The learning point is to understand the importance of structured rehabilitation in both conservatively and surgically managed distal end radius fracture in adults. It will guide the orthopedic surgeons and physical therapists to plan effective, phase-wise management and incorporate recent advancements in rehabilitation for complete recovery, minimizing complications.

Dr. Sagar Deshpande, Neuro Physiotherapy Department School of Physiotherapy, D Y Patil (Deemed)to be University, Nerul, Navi Mumbai 400706 Consultant in D Y Patil Health Care Hospital, Nerul, Navi Mumbai, India. E-mail: sagar.deshpande@dypatil.edu

Introduction: From a physiotherapist’s point of view, helping patients recover from a distal end radius (DER) fracture is a big part of getting them back to their daily lives. This article highlights how important a structured, step-by-step rehabilitation program is for adults, whether their fracture was treated with a cast or with surgery. As physical therapists, our role is crucial in guiding this recovery, working closely with orthopedic surgeons.

Materials and Methods: We understand that there isnot one perfect exercise plan for every patient, but starting exercises early is always better. Our main goals are to reduce pain and swelling, improve how much the wrist and hand can move, and build up strength. We also focus on preventing common problems like stiffness or Complex Regional Pain Syndrome. We use tools like the Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand and Michigan Hand Questionnairescales to see how well patients are improving in their daily activities.

Discussion: The rehabilitation is divided into phases. In the early phase, we focus on protecting the fracture while keeping other joints moving and managing swelling. As the bone heals, we introduce exercises to get the wrist moving more, improve muscle strength, and help with balance and coordination. We use various techniques, from gentle mobilizations to resistance exercises, and sometimes advanced therapies like electrical stimulation or mirror therapy to help patients along.

Conclusions: For patients who have had surgery, the rehab principles are similar, but we adjust the timing of exercises based on the surgeon’s advice and the type of fixation. Ultimately, successful recovery is a team effort. When physical therapists and orthopedic surgeons work together, and the patient follows the plan, most people can regain good function and return to their normal activities after a DER fracture.

Keywords: Wrist, fracture,range of motion, pain,rehabilitation.

The distal end radius (DER) occurs at the metaphyseal region of the distal radius. It is seen most commonly in children or adolescents and elderly individuals. The type of fracture, management, and its complications differ in both the populations. Radial height, radial inclination, radial shift, volar tilt, ulnar variance, ulnar styloid fracture, and distal radio-ulnar joint widening should all be checked for during an X-ray examination. To improve short-term and long-term outcomes of wrist pain, range of motion (ROM), grip strength, and function, the physical therapists should be the primary instructors[1].There is no standard protocol established for wrist rehabilitation following a distal radius fracture, but literature review concludes that performing some exercises is always better than no exercises. This implies that rehabilitation following fracture plays an important role, thereby improving patient outcomes[2].After 1 year of rehabilitation, individuals gain independence in their activities of daily living andgain complete wrist and forearm ROM irrespective of the type of fixation and duration of immobilization. The patient outcome following a distal radius fracture is assessed using radiographs, strength testing, and patient-rated functional outcome measures. Two commonly used patient-rated functional outcome measures are the Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand (DASH) and Michigan Hand Questionnaire (MHQ) scales. Early involvement in rehabilitation can be beneficial to patients and may reduce the number of therapy sessions required to regain functional strength and motion[3].A systematic review conducted in 2015 suggests that many researchers have given different rehabilitation protocols for DER fracture;however, it is not possible to rely on one protocol only when treating a patient[4].A systematic review conducted in 2024 showed that early rehabilitation in DER fracture yielded better functional outcomes by reducing pain and improving wrist mobility[5].Each management protocol has its own benefits and plays a pivotal role in achieving functional recovery. The physical therapy management for an adult DER fracture is described below. These goals and interventions may change depending on the type of fixation, patient compliance, and the surgeon’s advice.

Rehabilitation in a conservatively managed DER fracture

Phase I: Early motion phase (0–4 weeks)

Goals of rehabilitation:

- To educate the patient about the fracture rehabilitation and its course for complete functional recovery

- To immobilize the wrist and forearm with a plaster cast

- To minimize pain and reduce swelling

- To maintain ROM at the shoulder, elbow, and cervical ROM

- To prevent complications like Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS)

- To maintain ROM at the wrist and interphalangeal joints

- To prevent wrist and finger stiffness

- To maintain scapular stability

- To improve aerobic capacity.

Bracing: Plaster cast from the above elbow to the metacarpal heads for fracture immobilization

Interventions:

- Elevation of the upper extremity above heart level

- Cryotherapy to reduce swelling by causing local vasoconstriction, reducing the activity of inflammatory mediators, and altering the cell permeability [6]

- Light ball squeezing and various gripping activities for long wrist and finger flexor strengthening

- Soft tissue mobilization to cervical and scapular muscles for relieving the spasm as a result of fracture immobilization that results in proximal muscle tightness and weakness

- Begin submaximal isometric muscle contractions for wrist flexors and extensors

- Scapula mobilization and retraction exercises to activate the scapular muscles

- Shoulder and elbow strengthening exercises using manual resistance

- Breathing exercises and walking areadvised for aerobic training

- Active ROM to the shoulder, cervical spine, elbow, and fingers

- Initiate pain-free passive ROM at 2 weeks for wrist, forearm, and hand

Phase II: Active motion phase (5–8 weeks)

Goals of rehabilitation:

- To maintain muscle property

- To reduce edema around the wrist joint

- To improve joint play at the radiocarpal joint

- To improve wrist and hand mobility

- To improve neuromuscular control at the wrist joint

- To increase the strength and endurance of forearm and hand muscles

- To maintain the flexibility of long wrist and hand flexors

- To restore scapula-humeral rhythm

Bracing: Post-reduction splint (remove the splint during exercises 2–3 times a day)

Interventions:

- Hot water fomentation to relax the muscles of forearm and hand (if the swelling is not present)

- Scapular stabilization exercises to improve the scapulohumeral rhythm (T-I-Y exercises)

- Edema reduction techniques including isotoner glove, edema mobilization, massage, and kinesiotaping

- Exercises to include desensitization (expose to different temperatures, textures, stimuli) and upper limb mobility exercises to prevent and manage CRPS

- Isometric muscle contraction exercises for wrist flexors and extensors

- Grades I andII Maitland mobilization for intercarpals, inter-metacarpals, and metacarpophalangeal joints to restore the joint mobility and reduce stiffness

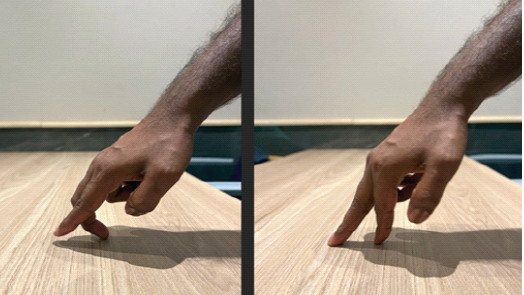

- Towel crumpling (Fig. 1), finger walking exercises for functional mobility of the hand (Fig. 2)

Figure 1: Towel crumpling exercise.

Figure 2: Finger walking exercise.

- Muscle energy technique to increase ROM at the wrist joint

- Mild stretching of the forearm flexor and extensor muscles to maintain muscle flexibilityand stretching of the hand muscles to prevent intrinsic muscle tightness

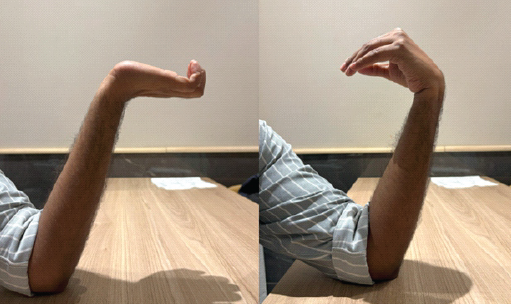

- Pain-free active-assisted ROM and active ROM for wrist and hand (Fig. 3)

Figure 3: Wrist and hand range of motion exercise.

- Tenodesis exercise (Fig. 4)

Figure 4: Tenodesis exercise.

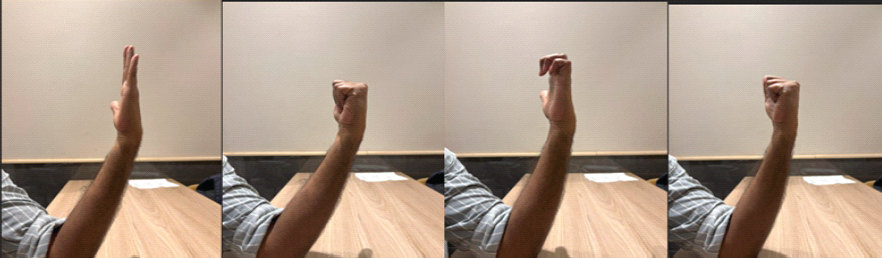

- Differential tendon gliding exercises for functional mobility and gripping activity (Fig. 5)

Figure 5: Differential tendon gliding.

- Proprioceptive training with the vestibular ball for improving motor control and joint compression on the upper extremity (Fig. 6)

Figure 6: Proprioceptive training using a vestibular ball.

- Begin mild resistance exercises with flex bar, thera-putty,therabands, or light weights at the end of 8 weeks (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Resistance training using flex bar, dumbbell, and thera-putty.

Adjuncts:

- Surged the faradic current to reduce pain and stimulate voluntary muscle contraction

- Electrical muscle stimulation to prevent muscle atrophy (Fig. 8)

Figure 8: Electrical muscle stimulation.

- Low-level laser therapy to relieve pain and aid fracture healing. It has shown to promote angiogenesis, bone healing, and stem cell osteogenic differentiation [7,8]

Phase III: Return to activity phase (9–12 weeks)

Goals of Rehabilitation:

- To achieve full ROM at the wrist joint

- To improve wrist and hand muscle flexibility

- To increase muscle strength and endurance around the wrist and forearm

- To improve proprioception at the wrist joint

- To improve hand grips, pinches, and prehension

- To promote return to functional activities

Bracing: No Bracing

Interventions:

Continue phase I and phase II exercises as per patient goals

- Active ROM for the wrist and hand

- Stretching of the wrist flexors and extensors, forearm muscles, biceps brachii, triceps brachii

- Grade III and IV mobilizations to radiocarpal, intercarpal, and metacarpophalangeal joints of the hand to increase joint play

- Quadrupod position for upper extremity weight-bearing and proprioception (Fig. 9)

Figure 9: Quadruped position for weight bearing on the hand and proprioceptive training.

- Balance training for the upper extremity using a BOSU ball (Fig. 10)

Figure 10: Proprioceptive training using a BOSUball.

- Elbow, forearm, wrist muscle strengthening using therabands and weights

- Finger strengthening using rubber bands, finger web

- Pegboard activities for improving fine motor activity

Adjuncts:

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) to maintain muscle property

- Extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) to accelerate bone healing. It has been used in cases of delayed union and malunion of fractures by bone remodeling and tissue regeneration through mechanical forces [9,10].

- Matrix rhythm therapy to relieve muscle spasm and regain muscle function. It aids in recovery after the fracture management through its action on the soft tissue [11,12].

Advanced strengthening phase (≥12 weeks)

Goals of rehabilitation:

- To return to the pre-injury level of wrist ROM and strength

- To achieve the optimal length-tension relation of the forearm and hand muscles

- To increase upper extremity strength

- To improve upper extremity proprioception and balance

- Skill-specific training.

Bracing: No Bracing

Interventions:

- Sports-specific strengthening of the upper extremity using therabands, weights, and isokinetic dynamometer

- Swimming for improving aerobic capacity and upper extremity strength training

- Plyometric training bilateral to unilateral upper extremity. It helps in increasing peak force generation andimproves muscle activation at peak performance [13]

- Battling ropes, punching, and throwing for upper extremity strength training.

Adjuncts:

- Isokinetic dynamometer for upper extremity strength training

- Blood flow restriction training for upper extremity power training

- ESWT to accelerate bone healing.

Rehabilitation in a DER fracture managed surgically using K-wire

Phase I: Immediate post-operative phase (0–4 weeks)

Goals:

- To counsel the patient about the fracture fixation and its rehabilitation for functional recovery

- To relieve pain and minimize swelling post fixation and immobilization

- To prevent muscular atrophy at forearm and hand

- To improve the wrist, forearm, and hand ROM

- To prevent immediate post-operative complications like compartment syndrome or a nerve injury

- Increase upper extremity and grip strength

- To maintain upper extremity function and scapular stability

- To improve aerobic capacity.

Weight-bearing status: Non-weight-bearing on the affected upper extremity

Exercise intervention:

- Immobilization in post-surgical cast for 2 weeks to prevent fracture re-displacement

- Elevation of the upper extremity above heart level using pillows to reduce the wrist and hand swelling

- Diaphragmatic and segmental breathing exercises to maintain cardiorespiratory function

- Active ROM for the cervical spine, shoulder, and elbow

- Pain-free active-assisted ROM for wrist and hand for 2 weeks

- Light towel crumpling and finger walking within the pain-free limits

- Submaximal isometric contraction exercises for wrist flexor and extensor muscles after 2 weeks

- Shoulder and elbow strengthening using manual resistance or weight cuffs.

Adjuncts:

- Cryotherapy for 7–10 minto reduce pain and swelling

- NMES to maintain upper extremity muscle property

- Interferential current therapy (IFT) for muscle relaxation over forearm.

Phase II: Intermediate phase (5–8 weeks)

Goals:

- To increase wrist ROM

- To improve muscle strength and endurance around wrist and forearm

- To improve muscle performance including flexibility and strength

- To improve upper extremity proprioception and balance

- To improve grips, pinches and prehension focusing on gross and fine motor skills.

Weight-bearing status: Partial weight-bearing on the affected upper extremity

Exercise intervention:

- Begin with pain-free AROM for wrist and hand

- Elevation, if swelling persists

- Mild wrist and finger stretching to prevent intrinsic muscle tightness

- Mobilization grade I and II for inter-carpals, metacarpals, and metacarpophalangeal joints

- Grip strengthening using a sponge ball

- Wrist flexion and extension using flexibar

- Pinch meter for improving pinch strength

- Pegboard activities to improve fine motor activities.

Adjuncts:

- Cryo-compression unit for the upper extremity if distal swelling present

- Matrix rhythm therapy to relax the upper limb soft tissue

- ESWT for accelerating bone healing and callus formation

- Mirror therapy is a kind of biofeedback therapy that helps to improve body schema perception after the surgery and can be a preventive measure for CRPS[14,2].

Phase III: Return to activity/ function phase (>8 weeks)

Goals:

- To achieve full, pain-free wrist, elbow, forearm, and shoulder ROM

- To improve forearm and grip strength

- To increase forearm and hand muscle endurance for functional tasks

- To restore neuromuscular control for precision movements

- To enhance proprioception and dynamic stability of the upper extremity.

Weight-bearing status: Full weight-bearing on the affected upper extremity

Exercise intervention:

Progressive resistance exercises: ball squeezing activities, therabands, and light-weight dumbbells for forearm and wrist strengthening.

- Tendon gliding and tendon blocking exercises

- Dumbbell wrist curls for wrist strengthening

- Kettlebell holds for isometric strengthening

- Prone on the forearm and hands

- Wall pushup – Table pushup – floor pushup (progress as tolerated)

- Differential tendon gliding exercises help focus on various grips and tendon gliding.

Adjuncts:

- Isokinetic dynamometer for strength training of the upper extremity

- Blood flow restriction training for upper extremity strength training and prevent atrophy

- Aquatic therapy for strengthening.

Rehabilitation in a DER fracture managed surgically using volar locking plate

Phase I: Immediate post-operative phase (0–4 weeks)

Goals:

- Patient counseling about the fracture and its fixation. Certain precautions that need to be taken should be explained following the surgery

- To prevent immediate post-operative complications

- To prevent skin complications

- To minimize pain and swelling in the hand

- To prevent arthrogenic muscle inhibition

- To initiate wrist ROM

- To increase upper-limb strength

- Improve aerobic endurance.

Weight-bearing status: Non-weight-bearing on the affected upper extremity

Exercise intervention:

- Immobilization in post-surgical cast for 2 weeks

- Elevation of the arm using pillows to reduce the swelling

- AROM for cervical spine, shoulder, and elbow

- Pain-free PROM for wrist and hand after 2 weeks

- Diaphragmatic and segmental breathing exercises

- Submaximal isometric wrist flexors and extensors

- Shoulder and elbow strengthening using manual resistance.

Adjuncts:

- Cryotherapy for 7–10 minto reduce pain and swelling

- NMES[4]

- IFT.

Phase II: Intermediate phase (5–8 weeks)

Goals:

- To increase wrist and hand ROM

- To improve muscle strength and endurance around wrist and forearm

- To improve muscle flexibility

- To improve upper extremity proprioception and balance

- To improve grips, pinches, and prehension.

Weight-bearing status: Non-weight-bearing on the affected upper extremity

Exercise Intervention:

- Begin AAROM for wrist and hand after 4 weeks within the pain-free ROM

- Elevation, if distal swelling persists

- Wrist and Finger stretching to prevent intrinsic tightness

- Mobilization grade I and II for inter-carpals, metacarpals, metacarpophalangeal joints to improve the joint play

- Wrist and strengthening using hand dynamometer

- Pinch meter for improving pinch strength

- Pegboard activities to improve fine motor activities.

Adjuncts:

- Cryo-compression unit if swelling present

- Matrix rhythm therapy

- Functional electrical stimulation

- ESWT

- Mirror therapy.

Phase III: Return to activity/function phase (>8 weeks)

Goals:

- To achieve full, pain-free ROM at the wrist, elbow, and shoulder

- To improve grip strength and forearm endurance for functional tasks

- To restore neuromuscular control for precision movements

- To enhance proprioception and dynamic stability of the upper extremity.

Weight-bearing status: Partial to full weight-bearing on the affected upper extremity as per patient’s tolerance

Exercise intervention:

- Wrist and forearm curls using therabands

- Gripping exercises using putty, hand grippers, or tennis ball

- Tendon gliding exercise (Fig. 8)

- Lifting and carrying tasks with progressive overload

- Simulate Activities of daily living for functional training

- Fine motor coordination exercises like gripping, writing, and picking up small objects

- Rowing and battle ropes for endurance training

- Medicine ball throws for explosivity.

Adjuncts:

- Isokinetic dynamometer for strength training

- Blood Flow Restriction Training

- Aquatic therapy for strengthening.

Rehabilitation of the distal radius fracture is a structured, phase-based process irrespective of any treatment modality. Recent evidence has strongly supported early mobilization; Zhou et al have shown that patients who started rehabilitation within two weeks post-operatively demonstrate superior functional results compared to those receiving delayed intervention (15). Mehta et al. emphasized in their Clinical Practice Guidelines for 2024 that participants in exercise are always better than those who do not exercise, regardless of whether there is a structured standardized protocol. (16).

CRPS after DER is still a significant complication. Recent questionnaires report heterogeneity in management strategies among professionals and underline the need to consider prevention strategies, such as early mobilization, desensitization exercises, and mirror therapy, as an integral part of rehabilitation programs (17). According to Świta et al., symptoms of CRPS may remain hidden even in late recovery; thus, patients should be closely monitored during all periods of rehabilitation (18).

Outcome measures reported by the patient include the DASH and MHQ scales, which represent validated tools for the follow-up of recovery. Emerging studies indicate that patient-specific factors, including age, comorbidities, baseline pain levels, and psychosocial factors such as depression, are more predictive of outcomes than treatment modality or radiographic parameters. This finding supports the development of individualized rehabilitation protocols that address the patient as a whole rather than focusing solely on anatomical restoration.

Adjunctive therapeutic modalities discussed in this context, such as low-level laser therapy, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, and neuromuscular electrical stimulation, represent recent concepts based on growing evidence. However, the heterogeneity of rehabilitation protocols across studies and limited high-quality evidence for some interventions highlight the need for further research to optimize timing, frequency, and intensity of specific rehabilitation strategies.

DER fracture requires a structured, phase-wise rehabilitation approach to ensure optimal recovery, whether treated conservatively or surgically. Early rehabilitation focuses on pain control, edema reduction, and maintaining ROM in adjacent joints. As healing progresses, therapy targets functional mobility at the wrist, strength, and proprioception. Advanced techniques such asNMES, Laser therapy, Mirror therapy, and Virtual rehabilitation can enhance outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach with the surgeon, physical therapist, and pain physician plays an important role. Patient compliance also dictates the progress after DER fracture. With personalized and evidence-based rehabilitation plans, most patients can return to daily activities with minimal impairments.

Successful rehabilitation following DER fracture hinges on a multifactorial approach that extends beyond fracture management to include patient-specific variables. Advancing age is associated with diminished bone density, reduced physiological reserve, and slower recovery which can compromise rehabilitation outcomes. Gender differences, particularly in postmenopausal women with underlying osteoporosis, further influence healing potential and functional recovery. Moreover, comorbid conditions such as diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, and inflammatory joint disorders negatively impact tissue healing and neuromuscular performance, posing additional barrier to rehabilitation. Tailoring rehabilitation protocols to account for these factors is essential to optimize functional outcomes, promote early return to activity, and reduce long-term disability.

References

- 1. Corsino CB, Reeves RA, Sieg RN. Distal radius fractures. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK536916/ [Last accessed on 2025]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. MeijerHA, ObdeijnMC, vanLoon J, vanden Heuvel SB, vanden Brink LC, SchijvenMP, et al.Rehabilitation after distal radius fractures: Opportunities for improvement.J Wrist Surg2023;12:460-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. IkpezeTC, SmithHC, LeeDJ, ElfarJC. Distal radius fracture outcomes and rehabilitation.Geriatr Orthop Surg Rehabil2016;7:202-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. HandollHH, ElliottJ. Rehabilitation for distal radial fractures in adults.Cochrane Database Syst Rev2015;2015:CD003324. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. ZhouZ, LiX, WuX, WangX. Impact of early rehabilitation therapy on functional outcomes in patients post distal radius fracture surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis.BMC Musculoskelet Disord2024;25:198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. YangL, ZhanYF, ZhaiZJ, RuanH, LiHW. Mechanisms and parameters of cryotherapy intervention for early postoperative swelling following total knee arthroplasty: A scoping review.J Exp Orthop2025;12:e70197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. BerniM, BrancatoAM, TorrianiC, BinaV, AnnunziataS, CornellaE, et al.The role of low-level laser therapy in bone healing: Systematic review.Int J Mol Sci2023;24:7094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. SæbøH, NaterstadIF, JoensenJ, StausholmMB, BjordalJM. Pain and disability of conservatively treated distal radius fracture: A triple-blinded randomized placebo-controlled trial of photobiomodulation therapy.Photobiomodul Photomed Laser Surg2022;40:33-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. PetrisorB, LissonS, SpragueS. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy: A systematic review of its use in fracture management.Indian J Orthop2009;43:161-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. LvF, LiZ, JingY, SunL, LiZ, DuanH. The effects and underlying mechanism of extracorporeal shockwave therapy on fracture healing.Front Endocrinol (Lausanne)2023;14:1188297. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. BhakaneyPR, WadhokarOC, UpaseS. Matrix rhythm therapy as a novel clinical approach in the rehabilitation of surgically treated distal radius fracture: A single case study.Cureus2024;16:e54785. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Warutkar VB, Samal S, Zade RJ. Matrix rhythm therapy (MRT) along with conventional physiotherapy proves to be beneficial in a patient with post-operative knee stiffness in case of tibia-fibula fracture: A case report. Cureus 2023;15:e45384. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. DaviesG, RiemannBL, ManskeR. Current concepts of plyometric exercise.Int J Sports Phys Ther2015;10:760-86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. KotiukV, BurianovO, KostrubO, KhimionL, ZasadnyukI. The impact of mirror therapy on body schema perception in patients with complex regional pain syndrome after distal radius fractures.Br J Pain2019;13:35-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Zhou Z, Li X, Wu X, Wang X. Impact of early rehabilitation therapy on functional outcomes in patients post distal radius fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2024;25:198. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Mehta SP, Karagiannopoulos C, Pepin ME, Ballantyne BT, Michlovitz S, MacDermid J, Grewal R, Martin RL. Distal Radius Fracture Rehabilitation: Clinical Practice Guidelines Linked to the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health From the Academy of Orthopaedic Physical Therapy and Academy of Hand and Upper Extremity Physical Therapy of the American Physical Therapy Association. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2024;54(9):CPG1-CPG78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Wang AW, Lefaivre KA, Potter J, Sepehri A, Guy P, Broekhuyse H, Roffey DM, Stockton DJ. Complex regional pain syndrome after distal radius fracture: A survey of current practices. PLoS One. 2024;19(11):e0314307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Świta M, Szymonek P, Talarek K, Tomczyk-Warunek A, Turżańska K, Posturzyńska A, Winiarska-Mieczan A. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome after Distal Radius Fracture—Case Report and Mini Literature Review. J Clin Med. 2024;13(4):1122. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]