The route of TXA administration plays a significant role in its efficacy in reducing perioperative blood loss. The combined (IV+ Topical) route is more effective in reducing intraoperative and post-operative blood loss as compared to IV or Topical routes.

Dr. Sanjeev Chincholi, Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad - 244001, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: chincholi1969@gmail.com

Introduction: Perioperative blood loss is a significant challenge in total hip arthroplasty (THA), and it often necessitates blood transfusion. Tranexamic acid (TXA), an antifibrinolytic agent, is widely used to reduce surgical blood loss, but to date; there is no clear consensus on the optimal and most efficacious route of administration of TXA. Therefore, this study was planned to evaluate and compare the efficacy of different routes of administration of TXA in reducing perioperative blood loss through a prospective comparative study.

Materials and Methods: A total of 102 patients undergoing elective unilateral THA were enrolled and randomized into three cases and their three control groups of 17 patients each. The patients in group A (intravenous [IV]-TXA group) received IV-TXA while its control Group D received an equivalent amount of IV normal saline (NS). Group B (Topical-TXA group), received topical TXA, while its control Group E received an equivalent amount of NS at similar stages in a similar fashion. Group C (combined-TXA group) received IV as well as topical TXA, while its control Group F received an equivalent amount of NS at similar stages. Perioperative blood loss was measured from suction cylinders, mop weight and drain output. Statistical analysis included analysis of variance, post hoc Tukey tests, and independent t-tests.

Results: All TXA groups showed reduced blood loss as compared to their controls. Among these, the combined-TXA group demonstrated the lowest total mean blood loss (629.29 ± 26.33 mL), followed by the IV-TXA and topical-TXA group. These differences were statistically significant (P < 0.05). No adverse events were reported in the case or control groups.

Conclusion: The route of TXA administration plays a significant role in its efficacy in reducing perioperative blood loss. The combined (IV+ Topical) route is more effective in reducing intraoperative and post-operative blood loss as compared to IV or topical routes.

Keywords: Tranexamic acid, total hip arthroplasty, perioperative blood loss.

One of the common challenges associated with total hip arthroplasty (THA) is substantial perioperative blood loss, which can reach up to 2000 mL and often necessitates blood transfusion [1]. While there is a growing global trend toward minimally invasive procedures across surgical disciplines, THA still lacks a universally accepted approach that effectively minimizes blood loss. As a result, pharmacological interventions remain essential [2,3]. While meticulous hemostasis is the cornerstone in minimizing blood loss, pharmacological measures such as tranexamic acid (TXA) injections can also play a significant role. There have been multiple studies in the literature reporting significant reductions in blood loss after TXA administration. Among these studies, the routes of TXA administration include oral, intravenous (IV), topical, or a combination of these [2,3,4,5,6]. However, still, there is no consensus on the most effective route of administration [2,3,4,5,7,8]. Therefore, this study was planned to evaluate and compare the efficacy of different modes of administration of TXA in reducing intraoperative and post-operative blood loss through a triple-blinded randomized controlled trial.

This prospective comparative study was carried out at a tertiary care center located in north India, over a period of 18 months from December 2023 to May 2025. Before study initiation, ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the University vide number TMU/IEC/NOVEMBER/23/113.

Sampling method

A total of 102 patients scheduled for elective unilateral THA who met the inclusion criteria were selected using a lottery method and randomly assigned into six groups based on different modes of TXA administration. The sample size was determined using previously reported means and standard deviations (SD), with calculations based on a 99% confidence level and 80% power, resulting in a minimum of 17 participants per group.

Randomization and blinding

After explaining the study procedures, implications, and purpose, written informed consent was obtained from selected study participants. The consenting patients aged between 18 and 65 years of age, possessing a baseline hemoglobin (Hb) level ≥10 g/dL and a packed cell volume (PCV) over 33% undergoing THA for primary osteoarthritis, secondary osteoarthritis due to sequelae of septic hip, avascular necrosis, healed tuberculosis, and post-traumatic arthritis were included. Patients were excluded if they had thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000/mm3), had chronic conditions associated with a high risk of bleeding, anemia (Hb <10 g/dL, PCV <33%), were on thrombolytic or anticoagulant therapy. Apart from this, patients undergoing THA for acute trauma were also excluded from the study.

All enrolled patients were randomly allocated into a total of 6 groups (N-17 each) using a computer-generated sequence. See Fig. 1 for the flow chart of recruitment and group allocation process.

Figure 1: Consort 2010 flow diagram.

Out of these six groups, three were case groups (Group A, Group B and Group C) with three corresponding control groups (Group D, Group E and Group F) for respective case groups. All patients were operated on under spinal anesthesia at a single center in a lateral position using the posterior approach to the hip joint by the same senior arthroplasty surgeon. Neither the operating surgeon nor the participants were made aware if they were getting TXA or Placebo normal saline (NS). Furthermore, to prevent bias, the data collectors and data analysts were also blinded to the group assignments so they did not know if they were analyzing the data of a control group or a case group.

Experimental procedure

The patients in group A (IV-TXA group) (n = 17) received IV-TXA at a dose of 15 mg/kg, administered 5 min before the skin incision while the control Group D (n = 17) received an equivalent amount of IV-NS.

For group B (Topical-TXA group), three grams of TXA were diluted in 150 mL NS and divided into three parts of 50 mL each. Sterile gauze pieces were soaked in this solution. These TXA-saline soaked Gauze pieces were applied topically at three procedural stages: (1) In the reamed acetabulum, before cup placement the gauze pieces containing 50 mL of TXA were applied for 3 min; (2) after femoral reaming, before stem insertion, the gauze pieces containing 50 mL of TXA were packed in the femoral canal for 3 min. (3) The remaining 50 mL of the prepared solution was infiltrated into and around the hip joint after fascia closure. The corresponding control Group E received an equivalent amount of NS at similar stages in a similar fashion. The preparation and administration of TXA or placebo (NS) were performed by an independent anesthesiologist not involved in the surgical procedure or outcome assessment. Identical coded syringes/containers were used, ensuring that the operating surgeon, patient, data collector, and analyst remained blinded to the allocation throughout the study.”

Measurement of blood loss

Intraoperative blood loss was measured by assessing the volume collected in suction cylinders, excluding NS, and by weighing surgical mops using a calibrated electric weighing scale (Alexandra Scale; accuracy 0.1 mg). Each mop (approx. 9 × 9 cm) had an average dry weight of 25 g. Blood absorbed in mops was calculated as:

(Weight of used mops – Weight of dry mops) × Number of mops × Conversion factor (mL/g) [9].

Post-operative blood loss was assessed by measuring hemoglobin and hematocrit levels 48 h after drain removal. Blood loss was estimated using the Gross formula, as represented as follows:

Estimated blood loss = Estimated blood volume × (Initial hematocrit – Final hematocrit)/Mean hematocrit, where Estimated blood volume = Body weight (kg) × 70 mL/kg [10].

Statistical analysis

The data were compiled in Microsoft Excel 2024. Categorical variables were expressed as absolute frequencies and corresponding percentages, while continuous variables were summarized as mean ± SD. For inter-group comparisons of quantitative data, analysis of variance was employed, whereas associations between qualitative variables were assessed using the Chi-square test. Further Post hoc Tukey analysis was done wherever required. A P < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Statistical analyses were conducted utilizing the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). The study findings were further interpreted in the context of existing literature by comparing them with outcomes reported in previously published studies.

Out of a total of 102 enrolled patients, 53 were male, and 49 were female. The mean age was 41.5 years, ranging from 18 to 65 years. It was observed that though there was a reduction in the hemoglobin and hematocrit levels in the post-operative period in all the case groups and their corresponding controls, it was not found to be statistically significant (P > 0.05).

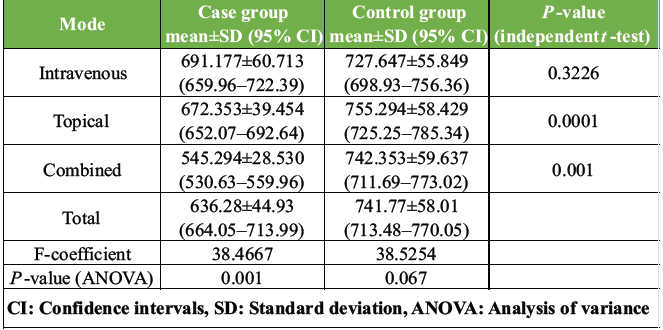

Intraoperative blood loss

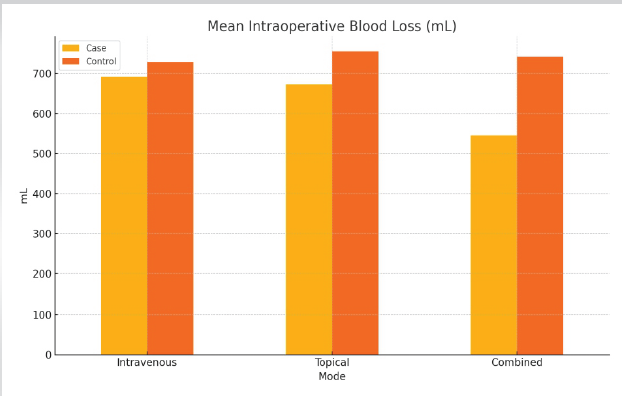

We observed that the mean intraoperative blood loss was consistently lower across all case groups as compared to their corresponding control groups. The overall mean blood loss in the case groups was 636.28 ± 44.93 mL, whereas in the control group, it was 741.77 ± 58.01 mL. Furthermore, we observed that among all three case groups, the combined- TXA group had a maximum reduction in intraoperative blood loss when compared to the corresponding control group (P < 0.05) whereas the topical-TXA group showed the least reduction (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1: Comparison of mean intraoperative blood loss and 95% confidence intervals in brackets, between case and control groups

Figure 2: Graph showing that the mean intraoperative blood loss was consistently lower across all case groups as compared to their corresponding control group. The combined tranexamic acid group had a maximum reduction in intraoperative blood loss.

Post hoc Tukey analysis further confirmed the statistically significant difference between the combined-TXA group with the IV and topical group (P < 0.05). However, no significant difference in the reduction of intraoperative blood loss was found between IV-TXA and topical-TXA groups.

Post-operative blood loss

There was a statistically significant difference in mean drain output across all case groups when compared to their respective control groups. The overall mean drain site blood loss in the case group was (17.16 ± 2.52) mL, whereas in the control group, it was (30.57 ± 4.52 mL). Among the three case subgroups, the combined-TXA group exhibited the lowest mean drain output (P < 0.05), indicating the least post-operative blood loss, followed by the topical group. The IV-TXA group showed the highest mean drain output among the case groups (Table 2 and Fig. 3). Post hoc Tukey analysis further suggested the pairwise differences, which were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.05).

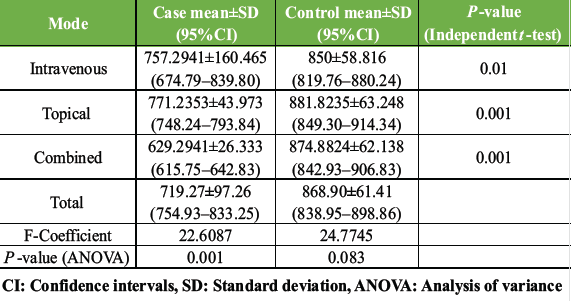

Table 2: Mean total blood loss (mL) and 95% confidence intervals in brackets

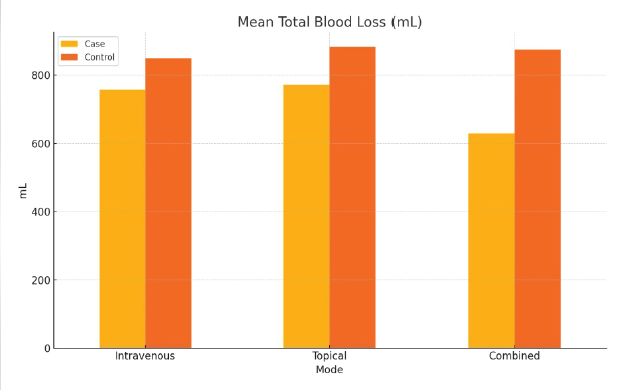

Figure 3: Graph showing the difference in the mean total blood loss between the case and control groups. The combined tranexamic acid group had the lowest mean total blood loss (P < 0.05).

Total blood loss

A statistically significant reduction in mean total blood loss was observed across all case groups compared to their respective control groups. The overall mean total blood loss in the case group was (719.27 ± 97.26 mL), whereas in the control group it was (868.90 ± 61.41 mL). Among the three intervention subgroups, the combined-TXA group demonstrated the lowest mean total blood loss (P < 0.05), indicating the greatest efficacy in minimizing perioperative blood loss, followed by the topical group. Post hoc Tukey analysis further suggestive of no statistically significant difference in mean total blood loss between the IV and topical group (P > 0.05), whereas there was a statistically significant difference in mean total blood loss of combined-TXA group with the IV-TXA and topical-TXA group (P < 0.05).

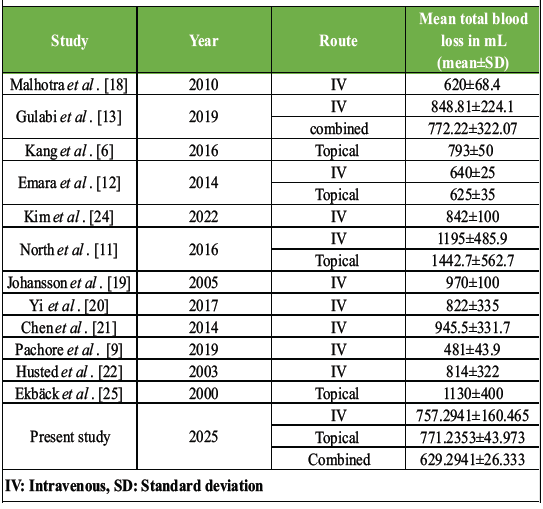

It has been concluded in many studies that the route of administration of TXA plays a significant role in its efficacy in minimizing perioperative blood loss [2, 5, 7, 11, 12, 13, and 14]. However, there is still no clear consensus about the most effective route of administration of TXA. For example, in the study done by Lu et al., it was concluded that the combined IV+ topical route of TXA is more effective in minimizing perioperative blood loss [7]. In another study, Poursalehian et al. reported that IV+ topical route is inferior than IV+ Oral TXA in minimizing perioperative blood loss [2]. Similarly, there are a few studies which have reported that the combined route of administration of TXA is not better than any single route in minimizing perioperative blood loss [3,15]. Our study was an attempt to answer this ongoing debate on the effect of the route of administration of TXA on its effect in reducing perioperative blood loss. We observed that the route of TXA administration plays a significant role in its efficacy in reducing perioperative blood loss. In our study, the combined (IV+ topical) route more effectively reduced intraoperative and post-operative blood loss as compared to IV or topical routes (P < 0.05). After the combined route, the topical route was found to be more effective in reducing mean total blood loss in THA, and the IV route was found to be the least effective. However, the difference between IV and topical routes was not found to be statistically significant on post hoc Tukey analysis. A comparison of the results of the present study with past studies is given in Table 3.

Table 3: Comparison of present study parameters with past studies

The cases in the combined-TXA group received TXA 15 mg/kg IV along with 800 mg TXA directly into the raw surface of the wound. In the combined TXA group, along with IV, the topically administered TXA further increases the local concentration of TXA at the surgical site, increasing the hemostatic effects. The findings of our study are similar to the findings of a study done by Majumdar et al. (IV+ topical), Lu et al., Poursalehian et al. and Gulabi et al. [2,5,7,13]. All four of these studies have reported less total blood loss in the cases that got TXA through combined route [2,5,7,13]. Lu et al. in their meta-analysis, which included 14 studies, compared the effect of the combined route of (IV+ topical) and concluded that the combined route had significantly reduced total blood loss compared with any of the single regimens [7]. Poursalehian et al. in their meta-analysis also reported the same findings. Another notable finding in their study was that oral TXA in combination with intra-articular (topical) administration demonstrated even better efficacy in reducing blood loss and transfusion rates as compared to other routes such as IV+ topical [2]. The combined-TXA group in the study done by Gulabi et al. [13] had a mean total blood loss of 772.22 ± 322.07, which is higher than the mean total blood loss in the combined-TXA group (629.2941 ± 26.333) of our study. However, their technique of TXA administration, dosage, and concentration of the solution was different from our study. In our study, 15 mg/kg of TXA was given IV 5 min before incision, followed by topical applications of 20 mL (200 mg) at the acetabulum and femoral canal, and 60 mL (600 mg) into and around the joint after fascia closure. Whereas in the study done by Gulabi et al., TXA was administered 1 g TXA dissolved in 100 mL NS IV and infused over 30 min before the skin incision, and the same dose was repeated 3 h later [13]. In addition to the above, 3 g of TXA diluted in 30 mL NS was injected intra-articularly after closure of the arthrotomy [13]. Authors are not sure whether this difference in the result was because of dosage, concentration of the TXA or the technique of TXA application. The topical route provided inferior results in terms of intraoperative, post-operative and total blood loss as compared to the combined route, which is in accordance with the results of the meta-analysis done by Liu and Lee [14]. The one interesting finding in our study was that the topical route was found to be significantly better than IV route for minimizing post-operative drain site blood loss (P < 0.05). However, for minimizing intraoperative blood loss, this difference was found to be insignificant (P < 0.05). Although the topical route provides an inferior reduction in perioperative blood loss when compared to the combined route, it is still a viable option in high-risk cases of thromboembolism, as the reduced systemic concentration of the TXA can avoid systemic thromboembolic complications. In the present study, the patients who received TXA, irrespective of the route of administration had less intraoperative, post-operative, and total blood loss as compared to a control group who received NS. This makes it quite evident that irrespective of the route, TXA is better than placebo when it comes to minimizing perioperative blood loss. Several other studies in the literature have also reported similar findings [2,3,5,6,7,8,14,16,17]. Collectively, these results reinforce the role of the route of TXA administration. The combined-TXA route provides superior results, followed by IV-TXA in reducing perioperative blood loss in cases of THA. The topical route demonstrated a higher trend toward minimizing perioperative blood loss as compared to the IV route; however, it was not found to be statistically significant. In our study, the mean total blood loss in the IV-TXA group was 757.2941 ± 160.465 mL, which is less than the other studies that used the IV route in the past (Table 1). Only the study done by Pachore et al. [9] (481.4 ± 43.9 mL) and Emara et al. [12] (640 ± 25 mL) showed lesser blood loss than our study. As all the patients underwent hemiarthroplasty in the study done by Emara et al. [12], which needs less dissection and takes lesser surgical time, the lesser blood loss is explainable. Pachore et al. [9] reported lesser blood loss by using 10 mg/kg of TXA IV. However, as it was not a triple-blinded study, the validity of their results remains in question. The topical route in the present study shows lower total mean blood loss (771.23 ± 43.973 mL) as compared to most of the previous studies (Malhotra et al. [18], Gulabi et al. [13], Kang et al. [6], Emara et al. [12], North et al. [11], Johansson et al. [19], Yi et al. [20], Chen et al. [21], Pachore et al. [9], and Husted et al. [22]). Only the study done by Emara et al. [12] reported a lower mean total blood loss (625 ± 35 mL) as compared to the present study. Another difference between the present study and the study of Emara et al. [12] was in the technique of TXA application. The patients in the current study received 2% TXA (total of 3 g) in three parts of 50 mL each at three stages (before cup placement, before stem insertion and before wound closure) during the surgery. Whereas the patients in the study done by Emara et al. received a total of 1.5% solution (total 1.5 g TXA) into the surgical field and left for 5 min before wound closure [12]. However, the authors are not sure if this difference in the technique was actually the reason behind the difference in the results. TXA is known to be associated with certain side effects such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, visual disturbances, renal failure, and in rare cases, thromboembolic events [19]. However, in our study, no such side effects were observed in any patients of the case or control group. The strength of this study is that it was a triple-blinded study. Selection bias was reduced by randomization, and performance bias was avoided by blinding the patient. Observer bias was reduced by blinding the investigator, and detection bias was reduced by blinding the data analyst. To reduce the potential confounding effect of surgical technique on perioperative pain, all procedures were performed by a single experienced surgeon. This approach ensured consistency in surgical execution and minimized the influence of technique-related variability on hemostasis and perioperative blood loss. As the threshold of blood transfusion varies between surgeons and hospitals, its incidence cannot be taken as an actual measurement of blood loss. Hence, to determine the actual effect of TXA, direct measurement of blood loss was preferred over blood transfusion parameters. This study had several limitations that warrant consideration. To begin with, the study has a relatively small sample size and a limited follow-up duration. Secondly, as the study was performed at a single center, the generalizability of the results to the broader population is limited. To address this, we recommend further multicenter prospective studies and clinical trials encompassing diverse geographic and demographic populations. In addition, as clearance of TXA may vary in patients of different age groups, comprehensive pharmacokinetic and dosing studies across different age groups are necessary [23]. Finally, although TXA is presumed to reduce perioperative transfusion-related costs, this study did not include a formal cost-benefit analysis. Future research should incorporate economic evaluations to better assess the financial implications of TXA use in THA. Moreover, the findings of this study are specific to adult patients undergoing elective, unilateral THA. The applicability of TXA in bilateral procedures, where blood loss is typically more substantial, or in emergent surgical settings, remains to be established. Similarly, the efficacy and safety profile of TXA in pediatric patients undergoing THA is insufficiently understood and warrants further investigation.

This study concludes that the route of TXA administration plays a significant role in its efficacy in reducing perioperative blood loss. The combined-TXA route is more effective in reducing intraoperative and post-operative blood loss as compared to IV-TXA or Topical-TXA routes. Moreover, irrespective of any route of administration, TXA is better than a placebo in minimizing perioperative blood loss. Thus, TXA should be used preferably through a combined route in the cases of THA to reduce perioperative blood loss.

Administration of TXA effectively reduces perioperative blood loss in THA, with the combined route being superior to IV or topical administration. Regardless of route, TXA is more effective than placebo.

References

- 1. Ethgen O, Bruyère O, Richy F, Dardennes C, Reginster JY. Health-related quality of life in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. A qualitative and systematic review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:963-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Poursalehian M, Tajvidi M, Ghaderpanah R, Soleimani M, Hashemi SM, Kachooei AR. Efficacy and safety of oral tranexamic acid vs. other routes in total joint arthroplasty: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. JBJS Rev 2024;12:11-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Fillingham YA, Ramkumar DB, Jevsevar DS, Yates AJ, Shores P, Mullen K, et al. The efficacy of tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty: A network meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:3083-9.e4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Colomina MJ, Contreras L, Guilabert P, Koo M, Ndez EM, Sabate A. Clinical use of tranexamic acid: Evidences and controversies. Braz J Anesthesiol 2022;72:795-812. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Majumdar PK, Goyal G, Kumar V, Potalia R, Roy S, Punia P. Evaluation of efficacy of tranexamic acid on blood loss in surgically managed intertrochanteric fractures. J Orthop Case Rep 2025;15:287-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Kang JS, Moon KH, Kim BS, Yang SJ. Topical administration of tranexamic acid in hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop 2017;41:259-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Lu F, Sun X, Wang W, Zhang Q, Guo W. What is the ideal route of administration of tranexamic acid in total knee arthroplasty? A meta-analysis based on randomized controlled trials. Ann Palliat Med 2021;10:1880-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Duan Y, Wan X, Ma Y, Zhu W, Yin Y, Huang Q, et al. Application of high-dose tranexamic acid in the perioperative period: A narrative review. Front Pharmacol 2025;16:1552511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Pachore JA, Shah VI, Upadhyay S, Shah K, Sheth A, Kshatriya A. The use of tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in uncemented total hip arthroplasty for avascular necrosis of femoral head: A prospective blinded randomized controlled study. Arthroplasty 2019;1:12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Gross JB. Estimating allowable blood loss: Corrected for dilution. Anesthesiology 1983;58:277-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. North WT, Mehran N, Davis JJ, Silverton CD, Weir RM, Laker MW. Topical vs intravenous tranexamic acid in primary total hip arthroplasty: A double-blind, randomized controlled trial. J Arthroplasty 2016;31:1022-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Emara WM, Moez KK, Elkhouly AH. Topical versus intravenous tranexamic acid as a blood conservation intervention for reduction of post-operative bleeding in hemiarthroplasty. Anesth Essays Res 2014;8:48-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Gulabi D, Yuce Y, Erkal KH, Saglam N, Camur S. The combined administration of systemic and topical tranexamic acid for total hip arthroplasty: Is it better than systemic? Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2019;53:297-300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Liu HW, Lee SD. Impact of tranexamic acid use in total hip replacement patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Orthop 2025;60:125-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Ghorbani M, Sadrian SH, Ghaderpanah R, Neitzke CC, Chalmers BP, Esmaeilian S, et al. Tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty: An umbrella review on efficacy and safety. J Orthop 2024;54:90-102. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Tanaka N, Sakahashi H, Sato E, Hirose K, Ishima T, Ishii S. Timing of the administration of tranexamic acid for maximum reduction in blood loss in arthroplasty of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:702-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Dang X, Liu M, Yang Q, Jiang J, Liu Y, Sun H, et al. Tranexamic acid may benefit patients with preexisting thromboembolic risk undergoing total joint arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EFORT Open Rev 2024;9:467-78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Malhotra R, Kumar V, Garg B. The use of tranexamic acid to reduce blood loss in primary cementless total hip arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2011;21:101-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Johansson T, Pettersson LG, Lisander B. Tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty saves blood and money: A randomized, double-blind study in 100 patients. Acta Orthop 2005;76:314-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Yi Z, Bin S, Jing Y, Zongke Z, Pengde K, Fuxing P. Tranexamic acid administration in primary total hip arthroplasty: A randomized controlled trial of intravenous combined with topical versus single-dose intravenous administration. JBJS 2016;98:983-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Chen S, Wu K, Kong G, Feng W, Deng Z, Wang H. The efficacy of topical tranexamic acid in total hip arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2016;17:81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Husted H, Blønd L, Sonne-Holm S, Holm G, Jacobsen T, Gebuhr P. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusions in primary total hip arthroplasty: A prospective randomized double-blind study in 40 patients. Acta Orthop Scand 2003;74:665-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Ehresman J, Pennington Z, Schilling A, Medikonda R, Huq S, Merkel KR, et al. Cost-benefit analysis of tranexamic acid and blood transfusion in elective lumbar spine surgery for degenerative pathologies. J Neurosurg Spine 2020;33:177-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Kim C, Park SS, Davey JR. Tranexamic acid for the prevention and management of orthopedic surgical hemorrhage: Current evidence. J Blood Med 2015;6:239-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Ekbäck G, Axelsson K, Ryttberg L, Edlund B, Kjellberg J, Weckström J, et al. Tranexamic acid reduces blood loss in total hip replacement surgery. Anesth Analg 2000;91:1124-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]