Orthopedic surgeons play a vital role in identifying red flags, initiating appropriate investigations, and referring patients to specialized centers for definitive biopsy, staging, and multidisciplinary care in adolescents with suspicious bone lesions.

Dr. Varun Sanap, Department of Surgical Oncology, National Cancer Institute, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: vss1995.vs@gmail.com

Introduction: The “Whoops Procedure” first described by Giuliano and Eilber [1] in 1985 is the unplanned sarcoma resection refers to an unplanned sarcoma resection, where a lesion presumed to be benign is inadvertently excised, only to later be diagnosed as malignant. This leads to higher risks of local recurrence, lower limb salvage rates, and poor functional outcomes. Osteosarcoma, the most common primary bone cancer in adolescents, requires meticulous pre-operative evaluation to prevent inadvertent contamination and ensure optimal treatment.

Case Report: We present a case of a 13-year-old girl who initially underwent curettage and intramedullary nailing for a suspected aneurysmal bone cyst of the proximal femur. Post-operative wound complications and persistent discharge prompted further evaluation, revealing a diagnosis of osteosarcoma. Due to medullary contamination from the prior surgery, limb salvage was not feasible, necessitating a total femur replacement with a modular prosthesis following perioperative chemotherapy. The procedure involved meticulous dissection, preservation of neurovascular structures, and reconstruction using customized titanium alloy prosthesis. The patient had an uneventful recovery with early mobilization and rehabilitation.

Discussion: Total femur replacement is a rare but necessary procedure in cases of extensive tumor involvement, especially after inadvertent contamination. Proper pre-operative planning, including imaging and biopsy by an experienced surgeon, is critical to avoid such complications. Advances in prosthetic design, including modular implants and enhanced fixation techniques, have improved functional outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach involving oncologists, orthopedic surgeons, and pathologists is essential for optimal management.

Conclusion: This case highlights the critical role of early biopsy and specialized care in bone tumor management. The “Whoops Procedure” should be avoided through thorough pre-operative assessment. When faced with extensive contamination, total femur replacement remains a viable solution, offering good functional outcomes with proper surgical planning and rehabilitation.

Keywords: Whoops excision, osteogenic sarcoma, total femur replacement, modular prosthesis.

Benign lesions of the Bone are far more common than malignant lesions and hence surprises that on pathology, lesions turning out to be malignant are also common. Whoops procedure is nothing but an unplanned sarcoma resection. That means when a mass that is assumed to be benign-looking is resected/curetted and the final pathological diagnosis comes out to be malignant. It leads to lower rates of limb salvage, lower rates of local control, and worst functional outcome with shorter mean time to local recurrence [2,3]. Biopsy before going ahead with surgery is the key to reduce inadvertent sarcoma resection [4,5]. Iatrogenic describes negative effects or complications that arise as a result of medical treatments or procedures. These unintended consequences occur despite the intent to diagnose or treat, reflecting inherent healthcare risks. Osteosarcoma is the most common bone cancer in adolescents [6]. Bony lesions in adolescent should be treated with caution with keeping a very high suspicion for malignancy. Osteosarcoma treated as Surgery with perioperative chemotherapy [7]. Surgery required will be wide excision of the tumor with usually single joint arthroplasty and total femur replacement was rarely required. Better results with surgery have been shown when performed in a high-volume center or center of excellence. Total femur replacement is one of the rare surgeries performed, in which a diaphyseal stem joins total hip arthroplasty (THA) and total knee arthroplasty implants-was performed for sarcoma [8]. Osteosarcoma being one of the most common indication for total femur replacement with rarely being done for benign cases and some cases for mechanical prosthesis failure [9,10,11].

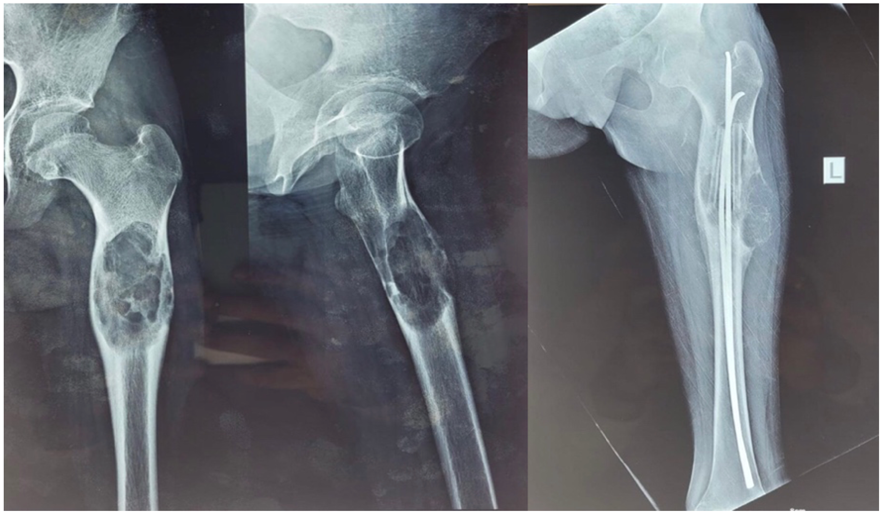

This case report follows a 13-year-old girl who present with pain in the left hip region for 2 months along with difficulty in walking. No associate significant contributory history. Radiograph was s/o a solid cystic lesion on the proximal femur. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast scan of left thigh with femur done s/o well marginated expansile altered signal intensity lesion in proximal diaphysis of left femur with few cystic changes within with break and thinning of cortex at places with periosteal reaction around the lesion. Core biopsy was done s/o Aneurysmal Bone Cyst for which she undergone curettage of bony cyst with bone grafting (fibula) with Intra-Medullary nailing as shown in Fig. 1. Post-operatively she developed fever with wound gets infected with some discharge. Treated with higher antibiotics and daily cleaning and dressing. Fever subsided but continuous discharge from wound present.

Figure 1: Pre-operative Radiograph showing a multicasting lesion in the left proximal femur, Radiograph of post-curettage with fibula grafting with nailing.

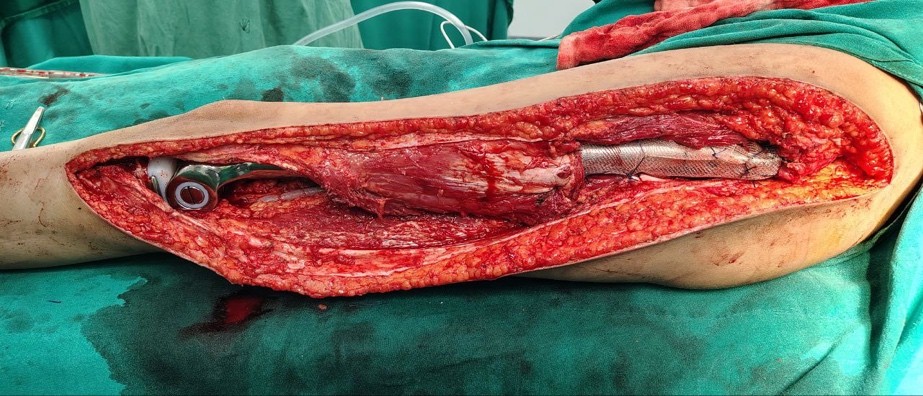

The patient came to us for a second opinion, where we reevaluated from the beginning, with an incisional biopsy done from the wound. It came out to be Osteosarcoma. MRI left lower limb was done to see the local extent. Positron emission tomography (PET) scan was done to rule out distant metastasis. Case discussed in multidisciplinary tumor board and decision taken to go ahead with Perioperative Chemotherapy with surgery. As planned patient given two cycles of Methotrexate, Adriamycin, Cisplatin over 10 weeks. As decided in the multidisciplinary tumor board surgery was planned for her. Due to intramedullary nailing whole femur medullary cavity was contaminated and it was not possible to save distal femur. Surgery planned was a wide excision tumor with left total femur excision with total femur replacement with modular prosthesis reconstruction. Customized prosthesis was made measuring length of the femur shaft and diameter of the femur head. A lateral longitudinal incision was planned to include previous surgery scars. Started caudally with isolating the popliteal artery, popliteal vein, and tibial and common peroneal nerve at the popliteal fossa, proximally, all were traced till their exit from Hunter’s canal. Proximally vastus lateralis was partially sacrificed as the scar of previous surgery was passing through it. The caudal insertion of the gluteus maximum was detached from the femur shaft. Sciatic nerve preserved as shown in Fig. 2. Medially all muscles detached from femur. Disarticulation of knee joint done first followed by hip disarticulation. Specimen delivered with intact scars with it as seen in Fig. 3.

Figure 2: Tumor bed post-resection of total femur.

Figure 3: Resected specimen of total femur with excision of previous surgery scars.

Prosthesis parts were assembled after confirming the length of the excised femur. Proline Mesh fixation over the prosthesis was done, where the upper end of the vastus lateralis and the femoral attachment of the gluteus maximum were sutured to mesh. Abductors of the hip joint are sutured to the implant through mesh, as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Modular prosthesis with meshoplasty.

Post-operative course was uneventful with drain removed on post-operative day 3 and PT discharged on post-operative day 5. Abductor muscle strengthening exercises started on bed on post-operative day 2 without weight bearing. Post-operative X-ray showing well fitted prosthesis as shown in Fig. 5. Four weeks bed rest given for healing of mesh then started full-weight-bearing mobilization with walker f/b stick support and then without support. Strengthening and range of motion exercise titrated for individual need. Past follow-up was in June 2025. As patient attained menarche there will be low chance of limb length discrepancy, but even if occurred can be managed conservatively by shoe lift. Follow-up will be 6 monthly with radiograph of local site for recurrence with contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) thorax for metastasis.

Figure 5: Post-surgery X-ray.

A total femur replacement is a complex orthopedic surgical procedure in which the entire femur is replaced with a prosthetic implant. This surgery is typically performed in cases where the femur is severely damaged or diseased, and other treatments, such as partial replacements, internal fixation, or limb-sparing surgeries are not viable options. Common Reasons for Total Femur Replacement are mainly Bone Tumors, particularly in cases of malignant bone tumors, such as osteosarcoma. Severe Trauma, such as fractures that are too complex to repair or that have resulted in non-union (where the bone does not heal properly), Infection, such as chronic osteomyelitis (bone infection) that has destroyed the bone, will likely require Total femur replacement. Furthermore, Failed Previous Surgeries became a common indication where other treatments, such as hip or knee replacements have failed, leading to complications lead to Total Femur Replacement [12]. Pre-operative planning is a very important aspect in terms of better results. It includes a thorough History and physical Examination, which includes assessment of the patient’s overall health and specific issues related to the affected limb. This must include checking the range of motion, muscle strength, and neurovascular status of the limb. Basic blood investigations and Detailed imaging is critical for planning specifically in cases of malignancy which includes X-rays: Standard X-rays of the femur, hip, and knee are taken to assess the bone structure and extent of damage, a CT scan provides a detailed cross-sectional view of the femur, helping in assessing the extent of bone loss or deformity also helps in biopsy planning, MRI is useful to determine involvement of soft tissue component and involvement of bone marrow [13]. A biopsy is a crucial step in diagnosing osteosarcoma, particularly in the proximal femur. When imaging studies (X-rays, CT scans, MRIs) suggest a malignant bone tumor, a biopsy is performed to confirm the diagnosis, and it will provide tissue for HPE, allowing pathologists to determine the exact type of tumor, its grade, and any specific molecular characteristics. Most commonly, Core Needle Biopsy is performed from the periphery of the lesion, where there will be actively dividing tumor cells. Furthermore, this should be performed by a surgeon who is going to do the primary surgery. The goal is to perform the biopsy in a manner that preserves all future surgical options. The biopsy incision should be placed along a path that could be incorporated into the definitive surgical resection [4,5]. Any bony lesion with a solid component must be biopsied before going for any surgical intervention, as in our case biopsy was done, but the orthopedician must have kept a low suspicion for malignancy, leading to curetting and putting an IM nail, which has led to contamination of the whole medulla and subsequently total femur replacement. The role of pathologist is also of prime importance and the pathologist ensures that the tissue samples are handled and processed correctly, which is critical for accurate diagnosis. Any errors in this process could lead to misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment. Second opinion can be taken in complex or ambiguous cases; the pathologist may consult with colleagues or seek a second opinion to ensure the most accurate diagnosis possible, which is vital in guiding the patient’s treatment plan. Overall, the pathologist’s role in the histopathological examination of osteosarcoma is integral to accurate diagnosis, treatment planning, prognostication, and overall patient care. Their expertise ensures that each patient receives the most appropriate and effective treatment based on a thorough understanding of the tumor’s characteristics. Planning for prosthesis is also of great importance. Different prostheses have been designed, first being Buchman [14] who introduced a customized femoral prosthesis made from cobalt-chromium-molybdenum alloy. The design of total femoral prostheses has advanced significantly alongside developments in biomaterials. Initially, prostheses were homemade, but over time, they evolved into custom-made and then modular designs [15,16,17]. Nowadays, patients can receive modular prostheses immediately, tailored to their specific needs without the need for a lengthy manufacturing process. The materials used have also improved, shifting from titanium nitride and stainless steel to more advanced titanium alloys. In this particular patient, customized titanium alloy prosthesis was designed using bilateral total femur X-rays, with the prosthesis length matched to the healthy leg or made slightly shorter by 1–2 cm. The femoral head was similarly measured, and a bipolar artificial femoral head was recommended to reduce the risk of hip joint dislocation. A rotating hinge knee joint was used to minimize the chance of knee prosthesis loosening. Recently, new types of total femoral prostheses have been developed. Traditional total femoral replacement often compromises muscle attachment points, leading to poor limb function and frequent hip dislocations post-surgery. To address this, Ward et al. [18] and Gorter et al. [19] developed an intramedullary femoral prosthesis that preserves certain muscle and bone attachment points, thereby enhancing limb stability, reducing the risk of dislocation, and lowering the incidence of incision infections. In addition, to address leg length discrepancies in pediatric patients after total femoral replacement, Schindler et al. [20] designed an extendable prosthesis. To combat deep infections and abscesses post-surgery, Glehr [21] introduced a silver ion-coated femoral prosthesis, which has shown promise in reducing post-operative infection rates.

The “Whoops Procedure,” first described by Giuliano and Eilber in 1985 is the unplanned sarcoma resection, underscores the importance of thorough pre-operative evaluation, especially in adolescents with suspicious bone lesions. General orthopedicians play a vital role in identifying red flags, initiating appropriate investigations, and referring patients to specialized centers for definitive biopsy, staging, and multidisciplinary care. Accurate biopsy by an experienced surgeon is essential to avoid contamination and ensure optimal treatment planning. In cases like osteosarcoma, medullary contamination may necessitate complex surgeries, such as total femur replacement, which require meticulous planning and execution. Collaboration among oncologists, surgeons, and pathologists is crucial for achieving the best outcomes. With advancements in prosthetic design and surgical techniques, patients now have better functional recovery and improved quality of life after such procedures.

Early suspicion, accurat, and timely referral to specialized centers are critical to avoid unplanned sarcoma surgeries and enable optimal outcomes in adolescent bone tumors.

References

- 1. Giuliano AE, Eilber FR. The rationale for planned reoperation after unplanned total excision of soft-tissue sarcomas. J Clin Oncol 1985;3:1344-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Marcove R, Lewis MM, Rosen R, Huvos AG. Total femur and total knee replacement. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977;126:47-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Fountain JR, Dalby-Ball J, Carroll FA, Stockley I. The use of total femoral arthroplasty as a limb salvage procedure: The Sheffield experience. J Arthroplasty 2007;22:663-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Hoell S, Butschek S, Gosheger G, Dedy N, Dieckmann R, Henrichs M, et al. Intramedullary and total femur replacement in revision arthroplasty as a last limb-saving option: Is there any benefit from the less invasive intramedullary replacement? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:1545-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Clement ND, MacDonald D, Ahmed I, Patton JT, Howie CR. Total femoral replacement for salvage of periprosthetic fractures. Orthopedics 2014;37:789-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Ayerza MA, Muscolo DL, Aponte-Tinao LA, Farfalli G. Effect of erroneous surgical procedures on recurrence and survival rates for patients with osteosarcoma. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2006;452:231-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Wang TI, Wu PK, Chen CF, Chen WM, Yen CC, Hung GY, et al. The prognosis of patients with primary osteosarcoma who have undergone unplanned therapy. Jpn J Clin Oncol 2011;41:1244-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Pakos EE, Nearchou AD, Grimer RJ, Koumoullis HD, Abudu A, Bramer JA, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes for osteosarcoma: An international collaboration. Eur J Cancer 2009;45:2367-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Bickels J, Jelinek JS, Shmookler BM, Neff RS, Malawer MM. Biopsy of musculoskeletal tumors. Current concepts. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;368:212-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Bickels J, Malawer MM. 2 biopsy of musculoskeletal tumors. Oper Tech Orthop Surg Oncol 2012;25-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Eilber F, Giuliano A, Eckardt J, Patterson K, Moseley S, Goodnight J. Adjuvant chemotherapy for osteosarcoma: A randomized prospective trial. J Clin Oncol 1987;5:21-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Murray J, Jeyapalan R, Davies M, Sheehan C, Petrie M, Harrison T. Total femoral arthroplasty for non-oncological indications. Bone Joint J 2023;105-B:888-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Ramanathan D, Siqueira MB, Klika AK, Higuera CA, Barsoum WK, Joyce MJ. Current concepts in total femoral replacement. World J Orthop 2015;6:919-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Buchman J. Total femur and knee joint replacement with a vitallium endoprosthesis. Bull Hosp Joint Dis 1965;26:21-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Present DA, Kuschner SH. Total femur replacement. A case report with 35-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990;251:166-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Hu QT, Jiang QW, Su GL, Shen JZ, Shen X. Total femur and adjacent joint replacement with endoprosthesis: Report of 2 cases. Chin Med J (Engl) 1980;93:86-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Steinbrink K, Engelbrecht E, Fenelon GC. The total femoral prosthesis. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1982;64:305-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Ward WG, Dorey F, Eckardt JJ. Total femoral endoprosthetic reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1995;316:195-206. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Gorter J, Ploegmakers JJ, Ten Have BL, Schreuder HW, Jutte PC. The push-through total femoral prosthesis offers a functional alternative to total femoral replacement: A case series. Int Orthop 2017;41:2237-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Schindler OS, Cannon SR, Briggs TW, Blunn GW, Grimer RJ, Walker PS. Use of extendable total femoral replacements in children with malignant bone tumors. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1998;357:157-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Glehr M, Leithner A, Friesenbichler J, Goessler W, Avian A, Andreou D, et al. Argyria following the use of silver-coated megaprostheses: No association between the development of local argyria and elevated silver levels. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:988-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]