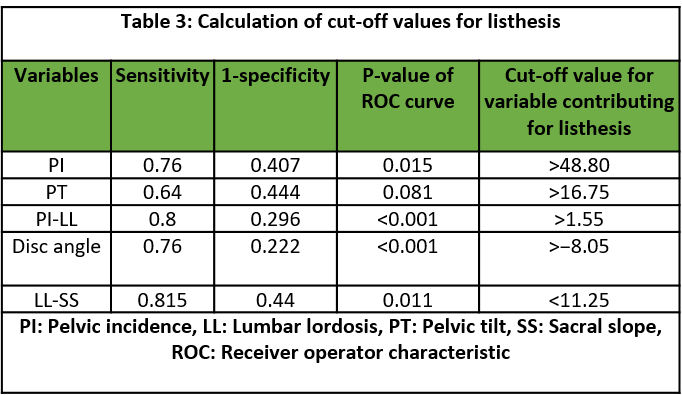

The variables in SPPs that were statistically significant were further evaluated for ROC analysis and the cut-off for SPLs was calculated as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

The variables in SPPs that were statistically significant were further evaluated for ROC analysis and the cut-off for SPLs was calculated as shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1.

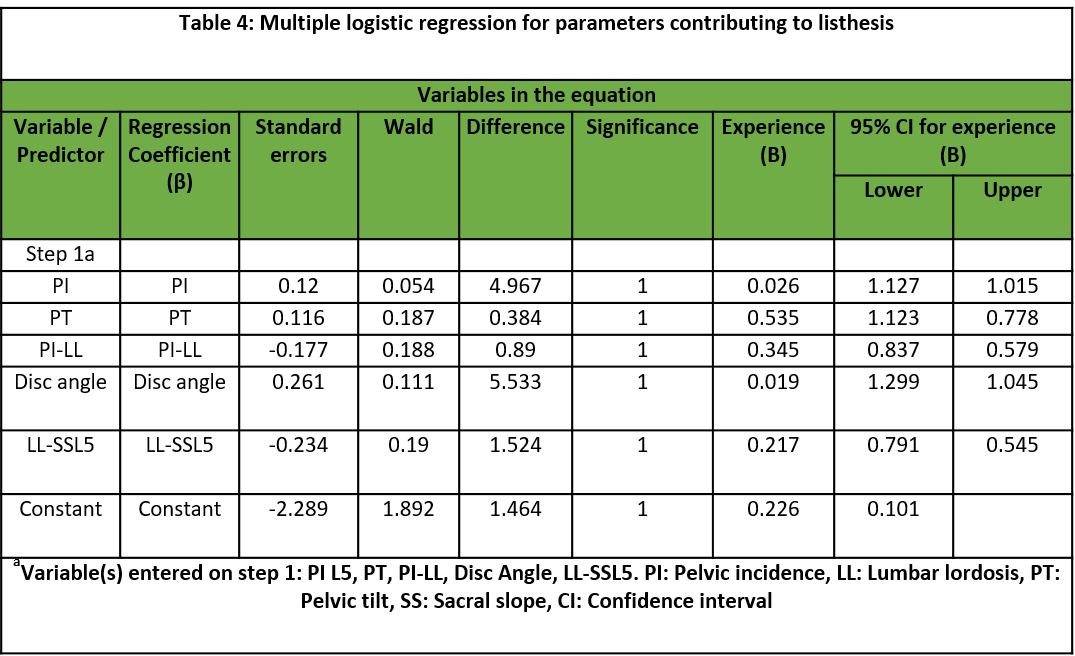

Finally, the variables of SPPs were analyzed with multiple logistic regression model and the coefficients were derived as depicted in Table 4.

Finally, the variables of SPPs were analyzed with multiple logistic regression model and the coefficients were derived as depicted in Table 4.

This table of multivariate logistic regression shows that the PI and disc angle have a significant impact on the outcome with adjusted odds ratio of 1.127 and 1.299, respectively. This means that the DSL group has a significantly higher value of PI and disc angle than DDD Group. A representative case and its graphical representation are given in Fig. 2 and 3.

This table of multivariate logistic regression shows that the PI and disc angle have a significant impact on the outcome with adjusted odds ratio of 1.127 and 1.299, respectively. This means that the DSL group has a significantly higher value of PI and disc angle than DDD Group. A representative case and its graphical representation are given in Fig. 2 and 3.

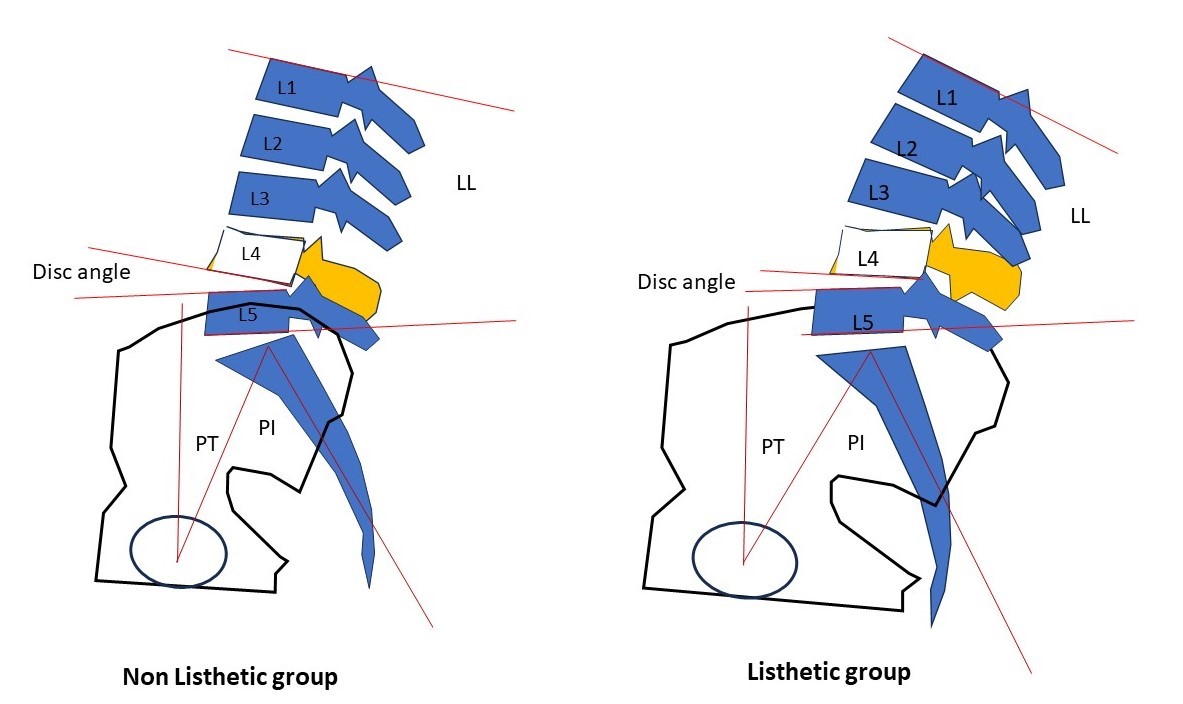

Figure 2: Case illustration of non-listhesis patient and listhetic group patient.

Figure 3 &4: Diagrammatic representation of our findings in the two groups with parameters.

This study compares 2 groups of patients who underwent surgery for single-level DDD of the lumbar spine at L4-5 level – a group without and with DSL of the affected segment. There were 3 salient observations in the study population – the PI in the DSL group is significantly higher than the control group. Similarly, the PT is also higher in the DSL patients. Segmental disc angle measured at the L4-5 (slip level) is almost always less lordotic in the DSL group compared to the non-listhetic group (Fig. 4). ROC curves were used to study the cut-off values of each of the 3 statistically significant parameters. A PI of >48.8° was found to be predictive of DSL, while a PT of >16.75° and a disc angle of >−8.05° (implying more segmental kyphosis) were deemed threshold values for predicting DSL. The study also observed that total LL does not vary significantly between the groups and therefore cannot be used as a predictor of DSL. Since the total LL is similar in both cohorts and the segmental lordosis significantly different, there must be a compensatory change above or below the L4-5 level; L5-S1 being relatively fixed, one might assume that maximum difference in the sagittal plane is between L1 and L4 end plates. Another interesting observation is related to the station (position) of the L5 in relation to the pelvis. Patgaonkar et al. classified the L5 position into 3 locations depending on the relationship of the inferior border of L5 vertebra to the intercristal line [15]. These authors use the terms fully incarcerated, partially incarcerated, and standing proud for the 3 levels described. It was assumed that the location of L5 might influence the mobility of the L4-5 motion segment and therefore in some manner predispose to DSL. Such was not the case based on this study, i.e., all 3 variations in L5 station seemed to have equal predilection to develop DSL. DSL primarily occurs at the L4-L5 level. In their landmark study, Gille et al., found that the slippage was located at L5-S1 in 6% of cases, L4-L5 in 73%, L3-L4 in 18%, and L2-L3 in 3%; 12% of patients had slippage at two or more levels [16]. Researchers have attributed the etiology of DSL to several factors such as pregnancy, generalized joint laxity, and oophorectomy, mainly due to its preponderance in women [17,18,19]. Sengupta and Herkowitz observed that sagittal orientation of the facet joints and increased pedicle-facet angle as predisposing factors [3]. In yet another study, Rothman et al., reported that forward subluxation is primarily a disease of the posterior joints and is found most commonly at L4–L5, whereas retrolisthesis is a primary disorder of the disc space and is noted more commonly at L3–L4. However, the exact etiology of DSL still remains elusive [20]. A number of papers have also appeared studying the influence of SPPs on DSL. The French Spine Society published their study of DSL in 2014 and 2017, describing 3 categories of degenerative slips based on the spino-pelvic alignment [16,17,18,19,20,21]. These authors described a small number of patients with <25° of PT while a much larger number had >25° of PT. Both groups had large PIs (and PI-LL >10°). In their study, a significant number of patients had sagittal vertical axis (SVA) >40 mm, suggesting gross sagittal malalignment. This was not measured in any of the patients in our cohort but it is assumed that the difference in ages of the samples was the cause of the difference; our patients were much younger than the French study. It appears that nearly all our cases fit into the Type 1B described by these authors (segmental lordosis altered but LL preserved). The authors of the French study had only 3/166 patients in this subgroup while all our patients seemed to fit in this category. However, our patients were not analyzed for global sagittal parameters and these observations are only based on regional parameters. The threshold value for PT has been 25° in the French study (above which the authors call the slip a type 2B). Barrey et al., demonstrated a significant greater PI in patients with DSL than the normal population, suggesting that the shape of the pelvis is a main predisposing factor for DSL [11]. They reported 60° of PI in their study with DSL while our threshold was 49°. Interestingly, these authors propose that the higher PI is associated with higher LL and SS which in turn predisposes to the slip due to gravity. Other studies, including our own, have not been able to show that DSL cases are associated with higher LL and SS. In our study, the DSL cohort had loss of lordosis, tendency to anterior sagittal unbalance, and less SS, reflecting the pelvis back tilt of these patients. Similarly, Morel et al., also established that DSL patients demonstrated a significantly higher PI (62.6°), a loss of LL, and a decrease in SS [22]. Recently, Fei Han et al., conducted a study of the SSPs in patients with lumbar DS [23]. Interestingly, these authors also found a high PI in patients with DS but the PI was even higher in patients with associated DLS than those without. They attributed this high PI to the high prevalence of DLS among DS patients. Kobayashi et al., study also identified large PI as one of the risk factors for the SVA deterioration of DSL. Clearly, the evidence thus far suggests that PI may be involved in the onset and progression of DSL [10]. The present authors found that PI and PT were significantly larger and LL and SS were significantly smaller in the DSL group than in the Control group. Borkar et al., published the SPPs in the normal and pathological states in Indian population [13]. These authors found PI in the asymptomatic individuals was 49.29° ± 5.95°, which was significantly lower when compared P < 0.001) to DSL patients (59.4° ± 21.33°, P < 0.001), and failed back surgery syndrome (56.7° ± 8.21°, P < 0.001). The mean PT in healthy controls was 14.3° ± 4.08° which was significantly lower when compared with patients of lumbar listhesis (23.35° ± 14.03°, P < 0.001) and failed back surgery syndrome (22.8° ± 8.09°, P < 0.001), whereas SS and SVA offset did not show any statistically significant difference. Our data also substantiates these results. In the Borkar et al., study, the mean LL measured in healthy individuals was 42.5° ± 7.89°, which was significantly lower than patients with lumbar listhesis (46.24° ± 19.24°, P = 0.04) [13]. Barrey et al., also observed that >85% of DSL cases belonged to Roussouly and Pinheiro-Franco spino-pelvic morphotypes 3 and 4, which is perhaps self-evident because the latter types are associated with high PI values [11,24]. However, Roussouly 4 is typically associated with high SS and LL and low PT which has been contrary to our study findings where the mean SS was 33.65° and the mean LL was 45.01° in the DSL group. Although our study did not explicitly look at the Roussouly types, it is evident that most of our cases would belong to the Type 3 variant (rather than type 4). What then is the value of analyzing these sagittal pelvic parameters in DSL? One is of-course to determine the etiological association of spino-pelvic measures and DSL. In addition, many authors have also shown that restoring the sagittal alignment (particularly PT) can result in better clinical outcomes in DSL [25,26,27,28]. Evidently, individuals with higher PI seem to have a greater propensity to develop listhesis compared to their lower PI counterparts in the event of L4-5-disc degeneration. This seems to match the observations of several authors like Barrey et al., Morel et al., Sun et al., Gille et al., Kobayashi et al., etc., [10,11,21,22,28]. The current study also demonstrates increased PT (and lesser SS), implying a pelvic retroflexion in most cases of DSL. Barrey et al., also describe this loss of LL and the anterior shift of the C7 plumb line. Indeed, Gille’s study does describe a subgroup of patients with normal PT (Type 2A – PT <25), though the numbers of this subtype in their series were small. Moreover, their study describes a fairly large number of patients with preserved segmental lordosis (the authors do not describe how this parameter was measured). The major observation in the current study is the occurrence of reduced disc space lordosis at the L4-5 level while the total LL measured between L1 and S1 remains unaltered compared to controls. The threshold value has been determined to be −4.3° meaning that if the segmental lordosis at L4-5 in a degenerate disc is below this value, it acts as a protection against listhesis at that segment. The authors do agree that it is possible that this segmental disc angle at the L4-5 is likely an effect rather than the cause of the listhesis. This study has certain unique features – firstly, all the patients were operated cases in whom adequate non-operative treatment was tried and they remained sufficiently symptomatic to warrant surgery. Although this study did not have asymptomatic controls, the data suggest that SPPs could have a bearing on symptomatic DDD and symptomatic DSL. The other major advantages of this study are that it is the only study thus far that compares DSL patients with L4-5 degenerative patients without listhesis. Most available literature compares them with normal volunteers. This renders the study the ability to differentiate the precipitating cause of listhesis in a L4-5 degenerated individual and to determine whether it is indeed related to the sagittal pelvic parameters as postulated. This study also has certain limitations. First, it is a retrospective study and the numbers are rather small. The study does not look at outcomes in relation to the variables observed. The X-rays used were standing lateral views of the lumbar spine and the pelvis. Whole spine lateral images and EOS were not available to the authors for the study. Other SPPs notably SVA and coronal spine parameters were not measured in our study. Similarly, facet orientation and degeneration which also might play an important role in DSL were not taken into consideration in our study. While this may have a confounding impact on the study results it is not something that can be addressed in a retrospective study of this nature since CT scans are not routinely performed at our center in DSL cases. Global sagittal plane measurements like SVA and T1-Pelvic angle were not studied in this submission.

High PI with pelvic retroflexion and normal LL seem to be the prerequisites for listhesis developing at a degenerative disc at the L4-5 level. Thus, it is inferred that Roussouly Type 3 Spino-pelvic alignment individuals seem most predisposed to develop DSL.

High pelvic incidence, pelvic retroflexion, and normal lumbar lordosis seem to be prerequisites for L4-5 degenerative disc listhesis. It appears that Roussouly Type 3 Spino-pelvic alignment individuals are most prone to DSL.

References

- 1. Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Farfan HF. Instability of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982;165:110-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Galbusera F, Van Rijsbergen M, Ito K, Huyghe JM, Brayda-Bruno M, Wilke HJ. Ageing and degenerative changes of the intervertebral disc and their impact on spinal flexibility. Eur Spine J 2014;23 Suppl 3:S324-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Sengupta DK, Herkowitz HN. Degenerative spondylolisthesis: Review of current trends and controversies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(Suppl 6):S71-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Junghanns H. Spondylolisthesis without a break in the vertebral pedicles (pseudospondylolisthesis). Arch Orthop Unfall chir 1930;29:118-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Macnab I. Spondylolisthesis with an intact neural arch; the so-called pseudo-spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1950;32:325-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Newman PH. Spondylolisthesis, its cause and effect. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1955;16:305-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Rosenberg NJ. Degenerative spondylolisthesis. Predisposing factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1975;57:467-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Pope MH, Panjabi M. Biomechanical definitions of spinal instability. Spine 1985;10:255-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Soydan Z, Bayramoglu E, Sen C. Elucidation of effect of spinopelvic parameters in degenerative disc disease. Neurochirurgie 2023;69:101388. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Kobayashi H, Endo K, Sawaji Y, Matsuoka Y, Nishimura H, Murata K, et al. Global sagittal spinal alignment in patients with degenerative low-grade lumbar spondylolisthesis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2019;27 (3):2309499019885190. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Barrey C, Jund J, Noseda O, Roussouly P. Sagittal balance of the pelvis-spine complex and lumbar degenerative diseases. A comparative study about 85 cases. Eur Spine J 2007;16:1459-67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Wang Q, Sun CT. Characteristics and correlation analysis of spino-pelvic sagittal parameters in elderly patients with lumbar degenerative disease. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:127. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Borkar SA, Sharma R, Mansoori N, Sinha S, Kale SS. Spinopelvic parameters in patients with lumbar degenerative disc disease, spondylolisthesis, and failed back syndrome: Comparison vis-á-vis normal asymptomatic population and treatment implications. J Craniovertebr Junction Spine 2019;10:167-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Lim JK, Kim SM. Comparison of sagittal spinopelvic alignment between lumbar degenerative spondylolisthesis and degenerative spinal stenosis. J Korean Neurosurg Soc 2014;55:331-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Patgaonkar P, Datar G, Agrawal U, Palanikumar C, Agrawal A, Goyal V, et al. Suprailiac versus transiliac approach in transforaminal endoscopic discectomy at L5-S1: A new surgical classification of l5-iliac crest relationship and guidelines for approach. J Spine Surg 2020;6:S145-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Gille O, Challier V, Parent H, Cavagna R, Poignard A, Faline A, et al. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis: Cohort of 670 patients, and proposal of a new classification. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2014;100:S311-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Imada K, Matsui H, Tsuji H. Oophorectomy predisposes to degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1995;77:126-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Sanderson P, Fraser R. The influence of pregnancy on the development of degenerative spondylolisthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:951-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Morizono Y, Masuda A, Demirtas AM. Natural history of degenerative spondylolisthesis. Pathogenesis and natural course of the slippage. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1990;15:1204-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Rothman SL, Glenn WV Jr., Kerber CW. Multiplanar CT in the evaluation of degenerative spondylolisthesis. A review of 150 cases. Comput Radiol 1985;9:223-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Gille O, Bouloussa H, Mazas S, Vergari C, Challier V, Vital JM, et al. A new classification system for degenerative spondylolisthesis of the lumbar spine. Eur Spine J 2017;26:3096-105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Morel E, Ilharreborde B, Lenoir T, Hoffmann E, Vialle R, Rillardon L, Guigui P. Analyse de l’équilibre sagittal du rachis dans les spondylolisthésis dégénératifs [Sagittal balance of the spine and degenerative spondylolisthesis]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2005;91(7):615-26.. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Han F, Weishi L, Zhuoran S, Qingwei M, Zhongqiang C. Sagittal plane analysis of the spine and pelvis in degenerative lumbar scoliosis. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2017;25(1):2309499016684746 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Roussouly P, Pinheiro-Franco JL. Biomechanical analysis of the spino-pelvic organization and adaptation in pathology. Eur Spine J 2011;20(Suppl 5):609-18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Kim MK, Lee SH, Kim ES, Eoh W, Chung SS, Lee CS. The impact of sagittal balance on clinical results after posterior interbody fusion for patients with degenerative spondylolisthesis: A Pilot study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. He S, Zhang Y, Ji W, Liu H, He F, Chen A, et al. Analysis of spinopelvic sagittal balance and persistent low back pain (PLBP) for degenerative spondylolisthesis (DS) following posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF). Pain Res Manag 2020;2020:597159717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Lenz M, Oikonomidis S, Hartwig R, Gramse R, Meyer C, Scheyerer MJ, et al. Clinical outcome after lumbar spinal fusion surgery in degenerative spondylolisthesis: A 3-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2022;142:721-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Sun XY, Zhang XN, Hai Y. Optimum pelvic incidence minus lumbar lordosis value after operation for patients with adult degenerative scoliosis. Spine J 2017;17:983-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]