Prompt multidisciplinary management and prolonged antifungal therapy can achieve infection control even in complex Candida periprosthetic hip infections with recurrent dislocations.

Dr. Angelos Kontos, Department of Orthopaedics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens, KAT Hospital, Athens, Greece. E-mail: aggelos_knt@hotmail.com

Introduction: Fungal periprosthetic joint infections (PJI) are exceptionally rare, accounting for <1% of all PJIs. Among them, Candida albicans is the most frequently implicated pathogen, yet its management remains highly challenging.

Case Report: We report the case of an 85-year-old female who presented with a draining sinus at the right hip, 4 weeks after revision total hip arthroplasty (THA). Her surgical history included a prior failed revision due to recurrent dislocation. Clinical and laboratory findings suggested PJI. Intraoperative cultures and sonication confirmed multimicrobial and C. albicans infection. Following 4 months of antimicrobial therapy, she underwent debridement and removal of the acetabular component. Postoperatively, she received a 4-week course of trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (960 mg 3 times daily) and a 12-week course of fluconazole (200 mg twice daily). The post-operative course was uneventful. At 6 and 12-month follow-up, she remained asymptomatic with a well-healed wound and negative inflammatory markers.

Conclusion: Early recognition and combined surgical–pharmacological management can lead to infection eradication and functional preservation, even in rare polymicrobial fungal PJIs.

Keywords: Candida albicans, fungal periprosthetic joint infection, total hip arthroplasty, debridement and implant retention, fluconazole.

Periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) is one of the most devastating complications following total hip arthroplasty (THA), occurring in 1–2% of primary and up to 4% of revision procedures [1,2]. While bacterial pathogens predominate, fungal PJIs (fPJI) are exceedingly rare, accounting for <1% of all cases, with Candida species being the most frequently isolated organisms [3,4]. Their management is particularly challenging due to diagnostic delays, limited evidence-based guidelines, and high rates of treatment failure. We herein report a rare case of Candida albicans PJI in an elderly patient following multiple revision THAs, highlighting the diagnostic and therapeutic complexities associated with this entity.

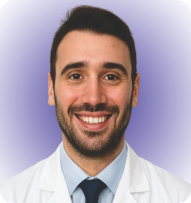

An 85-year-old female patient underwent a primary THA in 1999. In 2021, she required her first revision THA operation, due to mechanical loosening of the implant without any signs of infection after laboratory and clinical evaluation. Three weeks after the revision, the patient sustained a prosthetic hip dislocation, which was treated with open reduction. Due to persistent instability, a second revision THA was performed 3 weeks later. All of the aforementioned interventions were performed at another institution. Four weeks after this latest revision, the patient presented to our outpatient department with a draining sinus located near the surgical incision of the right hip. Following multidisciplinary team discussion, she was admitted to our hospital for further evaluation (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Revision total hip arthroplasty with a sinus tract infection upon presentation.

On admission, laboratory investigations demonstrated elevated inflammatory markers, with a C-reactive protein (CRP) level of 4.46 mg/dL (reference value <0.5 mg/dL) and an erythrocyte sedimentation rate level of 96 mm/h (reference range 1–20 mm/h). Using the old incision and utilizing a posterior hip approach, the patient underwent her first surgical debridement, during which cerclage wires were removed and sent for sonication, and both soft tissue and bone specimens were obtained for microbiological culture. Empirical intravenous antibiotic therapy was initiated postoperatively with daptomycin (10 mg/kg/day) and cefepime (2 g 3 times daily). Microbiological analysis revealed both bacterial and fungal pathogens. Bone cultures yielded Staphylococcus simulans (2/3), C. albicans (3/3), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (1/3). Tissue specimens grew S. simulans (5/7), C. albicans (3/7), and Staphylococcus epidermidis (2/7). Sonication of the cerclage wires demonstrated S. simulans. Based on the antimicrobial susceptibility profile, antibiotic therapy was subsequently modified to intravenous cloxacillin (2 g 6 times daily) combined with intravenous fluconazole (200 mg twice daily). Serial monitoring of inflammatory markers was performed, and the patient remained hemodynamically stable and afebrile until the 18th post-operative day, with inflammatory markers remaining at low values. On the 18th post-operative day, wound drainage became more pronounced. From post-operative day 18 to 25, the patient was closely monitored, experiencing intermittent low-grade fever up to 37.4°C and requiring frequent wound inspections and dressing changes due to persistent drainage. On the 25th post-operative day, the patient developed a fever up to 38.7°C, with a sharp rise in CRP to 14 mg/dL. Blood and urine cultures were obtained, whereas chest radiography and rapid testing for COVID-19 and influenza were unremarkable. On the 27th post-operative day, CRP had further increased to 18.4 mg/dL, and blood cultures yielded Escherichia coli. At that point, intravenous meropenem (2 g 3 times daily) was added to the antimicrobial regimen.

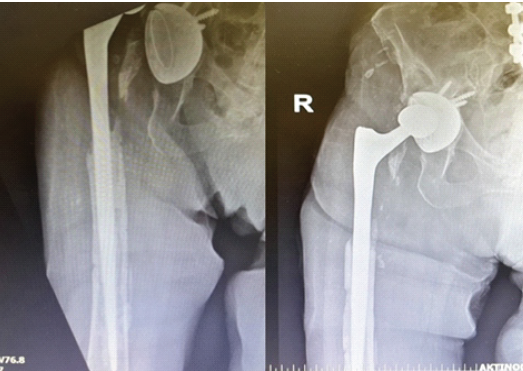

On the 30th post-operative day, the patient underwent a second surgical debridement through the previous incision and approach, which included removal of the remaining cerclage wires and retrieval of bone cement specimens for sonication. Following infectious disease consultation, the antimicrobial regimen was adjusted to meropenem, caspofungin (70 mg/day intravenously), and daptomycin (700 mg/day intravenously), pending the results of the repeat microbiological cultures. The subsequent post-operative course was uneventful. Sonication of the retrieved cement yielded C. albicans. Meropenem was administered for a total of 3 weeks for the treatment of bacteremia, whereas caspofungin and daptomycin were continued intravenously. At 3 weeks postoperatively, the wound had healed adequately, sutures were removed, and the patient was discharged in good general condition. She was prescribed oral trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (960 mg twice daily) and fluconazole (200 mg twice daily) for prolonged suppressive therapy. Twenty days after discharge, the patient was readmitted due to a new prosthetic hip dislocation, which was managed with closed reduction in the emergency department. On readmission, her CRP was 1.06 mg/dL, without clinical or laboratory evidence of recurrent infection. Given the absence of systemic inflammatory response, a conservative approach was adopted, and she was discharged after a short hospital stay with instructions to continue oral fluconazole and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Anteroposterior radiograph demonstrating dislocation of a revision total hip arthroplasty, treated with closed reduction during ongoing antibiotic and antifungal therapy.

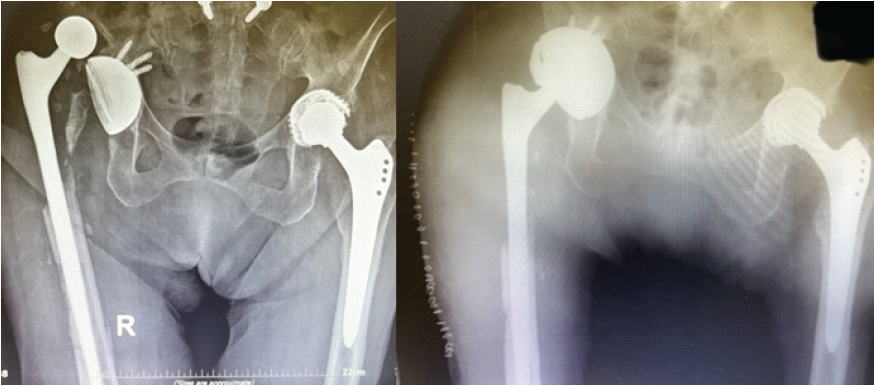

Six weeks after discharge, the patient sustained another prosthetic hip dislocation. She was admitted again, 4 months after the initial debridement, while still receiving oral fluconazole and trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole. On readmission, pre-operative CRP was 2.68 mg/dL. A surgical intervention was decided upon. Similarly, a posterior hip approach was utilized. Intraoperatively, the acetabular component, ceramic head, bone cement, and screws were removed. A tantalum acetabular cup was implanted with five screws, coupled with a constrained polyethylene liner. The femoral stem was deemed stable intraoperatively and was therefore retained (Fig. 3). The ceramic head was replaced. The removed acetabular component was sent for sonication, and two drains were placed, which were retained for 7 days.

Figure 3: Hip dislocation in the setting of fungal periprosthetic joint infection, treated with acetabular cup revision.

Infectious disease specialists recommended oral trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (960 mg 3 times daily) for 4 weeks and oral fluconazole (200 mg twice daily) for 12 weeks. Immediately postoperatively, the patient remained hemodynamically stable and afebrile, requiring transfusion of one unit of packed red blood cells. Sonication of the retrieved acetabular component showed no microbial growth. On the 11th post-operative day, CRP had decreased to 4.61 mg/dL, and the wound appeared clean, without clinical signs of infection. The patient was discharged in good general condition.

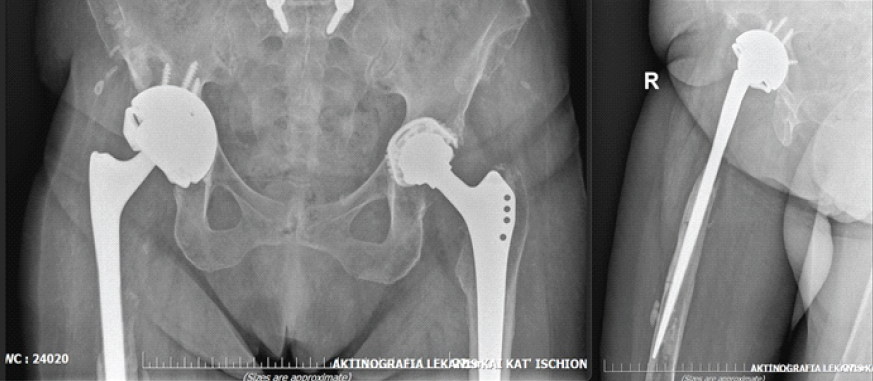

The patient successfully completed the prescribed antimicrobial regimen. At both 6- and 12-month follow-up evaluations, she was seen at the outpatient clinic, where she demonstrated a well-healed surgical wound with no clinical or laboratory evidence of infection. At the latest follow-up, the patient was ambulatory with the aid of a cane and able to perform activities of daily living independently. She reported minimal discomfort in the right hip. Functional assessment using the Harris Hip Score yielded a value of 86, indicating good overall function. Despite the radiographic evidence of proximal femoral bone loss, the patient remained asymptomatic, reporting no pain or functional limitation. Given the absence of clinical symptoms, a conservative approach with close follow-up was elected. Should progressive pain or mechanical compromise develop in the future, reconstruction with a proximal femoral replacement (tumor-type prosthesis) would represent an appropriate surgical option (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Pelvis anteroposterior (left) and right hip lateral (right) view at 12 months follow-up.

fPJI is an uncommon but devastating complication following total joint arthroplasty. C. albicans is the most frequently isolated pathogen, though bacterial–fungal coinfections, as in our patient, are increasingly recognized and associated with particularly poor outcomes [5]. Reported incidence of fPJI is <1% of all PJIs, yet mortality and treatment failure rates remain disproportionately high compared with bacterial infections [6,7]. The prevailing consensus in the literature is that implant removal—most reliably through a two-stage exchange—offers the highest probability of infection eradication in fungal cases [8]. Two-stage revision achieves infection-free survival in approximately 80–90% of patients, whereas debridement and implant retention (DAIR) is generally discouraged. Nevertheless, our case demonstrates that, under selected circumstances, a repeated DAIR as a first-phase approach followed by a two-stage revision as a second-phase strategy can lead to long-term remission, even in the context of a documented fungal infection. Several aspects render this case distinctive. First and foremost, it involved a true polymicrobial infection with C. albicans and coagulase-negative staphylococci, later complicated by E. coli bacteremia. Polymicrobial fPJIs are consistently reported to have worse outcomes than monomicrobial infections [5]. In addition, our strategy combined two consecutive surgical debridements with targeted removal of cerclage wires and cement, followed by partial component revision (replacement of the acetabular component and head while retaining a stable femoral stem). This hybrid approach, situated between DAIR and full two-stage revision, is rarely described in fPJI but proved effective here. Finally, the antifungal regimen was escalated appropriately from fluconazole to caspofungin during the acute phase, followed by prolonged oral fluconazole suppression, in accordance with emerging evidence regarding biofilm-active therapy [9]. The role of sonication was also instructive. In our case, sonication repeatedly demonstrated fungal growth, confirming the diagnosis and guiding escalation of therapy, before ultimately turning negative after partial revision. Although sonication is more sensitive than tissue culture alone, its diagnostic yield in PJI remains imperfect, and negative results cannot definitively exclude infection [10,11]. Here, positive sonication provided strong microbiological evidence supporting aggressive combined surgical and pharmacological management. Antifungal therapy in fPJI remains a matter of debate. While fluconazole has historically been the most frequently used agent, its efficacy against mature biofilm is limited. In vitro and translational studies demonstrate that echinocandins and amphotericin B have superior antibiofilm activity [12,13]. In line with this, our patient received caspofungin in combination with broad-spectrum antibacterials after recurrent drainage and systemic bacteremia, followed by fluconazole as consolidation therapy once clinical stability was achieved. The favorable outcome underscores the importance of tailoring therapy dynamically, balancing toxicity, biofilm activity, and oral feasibility for long-term suppression.

At 1 year of follow-up, the patient remained clinically well, with no signs of recurrent infection, despite the presence of retained femoral hardware. This highlights that, although complete hardware removal remains the gold standard in chronic fPJI, individualized strategies can succeed when combined with meticulous debridement, multidisciplinary management, and prolonged antifungal therapy. Such outcomes, though rare, provide real-world evidence that DAIR and partial revision may be viable alternatives in select patients – particularly elderly individuals in whom full two-stage revision may carry prohibitive morbidity.

Polymicrobial fPJI of the hip can be controlled through a tailored combination of surgical debridement, partial component revision, and prolonged antifungal therapy. Positive sonication findings were critical for guiding management, and long-term infection-free survival was achieved despite implant retention. While two-stage revision remains the reference standard, this report demonstrates that repeated DAIR-based strategies may, in select scenarios, offer a limb- and function-preserving alternative.

Individualized surgical strategy and prolonged antifungal therapy may lead to remission in complex Candida periprosthetic hip infections, avoiding extensive two-stage revisions in selected elderly patients.

References

- 1. Osmon DR, Berbari EF, Berendt AR, Lew D, Zimmerli W, Steckelberg JM, et al. Diagnosis and management of prosthetic joint infection: Clinical practice guidelines by the infectious diseases society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2013;56:e1-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kunutsor SK, Whitehouse MR, Blom AW, Beswick AD, INFORM Team. Re-infection outcomes following one- and two-stage surgical revision of infected hip prosthesis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2015;10:e0139166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Guan Y, Zheng H, Zeng Z, Tu Y. Surgical procedures for the treatment of fungal periprosthetic infection following hip arthroplasty: A systematic scoping review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2024;86:2786-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Sambri A, Zunarelli R, Fiore M, Bortoli M, Paolucci A, Filippini M, et al. Epidemiology of fungal periprosthetic joint infection: A systematic review of the literature. Microorganisms 2022;11:84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Shang G, Zhao S, Yang S, Li J. The heavy burden and treatment challenges of fungal periprosthetic joint infection: A systematic review of 489 joints. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024;25:648. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Gonzalez MR, Bedi AD, Karczewski D, Lozano-Calderon SA. Treatment and outcomes of fungal prosthetic joint infections: A systematic review of 225 cases. J Arthroplasty 2023;38:2464-71 e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Gibert C, Marchetti C, Guery B, Steinmetz S, Ferry T, Lamoth F. Outcome predictors of Candida prosthetic joint infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis 2025;12:ofaf281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Kuiper JW, Van Den Bekerom MP, Van Der Stappen J, Nolte PA, Colen S. 2-stage revision recommended for treatment of fungal hip and knee prosthetic joint infections. Acta Orthop 2013;84:517-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Ferreira JA, Carr JH, Starling CE, De Resende MA, Donlan RM. Biofilm formation and effect of caspofungin on biofilm structure of Candida species bloodstream isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009;53:4377-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ribeiro TC, Honda EK, Daniachi D, Cury RP, Da Silva CB, Klautau GB, et al. The impact of sonication cultures when the diagnosis of prosthetic joint infection is inconclusive. PLoS One 2021;16:e0252322. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Trampuz A, Piper KE, Jacobson MJ, Hanssen AD, Unni KK, Osmon DR, et al. Sonication of removed hip and knee prostheses for diagnosis of infection. N Engl J Med 2007;357:654-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Dinh A, McNally M, D’Anglejan E, Mamona Kilu C, Lourtet J, Ho R, et al. Prosthetic joint infections due to candida species: A multicenter international study. Clin Infect Dis 2025;80:347-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Escola-Verge L, Rodríguez-Pardo D, Corona PS, Pigrau C. Candida periprosthetic joint infection: Is it curable? Antibiotics (Basel) 2021;10:458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]