Open meniscus repair was associated with significantly lower risks of re-tear and revision compared with arthroscopic repair, indicating superior long-term durability. However, open repair carried a modestly higher risk of osteoarthritis (OA) progression and venous thromboembolism. These findings highlight the importance of balancing durability against complication risk when selecting surgical techniques for meniscal repair.

Dr. Ismail Pandor, Department of Orthopedics, Krishna Vishwa Vidhyapeeth, Karad, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: i.pandor07@gmail.com

Introduction: Meniscal tears are among the most frequent knee injuries requiring surgical intervention. Arthroscopic repair has largely supplanted open repair due to its minimally invasive nature, yet long-term comparative outcomes remain poorly characterized. This study compared clinical outcomes of arthroscopic versus open meniscus repair using a large multicenter electronic health record database.

Methods: We performed a retrospective cohort analysis using the TriNetX US Collaborative Network, including adult patients (18–60 years) who underwent meniscus repair between 2010 and 2025. Cohorts were defined by surgical approach: Open repair (CPT 27427–27429) and arthroscopic repair (CPT 29882–29883). Outcomes assessed within two years post-surgery were meniscal repair failure/re-tear, revision meniscus surgery, knee osteoarthritis (OA) progression, and venous thromboembolism (VTE). Propensity score matching (1:1) balanced demographics and comorbidities, yielding 17,925 patients per group. Risk ratios (RR), hazard ratios (HR), and Kaplan–Meier analyses were calculated.

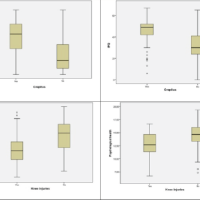

Results: Before matching, the arthroscopic cohort (n = 48,101) was older and more frequently male compared with the open cohort (n = 17,966). After matching (n = 17,925 each), groups were well balanced across demographics and comorbidities. Median follow-up was 22 months in both groups. Meniscal failure was significantly higher after arthroscopic repair (51.4%) than open repair (16.2%) (RR 0.32, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.30–0.33; HR 0.24, 95% CI 0.23–0.25; P < 0.001). Revision surgery occurred in 3.4% of arthroscopic versus 1.0% of open repairs (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.25–0.35; HR 0.29, 95% CI 0.25–0.35; P < 0.001). Conversely, OA progression was slightly more frequent in open repair patients (6.1% vs. 4.9%; RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.12–1.34; HR 1.23, 95% CI 1.12–1.34; log-rank P < 0.001). VTE incidence was low overall but higher after open repair (1.9% vs. 1.4%; RR 1.42, 95% CI 1.20–1.67; HR 1.41, 95% CI 1.20–1.66; P < 0.001).

Conclusions: In this large matched cohort, open meniscus repair was associated with markedly lower risks of meniscal failure and revision surgery compared with arthroscopic repair. However, open repair carried modestly higher risks of knee OA progression and VTE. These findings suggest open repair offers superior meniscal durability but at the expense of slightly increased long-term joint degeneration and thromboembolic risk. Shared decision-making should incorporate both durability and complication profiles, and prospective studies with longer follow-up are warranted.

Keywords: Meniscus repair, arthroscopic surgery, open repair, knee osteoarthritis, venous thromboembolism

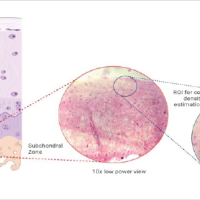

Meniscal tears are among the most common intra-articular knee injuries, particularly in young active populations, and the meniscus is crucial for load transmission, shock absorption, joint stability, and prevention of cartilage degeneration [1]. Loss of meniscus integrity increases contact pressures and accelerates articular cartilage wear, contributing to osteoarthritis (OA) onset [2]. Given these biomechanics, meniscal repair, rather than removal, is increasingly preferred to preserve native tissue and delay joint degeneration [3]. Historically, open surgical repair was the standard technique, but advances in instrumentation and surgical technique have shifted practice toward arthroscopic repair, which is less invasive, offers faster rehabilitation, and avoids large incisions [4]. Arthroscopic techniques include inside-out, outside-in, and all-inside repair strategies, each with different trade-offs in suture strength, ease of use, and risk of neurovascular injury [5]. Nevertheless, open repair retains biomechanical advantages: Direct access and stable fixation under direct vision. Some early comparative studies of open versus arthroscopic repair reported similar healing rates and low complication rates for both techniques, especially in stable knees [6].

Yet, long-term outcomes remain uncertain. Meta-analyses of arthroscopic repair suggest pooled failure rates between 15% and 25% at mid- to long-term follow-up [7,8]. A systematic review of contemporary clinical series found that successful meniscal repair is associated with slower progression of knee OA compared to meniscectomy [9]. However, many comparative trials suffer from small sample sizes, heterogeneous tear types, and limited follow-up durations, with few modern studies directly comparing open versus arthroscopic approaches [10]. Furthermore, the effect of repair modality on revision surgery, re-tear rates, OA progression, and complications (e.g., thromboembolism) remains insufficiently characterized in large cohorts.

In this study, we leverage a large federated electronic health record (EHR) database (TriNetX) to compare outcomes of arthroscopic versus open meniscal repair in a matched adult population. We hypothesized that open repair would lead to lower re-tear and revision rates, while arthroscopic repair would have fewer procedure-related complications.

Study design and data source

This retrospective cohort study used TriNetX Live, a federated health research network of EHRs. All data were de-identified, exempting the need for IRB approval. TriNetX automatically applied inclusion and exclusion criteria, performed propensity score matching (PSM), and calculated outcome measures. Analyses were performed on the platform version current as of September 24, 2025.

Participants and cohort definitions

Eligible patients were adults aged 18–60 who underwent meniscus repair between January 1, 2010, and January 6, 2025. Two cohorts were defined:

Open Meniscus Repair: 17,966 patients met criteria before matching.

Arthroscopic Meniscus Repair: 48,101 patients met criteria before matching.

The index date was the first eligible repair. No prior meniscus repairs were permitted in the previous 20 years. Patients were assigned exclusively to one cohort.

Outcomes and follow-up: Variables and measurements

Four outcomes were assessed within 2 years:

Meniscal repair failure/reinjury: Recurrent or residual meniscal tear in the index knee

Revision meniscus surgery: Any subsequent meniscal procedure

Knee OA progression: New or worsening knee OA

Venous thromboembolism (VTE): Any deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism post-surgery

Events before follow-up were excluded from the study. Outcomes were tracked from 1 day to 2 years post-surgery. Time-to-event analyses censored patients at the last available data or 730 days. Pre-matching median follow-up was 21.5 months for both cohorts. After PSM, median follow-up remained comparable (653 days open vs. 651 days arthroscopic).

PSM

PSM was conducted using logistic regression, including demographics (age, sex, race, and ethnicity) and clinical covariates (body mass index (BMI), diabetes, hypertension, smoking, alcohol use, and prior knee conditions). Matching was 1:1 nearest-neighbor without replacement, with a caliper of 0.1 SD of the logit. 17,925 patients were retained per cohort, excluding only 41 open cases (<0.3%). Post-matching balance was excellent, with standardized differences <0.1 for all covariates. Example: post-match mean age 29.8 years in both groups, and male sex proportion 49.0% versus 48.6%.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed within TriNetX. Continuous variables were compared with t-tests, categorical with Chi-square tests, significance threshold P < 0.05.

Outcome analyses

Risk analysis: Two-year cumulative incidence, risk ratios (RR), risk differences with 95% confidence interval (CI), and P-values via z-tests.

Time-to-event: Kaplan–Meier survival analysis with log-rank tests and Cox proportional hazards models to estimate hazard ratios (HR). PH assumption was tested via Schoenfeld residuals; no violations detected.

Both RR and HR with 95% CI and P-values are reported. All analyses followed STROBE guidelines and were formatted per Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research standards.

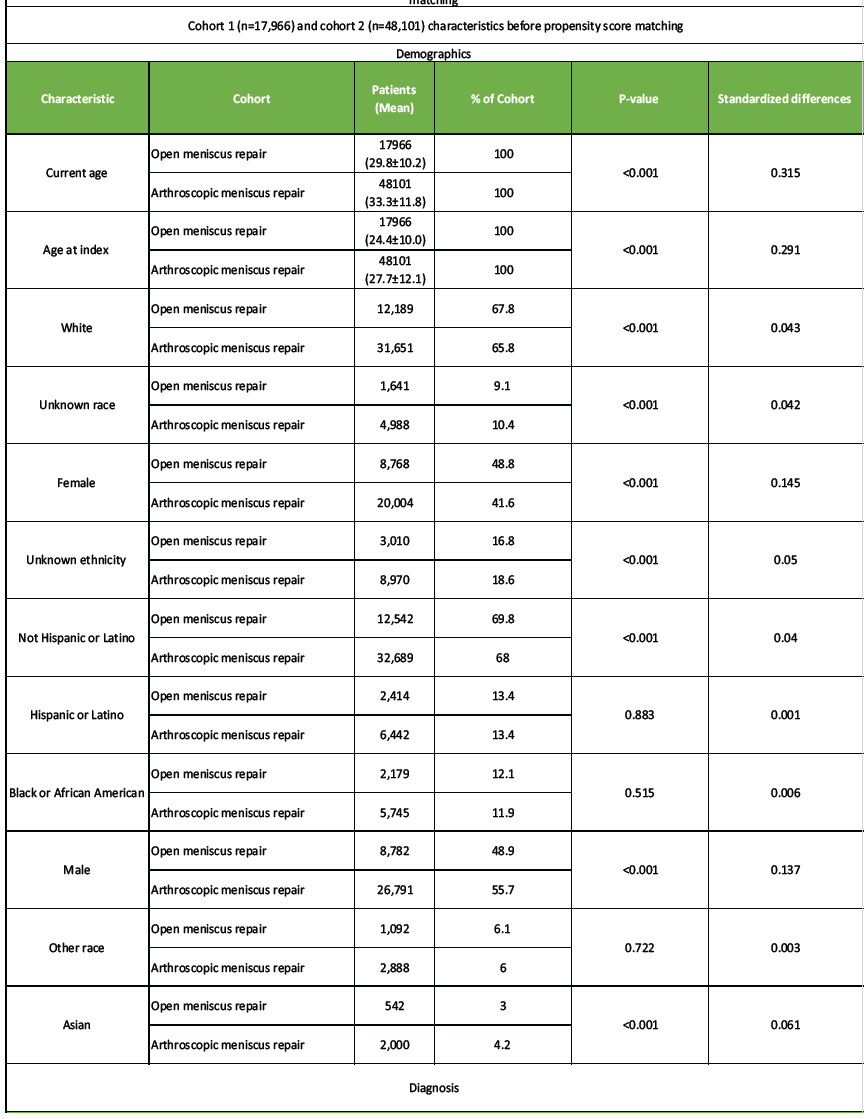

Cohorts and follow-up

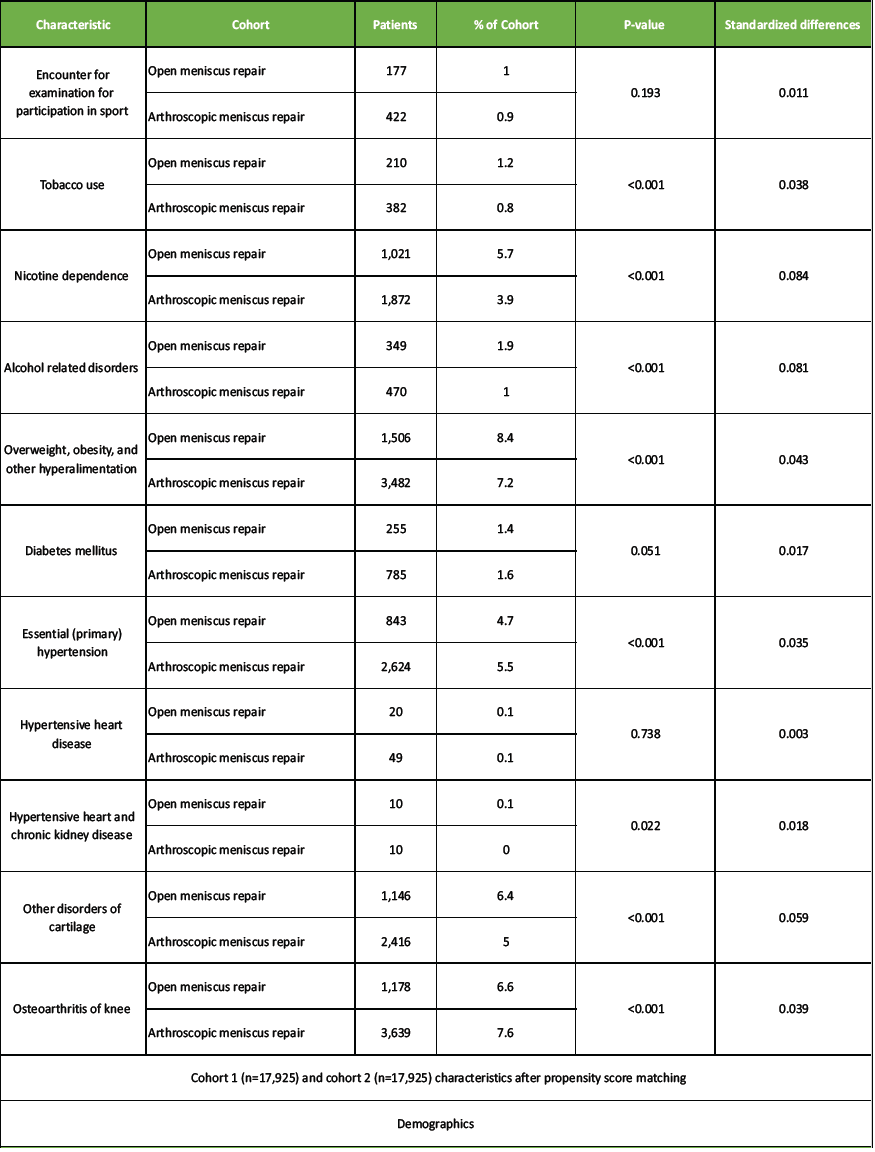

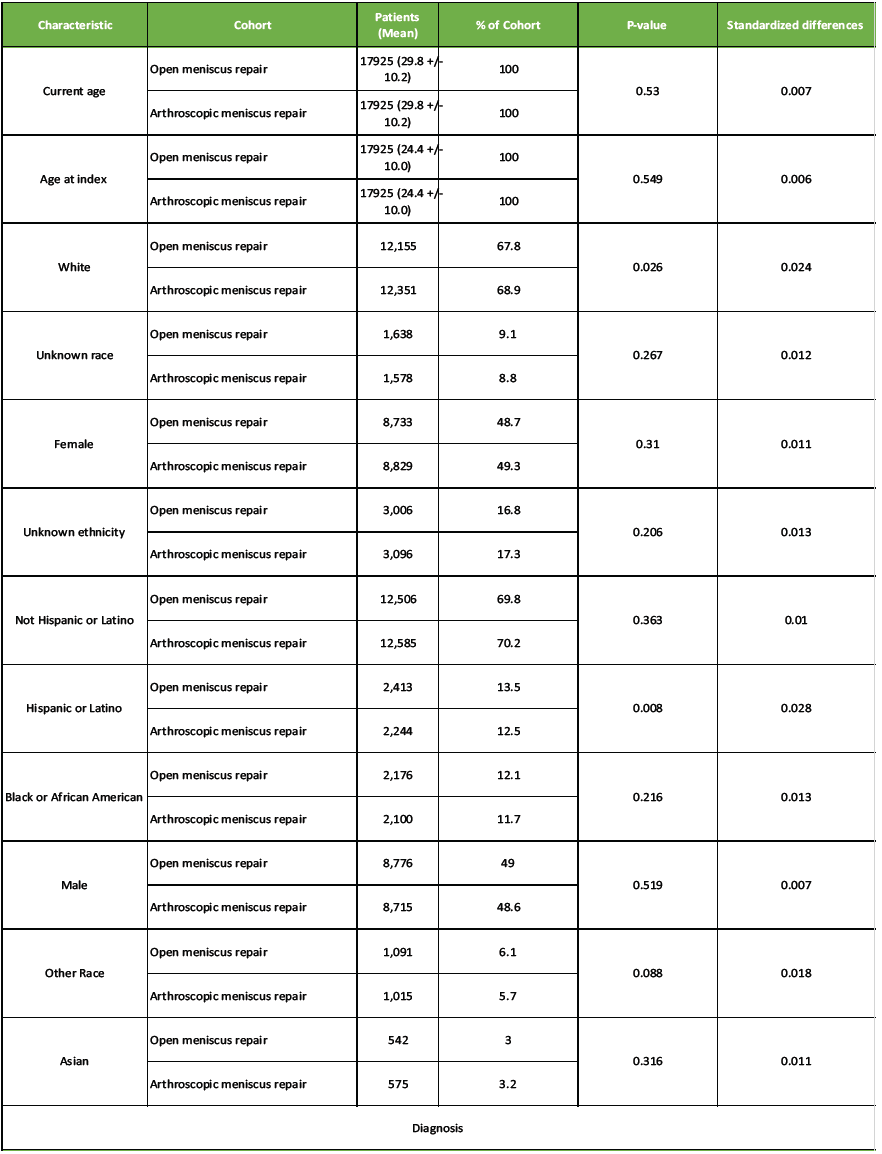

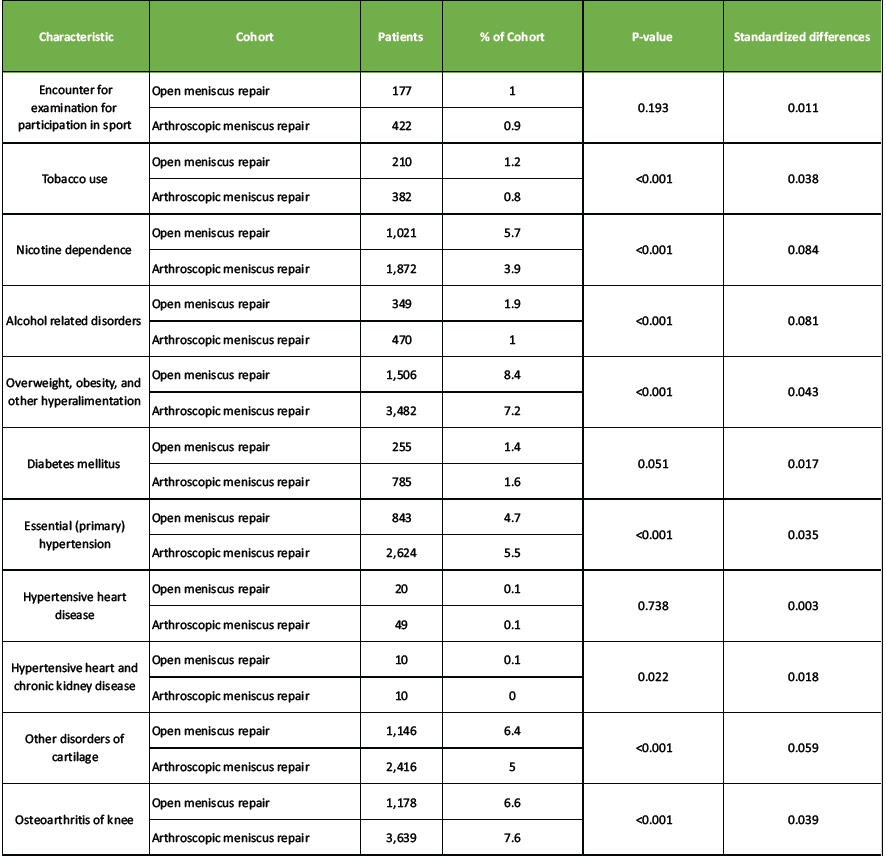

A total of 66,067 patients met inclusion criteria: 17,966 underwent open meniscus repair, and 48,101 underwent arthroscopic repair before PSM. Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in Table 1. Before matching, the arthroscopic group was slightly older (mean 33.3 ± 11.8 years) compared with the open group (29.8 ± 10.2 years), a difference of 3.5 years that was statistically significant (P < 0.001; standardized difference 0.315). Sex distribution also differed, with more females in the open group (48.8% vs. 41.6%) and more males in the arthroscopic group (55.7% vs. 48.9%, P < 0.001). Racial and ethnic compositions were broadly comparable (about two-thirds White, 12% Black), with trivial standardized differences (<0.05), though many reached statistical significance due to large sample sizes. In terms of comorbidities, the open cohort had slightly higher rates of tobacco use (1.2% vs. 0.8%), nicotine dependence (5.7% vs. 3.9%), and obesity (8.4% vs. 7.2%), while the arthroscopic group had marginally higher hypertension (5.5% vs. 4.7%). These imbalances underscored the need for adjustment.

After 1:1 PSM, 17,925 patients remained in each cohort, with excellent covariate balance. Post-match, the mean age was identical at 29.8 years in both groups (P = 0.53; standardized difference 0.007). The male proportion was 49.0% in the open cohort versus 48.6% in the arthroscopic cohort (P = 0.52). Race and ethnicity distributions were also balanced (e.g., White 67.8% vs. 68.9%, P = 0.03, standardized difference 0.024). No standardized difference exceeded 0.03, and most P-values were >0.2, confirming successful matching (Table 1, “After PSM”).

Median follow-up after matching was 653 days (~21.5 months) for the open cohort and 651 days (~21.4 months) for the arthroscopic cohort, with no significant difference. Mean follow-up was approximately 504 days in open repair patients and 502 days in arthroscopic patients. Fewer than 5% of patients were censored before 730 days, ensuring adequate observation of outcomes across both groups.

Table 1: Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients undergoing open versus arthroscopic meniscus repair before and after propensity score matching

Outcomes

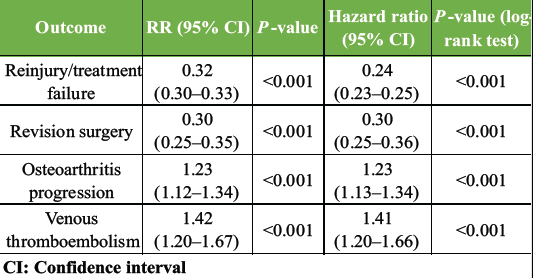

All outcomes reported are based on the matched cohorts (n = 17,925 per group). Risk values represent cumulative incidence over 2 years. Results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Comparative two-year outcomes of open versus arthroscopic meniscus repair after propensity score matching

Meniscal repeated tear or repair failure

Re-tear or failure was substantially more common following arthroscopic repair. By 2 years, 51.4% of arthroscopic patients experienced a recurrent tear compared to 16.2% of open repair patients. The risk ratio (RR) was 0.32 (95% CI 0.30–0.33; P < 0.001), indicating the risk in open repair patients was about one-third that in arthroscopic patients. Median time to failure in the arthroscopic group was 268 days (9 months), whereas the open cohort maintained 82% failure-free survival at 2 years. The HR was 0.24 (95% CI 0.23–0.25; P < 0.001), suggesting a 76% lower instantaneous hazard of failure after open repair.

Revision surgery

Revision surgery occurred in 1.0% of open repair patients compared with 3.4% of arthroscopic patients within 2 years. The RR was 0.30 (95% CI 0.25–0.35; P < 0.001), representing a 70% reduction in revision surgery risk with open repair. Kaplan–Meier curves showed early divergence by ~6 months, with persistent higher reoperation rates in the arthroscopic group. The HR for revision surgery was 0.29 (95% CI 0.25–0.35; log-rank P < 0.001). These findings indicate substantially greater surgical durability of open repair, with arthroscopic repair patients over 3 times more likely to require another meniscal procedure within 2 years.

Knee OA progression

Progression of knee OA was slightly more frequent in the open cohort. By 2 years, 6.1% of open repair patients developed new or worsening OA compared with 4.9% in the arthroscopic group. This corresponds to a RR of 1.23 (95% CI 1.12–1.34; P < 0.001) and an absolute risk difference of 1.2%. OA-free survival at 2 years was 92.0% in open patients versus 93.4% in arthroscopic patients. The HR was 1.23 (95% CI 1.12–1.34). The log-rank test (χ² = 20.7, P < 0.001) confirmed the statistical significance of the difference. Median time to OA could not be determined because >90% of both groups remained free of OA events by 2 years. These findings suggest that while open repair reduced meniscal failure, it was associated with a modestly increased risk of OA progression.

VTE

VTE events were rare but more frequent in the open group. Within 2 years, 1.9% of open repair patients developed VTE compared with 1.4% of arthroscopic patients. The RR was 1.42 (95% CI 1.20–1.67; P < 0.001), with an absolute risk difference of 0.5%. The HR was 1.41 (95% CI 1.20–1.66; log-rank P < 0.001). Kaplan–Meier curves showed significant separation. Although absolute rates were low (<2% in both groups), open repair carried a 40% higher risk ratio of post-operative thromboembolic complications.

Our findings indicate that open meniscal repair confers a substantially lower risk of re-tear and revision surgery than arthroscopic repair over a 2-year period in matched patients. Specifically, the risk of meniscal failure or re-injury was reduced by approximately two-thirds (RR 0.32, HR 0.24), and the risk of revision surgery was similarly reduced (RR 0.30, HR 0.29). These effect sizes are striking, suggesting a substantial durability benefit for open repair in routine practice. When contextualized against existing literature, the failure rate observed in our open repair cohort (16.2%) is in close alignment with long-term open repair series that report failure rates between 16% and 29% [1,11]. In contrast, the >50% re-tear rate in the arthroscopic cohort greatly exceeds most pooled estimates of arthroscopic failure (commonly 15–25%) [7,8]. This discrepancy likely reflects differences in patient and tear selection, definitions of failure, and real-world heterogeneity in practice. Because our failure definition captured recurrent meniscal tear diagnoses (irrespective of confirmation by imaging or surgery), it may include symptomatic degenerative tears beyond pure repair failure. The biomechanical rationale for lower failure in open repair may stem from more robust suture passage and direct visualization of the repair site, reducing malplacement or suboptimal anchor tensioning inherent to all-inside devices. In open repair, surgeons can place sutures under direct vision with full control, reducing technical variability. This is consistent with views that open repair retains a niche role when precision and durable fixation are paramount [6,10]. The trade-off is invasiveness: we observed slight increases in OA progression and VTE in the open cohort (OA RR 1.23, VTE RR 1.42). While statistically significant, these differences are modest in absolute terms and likely reflect the increased surgical dissection and possibly delayed mobilization after open repair.

Our observed OA progression rate of 6.1% at 2 years in open repair patients is lower than commonly cited rates after meniscectomy, which often exceed 20–30% at intermediate follow-up [9,12,13]. The fact that OA progression remains modest supports the notion that meniscal preservation, particularly through durable repair, mitigates long-term degeneration risk. The slightly higher OA risk in open repair likely reflects baseline lesion severity or prior cartilage damage rather than the repair modality per se, but merits consideration in surgical planning. Thromboembolic risk is a known albeit rare complication in orthopedic knee surgery; the observed 0.5% absolute difference should reinforce the need for prophylaxis and early mobilization [14,15]. Importantly, our large cohort and propensity matching help offset biases inherent in observational data. The matching balanced demographics and comorbidities, ensuring that the comparisons reflect the surgical approach rather than confounding factors. While unmeasured factors remain, the magnitude of the observed differences suggests a clinically meaningful superiority of open repair durability.

Limitations

Definition of failure was based on diagnostic codes for recurrent meniscal tears, not imaging or surgical confirmation; this may overestimate “true” repair failures. Unmeasured confounding remains possible (tear morphology, chronicity, meniscus vascularity, surgeon technical details, rehabilitation protocols). Procedure heterogeneity within the arthroscopic group (inside-out, all-inside, etc.) and variability in open repair techniques were not captured. Follow-up duration limited to 2 years; longer-term failures beyond 2 years are not assessed (prior data show many failures after year 2). Population limitation – only adults 18–60; pediatric or geriatric outcomes may differ. Generalizability to non-US settings is uncertain given regional practice variation in surgical technique, rehabilitation, and case mix.

Generalizability

The large and diverse dataset across many health centers increases external validity for adult meniscal repair in real-world practice. However, caution is warranted in applying findings to children, older adults, or centers with different surgical standards. The open repair cohort likely represents a subset of surgeons who maintain open techniques; centers without open repair expertise may not replicate these results. Moreover, given practice pattern differences internationally, surgeons should interpret these results in the context of their own patient population, tear patterns, and technical resources.

In this large real-world comparison, open meniscal repair was associated with substantially lower rates of re-tear and revision surgery compared to arthroscopic repair over 2 years, albeit with slight increases in OA progression and thromboembolism. These findings suggest that open repair may offer superior durability and lasting meniscal preservation, particularly in repairable tear patterns, and should remain a consideration rather than being entirely supplanted by arthroscopic methods. Shared decision-making, weighing the risks and benefits, is essential, and further prospective studies with detailed tear characterization and longer follow-up are needed to refine repair strategies.

Open meniscus repair provides greater long-term repair durability than arthroscopic repair, but with slightly higher risks of osteoarthritis progression and thromboembolic events. Surgeons should individualize treatment decisions based on patient age, activity level, and comorbidity profile. Careful perioperative management and shared decision-making are essential to optimize outcomes and minimize complications.

References

- 1. Cabarcas B, Peairs E, Iyer S, Ina J, Hevesi M, Tagliero AJ, et al. Long-term results for meniscus repair. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2025;18:229-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Sedgwick MJ, Saunders C, Getgood AM. Systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes following meniscus repair in patients 40 years and older. Orthop J Sports Med 2024;12:23259671241258974. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. DeFroda S. Editorial commentary: Meniscal repair, when possible, is better for patients than meniscectomy. Arthroscopy 2022;38:2884-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Hanks GA, Gause TM, Sebastianelli WJ, O’Donnell CS, Kalenak A. Repair of peripheral meniscal tears: Open versus arthroscopic technique. Arthroscopy 1991;7:72-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Cavendish PA, Coffey E, Milliron EM, Barnes RH, Flanigan DC. Horizontal cleavage tear meniscal repair using all-inside circumferential compression sutures. Arthrosc Tech 2023;12:e1319-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Kang DG, Park YJ, Yu JH, Oh JB, Lee DY. A systematic review and meta-analysis of arthroscopic meniscus repair in young patients: Comparison of all-inside and inside-out suture techniques. Knee Surg Relat Res 2019;31:1-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Odeh J, Al Maskari S, Raniga S, Al Hinai M, Mittal A, Al Ghaithi A. Good clinical success rates are seen 5 years after meniscal repair in patients regularly undertaking extreme flexion. Arthroscopy Sports Med Rehabil 2021;3:e1835-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Chand SB, Pifer T, Martinez S, Miller C, Epperson R, Jones B, et al. Efficacy and long-term outcomes of arthroscopic meniscus repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cureus 2024;16:e70828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Weber J, Koch M, Angele P, Zellner J. The role of meniscal repair for prevention of early onset of osteoarthritis. J Exp Orthop 2018;5:10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ozeki N, Seil R, Krych AJ, Koga H. Surgical treatment of complex meniscus tear and disease: State of the art. J ISAKOS 2021;6:35-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Ow ZG, Law MS, Ng CH, Krych AJ, Saris DB, Debieux P, et al. All-cause failure rates increase with time following meniscal repair despite favorable outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthroscopy 2021;37:3518-28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Hurmuz M, Ionac M, Hogea B, Miu CA, Tatu F. Osteoarthritis development following meniscectomy vs. meniscal repair for posterior medial meniscus injuries: A systematic review. Medicina (Kaunas) 2024;60:569. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Wu M, Su Q, Zhao Q, Liu S. Evidence-based weight-bearing protocols after meniscal repair: Balancing functional recovery and healing safety across injury types. J Orthop Surg Res 2025;20:604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Wang H, Man Q, Gao Y, Xu L, Zhang J, Ma Y, et al. The efficacy of medial meniscal posterior root tear repair with or without high tibial osteotomy: A systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2023;24:464. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Bottomley J, Al-Dadah O. Arthroscopic meniscectomy vs meniscal repair: Comparison of clinical outcomes. Cureus 2023;15:e44122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]