The varied terminologies used to describe a spinal procedure are a lot of times confusing to understand. This article provides clarity on the understanding and exact meaning of these terms and in which conditions they should be appropriately used.

Dr Bhushan B. Patil, Department of Orthopedics, D.Y Patil Medical College, Hospital and Research Centre, Pimpri, Pune, Maharashtra, India – 411018 Email: bhushancric@gmail.com

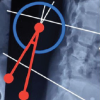

The terms stabilization, fixation, fusion, and reconstruction are frequently used interchangeably amongst spine surgeons. This many times leads to confusion among younger orthopedic, neurosurgeons, and spine surgeons and the multidisciplinary team working along with the spine surgeons. In this editorial, we have tried to analyze and understand this problem by explaining the exact meaning of these terms and where they should be appropriately used (Fig. 1).

Fixation is the mechanical anchorage of the spine with instrumentation to maintain alignment in the face of a potentially destabilizing event, such as a stable fracture with preserved anterior column. Its goal is to immobilize the motion segment and act as a form of primary restraint by creating a scaffold framework that maintains stability until healing occurs. This is achieved using pedicle screws, hooks, sublaminar wires or cables linked by rods and connectors, where bone graft is primarily not used (Fig. 1)

Figure 1: (a) Posterior spinal fixation, (b) Spinal Fusion (interbody), (c) Spinal fixation with fusion, (d) Anteroposterior image demonstrating interbody fusion between the vertebral bodies and posterolateral fusion across the transverse processes.

In fixation, the integrity of the motion segment structures (facet capsules, intervertebral disc, and pars interarticularis) must be preserved during the index surgery, allowing for the possibility of implant removal on subsequent healing.

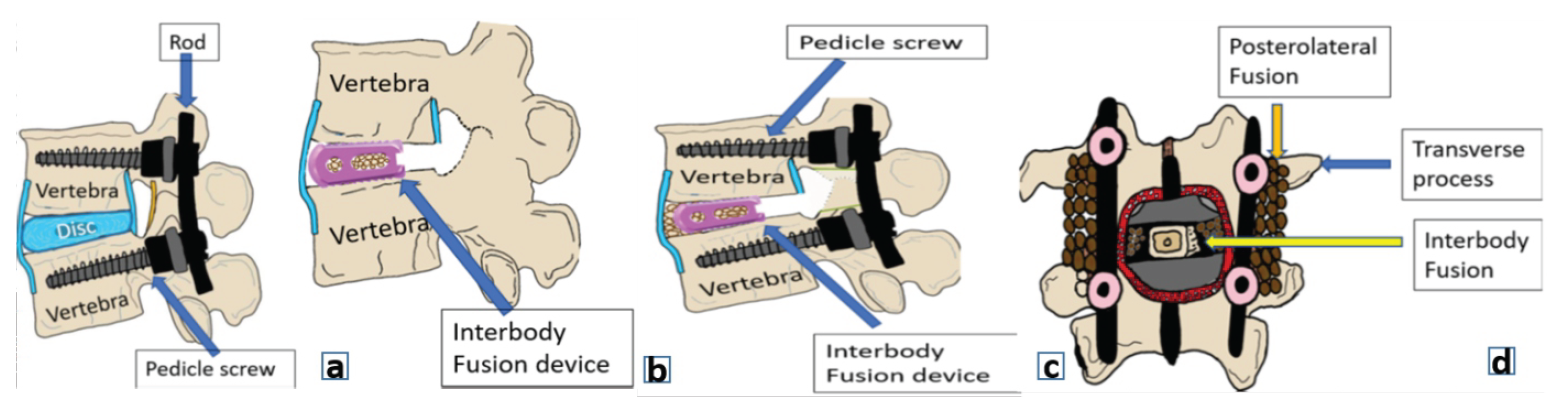

Few examples of spinal fixation include minimally invasive surgery (MIS) fixation in osteoporotic fracture spine, where the aim is to provide a long construct to maintain the alignment of the spinal column (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Post-operative radiograph (a) Anteroposterior and (b) Lateral view showing posterior pedicle screw fixation in an osteoporotic fracture spine. (c) Clinical image demonstrating minimally invasive screw fixation in an osteoporotic spine.

Anterior odontoid screw fixation also falls under the purview of spinal fixation. We aim for fracture union (fibrous or bony) with an anterior odontoid screw to reduce the risk of non-union and persistent neck pain in a stable spine setting (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: (a) Pre-operative Sagittal computed tomography (CT) image demonstrating a type II Odontoid fracture. (b) 6-month post-operative sagittal CT scan image demonstrating fixation with anterior odontoid screw.

Similarly, in stable thoracolumbar fractures such as AO type A2 and A3, requiring spinal instrumentation, patients can undergo an implant removal following fracture healing. In these conditions, fracture healing with short-term fixation is the aim and not spinal fusion [1,2].

Stability in spine surgery is the capacity of the spinal column to withstand physiological loads without progressive deformity or neurological compromise. Spinal stabilization denotes the process of restoring this stability in a primarily unstable spine to prevent abnormal motion, protect neural structures, and maintain alignment [3].

It can be achieved through rigid instrumentation (pedicle screws, rods, hooks, Hartshill rectangle, sublaminar wires, interbody devices), dynamic or semi-rigid systems [4,5].

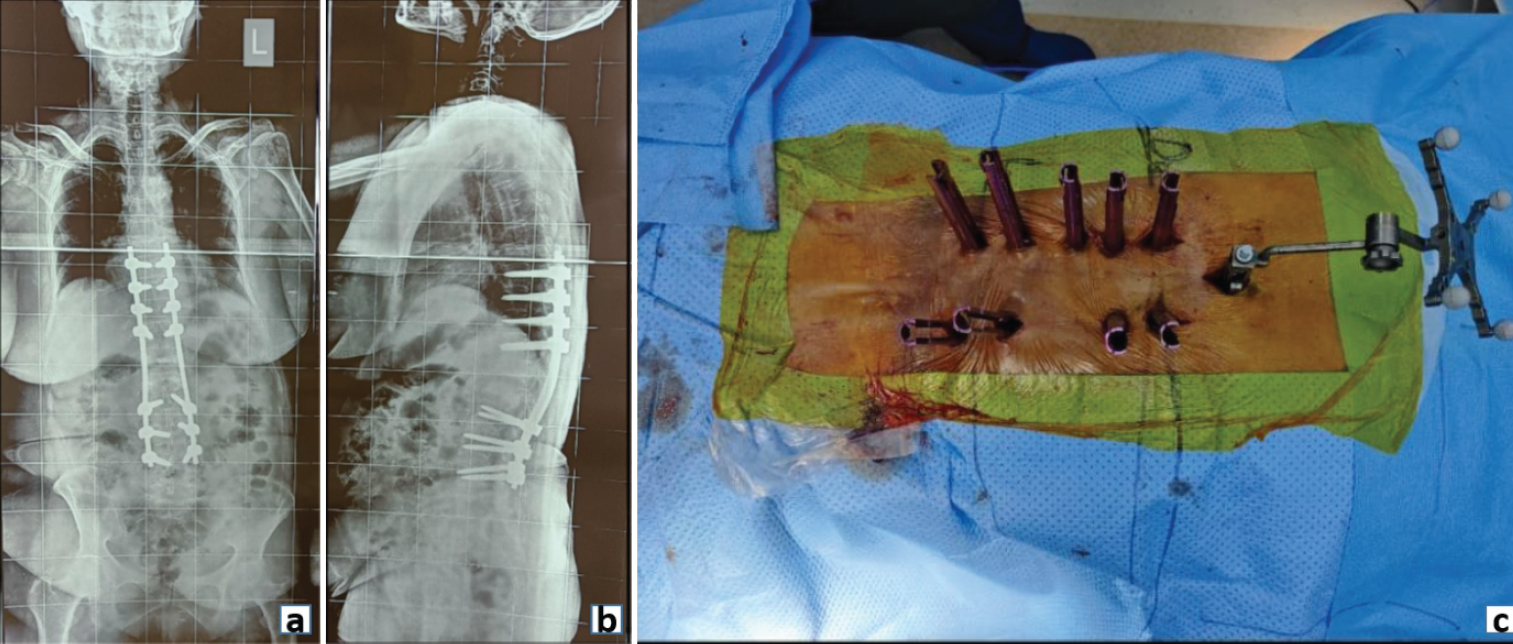

For instance, patients stabilized with terminal spinal metastatic disease may have a limited life span to achieve bony fusion. Moreover, their bone healing capacity is often compromised due to continuous chemoradiotherapy and poor nutritional status. For these reasons, the goals of spinal stabilization (with or without cement augmentation) in oncology patients include preservation of neurology, pain relief, arrest of progression of spinal deformity with an improved quality of life and overall survival (Fig. 4). Fusion may not be an essential prerequisite to achieve these goals. However, spinal stabilization with internal bracing is effective [6].

Figure 4: (a) Preoperative sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) film demonstrating an expansile lytic lesion of multiple myeloma at L4 vertebral level (sacralised L5). (b) Preoperative axial MRI image showing the extent of vertebral body involvement and the posterior elements at L4 level. (c) Post-operative anterior and (d) lateral radiograph demonstrating lumbopelvic stabilization of the spinal column in a case of multiple myeloma.

Figure 4: (a) Preoperative sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) film demonstrating an expansile lytic lesion of multiple myeloma at L4 vertebral level (sacralised L5). (b) Preoperative axial MRI image showing the extent of vertebral body involvement and the posterior elements at L4 level. (c) Post-operative anterior and (d) lateral radiograph demonstrating lumbopelvic stabilization of the spinal column in a case of multiple myeloma.

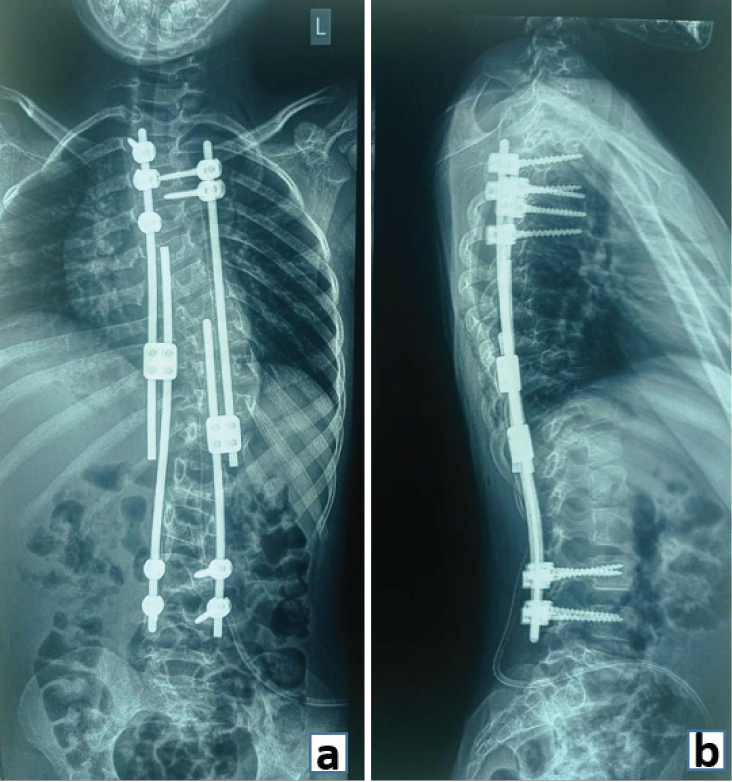

Similarly, growth rod constructs used in the treatment of early onset scoliosis are another illustration of spinal stabilization (Fig. 5). Growth rods provide a means to prolong final fusion and achieve control over the progression of deformity. Periodic distraction of growth rods is done to ensure adequate growth of the spinal column and correction of the deformity. This follows a final fusion procedure once spinal growth is complete [7].

Figure 5: (a) Anteroposterior and (b) Lateral radiograph demonstrating stabilization with pedicle screws and growth rods in a case of early onset scoliosis.

Figure 5: (a) Anteroposterior and (b) Lateral radiograph demonstrating stabilization with pedicle screws and growth rods in a case of early onset scoliosis.

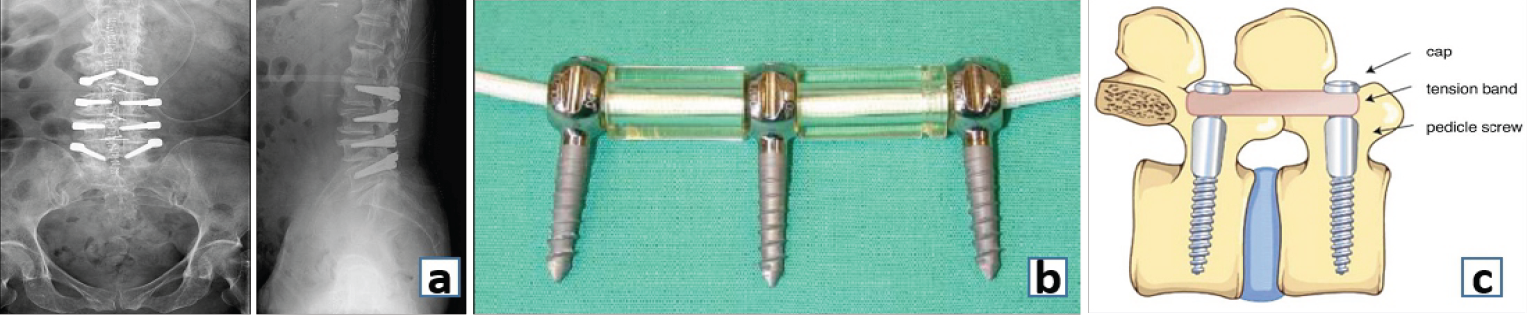

Dynamic stabilization aims to restore spinal stability while preserving motion at the affected segment. Introduced as an alternative to rigid fusion, it employs non-rigid constructs designed to control pathological motion and maintain alignment [8]. It allows some movement at the instrumented spinal segments while maintaining stability to prevent excessive movement. It was primarily intended for back pain and neck pain due to degenerative disease. Motion-preserving devices are classified as “prosthetic devices” and “dynamic stabilization devices.” Prosthetic devices replace the native disc in the spinal motion segment. Total disc replacement is an example of prosthetic devices. Dynamic stabilization devices work in conjunction with a motion segment without replacing any anatomical part of it [9]. The goals of dynamic stabilization devices are not only to preserve motion but also to prevent abnormal motion and unload the spinal motion segment by load sharing. Fatigue failure is the biggest obstacle for these devices in widespread adoption. Some forms of dynamic stabilization are interspinous spacers and pedicle screw-based instrumentation systems.

Graf ligamentoplasty

It involved the placement of pedicle screws, followed by connecting them with polyester bands instead of rods. Concerns with this device include overtightening of the polyester bands, leading to radicular symptoms (Fig. 6) [8].

Figure 6: (a) Anteroposterior and (b) Lateral radiograph showing the Dynesys system of dynamic stabilization. (c) Graphical representation of the Dynesys System. (d) Graf ligamentoplasty.

Figure 6: (a) Anteroposterior and (b) Lateral radiograph showing the Dynesys system of dynamic stabilization. (c) Graphical representation of the Dynesys System. (d) Graf ligamentoplasty.

Denesys

Denesys system was developed, which included a spacer between the polyester bands. However, it was not approved by the USFDA as a standalone device for non-fusion stabilization (Fig. 6) [10]. Other examples of dynamic stabilization are – Transition, Bioflex, Stabilimax, device for intervertebral assisted motion, and hybrid devices.

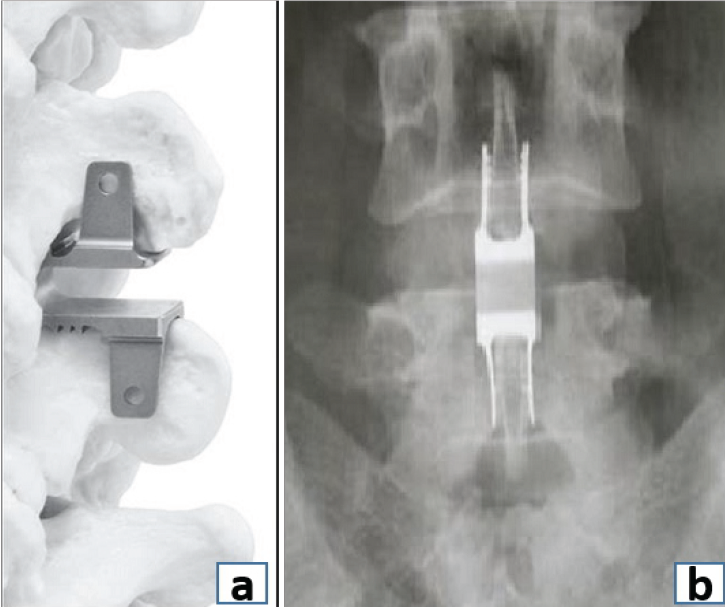

These are floating devices that do not require a bony anchorage like pedicle screws (Fig. 7). The common factor of all these devices is restriction of “some motion” and some degree of load sharing by the device with the motion segment [11]. They are useful in jacking up the foraminal space, leading to relief of foraminal nerve impingement.

Figure 7: (a) Placement of interspinous spacer device. (b) Anteroposterior radiograph showing the interspinous spacer device.

Figure 7: (a) Placement of interspinous spacer device. (b) Anteroposterior radiograph showing the interspinous spacer device.

Prosthetic devices

Degenerative disc disease has been mainly treated with fusion for the past century; however, concerns regarding the non-physiological nature of the procedure and alteration of stresses on the adjacent segments continue to persist. A total disc prosthesis aims to treat degenerative disc disease while maintaining motion and reducing the incidence of fusion-related comorbidities. It replaces the entire disc, annulus, and the endplates.

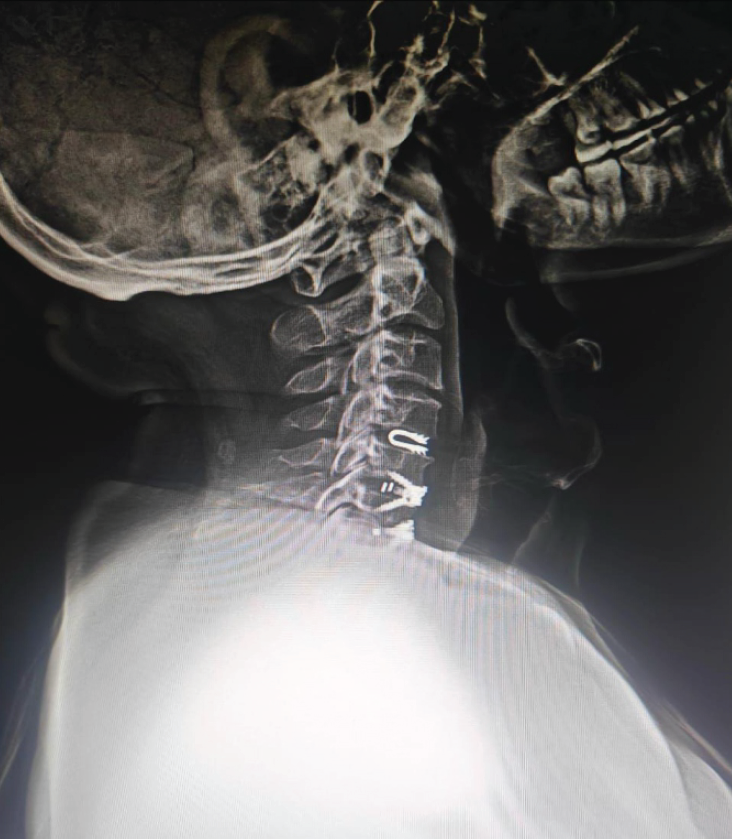

Cervical disc replacement

It has gained traction in the past few years as an alternative to anterior cervical discectomy and fusion in cervical degenerative disc disease. It preserves motion at the operative level, potentially reducing the risk of adjacent segment disease. However, concerns regarding heterotopic ossification, subsidence, and osteolysis remain (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Lateral cervical spine radiograph demonstrating a dynamic cervical implant at C4-5 level (blue arrow) above the two level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion done at C5-6 and C6-7 levels.

Figure 8: Lateral cervical spine radiograph demonstrating a dynamic cervical implant at C4-5 level (blue arrow) above the two level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion done at C5-6 and C6-7 levels.

Dynamic cervical implant

It is a U-shaped titanium one-piece non-fusion device – a novel treatment approach to cervical degenerative disc disease. It is designed to work as a shock-absorbing device that protects adjacent segments (Fig. 8).

Fusion is defined as bony continuity between two or more vertebral bodies. Fusion involves preparation of the bony surfaces at the site of intended fusion. Depending on the anatomical location, it can either be interbody fusion, which involves preparation of vertebral endplates and fusion between the two vertebral bodies, or posterolateral fusion, which involves decortication and fusion along the transverse processes.

Depending on instrumentation, it can either be instrumented or un-instrumented fusion.

Un-instrumented fusion

In modern spine surgery, it does not hold much significance. With advancements in the knowledge of spinal biomechanics and spinal fusion, the world has moved away from uninstrumented fusion.

Some of the early treatment options explored with un-instrumented fusion in high-grade spondylolisthesis include Capener, who described the treatment of patients with a bony dowel between L5 and S1 vertebrae. Similarly, in 1944, Milligan and Briggs described a posterolateral approach in which a bone peg was placed in the intervertebral disc space to augment a developing fusion mass in what can be described as a precursor to modern [12].

Instrumented fusion

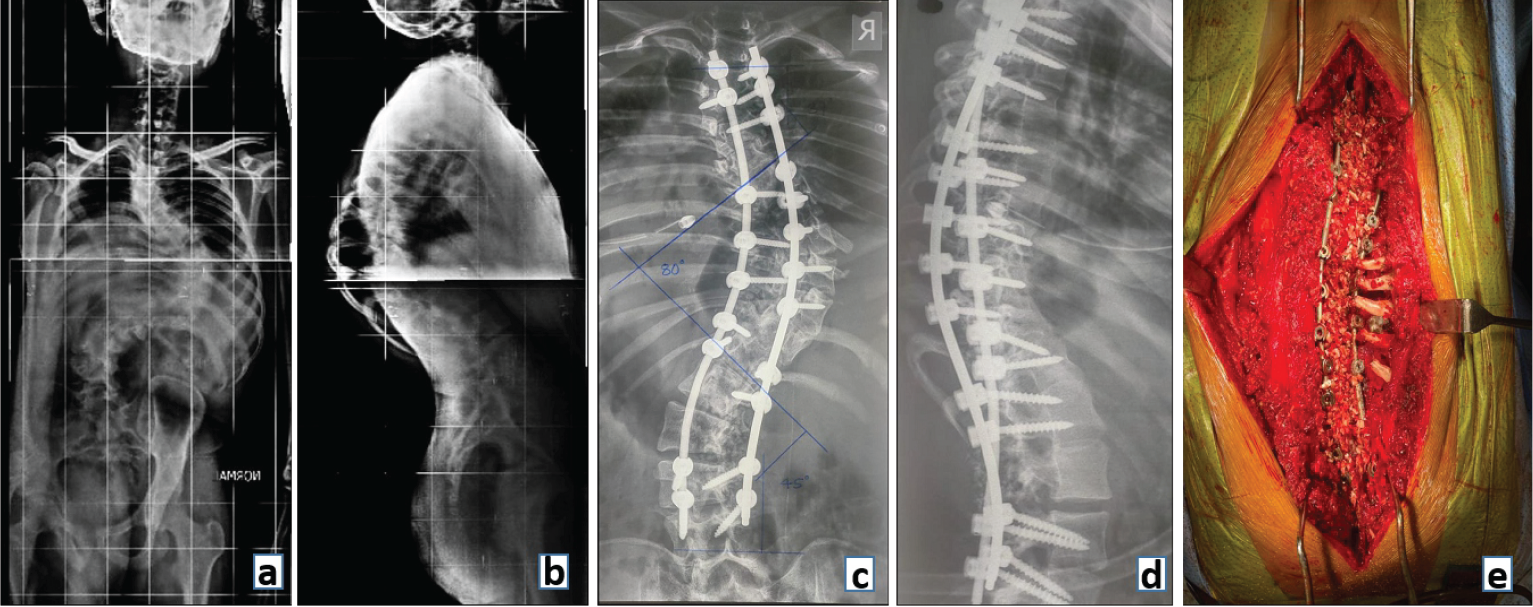

In the spine surgery of today, instrumented fusion involves fusion supported by pedicle screws and rods. The instrumentation provides short-term stability (months) to the spine until long-term stability is achieved by bony fusion of the spinal segments. It is an ongoing race between implant failure and bony fusion as to which comes first! (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Preoperative radiograph (a) anteroposterior and (b) lateral view showing a Double Major Curve Lenke type 3 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Postoperative (c) Anteroposterior and (d) Lateral radiograph showing deformity correction with fusion and posterior stabilization with (e) clinical image demonstrating bone graft laid across the fusion bed prepared by decorticating laminae and removing spinous processes.

Figure 9: Preoperative radiograph (a) anteroposterior and (b) lateral view showing a Double Major Curve Lenke type 3 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis. Postoperative (c) Anteroposterior and (d) Lateral radiograph showing deformity correction with fusion and posterior stabilization with (e) clinical image demonstrating bone graft laid across the fusion bed prepared by decorticating laminae and removing spinous processes.

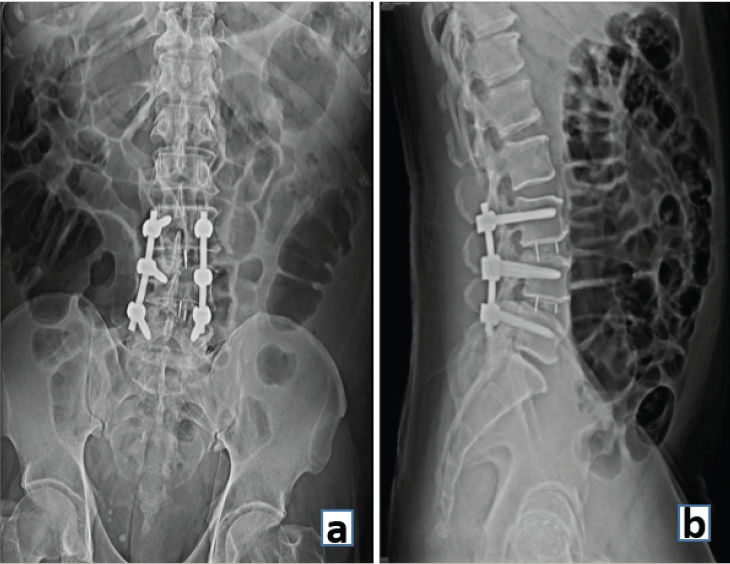

Interbody fusion uses a structural graft such as an allograft, autograft, or a metallic cage in the intervertebral disc space to stabilize an unstable spinal motion segment and promote fusion. FDA-approved intervertebral fusion cages in 1996, which led to a rapid growth in fusion rates for all spinal fusion procedures [13] (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: (a) Anteroposterior and (b) Lateral radiograph demonstrating interbody fusion at L3-4 and L4-5 levels and stabilization with posterior pedicle screws and rods.

Figure 10: (a) Anteroposterior and (b) Lateral radiograph demonstrating interbody fusion at L3-4 and L4-5 levels and stabilization with posterior pedicle screws and rods.

Currently, there are numerous approaches to achieve lumbar interbody fusion. All the approaches described below are essentially different ways to skin the cat! They all lead to interbody fusion as their outcome measure. We shall have a brief overview of the different approaches to interbody fusion in the lumbar spine.

Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF)

The anterior approach allows an anterior discectomy without entering the spinal canal or neural foramina. The ALIF procedure spares the posterior musculature and posterior ligamentous structures which are critical for spinal stability. However, this technique is known for visceral and vascular injuries.

Lateral lumbar interbody fusion (LLIF)

A lateral retroperitoneal approach with access possible from D12-L1 to L4-5 level. At the more caudal levels in the lumbar spine, the risk of injury to iliac vessels and the lumbar plexus is high. Advantages include less muscle injury with a thereby potential for faster post-operative mobilization.

Oblique lumbar interbody fusion (OLIF)

An alternative to LLIF reducing the risk of injury to lumbar plexus and psoas muscle as the approach to the disc space is anterior to psoas muscle. However, risks of sympathetic dysfunction and vascular injury remain.

Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF)

PLIF approach is a central posterior midline approach requiring significant dural retraction to access the disc space. Disadvantages of the PLIF technique include risk of injury to neural structures due to retraction and the delayed post-operative recovery due to extensive muscle and soft-tissue dissection.

Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF)

TLIF is a posterior unilateral approach to the disc space through the intervertebral foraminal space. It requires facetectomy to approach the disc space. Correction of coronal imbalance and lordosis restoration is limited with this approach.

Oblique LLIF/Transkambin lumbar interbody fusion

An oblique lateral lumbar approach with instrumentation passing through the kambins triangle. It does not require facet removal to access the disc space.

Endoscopic lumbar interbody fusion

Three commonly used trajectories to achieve interbody fusion are full endoscopic transkambin TLIF, biportal endoscopic TLIF and Endoscopic OLIF. Its growing popularity is attributed to reduction in peri- and post-operative morbiditiy, improved safety profile and favorable outcomes, including comparable post-operative complication and fusion rates to other MIS techniques. There is still no conclusive evidence regarding the superiority of any one particular approach over another. The lack of worldwide or even national guidelines and evidence for the treatment of different surgical indications has led to wide variability in surgical management.

Posterolateral fusion involves placement of bone graft in between the transverse processes of adjacent vertebrae after decortication of the posterior spinal elements. Local bone graft from decompression or iliac crest autograft is commonly used.

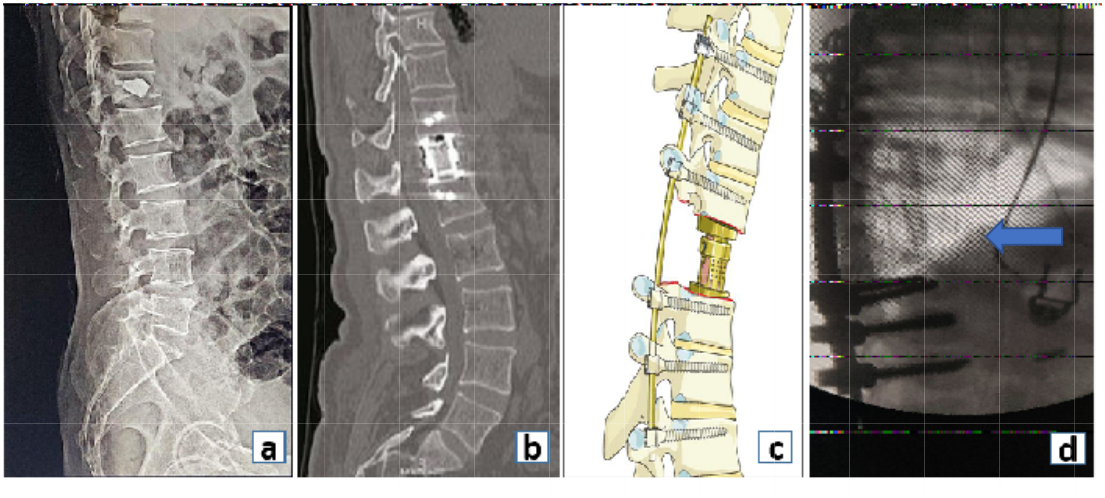

According to the Dennis column theory, spine is divided into three columns namely anterior, middle and posterior. Reconstruction refers to the construction of the damaged/deficient columns of the spine. Discussion begins with the fact that spine is a two column structure with anterior and middle column of the three column theory collapsed together into one column.

In a healthy spine, 80% of the load is carried by the anterior column while the remaining 20% is carried by the posterior column. Hence reconstruction of the anterior column in a defect assumes significance (Fig. 11).

Figure 11: Reconstruction of the anterior column with (a) bone cement, (b) cylindrical expandable cage, (c) pictorial image demonstrating expandable cage used for anterior column reconstruction, (d) and use of fibular strut graft (blue arrow) for anterior column reconstruction.

Figure 11: Reconstruction of the anterior column with (a) bone cement, (b) cylindrical expandable cage, (c) pictorial image demonstrating expandable cage used for anterior column reconstruction, (d) and use of fibular strut graft (blue arrow) for anterior column reconstruction.

The destruction of a particular spinal column can be multifactorial. It can be due to malignancy, traumatic spinal fractures, spinal infections and osteoporotic fractures to name a few.

Comminuted unstable thoracolumbar body fractures, with severe comminution of anterior column can overburden the posterior instrumentation and lead to failure. Corpectomy defects due to these fractures or tumors require an anterior reconstruction procedure. This can be achieved with strut grafts, femoral allografts, cylindrical cages, expandable cages or bone cement. The requirement of an anterior reconstruction procedure in severely comminuted thoracolumbar fractures has been well documented and quantified by the McCormack Load Sharing Classification [14].

Minimally invasive augmentation techniques such as kyphoplasty and vertebral body stenting can also be used to reconstruct the anterior column and restore the vertebral height.

The Bohlman technique used a fibular strut graft between L5 and the sacrum in high grade spondylolisthesis to stabilize and reconstruct the anterior column. Various modifications of the Bohlman technique continue to be used with high success and low rates of L5 radiculopathy [15].

The correct use of terminologies universally will lead to less discrepancies in communication and more standardization of these above concerned general terms.

The appropriate understanding and usage of each term will help the surgeons and the staff working within the surgeons’ team to formulate informed and better post-operative plans leading to ultimately to better post-operative patient outcomes.

The strict adherence to appropriate use of terminologies prevents misinterpretation of literature. It leads to seamless collaboration of knowledge and ideas in the scientific community.

References

- 1. Diniz JM, Botelho RV. Is fusion necessary for thoracolumbar burst fracture treated with spinal fixation? A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Spine 2017;27:584-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kocanli O, Komur B, Duymuş TM, Guclu B, Yılmaz B, Sesli E. Ten-year follow-up results of posterior instrumentation without fusion for traumatic thoracic and lumbar spine fractures. J Orthop 2016;13:301-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kim CW, Perry A, Garfin SR. Spinal instability: The orthopedic approach. Semin Musculoskelet Radiol 2005;9:77-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Izzo R, Guarnieri G, Guglielmi G, Muto M. Biomechanics of the spine. Part I: Spinal stability. Eur J Radiol 2013;82:118-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Davis W, Allouni AK, Mankad K, Prezzi D, Elias T, Rankine J, et al. Modern spinal instrumentation. Part 1: Normal spinal implants. Clin Radiol 2013;68:64-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Drakhshandeh D, Miller JA, Fabiano AJ. Instrumented spinal stabilization without fusion for spinal metastatic disease. World Neurosurg 2018;111:e403-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Yazici M, Olgun ZD. Growing rod concepts: State of the art. Eur Spine J 2013;22 Suppl 2:S118-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Kanayama M, Hashimoto T, Shigenobu K. Rationale, biomechanics, and surgical indications for graf ligamentoplasty. Orthop Clin North Am 2005;36:373-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Serhan H, Mhatre D, Defossez H, Bono CM. Motion-preserving technologies for degenerative lumbar spine: The past, present, and future horizons. SAS J 2011;5:75-89. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. St-Pierre GH, Jack A, Siddiqui MM, Henderson RL, Nataraj A. Nonfusion does not prevent adjacent segment disease: Dynesys long-term outcomes with minimum five-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:265-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Bono CM, Vaccaro AR. Interspinous process devices in the lumbar spine. J Spinal Disord Tech 2007;20:255-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Lorenz R. Lumbar spondylolisthesis. Clinical syndrome and operative experience with Cloward’s technique. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 1982;60:223-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Jain S, Eltorai AE, Ruttiman R, Daniels AH. Advances in spinal interbody cages. Orthop Surg 2016;8:278-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Filgueira ÉG, Imoto AM, Da Silva HE, Meves R. Thoracolumbar burst fracture: McCormack load-sharing classification: Systematic review and single-arm meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2021;46:E542-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Hart RA, Domes CM, Goodwin B, D’Amato CR, Yoo JU, Turker RJ, et al. High-grade spondylolisthesis treated using a modified Bohlman technique: Results among multiple surgeons. J Neurosurg Spine 2014;20:523-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]