Infection following revision total hip replacement can be a devastating complication. The presence of an exposed prosthesis and associated soft-tissue defect further complicates management. Timely recognition, meticulous and thorough debridement, and early involvement of a plastic surgeon are crucial for achieving a successful outcome.

Dr. Manjesh Reddy S V, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Atal Bihari Vajpayee Institute of Medical Sciences and Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia Hospital, New Delhi - 110001, India. E-mail: svmanjeshreddy@gmail.com

Introduction: Infection following a primary total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a devastating complication. An infected revision THA carries even more significant consequences. This case report describes the successful management of an infected revision THA using debridement, antibiotics, implant retention (DAIR), and a musculocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap coverage in a resource-constrained setting.

Case report: A 37-year-old male patient with hepatitis C presented with a sinus tract at the surgical site following implant removal for an infected THA. He underwent a two-stage revision, utilizing a constrained acetabular cup, due to a lack of identifiable abductor mass observed intraoperatively. Postoperatively, the surgical site dehisced with purulent discharge with exposure of the greater trochanter and trunnion. In consultation with a plastic surgeon, DAIR with musculocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap coverage was done. At 12-month follow-up, the flap remained healthy and well settled, without evidence of infection.

Conclusion: This case highlights the potential of DAIR with flap coverage as a valuable option for managing infected revision THA, particularly in resource-limited settings, considering the associated complications, morbidity, and cost of further revisions.

Keywords: Hip arthroplasty, revision, debridement, implant retention, flap cover.

Infection following revision total hip arthroplasty (THA) is a serious complication that presents a significant challenge to operating surgeons. Reported infection rates after revision arthroplasty range from approximately 5% for aseptic cases to as high as 20% for septic revisions [1,2]. Several factors contribute to the complexity of managing these infections, including patient comorbidities, altered anatomy, bone loss, extended operative time, and increased blood loss. Two primary management strategies exist for infected revision THA: Debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR) and two-stage revision arthroplasty. The choice between these strategies typically depends on the timing of infection onset and patient-specific factors. While the literature on DAIR for infected revision cases is limited, this report presents a case of a successful DAIR procedure combined with flap coverage to salvage an infected revision THA with significant soft-tissue compromise.

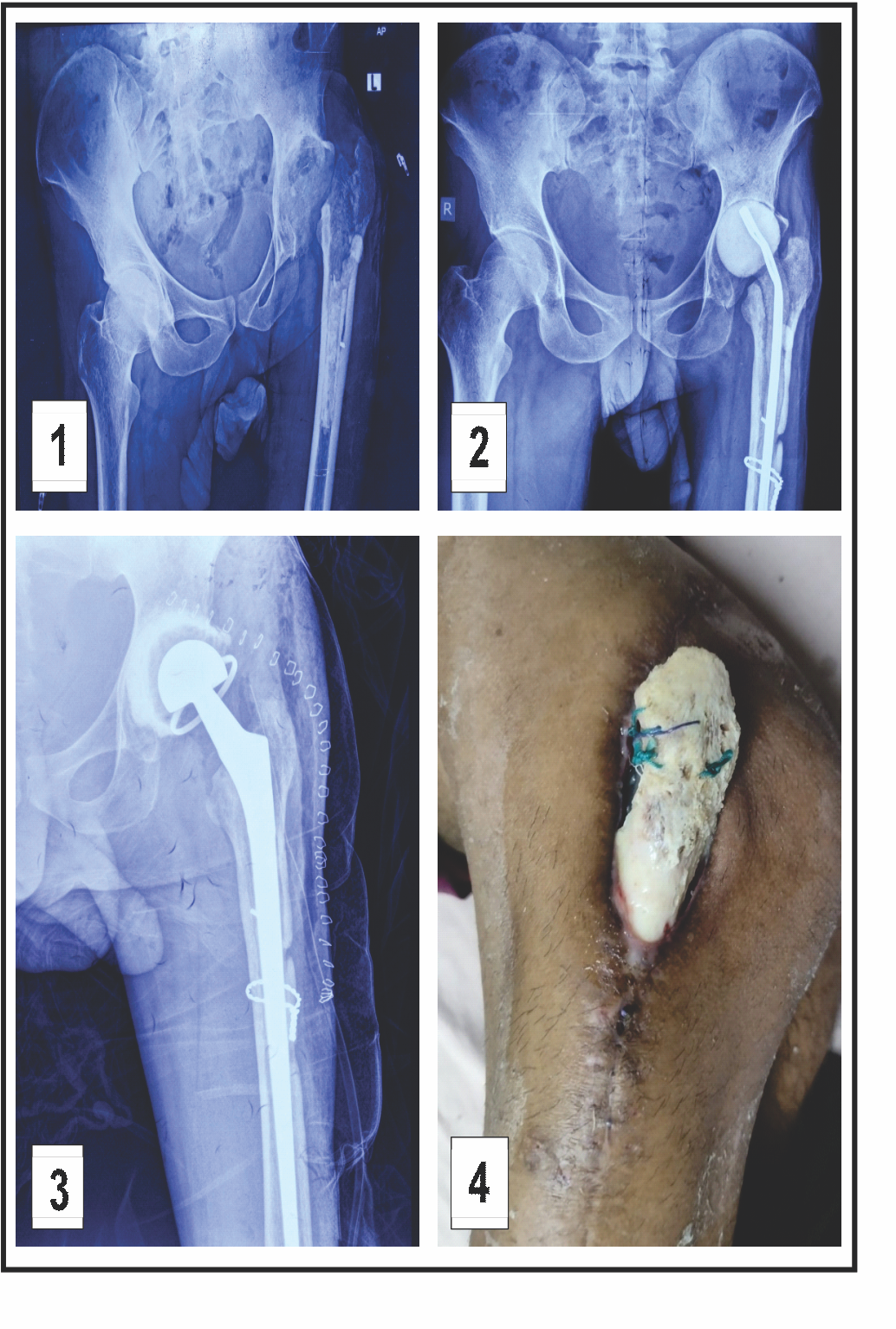

A 37-year-old male patient with hepatitis C presented with a persistent sinus tract at the surgical site following implant removal for an infected THA. The patient had undergone total hip replacement 4 years ago, which subsequently got infected. Implant removal was done 1 year back. Radiographs showing the left hip status after implant removal are shown in Fig. 1. At presentation, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and total leukocyte count were 56 mg/L, 78 mm/h, and 14,700 cells/mm3, respectively. A two-stage revision was planned, and the risks and benefits were discussed with the patient.

Stage 1 involved surgical site debridement, antibiotic spacer placement, and initiation of intravenous antibiotics. Culture report revealed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, sensitive to vancomycin, which was continued for 6 weeks. Fig. 2 displays hip radiographs with the antibiotic spacer in situ. Two weeks after completing antibiotic treatment, CRP levels normalized.

Stage 1 involved surgical site debridement, antibiotic spacer placement, and initiation of intravenous antibiotics. Culture report revealed methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, sensitive to vancomycin, which was continued for 6 weeks. Fig. 2 displays hip radiographs with the antibiotic spacer in situ. Two weeks after completing antibiotic treatment, CRP levels normalized.

Stage 2 included removal of the antibiotic spacer and implantation of a new prosthesis (Fig. 3). Due to the absence of identifiable abductor musculature intraoperatively, a constrained acetabular cup was utilized. The 1st post-operative week was uneventful. However, by the end of the 2nd post-operative week, the surgical site dehisced with purulent discharge. Subsequently, the entire greater trochanter became exposed and devitalized, with concurrent exposure of the trunnion (Fig. 4). In consultation with a plastic surgeon, the decision was made to proceed with DAIR and flap coverage. All devitalized bone was debrided until healthy bleeding points were observed (Fig. 5). Simultaneously, a musculocutaneous anterolateral thigh flap was raised and inset by the plastic surgery team (Fig. 6). Multiple drains were placed. Postoperatively, the patient received intravenous piperacillin-tazobactam and linezolid for 6 weeks. Culture of intraoperative samples was negative. Sutures were removed on post-operative day 14. The patient was advised to remain on non-weight-bearing mobilization from post-operative day 2. Hip range-of-motion exercises and partial weight-bearing ambulation were initiated during the 3rd post-operative week, progressing to full weight-bearing by the 6th week. At the 3-month follow-up, the flap had healed successfully (Fig. 7). Inflammatory markers at that time were CRP 4.1 mg/L and ESR 28 mm/h. Post-operative radiographs were obtained at 6 weeks, 6 months, and 12 months (Fig. 8). At the most recent follow-up (12 months), the patient was ambulant with walker support and doing well clinically.

Infection is a leading cause of failure in revision THA, with prior infection being the most significant risk factor for recurrence. Most re-revisions require a two-stage procedure, which is considered the standard treatment for infections presenting more than 4 weeks after the index surgery [3]. Stage 1 involves implant removal, antibiotic spacer placement, and targeted intravenous antibiotics therapy. Stage 2, following confirmation of normalized CRP, consists of spacer removal and implantation of the new revision prosthesis. This staged approach is preferred in delayed presentations, as the biofilm has typically matured, making eradication without implant removal challenging. Conversely, for infections presenting within 4 weeks of the index procedure, DAIR may be a viable option. At this stage, the biofilm may not have matured, increasing the chances of successful infection eradication through thorough debridement without the need for implant removal. Several factors influence the success of DAIR, including comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus, liver disease, chronic renal failure, systemic inflammatory disorders (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus), glucocorticoid use, smoking, and the local soft-tissue status. Optimal outcomes are anticipated in patients without these risk factors. The high cost of implants in resource-limited setting can also considerably influence management decisions. Reported success rates for DAIR in the literature vary widely, ranging from 30 to 95%, with an overall success rate of approximately 61% [4,5]. Successful outcomes depend heavily on thorough and meticulous debridement [6]. A strong correlation exists between the time from symptom onset to intervention and the success of DIAR, with shorter intervals (ideally within 7 days) associated with better outcomes [7,6]. However, the time elapsed from the index surgery to DAIR does not significantly affect re-revision rates at 1 year [8]. Exchanging the femoral head and acetabular liner also improves the likelihood of success [6,9]. Additionally, procedures performed by experienced surgeons yield higher success rates compared to those done by less experienced surgeons [5]. If successful, DAIR does not compromise long-term implant survival [10]. Studies have shown DAIR to be a valid treatment option for acute infection after revision total knee replacement [11]. In this case, the patient was a young, thin-built adult male with a history of chronic smoking, hepatitis C infection, and impaired liver function. These factors, particularly Hepatitis C and smoking, likely contributed to compromised surgical site healing. Moreover, the soft-tissue over the greater trochanter was severely deficient. Intraoperatively, the absence of identifiable abductor musculature necessitated the use of a constrained acetabular cup. Postoperatively, wound dehiscence led to greater trochanter exposure and devitalization. Studies have shown that when wound dehiscence involves the fascial layer, implant exposure is likely, and flap coverage is often required [12,13]. Given the extensive soft-tissue defect (10 × 5 cm) and the patient’s comorbidities, primary closure and healing were deemed unlikely. In consultation with a plastic surgeon, the decision was made to perform surgical debridement and flap cover. Although evidence supporting the use of DAIR combined with flap coverage in revision THA is limited, this case demonstrates that immediate flap coverage after debridement may promote healing by improving local vascularity, supporting immune cell delivery, facilitating antibiotic penetration, and promoting tissue regeneration [14,15,16]. The placement of multiple drains is also important to prevent fluid accumulation in dead space [17]. Early flap coverage has been associated with better outcomes and is recommended in cases of persistent prosthetic infection [16]. Flaps can conform to irregular-shaped wounds, fill dead space, and reduce the risk of hematoma formation [18,19]. Gluteus maximus, rectus abdominis, and vastus lateralis flaps are commonly used to cover defects in the hip region [20]. Among these, the vastus lateralis flap often preferred due to ease of harvest, reliable blood supply, and sufficient bulk to fill dead space [20]. Similarly, an 80% success rate has been reported for the gastrocnemius flap in managing exposed knee prosthesis [21]. Gusenoff et al.’s algorithm for complex wound management demonstrated 100% prosthesis salvage when early plastic surgery consultation was obtained [15]. In our patient, the flap healed successfully without complications and was well-integrated by the 3-month follow-up. Literature on DAIR for infected revision THA remains limited. A study by Chang et al. reported on 10 cases of delayed or late infections following revision THA managed with DAIR [2]. These patients underwent debridement, liner and femoral head exchange, and received post-operative culture-specific antibiotic therapy. The study reported an 80% success rate at 2-year follow-up with no mortalities. However, this study did not address the management strategies for acute infections in revision THA. At 1-year follow-up, our patient was ambulant with walker support and had no signs of reinfection. Further prospective studies with larger cohorts and longer follow-up are needed to validate the efficacy of DAIR combined with flap coverage in similar complex scenarios.

DAIR remains a valuable treatment option for acute infection in revision THA, particularly in resource-constrained settings. Contrary to routine practice, extensive debridement with immediate flap coverage may enhance local biology and promote tissue healing at the recipient site.

Patients undergoing revision arthroplasty for infected arthroplasty are at significantly higher risk of infection compared to primary cases. The timing of symptom onset is critical. Infection should be recognized as early as possible, especially in the immediate post-operative weeks. Thorough surgical debridement should be performed as soon as possible after symptom onset. If extensive debridement is required, the implant is exposed, or wound dehiscence involves the fascial layer, concurrent flap coverage should be considered in consultation with a plastic surgeon.

References

- 1. Jafari SM, Coyle C, Mortazavi SM, Sharkey PF, Parvizi J. Revision hip arthroplasty: Infection is the most common cause of failure. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2046-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Chang JD, Kim IS, Lee SS, Yoo JH. Acute delayed or late infection of revision total hip arthroplasty treated with debridement/antibiotic-loaded cement beads and retention of the prosthesis. Hip Pelvis 2017;29:35-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Engesæter LB, Dale H, Schrama JC, Hallan G, Lie SA. Surgical procedures in the treatment of 784 infected THAs reported to the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop 2011;82:530-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Slullitel PA, Onativia JI, Buttaro MA, Sanchez ML, Comba F, Zanotti G, et al. State-of-the-art diagnosis and treatment of acute peri-prosthetic joint infection following primary total hip arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2018;3:434-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Martin R, Fishley W, Kingman A, Carluke I, Kramer D, Partington P, et al. WHO dairs wins? Orthop Proc 2024;106-B:43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Deckey DG, Christopher ZK, Bingham JS, Spangehl MJ. Principles of mechanical and chemical debridement with implant retention. Arthroplasty 2023;5:16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Rahardja R, Zhu M, Davis JS, Manning L, Metcalf S, Young SW. Success of debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention in prosthetic joint infection following primary total knee arthroplasty: Results from a prospective multicenter study of 189 cases. J Arthroplasty 2023;38:S399-404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Van der Ende B, van Oldenrijk J, Reijman M, Croughs PD, van Steenbergen LN, Verhaar JA, et al. Timing of debridement, antibiotics, and implant retention (DAIR) for early post-surgical hip and knee prosthetic joint infection (PJI) does not affect 1-year re-revision rates: Data from the Dutch Arthroplasty Register. J Bone Jt Infect 2021;6:329-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Awad F, Boktor J, Joseph V, Lewis MH, Silva C, Sarasin S, et al. Debridement, antibiotics and implant retention (DAIR) following hip and knee arthroplasty: Results and findings of a multidisciplinary approach from a non-specialist prosthetic infection centre. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2024;106:633-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Clauss M, Hunkeler C, Manzoni I, Sendi P. Debridement, antibiotics and implant retention for hip periprosthetic joint infection: Analysis of implant survival after cure of infection. J Bone Jt Infect 2020;5:35-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Hulleman CW, de Windt TS, Veerman K, Goosen JH, Wagenaar FB, van Hellemondt GG. Debridement, antibiotics and implant retention: A systematic review of strategies for treatment of early infections after revision total knee arthroplasty. J Clin Med 2023;12:5026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Amin NH, Speirs JN, Simmons MJ, Lermen OZ, Cushner FD, Scuderi GR. Total knee arthroplasty wound complication treatment algorithm: Current soft tissue coverage options. J Arthroplasty 2019;34:735-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. .Economides JM, DeFazio MV, Golshani K, Cinque M, Anghel EL, Attinger CE, et al. Systematic review and comparative meta-analysis of outcomes following pedicled muscle versus fasciocutaneous flap coverage for complex periprosthetic wounds in patients with total knee arthroplasty. Arch Plast Surg 2017;44:124-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Lesavoy MA, Dubrow TJ, Wackym PA, Eckardt JJ. Muscle-flap coverage of exposed endoprostheses. Plast Reconstr Surg 1989;83:90-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Gusenoff JA, Hungerford DS, Orlando JC, Nahabedian MY. Outcome and management of infected wounds after total hip arthroplasty. Ann Plast Surg 2002;49:587-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Rovere G, Smakaj A, Calori S, Barbaliscia M, Ziranu A, Pataia E, et al. Use of muscular flaps for the treatment of knee prosthetic joint infection: A systematic review. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2022;14:33943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Warren SI, Murtaugh TS, Lakra A, Reda LA, Shah RP, Geller GA, et al. Treatment of periprosthetic knee infection with concurrent rotational muscle flap coverage is associated with high failure rates. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:3263-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Marais LC, Hungerer S, Eckardt H, Zalavras C, Obremskey WT, Ramsden A, et al. Key aspects of soft tissue management in fracture-related infection: recommendations from an international expert group. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2024;144:259-68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Rovere G, De Mauro D, D’Orio M, Fulchignoni C, Matrangolo MR, Perisano C, et al. Use of muscular flaps for the treatment of hip prosthetic joint infection: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:1059. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Suda AJ, Heppert V. Vastus lateralis muscle flap for infected hips after resection arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2010;92:1654-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Gerwin M, Rothaus KO, Windsor RE, Brause BD, Insall JN. Gastrocnemius muscle flap coverage of exposed or infected knee prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1993;286:64-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]