Atypical lipomatous tumor/well-differentiated liposarcoma if recurs has chances to get transformed in to dedifferentiated liposarcoma which has metastatic potential so it should be treated by its expert multidisciplinary team and first surgery is very important and should provide adequate disease clearance.

Dr. Ashwin Prajapati, Department of Orthopedic Oncology, Marengo CIMS Cancer Centre, CIMS Road, Off Science City Road, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. E-mail: ashwinprajapatitmc@gmail.com

Introduction: Soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) being a rare malignancy, many times it undergoes inadequate surgery at first instance, leading to higher chances of recurrence. Atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT)/well-differentiated liposarcoma frequently undergoes first inadequate surgery leading to higher recurrence rate and sometimes getting converted to higher grade malignancy like dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

Case Report: We had a 63-year-old female who presented with recurrent huge (dimension on final histopathology report: 29 × 24 × 11 cm) ALT of thigh after three prior surgeries over the span of 8 years. We resected it with wide margins and did a prophylactic nailing at second stage. Final histopathology report came out to be liposarcoma with foci of low-grade dedifferentiation (FNCLCC Grade 3). Patient received post-operative radiotherapy. At final follow-up of 35 months, our patient is recurrence free, doing all her daily routine activity independently.

Conclusion: Ten percentages of the ALT dedifferentiate into dedifferentiated liposarcoma, which has 15–20% metastatic potential compared to almost nil in ALT which happened in our case. Due to this, we recommend treatment of ALT and all STS at a tertiary cancer care center by a multidisciplinary team as it requires adjuvant treatment also apart from surgery with adequate margins.

Keywords: Atypical lipomatous tumor, liposarcoma, soft-tissue sarcoma multidisciplinary team, recurrent alt, prophylactic nailing soft-tissue sarcoma.

Soft-tissue sarcoma (STS) comprises only 1% of all malignancies [1] still having 50 histological subtypes [2] each carrying different diagnostic and therapeutic implications. Due to its rarity and lack of awareness, many times it is undertreated in form of adequacy of surgery and adjuvant treatment. Liposarcoma is one of the common STS comprising around 15% all STSs [3]. It has five distinct histologic subtypes: Atypical lipomatous tumor (ALT)/well-differentiated, dedifferentiated, myxoid, pleomorphic, and mixed [3]. They are diverse in their clinical and biological behavior, ranging from non-metastatic tumors with very indolent course (well-differentiated liposarcoma) to tumors with high metastatic potential and very aggressive course (pleomorphic liposarcoma) [3]. We had 63-year-old female with huge 3rd time recurrent ALT/well-differentiated liposarcoma involving skin, a large segment of femoral vessels and periosteum of femur which eventually turned out to be dedifferentiated liposarcoma.

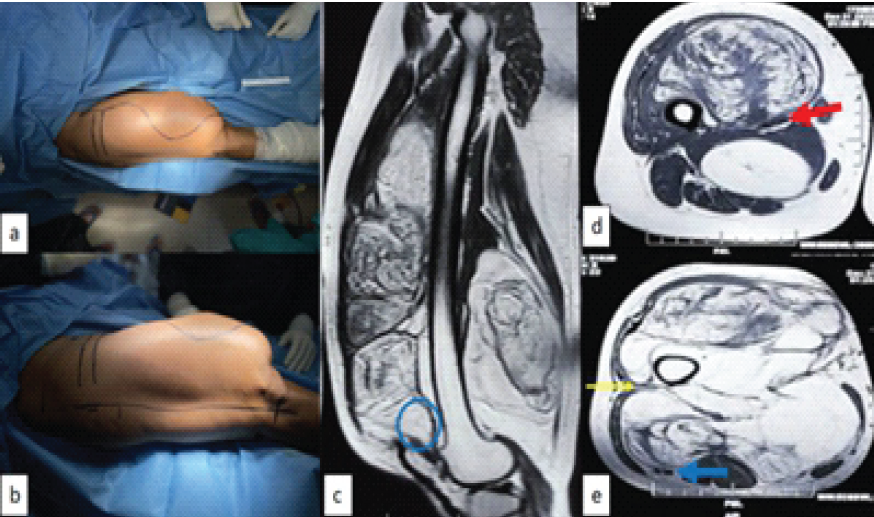

A 63-year-old female presented with huge, painless swelling in thigh (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Intraoperative picture of thigh and pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (a) superior view showing medial incision sacrificing medial skin and islanding out all previous surgical and biopsy scars, (b) lateral view showing lateral incision, (c) MRI with sagittal image showing proximity to femur and tumor extent up to suprapatellar pouch (blue round), (d) axial section through proximal part of tumor showing vessels (red arrow) lying between two parts of the tumor, and (e) axial section through distal part showing vicinity of tumor with sciatic nerve (blue arrow) and only virgin plane (yellow arrow) through which femur can be reached.

She had history of excision of mass 8, 4, and 2 years back. All post-surgery specimens were reported as ALT/well-differentiated liposarcoma (ALT). She underwent radiological investigation in form of local radiograph and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). On radiograph, tumor was scalloping femur cortex without involving it. On MRI, it measured 147 × 102 × 263 mm (antero-posterior × transverse × cranio-caudal) and it was involving all compartments of thigh, femoral vessels, and encircling femur almost 360° at some places. Computed tomography (CT) scan was done, in addition, to confirm that there was no erosion of femur cortex. Patient had two previous surgical scars. Biopsy was done from most heterogeneous area on MRI which was reported as well-differentiated liposarcoma. Systemic staging was done in form of ultrasound of bilateral groin and high-resolution CT thorax which did not show any disease [4].

Planning

Two skin incisions

First on medial side, fusiform incision islanding out previous surgical and biopsy scars. Second on lateral aspect, straight on lateral intermuscular septum (Fig. 1).

Muscles

Rectus femoris, semitendinosus, semimembranosus, long head of biceps femoris, and part of vastus lateralis to be salvaged rest all thigh muscles to be sacrificed. Medial patella retinaculum to be sacrificed.

Vessels

Part of superficial femoral vessels inside the tumor (Fig. 1) to be sacrificed and reconstructed with polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) graft. Profunda femoris to be sacrificed without reconstruction.

Nerves

Sciatic nerve to be saved (Fig. 1).

Bone

Periosteum of femur will be taken as margin at all sites, where tumor is close to the bone (Fig. 1).

Prophylactic nailing

As a second step surgery, as we were anticipating post-operative radiotherapy, patient was elderly female and we were sacrificing periosteum of femur to great extent [5,6].

Surgical steps

Patient positioned supine on table and supported from all sides to allow maximum tilting of the table to facilitate exposure of thigh from all sides. Skin incisions marked as described in planning (Fig. 1). Bony prominence, that is, greater trochanter, lateral joint line, and patella, was identified and marked for measurement.

First medial dissection done. The saphenous vein was saved. Sartorius retracted and superficial femoral vessels identified and dissected until it was going in to the tumor and isolated with vascular tape. Profunda femoris vessels identified and ligated, where it was entering the tumor. All adductor muscles cut at that level. Rectus femoris dissected away from the tumor and saved. Whole of the vastus intermedius and medialis sacrificed and kept on tumor as margin.

Lateral dissection started. Part of vastus lateralis saved and lateral intermuscular septum cut to enter the posterior compartment. Short head of biceps femoris kept on tumor as margin and long head saved. Sciatic nerve identified, dissected off the tumor, and retracted posteriorly. Distally medial patella retinaculum cut and tumor freed from distal attachment. Femoral vessels identified in popliteal fossa coming out of the tumor and isolated with vascular tape.

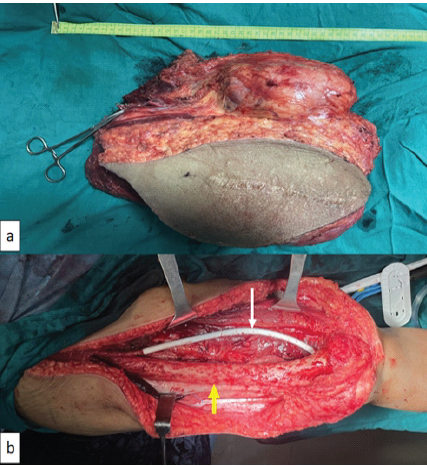

Tumor was erased from femur starting from lateral side and coming to medial side. Femoral vessels ligated and cut proximal and distal to the tumor. Specimen delivered out severing its rest of the attachment. Specimen measured 6.5 kg and there was a muscle or a free glistering white fascia (which makes 2 cm of qualitative margin) [7] all around (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Resected specimen and intraoperative image after vessels reconstruction; (a) resected specimen with sacrificed skin, with proximal end of femoral vessels clamped with mosquito and (b) intraoperative picture showing femoral vessels reconstruction with polytetrafluoroethylene graft (white arrow), and femur (yellow arrow) denuded of its periosteum.

Segment of femoral artery was reconstructed with PTFE graft and it was covered with muscle (Fig. 2). Closure was done after checking distal pulsation.

Post-operative course

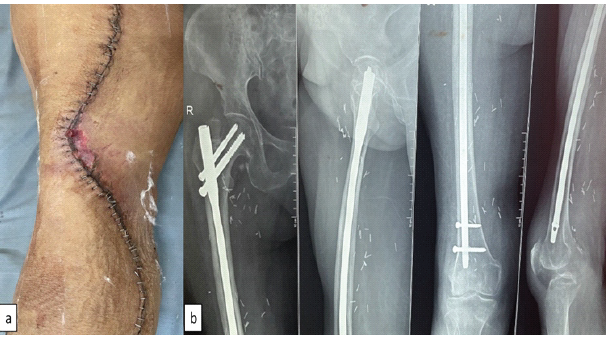

Full weight-bearing walking with walker and knee range of motion exercise was allowed as tolerated. There was small marginal skin necrosis which healed with dressing (Fig. 3). Final histopathology report came out to be liposarcoma with foci of low-grade dedifferentiation (FNCLCC Grade 3) [8] and dimension of tumor was 29 × 24 × 11 cm.

Figure 3: Post-operative image of the wound and radiograph; (a) post-operative image showing superficial skin necrosis managed conservatively and (b) radiograph showing prophylactic nailing at a second stage to prevent radiotherapy-induced fracture.

Prophylactic nailing was done at a second stage after primary wound healed to prevent radiotherapy related fracture [5,6] (Fig. 3). Patient received adjuvant radiotherapy 60 gray in 30 fractions [9] without any complication. Patient was offered chemotherapy [10] but patient refused.

At final follow-up of 35 months, the patient was able to do all her daily routine activity (Fig. 4), her musculoskeletal tumor society (MSTS) score was 24 [11] and she was disease free systemically and locally.

Figure 4: Clinical follow-up; (a) superior view of thigh and knee in full extension; (b) knee flexion up to 100°; and (c) patient is able to walk without support.

MSTS for the lower limb is based on the analysis of six factors, that is, pain, function, emotional acceptance, requirement of support, walking distance, and gait. For each of the six factors, values from 0 to 5 were assigned based on established criteria. The results were expressed as a sum-total with a maximum score of 30 [11].

Surgical resection of STS with adequate margins is an essential part of its treatment [12]. Margins required to decide its adequacy may differ with type of STS, that is, for ALT marginal margin (through reactive zone) is adequate [13] where as for rest of almost all STS wide margin [12] (2 cm or more beyond reactive zone comprising normal tissue) is required. If STS are not resected with adequate margins, it has higher chances of local recurrence which will require more morbid surgery and inferior oncological and functional outcome [12]. Same applies to ALT; moreover, 10% of the ALT dedifferentiates in dedifferentiated liposarcoma [14] which has 15–20% metastatic potential compared to almost nil in ALT. ALT being lipomatous tumor, many times it undergoes inadequate surgery or whoops excision (STS is excised without knowing that it is a sarcoma), leading to multiple recurrences resulting in above-mentioned consequences which may jeopardize patient’s limb or life.

Most of the high-grade STS require radiotherapy as an adjuvant to decrease local recurrence. However, radiotherapy has its long-term side effects, one of the concerning side effects is radiation-induced fracture and these fractures are very difficult to treat [5]. Its chances are high when periosteum is taken as margin specially in an osteoporotic bone. Gortzak et al. [6] has given a simplified nomogram containing variables, that is, age, involved compartment of thigh, tumor size, radiation dose, and periosteal striping; which predicts chances of radiation induced fracture. Putting all variables of this patient in the nomogram predicted very high chances of fracture so prophylactic nailing was done to prevent it.

Rarity of STS makes it vulnerable to inadequate surgery or whoops excision, leading to an eventual worse oncological and functional outcome. It requires decision-making from surgical as well as adjuvant treatment (radiotherapy and chemotherapy) point of view by a multidisciplinary team [15]. Hence, it is better treated at tertiary centers where such team is available to give optimal treatment to the patient.

Usually ALT is considered a lipoma only, so mostly it gets treated at at non-cancer centers. This many time leads to first inadequate surgery leading to high local recurrence rates and chances of it getting converted to higher grade malignancy increases. This results into multiple surgeries leading to significant morbidity to the patient endangering sometimes patient’s limb and life. Hence, it should be treated at tertiary cancer centers at the first instance itself.

References

- 1. Ebrahimpour A, Chehrassan M, Sadighi M, Karimi A, Looha MA, Kafiabadi MJ. Soft tissue sarcoma of extremities: Descriptive epidemiological analysis according to national population-based study. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2022;10:67-77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Katz D, Palmerini E, Pollack SM. More than 50 subtypes of soft tissue sarcoma: Paving the path for histology-driven treatments. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book 2018;38:925-38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Jonczak E, Grossman J, Alessandrino F, Seldon Taswell C, Velez-Torres JM, Trent J, et al. Liposarcoma: A journey into a rare tumor’s epidemiology, diagnosis, pathophysiology, and limitations of current therapies. Cancers (Basel) 2024;16:3858. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Grimer R, Judson I, Peake D, Seddon B. Guidelines for the management of soft tissue sarcomas. Sarcoma 2010;2010:506182. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Sambri A, Gardini L, Dalla Rosa M, Zavatta G, Keskinbora M, Ferrari C, et al. Femoral fracture in primary soft-tissue sarcoma of the thigh treated with radiation therapy: Indications for prophylactic intramedullary nail. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2021;141:1277-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Gortzak Y, Lockwood GA, Mahendra A, Wang Y, Chung PW, Catton CN, et al. Prediction of pathologic fracture risk of the femur after combined modality treatment of soft tissue sarcoma of the thigh. Cancer 2010;116:1553-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kawaguchi N, Matumoto S, Manabe J. New method of evaluating the surgical margin and safety margin for musculoskeletal sarcoma, analysed on the basis of 457 surgical cases. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 1995;121:555-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Gronchi A, Collini P, Miceli R, Valeri B, Renne SL, Dagrada G, et al. Myogenic differentiation and histologic grading are major prognostic determinants in retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:383-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Roeder F. Radiation therapy in adult soft tissue sarcoma-current knowledge and future directions: A review and expert opinion. Cancers (Basel) 2020;12:3242. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ratan R, Patel SR. Chemotherapy for soft tissue sarcoma. Cancer 2016;122:2952-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Enneking WF, Dunham W, Gebhardt MC, Malawar M, Pritchard DJ. A system for the functional evaluation of reconstructive procedures after surgical treatment of tumors of the musculoskeletal system. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;286:241-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Wittenberg S, Paraskevaidis M, Jarosch A, Flörcken A, Brandes F, Striefler J, et al. Surgical margins in soft tissue sarcoma management and corresponding local and systemic recurrence rates: A retrospective study covering 11 years and 169 patients in a single institution. Life (Basel) 2022;12:1694. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Rauh J, Klein A, Baur-Melnyk A, Knösel T, Lindner L, Roeder F, et al. The role of surgical margins in atypical lipomatous tumours of the extremities. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2018;19:152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Papanastassiou ID, Piskopakis A, Gerochristou MA, Chloros GD, Savvidou OD, Issaiades D, et al. Dedifferentiation of an atypical lipomatous tumor of the thigh – a 6 year follow-up study. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact 2019;19:123-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Gómez J, Tsagozis P. Multidisciplinary treatment of soft tissue sarcomas: An update. World J Clin Oncol 2020;11:180-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]