This article describes a common injury presenting in an uncommon age group and how the management protocol can change for these injuries, and where the dilemmas can arise.

Dr. Prasad Bhagunde, SportsOrtho, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: prasadbhagunde27@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteochondral lesions of the lateral femoral condyle (LFC) following patellar dislocation are relatively rare and typically observed in the adolescent population. In adults, such injuries–especially involving a large osteochondral fragment from the posterolateral aspect of the condyle–are exceedingly uncommon and pose both diagnostic and therapeutic challenges.

Case Report: We present the case of a 20-year-old male who sustained a traumatic right knee injury while playing basketball. Clinical examination and imaging revealed a large osteochondral fragment (2.5 × 2.5 cm) originating from the posterolateral aspect of the LFC, accompanied by a complete tear of the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL). Notably, the patient demonstrated generalized joint hypermobility (Beighton score 6/9) and patellar maltracking features, including patella alta and increased tibial tubercle–trochlear groove distance. The patient underwent combined arthroscopic and open surgical management. Diagnostic arthroscopy confirmed an intra-articular floating osteochondral fragment, which was removed, anatomically reduced, and fixed using bioabsorbable pins and headless compression screws through a lateral parapatellar arthrotomy. Concurrently, MPFL reconstruction was performed using a semitendinosus and gracilis autograft fixed with suture anchors and an endobutton system.

Conclusion: This case underscores the importance of high clinical suspicion for osteochondral injury in adult patellar dislocation, especially in patients with underlying joint hypermobility or anatomical predispositions.

Keywords: Medial patellofemoral ligament, knee dislocation, osteochondral fracture, sports injury.

Traumatic injuries to the knees are an increasing concern as the level of physical activities and sports players is increasing. Such injuries to the knee in adolescent age groups are not uncommon and generally lead to an osteochondral lesion or a chondral lesion. These chondral lesions are more prevalent in the pediatric age group (<12), whereas the osteochondral lesions are a little more common and are seen more in adolescent patients. It has been documented in literature that approximately one-third of all patellar dislocations show an osteochondral fragment as a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) finding [1]. These post-traumatic patellar dislocations are most commonly associated with osteochondral fragments from the medial patellar facet or the lateral femoral condyle (LFC) [2]. Based on the size of the osteochondral fragment, there are currently various treatment modalities that are being used, which can range from excision of the fragment to fixation of the fragment with bioabsorbable pins. Some fragments may not be amenable to fixation and could be so large that the defect on the femoral condyle can not be left alone. Many newer options, which allow cartilage of the condyle to heal, are now possible, such as Osteochondral Autograft Transfer System (OATS) and Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (ACI) [3]. We report a rare case of patellar instability with a large osteochondral fragment of the LFC in an adult. According to our current understanding, this is only the first such case reported in an adult.

A 20-year-old male (dimensions) presented to our emergency department following a direct injury to his right knee, which occurred while playing basketball. He complained of a click in his right knee joint while playing the sport, which was associated with a suspected lateral patella dislocation that spontaneously relocated. This was associated with severe pain and swelling of the right knee joint. The patient was unable to bear weight following the injury and was brought to our emergency department immediately afterwards. On examination in the emergency department, the patellar appeared relocated, and he had some amount of lateral laxity and apprehension, but it was difficult to assess the laxity due to the swelling of the right knee joint. The patient had tenderness on the lateral aspect of the knee along with inability to move the knee through the range of motion (ROM) more than 0–40° of ROM due to pain and swelling. He was comfortable at 20° of flexion of the knee joint. The patient reported no previous episode of patella dislocation, but did report some injury to the same knee 5 years ago; but he did not have any details of the incident. On examination for generalized laxity, his Beighton Score was 6/9, which corresponds to excessively hypermobile. Fig. 1

Figure 1: Radiographs on presentation of the patient to our emergency room – right knee anteroposterior and lateral view.

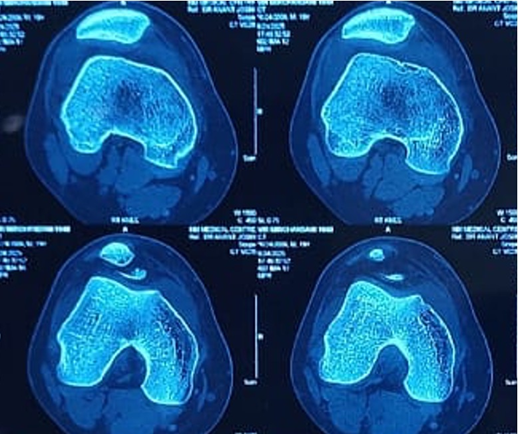

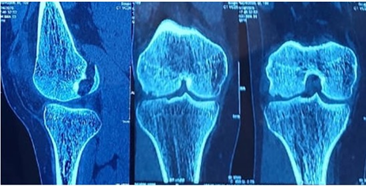

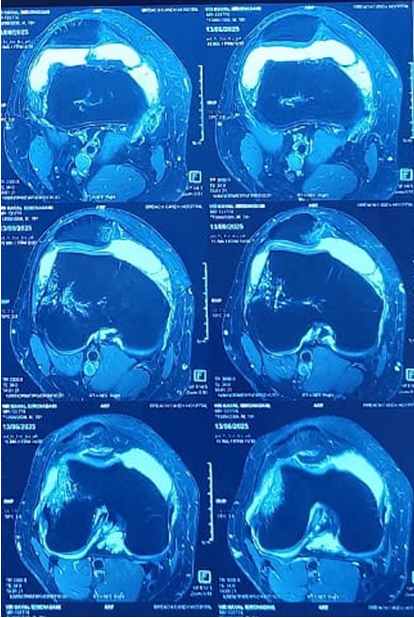

The patient was administered painkillers and ice fomentation and underwent an X-ray of his knee joint. An osteochondral fragment was visible in the knee joint, but we were not able to determine where the origin of the fragment was. A computed tomography scan of the knee joint was performed, and the fragment was identified to be originating from the distal LFC and was measuring 2.5 cm × 2.5 cm. The Insall Salvati ratio was 1.36, and the Caton Deschamps Ratio was 1.6. The Tibial Tuberosity–Trocheal Groove (TT–TG) distance was 20 mm, and his knee was a Dejour type B. A standing scannogram was not possible for the patient due to pain. The decision to avoid a tuberosity osteotomy was made as the TT-TG distance was just at the borderline with a slightly high Caton–Deschamps index. The decision to perform a lateral parapatellar arthrotomy with a strong medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) reconstruction was deemed sufficient to maintain patella stability. The final decision would be taken intraoperatively after tightening of the MPFL graft regarding the requirement of a tuberosity osteotomy. Fig. 2, 3.

Figure 2: Computed tomography scan of right knee – axial cuts.

Figure 3: Computed tomography scan of right knee – coronal and sagittal cuts.

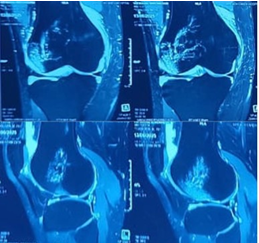

The patient was given a Long Knee immobilizer along with analgesics and was discharged home. He was advised to undergo an MRI of the right knee after 72 h once the swelling subsided. The MRI was done and along with the osteochondral defect and bony edema, the MRI showed a complete tear of the MPFL. Fig. 4,5

Figure 4: Magnetic resonance imaging of right knee – axial cuts.

Figure 5: Magnetic resonance imaging of right knee – coronal and sagittal cuts.

On examination, the patella showed greater lateral translation on the right side compared to the left side. The patella showed a positive patella glide (quadrant test) with a severe grade (>2 and <4) of lateral translation. The Sagittal Engagement Index was 0.51 (Normal).

The patient was planned for a surgery – an MPFL reconstruction and arthroscopic evaluation of the lateral femoral osteochondral fragment, and the patient was informed that once the evaluation of the fragment was done, an intraoperative decision would be made regarding the management of the fragment. The patient’s consent was taken for this plan, and this was conveyed to his family members.

After a complete anesthetic workup, the patient was administered general anesthesia for the procedure and was placed in the supine position with a side support on a radiolucent table for intraoperative fluoroscopic visibility.

On examination under anesthesia, the patient had a positive patella lateral translation on the right side with a severe grade patella glide. A tourniquet was used for the surgery.

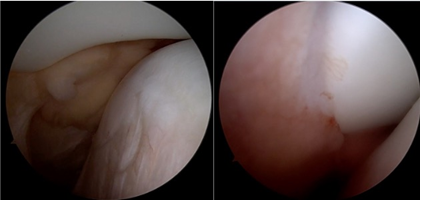

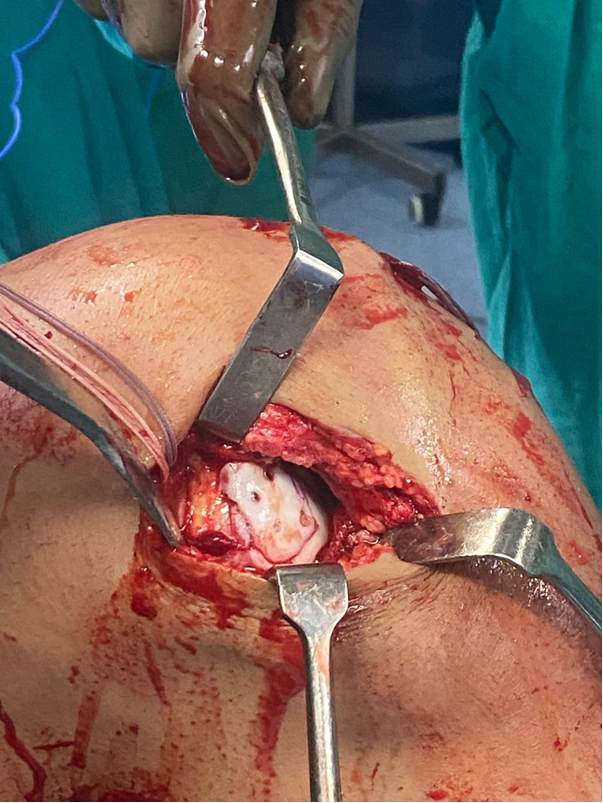

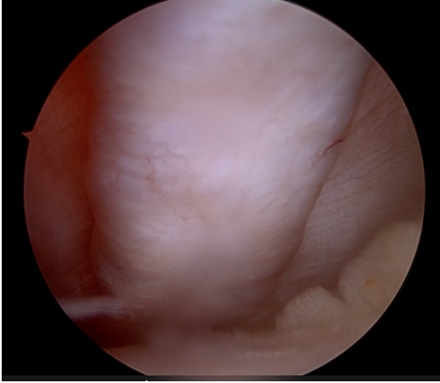

A high anterolateral arthroscopic portal was created for good visualization of the knee joint, and an anteromedial portal was created for instrumentation. A diagnostic arthroscopy was performed. The anterior cruciate and posterior cruciate ligaments were intact and taut. The patient had intact menisci along with healthy cartilage. An osteochondral fragment of the size of 2 cm × 2.5 cm was visualized floating in the joint. This fragment was identified from the posterolateral aspect of the LFC. The patellar facets and ridge were identified and were unremarkable. There were no other positive findings on the diagnostic arthroscopy. The fragment was removed from the anterolateral portal by increasing the incision to a length of 1.5 cm. Fig. 6.

Figure 6: Patella dislocated before medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction – reduced after reconstruction.

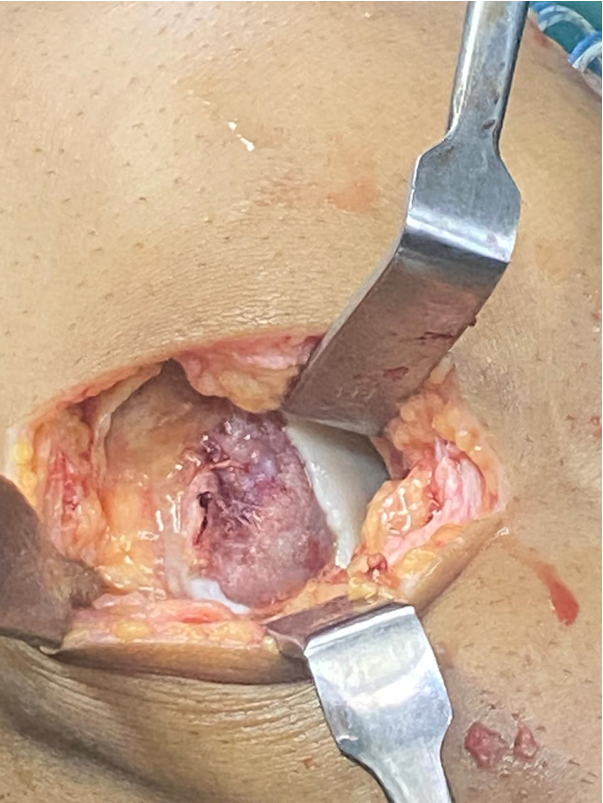

A decision was made according to the size of the fragment and the patellofemoral instability to do an MPFL reconstruction with the hamstring autograft and perform a lateral parapatellar arthrotomy to fix the osteochondral fragment anatomically.

A 2 cm incision was made over the anteromedial aspect of the tibia over the Pes insertion, and the semitendinosus and gracilis tendons were harvested, and the graft was prepared on the back table with a final length of 18 cm. A 4 cm long incision was made on the medial aspect of the femur, and the adductor tubercle was identified. The Schöttles point was identified using fluoroscopy guidance as the anatomic insertion point of the MPFL ligament. A guide wire was placed at this point, and serial reaming was done over this guide wire with a 6 mm drill bit in the anterior and superior direction. A 2 cm long incision was made on the medial aspect of the patella, and dissection was done to identify the medial ridge of the patella. A drill guide for the suture anchors was used to create 2 tunnels to receive the suture anchors on the medial aspect of the patella. These drill holes were drilled under arthroscopic guidance to make sure the drills do not enter the joint and stay extra-articular. 2 × 4 mm double-loaded suture anchors were inserted into the patella drill holes. A tunnel was created inside layer 2 of the medial patello-femoral tissue complex, and the graft was tunneled through this tissue tunnel with the combined limb, along with the femoral fixation endobutton kept at the mouth of the drilled femoral hole and the U-limb of the graft kept near the patella. The graft was locked into place with the double-loaded suture anchors and was tightened securely with locking knots. A thread was passed through the femoral tunnel, and the endobutton was pulled through the tunnel and flipped on the lateral aspect of the distal femur. The graft was tightened in place by pulling on the tensioning threads after flexing the knee to 30° flexion. The position of the patella and tension on the MPFL graft were monitored during the tightening of the graft and were satisfactory post-tightening. Appropriate care was taken to avoid over-tensioning the MPFL and making sure Grade 1 patella glide was present after tightening. A fluoroscopy shot was taken to confirm the position of the endobutton on the cortex of the lateral femur. The knee was flexed to 60° and a 5 cm skin incision was taken along the lateral aspect of the patella, and a lateral parapatellar arthrotomy was performed. An arthroscopic burr was used to freshen the bed of the osteochondral fragment base on the femoral condyle base till fresh bleeding was visualized. The previously removed osteochondral fragment was placed in position under direct vision and was temporarily fixed in a reduced position with two guide pins for headless screws. Two bioabsorbable PLLA pins of diameter 2.7 mm were used to stabilize the fragment after predrilling with the provided drill. The two headless screw guide pins were over-drilled with the help of the drill bit, and two headless screws of length were introduced and fixed. The stability of the fragment was assessed by moving the knee through its range of movement. Fig. 7,8.

Figure 7: Osteochondral defect of lateral femoral condyle.

Figure 8: Lateral femoral condyle post fixation of defect.

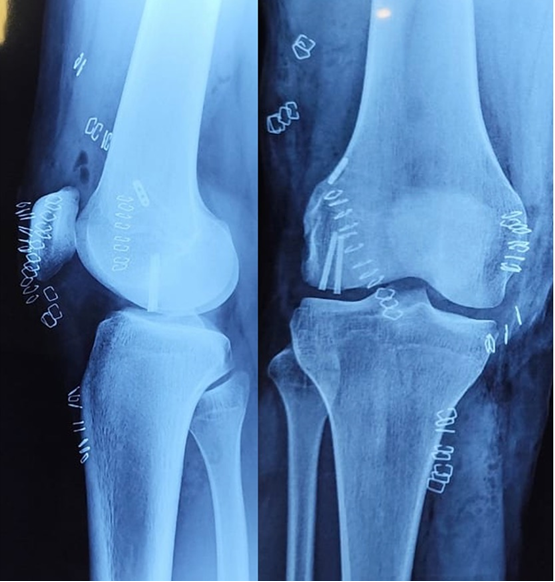

Final tightening of the MPFL graft was done by pulling the tensioning threads. A confirmatory shoot was taken through the fluoroscopy machine to confirm the fragment reduction and the position of the Herbert screws. Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Well tensioned medial patellofemoral ligament graft in situ in layer 2.

The lateral arthrotomy was closed with absorbable Number 1 Polyglactin 910 suture to ensure a watertight closure. The subcutaneous tissue was closed with 2-0 Polyglactin 910 sutures. Skin was closed with skin staplers. Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Immediate post-operative radiographs of the right knee.

The patient was given a compression dressing and a long knee brace post-surgery for the post-operative period. The patient was advised to start knee range of movement exercises from the following day to allow for the lateral arthrotomy not to fibrose and cause excessive lateral tightness. He was advised 4 weeks of non-weight bearing with a walker/crutch and was advised to switch to partial weight bearing after 4 weeks post-surgery. The patient was followed up at 4 weeks to start partial weight bearing and a regular follow-up. He had achieved ROM up to 90° but had developed a 10° flexion deformity. He was advised aggressive physiotherapy, prone extensions, and quadriceps strengthening. He followed up at 6 months with full extension achieved and a range from 0°to 120°. He was still complaining of pain on and off, but had resumed all activities, including playing racquet sports regularly. There were no episodes or any feeling of patellar instability. The osteochondral fragment was holding well and had achieved radiological union. The patient was advised to follow-up at 1 year. Fig. 11.

Figure 11: 6 months follow-up X-ray of the right knee showing healing of the fragment.

Osteochondral fractures (OCFs) associated with acute patellar dislocations are a well-recognized but relatively infrequent occurrence, primarily observed in adolescents. The commonly reported sites for such injuries are the medial patellar facet and the anterolateral aspect of the LFC [4]. However, the occurrence of a large osteochondral fragment arising from the posterior aspect of the LFC following patellar dislocation, especially in an adult, is exceedingly rare. Our case highlights such a presentation in a 20-year-old male, with concurrent complete tear of the MPFL, managed by anatomic fixation of the fragment and MPFL reconstruction using hamstring autograft. The rarity of this injury pattern is emphasized by existing literature. Pettinari et al. described a similar case in a 17-year-old girl, with the osteochondral detachment located at the posterior condyle, a region seldom involved due to its biomechanical position during normal joint articulation [5]. They hypothesized the lesion resulted from a sequence where the dislocated patella, during attempted spontaneous relocation in deep flexion, impacts the posterior LFC–a mechanism possibly replicated in our case, given the patient’s report of continued flexion post-injury. While Bansal et al. coined the term “knee trap-door fracture” for an axial intra-articular LFC split fracture associated with MPFL rupture, our case aligns more with a posterolateral impaction fragment, though both cases share a traumatic patellar instability mechanism and present similar clinical challenges [6].

Another notable feature of our case is the patient’s generalized joint hypermobility (Beighton score 6/9), a known risk factor for patellar instability. Although the patient had no documented history of prior dislocations, his hyperlaxity may have contributed to the severity of injury from what appeared to be a single dislocation event. This raises the consideration that adult patients with constitutional ligamentous laxity may present with injury patterns more typical of adolescents. MRI imaging in our case provided essential insights, confirming the MPFL tear and identifying the precise size and origin of the osteochondral fragment. This influenced our decision to proceed with surgical management, balancing the need for articular surface preservation and patellar stabilization. While fragments smaller than 1 cm2 may be amenable to excision, larger defects–such as in our case measuring 2.5 × 2.5 cm–necessitate fixation to avoid long-term complications such as chondral degeneration or early osteoarthritis. In young patients, cartilage defects <1 cm2 can be left alone, especially if they are in the non-weight-bearing zone. In situations where the fragments are excised piecemeal/crushed or are larger than cm2 and are in the weight-bearing area of the femur, leaving the defect alone is not advisable. If the fragment is amenable to fixation, the best treatment option is fixation with headless screws/bio pins/or the newer suture tape devices, which are made of absorbable polygalactin 910. In cases where the fragment can not be fixed and the defect is in the weight-bearing portion of the joint or on the patella ridge, cartilage procedures are the treatment of choice. These can be done at the index surgery or can be done as a second stage (current recommendation). The defects can be filled with OATS, matrix augmented ACI. For chronic cases of osteochondral defects, the cartilage procedures have favourable outcomes [1,3,7].

A combined approach of arthroscopy and lateral parapatellar arthrotomy enabled accurate localization and fixation of the fragment using headless screws and bioabsorbable pins. This mirrors the technique described by Pettinari et al., who also opted for a dual approach due to limited visualization of the posterior condyle through arthroscopy alone [5]. Moreover, our concurrent MPFL reconstruction using hamstring autograft and suture anchor fixation aligns with best practices for restoring medial patellar restraint, particularly in patients with anatomical risk factors such as increased Insall-Salvati and Caton–Deschamps indices, and elevated TT–TG distance [8,9]. The post-operative protocol in our case emphasized early controlled motion to prevent lateral arthrotomy fibrosis, while maintaining non-weight-bearing status for 4 weeks. This parallels regimens from both comparator reports, which also reported successful clinical outcomes at 6 months–2 years of follow-up with return to sports. [10] In conclusion, this case adds to the limited body of literature documenting posterolateral LFC OCFs associated with patellar dislocation in adults, and supports a management strategy involving fragment fixation combined with MPFL reconstruction. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for such injuries, especially in patients with ligamentous laxity and significant hemarthrosis post-patellar dislocation. A structured surgical approach and timely rehabilitation can yield excellent functional outcomes, as seen in our case.

This case underscores the importance of high clinical suspicion for osteochondral injury in adult patellar dislocation, especially in patients with underlying joint hypermobility or anatomical predispositions. Early diagnosis, detailed imaging, and a combined approach of fragment fixation and MPFL reconstruction can restore knee stability and articular congruity, enabling optimal post-operative recovery and return to activity.

Adult patients with patellar dislocation, particularly those with joint hypermobility, may present with rare osteochondral injuries of the LFC. Early imaging and combined surgical management with fragment fixation and MPFL reconstruction ensure joint preservation and functional recovery.

References

- 1. Seeley MA, Knesek M, Vanderhave KL. Osteochondral injury after acute patellar dislocation in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop 2013;33:511-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Sanders TG, Paruchuri NB, Zlatkin MB. MRI of osteochondral defects of the lateral femoral condyle: Incidence and pattern of injury after transient lateral dislocation of the patella. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2006;187:1332-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Tyler TF, Lung JY. Rehabilitation following osteochondral injury to the knee. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2012;5:72-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Nomura E, Inoue M, Kurimura M. Chondral and osteochondral injuries associated with acute patellar dislocation. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2003;19:717-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Pettinari F, Secci G, Franco P, Civinini R, Matassi F. A rare case of osteochondral fracture of posterior aspect of lateral femoral condyle after patellar dislocation. J Orthop Rep 2023;2:100151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Bansal S, Choudhury AK, Barman S, Niraula BB, Raja BS, Kalia RB. Medial patellofemoral ligament tear associated with an intra-articular axial split osteochondral fracture of the lateral femoral condyle: A “knee trap-door” fracture. J Orthop Case Rep 2023;13:52-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Howell M, Liao Q, Gee CW. Surgical management of osteochondral defects of the knee: An educational review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2021;14:60-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Guerrero P, Li X, Patel K, Brown M, Busconi B. Medial patellofemoral ligament injury patterns and associated pathology in lateral patella dislocation: An MRI study. Sports Med Arthrosc Rehabil Ther Technol 2009;1:17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Migliorini F, Marsilio E, Cuozzo F, Oliva F, Eschweiler J, Hildebrand F, et al. Chondral and soft tissue injuries associated to acute patellar dislocation: A systematic review. Life 2021;11:1360. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Vitale TE, Mooney B, Vitale A, Apergis D, Wirth S, Grossman MG. Physical therapy intervention for medial patellofemoral ligament reconstruction after repeated lateral patellar subluxation/dislocation. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2016;11:423-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]