Hip arthroscopy and chondrofiller application is an effective, minimally invasive, single stage procedure for treating osteochondral defects of femoral head.

Dr. Srinivas Thati, Department of Orthopaedics, AIG Hospitals, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: drthati@hotmail.com

Introduction: Osteochondral lesions of the femoral head are rare and often underdiagnosed due to subtle imaging findings. Early identification and appropriate management are crucial to avoid long-term joint degeneration, particularly in young, active individuals.

Case Report: We present the case of a 32-year-old male who developed persistent right hip pain following a fall. Imaging with computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed a focal osteochondral defect of the femoral head with a displaced fragment. Hip arthroscopy identified a 15 mm × 5 mm chondral lesion over the superoanterior weight-bearing dome. The defect was debrided and filled with Chondrofiller, a cell-free, collagen-based scaffold, without performing microfracture. Post-operatively, the patient demonstrated complete pain relief, full hip range of motion, and a normal gait.

Conclusion: Arthroscopic application of Chondrofiller is a promising, minimally invasive option for treating focal chondral defects of the femoral head. It preserves the subchondral bone and eliminates the need for more invasive or staged procedures. This case highlights its potential for early joint preservation, though long-term studies are warranted.

Keywords: Osteochondral defect, femoral head, hip arthroscopy, chondrofiller, cartilage repair, arthroscopy.

The femoral head cartilage plays a crucial role in the frictionless movements of the hip joint. It distributes load, absorbs shock, and transfers forces across the joint [1,2]. The thickness of femoral head articular cartilage is about 2–4 mm. The structure of femoral head cartilage is complex. McCall described three zones in the fibrous structure–a superficial layer of large parallel fibers, an intermediate zone of unoriented fibers, and a radial zone of tightly packed fibers [3]. Each zone has its function. The superficial zone resists the tensile, shear, and compressive forces because of its tightly packed collagen fibers. Whereas the intermediate zone provides a functional and anatomical bridge between the other two layers and acts as the first line of resistance to compressive forces. The deeper zone provides resistance to compressive forces [4]. The incidence of hip osteochondral injuries is less than that of ankle and knee osteochondral injuries. These are particularly seen in active individuals, such as athletes [5]. Their incidence has been on the rise recently because of the wider usage of advanced imaging, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and hip arthroscopy, particularly for femoral impingement (FAI) [6]. However, the true incidence is difficult to estimate because of the underdiagnosis. Trauma during sports or motor vehicle collision is the key causative factor, followed by repetitive microtrauma as seen in FAI [7]. Osteochondral lesions of the femoral head can result in persistent pain, restricted mobility, altered biomechanics at the hip, and thus significantly affect the patient’s quality of life, productivity, and dependence on analgesics [8]. It is essential to diagnose early and treat effectively to prevent early arthritis of the hip joint. Hip arthroscopy is both diagnostic and therapeutic for osteochondral lesions of the hip when combined with other procedures. We are presenting a case of a young male with a traumatic osteochondral lesion of the hip treated with hip arthroscopy and Chondrofiller application.

A 32-years-old male patient presented after a fall from height in January 2024, and sustained a flank injury and a left distal radius comminuted fracture. He had diffuse pain at the groin and hip; however, subsequently, after a month, pain localized to the right hip, which gradually worsened, limiting his walking distance not more than a few hundred yards. He has no fever episodes or systemic constitutional symptoms. On clinical examination, he had an antalgic gait and a positive Trendelenburg test on the right side. There was no localized tenderness over the hip joint. The range of movements of the hip was preserved, but with pain during deep rotations. The right leg appeared relatively longer (apparent length). No signs of femoro-acetabular impingement. Harris Hip Score was 36, reflecting severe functional limitation.

Investigations

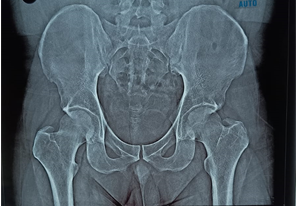

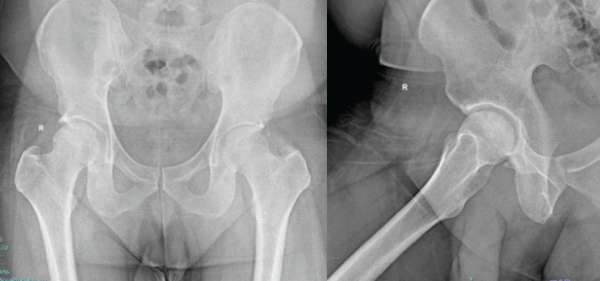

Initial assessment with plain radiographs did not reveal any obvious abnormality (Fig. 1). Hence, advanced imaging with computed tomography (CT) and MRI were performed.

Figure 1: Plain radiograph of the pelvis.

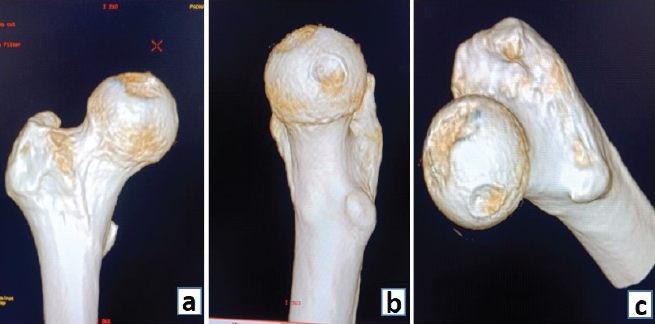

CT scan revealed a large osteochondral defect in the weight-bearing area of the femoral head, with the fragment displaced into the inferior joint space (Fig. 2a, b, c).

Figure 2: (a-c) 3D computed tomography images showing the defect.

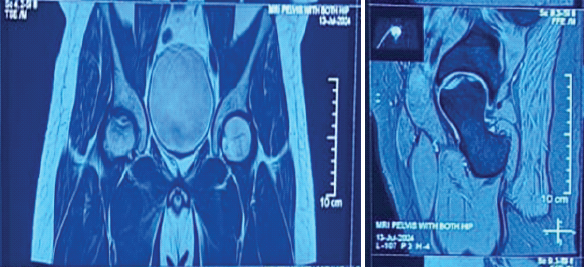

MRI scan of the right hip demonstrated an osteochondral defect of the femoral head with associated subchondral edema (Fig. 3a and b). There were no obvious signs of avascular necrosis (AVN) of the femoral head.

Figure 3: (a and b) Magnetic resonance images showing altered signal intensity in the anterosuperior aspect of the right femoral head.

Routine blood workup was unremarkable. Given the symptoms and mechanical joint compromise, surgical intervention was planned.

Procedure

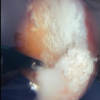

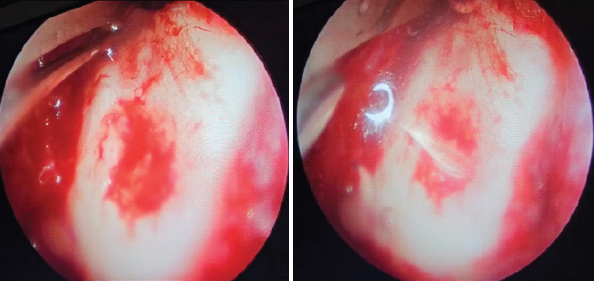

The procedure was performed under spinal anesthesia, in a supine position. Hip traction was applied. Antibiotic (Injection Cefuroxime 1.5 g) administered before skin incision. An anterolateral portal was established under C-arm guidance. Modified anterior portal established under direct vision. Diagnostic hip arthroscopy was performed, revealing a focal osteochondral defect of size 15 mm × 5 mm located over the weight-bearing superoanterior dome of the femoral head (Fig. 4). The acetabulum and labrum were normal.

Figure 4: Arthroscopic image showing the chondral defect.

The hip capsule was debrided for better exposure. The osteochondral defect was debrided with a curette and rasped to achieve a stable margin. Saline suction was done. CO2 insufflation was applied at 8 mmHg to facilitate drying of the defect. Chondrofiller was then carefully injected into the defect (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: (a) Before applying Chondrofiller, (b) after Chondrofiller application.

The portals are closed with Ethilon sutures and a sterile dressing was applied.

Rehabilitation program included touch weight bearing on the right lower limb for 6 weeks along with leg elevation and active movements of the hip. Hip abductor strengthening, static and dynamic quadricep strengthening exercises. Post-operatively, at 6 weeks, the patient had a good range of movements of the hip, was able to fully weight bear and walk independently without assistance. At 3 months post-operatively, the patient reported significant improvement in pain and function. He was walking independently with a normal gait, the Trendelenburg test was negative, and hip range of motion was full and painless (110° of hip flexion and normal rotations). The Harris hip score improved from 36 pre-operatively to 89 at follow-up. Follow-up radiograph at 1 year showed good joint space, congruent articular surfaces, and no evidence of AVN of the femoral head (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the right hip at 1-year follow-up.

Osteochondral defects of the femoral head are rare compared to the knee and ankle joints. The exact prevalence is unknown [9]. These are also commonly missed in the radiographs. These can result from trauma, subchondral insufficiency fractures, AVN, or osteochondritis dissecans (OCD). MRI is a key in differentiating these conditions by identifying features, such as marrow edema, fracture lines, the double-line sign of AVN, cam or pincer, or a well-demarcated lesion in OCD. In young patients without systemic risk factors, post-traumatic focal lesions are more likely to be isolated OCDs than early AVN [10]. As the articular cartilage has less healing capacity, non-operative or conservative treatment options (rest, physical therapy, and anti-inflammatory drugs) are limited and may be unsuccessful. Delayed or missed presentation will put the articular cartilage at risk of irreversible damage, subchondral bone collapse, limiting the effectiveness of joint preserving procedures [11]. Popular treatment options include debridement (chondroplasty), microfractures, autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI), osteochondral autograft transfer, and total hip replacement in severe cases. Less commonly used procedures are mesenchymal stem cell injections, bone marrow aspirate concentrate, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections, hyaluronic acid (HA) injections, and prosthetic biocomposites.

HA

HA injections do not provide a cure for hip chondral lesions, but they can offer substantial relief from symptoms by lubricating the joint and also stimulate the proliferation of chondrocytes, which are essential in cartilage formation [12].

PRP

The regenerative role of PRP in cartilage repair is still controversial. In animal studies, it has shown chondrocyte regeneration; however, its use in human joints is debatable. Battaglia et al., compared PRP and HA injections and found that both are equally effective and none is found to be superior to the other [13]. One benefit of PRP is that it is autologous in nature, thus has a good safety profile and low side effects [14]. Additional studies are warranted for a better understanding of its therapeutic potential. Surgical options always remain the mainstay of treatment in managing osteochondral defects of the hip.

Chondroplasty

It is the most commonly performed procedure along with hip arthroscopy, accounting for 50% [15]. It is used in low-grade, partial thickness cartilage defects only and is not useful in arthritic joint. It involves smoothening or rasping the unstable chondral tears, preventing loose body formation, and removing the mechanical blocks [16]. However, the decision to perform chondroplasty has to be individualized based on each case.

Microfractures

This technique involves creating multiple small perforations in the subchondral bone. This penetrates the marrow space and stimulates bleeding. The influx of mesenchymal stem cells and growth factors from the marrow promotes the formation of reparative fibrocartilage by stimulating chondrocytes [17]. The success of microfracture depends on various factors, such as the size and location of the lesion, the patient’s age, and level of physical activity. The fibrocartilage that is formed is not as strong as the hyaline cartilage, raising concerns about its strength and durability [18]. The use of implantable scaffolds can help maintain the fibrin clot within the defect, bone morphogenetic proteins have also been tried [19,20]. Philippon et al., in their study on 9 patients, showed good results with microfractures in 8 of them [21].

ACI

Chondral injuries that are too large for microfractures can be treated with ACI. It is a two-stage procedure, in which healthy chondrocytes are harvested and cultured in the lab in the first stage, and implantation of cultured cells and matrix into the defect in the second stage [22]. Akimau et al. [23] reported a case of femoral head osteonecrosis in a 31-year-old male treated with ACI, demonstrating significant improvement in Harris hip score and overall functional outcomes. Similarly, Fontana et al. [24] in a retrospective comparative study demonstrated that patients treated with ACI had significantly better Harris Hip Scores compared to those who underwent debridement, with sustained improvements observed over a mean follow-up period of 5 years.

Osteochondral autograft transplantation

This method involves the transplantation of osteochondral plugs that are harvested from non-weight-bearing surfaces to fill larger chondral defects. This is similar to mosaicplasty, where multiple osteochondral plugs are used to fill multiple smaller defects [25]. However, this is a technically demanding procedure and being a newly developed procedure, there is limited long-term data available [26,27].

Chondrofiller

Chondrofiller is a cell-free collagen-based product, rich in type 1 collagen that promotes cartilage regeneration by supporting the migration and differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells, particularly the chondrocytes [28]. It is derived from rat tail tendons. The liquid components of the product are supplied in a two-chamber syringe. By placing a mixing adapter on the syringe and pressing out the components, they are mixed, and the pH-dependent gelation of the collagen starts immediately once the collagen has been implanted in the cartilage defect. The quicker they are pressed through the mixing adapter of the two-chamber syringe, the more stably the implant matrix solidifies. In the process, the cartilage defect is filled completely with the collagen matrix, with a minimal amount above the surrounding cartilage. Hardening of the matrix takes 2–5 min under an optimum processing temperature of 30–33°C. This process is visible, as the initially clear gel changes to a milky, opaque appearance. The usage of Chondrofiller is on the rise recently because of the promising results it has been showing. The advantage over other cartilage treatment procedures, for example, microfracture surgery, together with osteochondral transplant surgery or autologous chondrocyte transplantation, because it is used without the need to perform microfractures, which might prove difficult to perform in the hip joint, and without the need of a lengthy time cell culture [29]. Of late, Chondrofiller has also been used in the glenoid chondral defects. Recent studies have advocated the use of Chondrofiller Liquid in the knee and tibiotalar joint, demonstrating excellent clinical outcomes [30,31,32]. However, only limited case reports have described its application in the hip.

Mazek et al., has excellent results at 12–60 months follow-up, in their prospective study conducted on 26 patients with femoral head and acetabular chondral defects, treated with Chondrofiller [28]. In a prospective study on 64 patients with osteochondral defects of the knee by Jerosch et al., there were very good mid-term results at 4 years in the functional scores (IKDC, SF 36) [33]. Corain et al., conducted a study on the infiltration of Chondrofiller liquid in trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. A single infiltration of ChondroFiller under fluoroscopic guidance was performed, followed by a clinical re-evaluation 30 days after infiltration with the administration of the DASH score and NRS. The results of the study show that there was an improvement in pain symptoms, associated with an increase in force in the pincer and grip movements evaluated with clinical tests [34]. Although MRI at 6 months showed little change in bone edema and joint effusion, the marked clinical improvement suggests that imaging findings may not fully correlate with early symptomatic relief, raising the question of optimal timing for MRI evaluation. This study allowed to confirm the potential use of ChondroFiller Liquid also in the field of small joints. The decision to use Chondrofiller in this case was driven by several factors, such as focal nature of the lesion, young age, joint-preserving approach, and minimally invasive approach. Microfractures are also widely practiced; pose technical challenges in terms of the constrained environment of the hip joint, and it can violate the integrity of the subchondral bone sometimes. By obviating the need for microfractures, Chondrofiller preserves the subchondral architecture. Chondrofiller also provides a one-stage solution for chondral defects, in contrast to ACI, which is two-staged. However, Chondrofiller does have its own limitations. The optimum size of the defect should be <2.5 cm2. Being a relatively newly developed technique, long-term outcomes are lacking. It is also ineffective in large, cystic lesions and with a poor biological environment. Cost remains a significant limitation.

Early identification and appropriate intervention in focal osteochondral defects of the femoral head are crucial to prevent progressive joint degeneration and maintain hip function, particularly in young, active individuals. Arthroscopic application of Chondrofiller offers a promising, minimally invasive biological solution by supporting cartilage regeneration without the morbidity associated with cell harvesting or microfractures. Our case reinforces the advantage of Chondrofiller over other traditional approaches. Future studies with larger cohorts and longer follow-ups are needed to further validate these findings.

Focal osteochondral defects of the hip are often missed or underdiagnosed, but can lead to significant morbidity. This case illustrates that hip joint arthroscopy and Chondrofiller application, a minimally invasive cartilage regeneration technique, can effectively restore joint function and relieve pain in affected individuals.

References

- 1. Bullough PG, Goodfellow J. The significance of the fine structure of articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1968;50:852-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Sophia Fox AJ, Bedi A, Rodeo SA. The basic science of articular cartilage: Structure, composition, and function. Sports Health 2009;1:461-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Clarke IC. Surface characteristics of human articular cartilage–a scanning electron microscope study. J Anat 1971;108:23-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Akizuki S, Mow VC, Müller F, Pita JC, Howell DS, Manicourt DH. Tensile properties of human knee joint cartilage: I. Influence of ionic conditions, weight bearing, and fibrillation on the tensile modulus. J Orthop Res 1986;4:379-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Flanigan DC, Harris JD, Trinh TQ, Siston RA, Brophy RH. Prevalence of chondral defects in athletes’ knees: A systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:1795-801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Philippon MJ, Schenker ML, Briggs KK, Kuppersmith DA. Femoroacetabular impingement in 45 professional athletes: Associated pathologies and return to sport following arthroscopic decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2007;15:908-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Beck M, Kalhor M, Leunig M, Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: Femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2005;87:1012-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. McCarthy JC, Lee JA. Osteochondral injuries of the femoral head. Instr Course Lect 2000;49:321-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Edmonds EW, Heyworth BE. Osteochondritis dissecans of the shoulder and hip. Clin Sports Med 2014;33:285-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Kijowski R, De Smet AA, Mukharjee R, Stanton P, Fine JP. Osteochondral lesions of the knee: Differentiating the most common entities at MRI. Radiographics 2018;38:1478-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. El Bitar YF, Lindner D, Jackson TJ, Domb BG. Joint-preserving surgical options for management of chondral injuries of the hip. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2014;22:46-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Migliore A, Bizzi E, Herrero-Beaumont J, Petrella RJ, Raman R, Chevalier X. The discrepancy between recommendations and clinical practice for viscosupplementation in osteoarthritis: Mind the gap! Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2015;19:1124-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Battaglia M, Guaraldi F, Vannini F, Rossi G, Timoncini A, Buda R, et al. Efficacy of ultrasound-guided intra-articular injections of platelet-rich plasma versus hyaluronic acid for hip osteoarthritis. Orthopedics 2013;36:e1501-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Bennell KL, Hunter DJ, Paterson KL. Platelet-rich plasma for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2017;19:24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Yen YM, Kocher MS. Chondral lesions of the hip: Microfracture and chondroplasty. Sports Med Arthrosc Rev 2010;18:83-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Sampson TG. Arthroscopic treatment for chondral lesions of the hip. Clin Sports Med 2011;30:331-48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Chen H, Sun J, Hoemann CD, Lascau-Coman V, Ouyang W, McKee MD, et al. Drilling and microfracture lead to different bone structure and necrosis during bone-marrow stimulation for cartilage repair. J Orthop Res 2009;27:1432-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Erggelet C, Vavken P. Microfracture for the treatment of cartilage defects in the knee joint – a golden standard? J Clin Orthop Trauma 2016;7:145-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Hoemann CD, Hurtig M, Rossomacha E, Sun J, Chevrier A, Shive MS, Buschmann MD. Chitosan-glycerol phosphate/blood implants improve hyaline cartilage repair in ovine microfracture defects. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005;87:2671-86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Jelic M, Pecina M, Haspl M, Kos J, Taylor K, Maticic D, et al. Re-generation of articular cartilage chondral defects by osteogenic protein-1 (bone morphogenetic protein-7) in sheep. Growth Factors 2001;19:101-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Philippon MJ, Schenker ML, Briggs KK, Maxwell RB. Can microfracture produce repair tissue in acetabular chondral defects? Arthroscopy 2008;24:46-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Fortun CM, Streit J, Patel SH, Salata MJ. Cartilage defects in the hip. Oper Tech Sports Med 2012;20:287-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Akimau P, Bhosale A, Harrison PE, Roberts S, McCall IW, Richardson JB, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation with bone grafting for osteochondral defect due to posttraumatic osteonecrosis of the hip–a case report. Acta Orthop 2006;77:333-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Fontana A, Bistolfi A, Crova M, Rosso F, Massazza G. Arthroscopic treatment of hip chondral defects: Autologous chondrocyte transplantation versus simple debridement–a pilot study. Arthroscopy 2012;28:322-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Viamont-Guerra MR, Bonin N, May O, Le Viguel- loux A, Saffarini M, Laude F. Promising outcomes of hip mosaicplasty by minimally invasive anterior approach using osteochondral autografts from the ipsilateral femoral head. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020;28:767-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Bakircioglu S, Atilla B. Hip preserving procedures for osteonecrosis of the femoral head after collapse. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2021;23:101636. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Kocadal O, Akman B, Güven M, Şaylı U. Arthroscopic-assisted retrograde mosaicplasty for an osteochondral defect of the femoral head without performing surgical hip dislocation. SICOT J 2017;3:41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Mazek J, Gnatowski M, Salas AP, O’Donnell JM, Domżalski M, Radzimowski J. Arthroscopic utilization of ChondroFiller gel for the treatment of hip articular cartilage defects: A cohort study with 12- to 60-month follow-up. J Hip Preserv Surg 2021;8:22-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Hevesi M, Bernard C, Hartigan DE, Levy BA, Domb BG, Krych AJ. Is microfracture necessary? Acetabular chondrolabral debridement/abrasion demonstrates similar outcomes and survival to microfracture in hip arthroscopy: A multicenter analysis. Am J Sports Med 2019;47:1670-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Syed RF, Rachha R, Thati S. Chondrofiller and treatment of cartilage defects in the knee. Acta Sci Orthop 2024;7.10:3-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Syed RF, Thati S, Rachha R. Chondrofiller application for osteochondral lesions of the talus: Case series and surgical technique. J Foot Ankle Surg (Asia-Pacific) 2025;12:84-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Simeonov E. Implantation of ChondroFiller Liquid® as a scaffold material for the treatment of chondral lesions of the knee joint. J IMAB Annu Proc Sci Paper 2024;30:5936-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Jerosch J, Joseph P. Mittelfristige ergebnisse der regeneration artikulärer knorpeldefektemittels zellfreier kollagenmatrix (chondrofiller liquidTM). OUP 2020;9:109-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 34. Corain M, Zanotti F, Giardini M, Gasperotti L, Invernizzi E, Biasi V, et al. The use of an acellular collagen matrix chondrofiller® liquid for trapeziometacarpal osteoarthritis. J Arthritis 2023;12:1-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]