Skip lesions within the same long bone in giant cell tumors are exceptionally rare and signal aggressive biological behavior, often associated with recurrence and metastasis. Early diagnosis, high clinical suspicion, thorough imaging, and a multidisciplinary approach – including denosumab therapy and surgical reconstruction – are essential for achieving optimal outcomes.

Dr. Rajesh Rana, Department of Orthopaedics, SCB Medical College and Hospital, Cuttack, Odisha, India. Email: rajesh.rana66@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a benign but locally aggressive tumor, commonly affecting the epiphysis of long bones in young adults. Skip lesions in GCT – defined as discontinuous tumor foci within the same bone – are exceedingly rare, particularly in the appendicular skeleton. Simultaneous recurrence and skip lesions in the same bone have been rarely documented.

Case Report: We report a rare case of a 21-year-old female with a recurrent GCT of the proximal femur, previously treated with curettage, bone cementing, and fixation. Two years post-recurrence, she developed a skip lesion in the distal femur along with pulmonary metastases. Management included neoadjuvant denosumab, excision of the proximal lesion with megaprosthesis reconstruction, and curettage and cementation of the distal lesion with plate fixation. Post-operative follow-up showed significant clinical improvement and no recurrence or metastasis progression.

Conclusion: This case highlights an exceptionally rare presentation of recurrent GCT with a skip lesion in the same bone and asymptomatic pulmonary metastases. Early recognition, appropriate imaging, and a multidisciplinary approach – including denosumab therapy and surgical reconstruction – are essential for favorable outcomes in such aggressive and atypical cases.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor of bone, skip lesion, proximal femur, denosumab, megaprosthesis reconstruction.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a benign but locally aggressive neoplasm that predominantly arises in the epiphyseal region of long bones, typically in young adults [1]. Although GCT rarely involves the proximal femur, the development of a skip lesion within the same bone is exceptionally uncommon, with only a few cases reported in the literature [2]. Skip lesions are defined as discrete tumor deposits separated by areas of normal bone, signifying an aggressive form of the disease [3]. Recurrent GCT is reported in approximately 10–25% of cases, often necessitating more intricate treatment approaches [4]. However, the occurrence of skip lesions in GCT remains sparsely documented, particularly in the appendicular skeleton. Most reported cases involve the axial skeleton or atypical sites [5].

Simultaneous recurrence in the proximal femur and a skip lesion in the distal femur is an exceptionally rare phenomenon, emphasizing the clinical uniqueness and significance of such cases. This case highlights the rare presentation of skip lesions in GCT and the associated challenges in diagnosis and management. By sharing this report, we aim to expand the current understanding of the clinical and pathological behavior of GCT with skip lesions, contributing valuable insights for early detection and effective treatment planning.

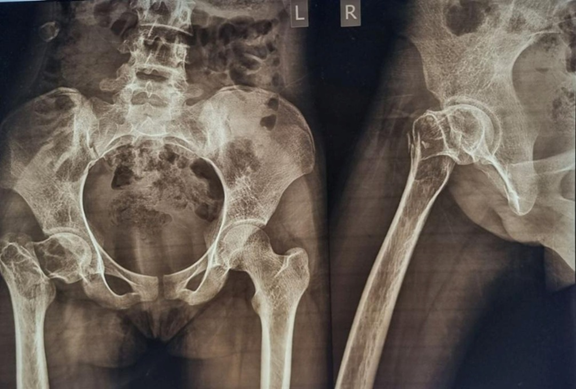

A 21-year-old female presented with complaints of pain and swelling in the right proximal thigh and hip, accompanied by an inability to bear weight. The patient had been apparently well 4 years earlier when she sustained a pathological fracture of the proximal femur and was diagnosed with a GCT (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Giant cell tumor involving the neck region of the femur with pathological fracture.

Figure 1: Giant cell tumor involving the neck region of the femur with pathological fracture.

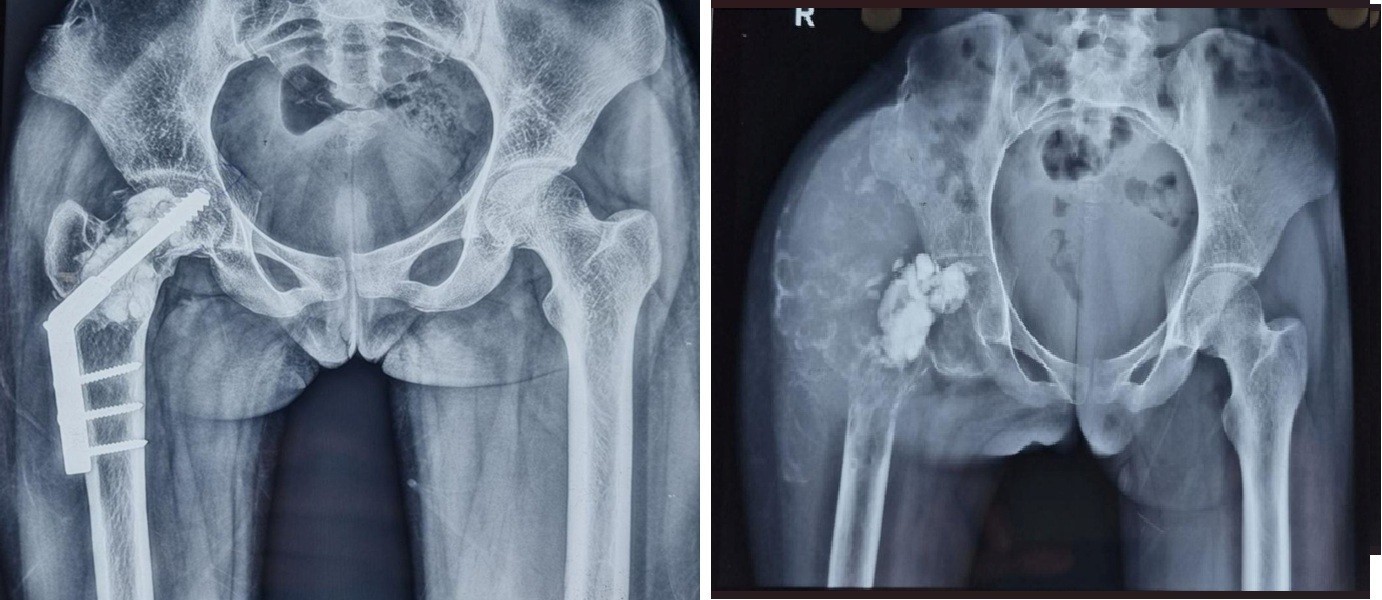

She underwent surgery involving curettage, bone cement filling, and dynamic hip screw fixation at another institution (Fig. 2). However, the patient experienced a recurrence of the tumor 2 years later, prompting removal of the implant by the primary surgeon.

Figure 2: Initial treatment included curettage, cement filling, and dynamic hip screw fixation. Following tumor recurrence, the implant was removed.

Figure 2: Initial treatment included curettage, cement filling, and dynamic hip screw fixation. Following tumor recurrence, the implant was removed.

Two years after that, the patient presented to our institution. The primary symptoms included pain and swelling in the proximal femur, and the patient was ambulating with support due to her inability to bear full weight on the right leg. On examination, the proximal thigh exhibited a large, diffuse swelling with a 10 cm scar over the lateral aspect. The swelling was tender, had a variegated consistency and irregular borders, and was immobile and fixed to the underlying bone. The margins were ill-defined.

Blood investigations revealed elevated lactate dehydrogenase levels and a positive tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase test, signifying the aggressiveness of the tumor. The patient also had reduced hemoglobin levels. Radiographic evaluation revealed diffuse swelling of the proximal femur characterized by a mix of osteoblastic and osteolytic zones extending to the epiphyseo-metaphyseal region. The femoral head exhibited significant destruction, accompanied by notable soft-tissue involvement. A “soap-bubble” appearance was apparent, with radio-dense material in situ, indicative of remnant bone cement. The chest radiograph was normal.

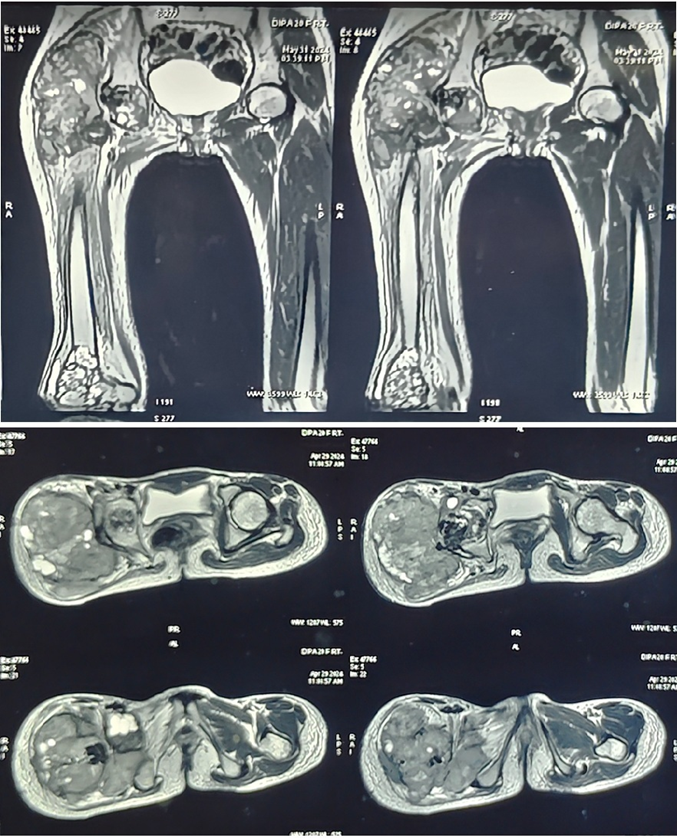

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a large, inhomogeneous, expansile, and infiltrative lesion measuring 12.3 × 14.9 × 12.1 cm, involving the right hip joint and surrounding periarticular tissues. The lesion infiltrated adjacent soft-tissue structures and caused significant erosion of the femoral head. Residual bone cement material was also evident, indicating recurrence (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging showing a large tumor at the proximal femur, along with a skip lesion at the distal femur.

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging showing a large tumor at the proximal femur, along with a skip lesion at the distal femur.

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the thorax revealed multiple parenchymal and pleural-based lesions in both lung fields, consistent with metastatic disease. Core needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of a GCT. The tumor was classified as Enneking Stage III malignant GCT.

The distal femur exhibited an osteolytic lesion with a characteristic “soap-bubble” appearance. The patient was asymptomatic with regard to this lesion. Radiologically, the lesion showed epiphyseo-metaphyseal extension and was well-contained without any cortical breach. MRI findings also suggested a likely GCT. A core needle biopsy confirmed the diagnosis. Neoadjuvant denosumab, a RANKL inhibitor, was administered subcutaneously at a dose of 120 mg on days 1, 8, 15, and 28, followed by maintenance doses at 4-week intervals for a total of six doses. This pre-operative treatment regimen resulted in the formation of adequate surgical margins. Notably, denosumab therapy enabled surgical resection of the previously unresectable tumor.

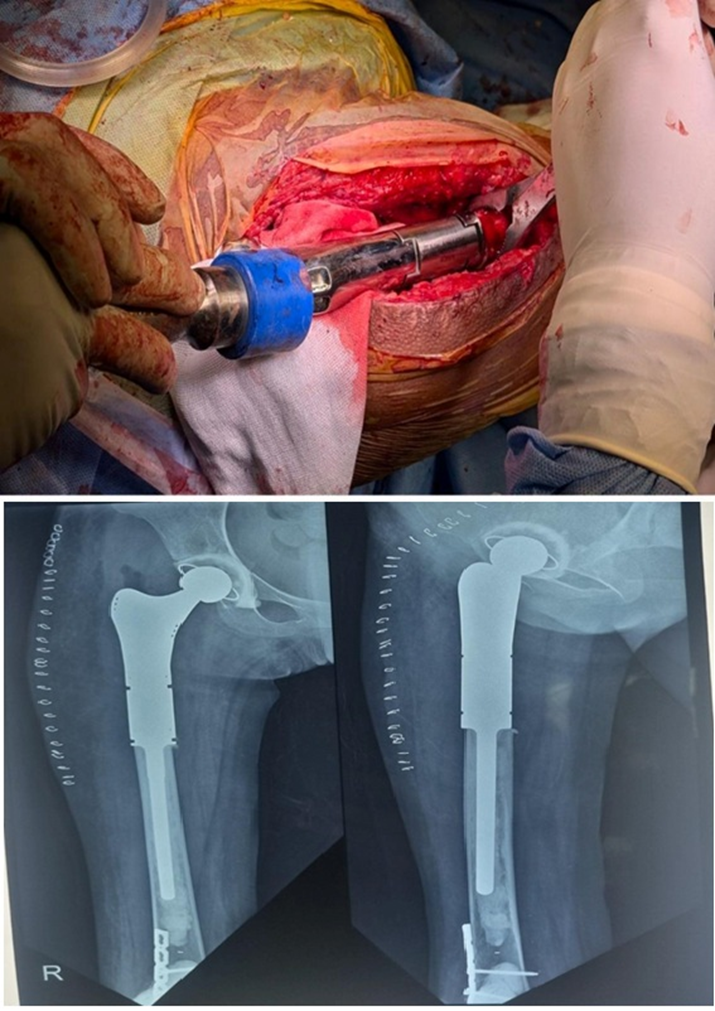

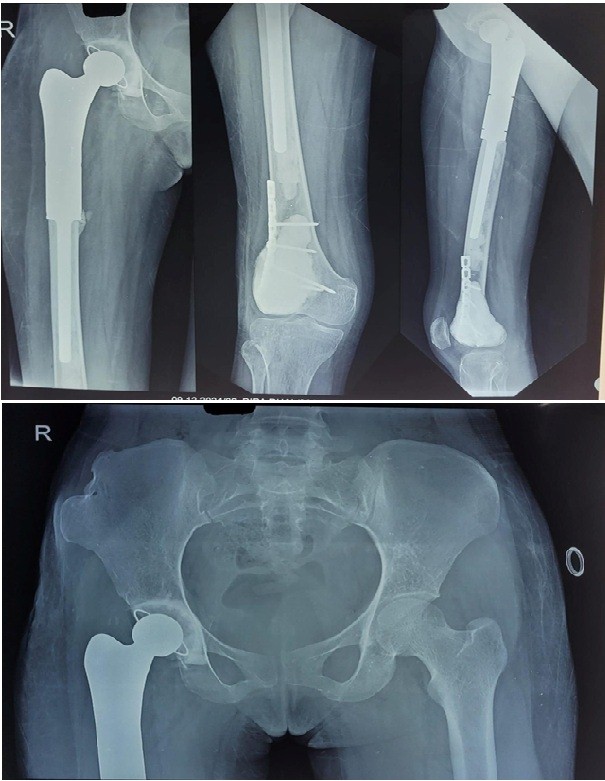

The proximal femoral GCT was excised and reconstructed using a proximal femoral mega prosthesis (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Mega prosthesis of the proximal femur after excision of the tumor.

Figure 4: Mega prosthesis of the proximal femur after excision of the tumor.

Figure 5: Curettage and bone cement filling of the distal femur skip lesion with supplementary fixation.

Figure 5: Curettage and bone cement filling of the distal femur skip lesion with supplementary fixation.

The distal femoral lesion was treated with curettage and bone cement filling (Fig. 5). In addition, a plate was applied at the distal femur for reinforcement. The patient was allowed to bear weight with a walker 21 days postoperatively. Gradually, she demonstrated significant clinical improvement, regaining the ability to bear weight without pain or support. A repeat HRCT of the chest showed regression of the small lesions. Postoperatively, denosumab was continued for 4 months as a monthly dose. Follow-up imaging over 12 months revealed no evidence of recurrence, and laboratory parameters remained within normal limits (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: 1-year follow-up of the case showing no recurrence with good fixation.

Figure 6: 1-year follow-up of the case showing no recurrence with good fixation.

This report highlights a rare case of recurrent GCT of the proximal femur with a skip lesion in the distal femur and synchronous pulmonary metastases. The major strengths of this case include detailed diagnostic work-up with imaging and biopsy, and a successful multidisciplinary treatment strategy involving neoadjuvant denosumab, megaprosthesis reconstruction, and cement curettage with fixation. Limitations include relatively short follow-up and the lack of molecular testing, such as H3F3A mutation analysis, which could have strengthened diagnostic accuracy and predicted biological behavior [6].

Skip lesions in GCT are exceedingly rare, with most reports limited to multicentric GCTs or lesions in the axial skeleton [7]. Wirbel et al. reported that multifocal GCTs account for <1% of cases, with true skip lesions within the same long bone being almost anecdotal [8]. GCT typically presents as a solitary, locally aggressive tumor in young adults, most commonly involving the distal femur, proximal tibia, or distal radius [9]. Pulmonary metastases occur in 1–9% of cases and are usually indolent and asymptomatic [10]. In our case, the lung lesions were detected only on HRCT and responded to systemic therapy.

Denosumab, a RANKL inhibitor, has emerged as a valuable neoadjuvant agent in GCT of bone. It reduces osteoclast-like activity, induces calcification, and facilitates surgical resection in unresectable or recurrent tumors [11,12]. Our use of denosumab resulted in effective tumor downstaging, allowing limb-sparing surgery. The skip lesion may have resulted from iatrogenic spread during previous intramedullary instrumentation or intraosseous dissemination via the medullary canal. Despite the biologically aggressive nature suggested by multifocal lesions and metastases, a favorable outcome was achieved with timely diagnosis, targeted therapy, and surgical intervention.

Skip lesions in GCT of bone, especially within the same long bone, are exceedingly rare and signal a more aggressive biological behavior. Their presence – along with asymptomatic pulmonary metastases – necessitates high clinical suspicion, thorough imaging, and timely biopsy. A multidisciplinary strategy incorporating neoadjuvant denosumab, wide excision with megaprosthesis reconstruction, and cement-based curettage can result in effective disease control and good functional outcomes. Vigilant follow-up is essential to detect recurrence or metastasis early.

Giant cell tumor of bone presenting with a skip lesion in the same long bone and silent pulmonary metastases is a rare but aggressive entity. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion in recurrent cases and ensure comprehensive imaging of the entire bone and chest. A multidisciplinary treatment strategy involving denosumab and surgical reconstruction can lead to favorable functional and oncological outcomes.

References

- 1. Sobti A, Agrawal P, Agarwala S, Agarwal M. Giant cell tumor of bone – an overview. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2016;4:2-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Hakozaki M, Tajino T, Yamada H, Hasegawa O, Tasaki K, Watanabe K, et al. Radiological and pathological characteristics of giant cell tumor of bone treated with denosumab. Diagn Pathol 2014;9:111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Nagarajan S, Kathirvelu G, Jaganathan D. Unusual sites of giant cell tumor of bone. Indian J Musculoskelet Radiol 2023;5:128-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Pitsilos C, Givissis P, Papadopoulos P, Chalidis B. Treatment of recurrent giant cell tumor of bones: A systematic review. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:3287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Park YS, Lee JK, Baek SW, Park CK. The rare case of giant cell tumor occuring in the axial skeleton after 15 years of follow-up: Case report. Oncol Lett 2011;2:1323-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Cleven AH, Höcker S, Briaire-De Bruijn I, Szuhai K, Cleton-Jansen AM, Bovée JV. Mutation analysis of H3F3A and H3F3B as a diagnostic tool for giant cell tumor of bone and chondroblastoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:1576-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Hoch B, Inwards C, Sundaram M, Rosenberg AE. Multicentric giant cell tumor of bone. Clinicopathologic analysis of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1998-2008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Wirbel R, Blümler F, Lommel D, Syré G, Krenn V. Multicentric giant cell tumor of bone: Synchronous and metachronous presentation. Case Rep Orthop 2013;2013:756723. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Varga PP, Lazary A. Giant Cell Tumor (Osteoclastoma). Essentials of Spine Surgery; 2024. p. 347-52. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/nbk559229 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Trovarelli G, Rizzo A, Cerchiaro M, Pala E, Angelini A, Ruggieri P. The evaluation and management of lung metastases in patients with giant cell tumors of bone in the denosumab era. Curr Oncol 2024;31:2158-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Borkowska AM, Szumera-Ciećkiewicz A, Szostakowski B, Pieńkowski A, Rutkowski PL. Denosumab in giant cell tumor of bone: Multidisciplinary medical management based on pathophysiological mechanisms and real-world evidence. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:2290. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Li H, Gao J, Gao Y, Lin N, Zheng M, Ye Z. Denosumab in giant cell tumor of bone: Current status and pitfalls. Front Oncol 2020;10:580605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]